Refereed Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published by Society of Interdisciplinary Business Research, 2014, Volume 3 (3) Papers Published in This Proceedings Have Been Double-Blind Peer Reviewed

SIBR-RDINRRU 2014 CONFERENCE ON INTERDISCIPLINARY BUSINESS & ECONOMICS RESEARCH September 27th - 28th, 2014 Kimberley Hotel, Hong Kong "The Interdisciplinary Approach to Research, Practice and Learning" Conference Proceedings Volume 3 (2014), Issue 3 ISSN: 2223-5078 Published by Society of Interdisciplinary Business Research, 2014, Volume 3 (3) Papers published in this proceedings have been double-blind peer reviewed Table of Content Technological Capability as a Determinant of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Indian h14-007 Sub-Continents The Impact of Crude Oil Price on Islamic Stock Indices of Gulf Cooperation Council: A Comparative h14-008 Analysis The Impact of Crude Oil Price on Islamic Stock Indices of South East Asian (SEA) Countries: A h14-009 Comparative Analysis h14-010 Diversification in Crude Oil and Other Commodities: A Comparative Analysis h14-011 Manifested Bullying Behavior of Secondary Students in Selected Public Schools in Baguio City, Philippines h14-012 Financial Inclusion in India Commodification of Cultural Capital by the Global Capitalist Cultural Apparatus: A Case Study of h14-013 Identity Among Malaysian Chinese Youth h14-014 Situational Analysis of Urban Informal Settlers of Cebu City h14-015 Difable Market as a Business Opportunity for Disabilities People IT influenced CSR in De-stabalized Economy with Comparative Analysis of Various European h14-016 Countries Comparative Analysis of Metacognitive Strategies Used in the Internet-integrated Test to Enhance h14-017 English Speaking Ability in Thai Tourism Context -

Success Factors in Community-Based Tourism in Thailand: the Role of Luck, External Support, and Local Leadership

Tourism Planning & Development, Volume 11, Issue 1, February 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2013.852991 Success Factors in Community-Based Tourism in Thailand: The Role of Luck, External Support, and Local Leadership NICK KONTOGEORGOPOULOS*, ANUWAT CHURYEN** AND VARAPHORN DUANGSAENG** *International Political Economy Program, University of Puget Sound, 1500 North Warner, Tacoma, WA 98416, USA and **School of Tourism Development, Maejo University, 63 Moo 4, Chiang Mai - Phrao Road, Sansai, Chiang Mai 50290, Thailand ABSTRACT The dominant narrative regarding tourism in Thailand centers on the various negative social and environmental consequences of rapid growth, but in the midst of this explosive expansion of conventional tourism, a less recognized story has recently emerged. Due to the efforts of researchers, environmental activists, non-governmental organizations, and public officials, community-based tourism (CBT) has become in the past decade an important component of the domestic tourism market, and signifies trends that are more encouraging than those associated with more conventional forms of tourism in Thailand. While it is true that some rural communities in Thailand struggle to plan, initiate, and sustain CBT projects, it is nevertheless possible, with the right combination of circumstances, to pursue successful CBT. The paper explores the emergence of CBT in Thailand, and examines the case study of Mae Kampong, a village in the Northern Thai province of Chiang Mai that is renowned nationally as a showcase CBT community. Using data and observations gathered during more than 30 research or study-tour visits to Mae Kampong, this paper argues that fortunate geographical conditions, external support, and transformational leadership represent the most important determinants of success for CBT in Thailand. -

Excavations at Ban Tamyae and Non Ban Kham, Phimai Region, Northeast Thailand

Excavations at Ban Tamyae and Non Ban Kham, Phimai Region, Northeast Thailand Received October 1986, revised July 1989 DA VID J. WELCH AND J. R. MCNEILL INTRODUCTION DURING 1979 AND 1980 the Khorat Basin Archaeological Project (KBAP)-a co operative project involving researchers from the University of Hawaii, the Fine Arts Department of Thailand, and Chulalongkorn University-conducted survey and excavation of sites in the vicinity of the town of Phimai in northeast Thailand. Phimai formerly served as a regional Khmer sacred, administrative, and commerical center from about A.D. 1000 to 1300. Archaeological and historical evidence indi cated that Phimai might have been an important center before its integration into the Khmer state. The approach taken in the research was regional, investigating the development of Phimai as a major center by focusing upon the towns that formed alternative or minor centers and upon the villages and farms that constituted the hinterland for Phimai and supported its development. The primary focus of the investigations was on the fortified or moated sites, sites surrounded with earth walls and moats, first identified on aerial photographs by Peter Williams-Hunt (1950). The goals of the research included the location, mapping, and dating of the moated sites in the Phimai region and determination of the function, date of construction, and present condition of the earthworks at these sites. Two hypotheses were pro posed for testing: (1) the concentration of population into these moated sites was associated with the practice of intensive wet rice agriculture, and (2) these sites were centers for long-distance exchange. -

Relationship Between Soil Salinity and Chloride Content in Groundwater Within Saline Soil Areas

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOIL SALINITY AND CHLORIDE CONTENT IN GROUNDWATER IN SALINE SOIL AREAS OF NAKHON RATCHASIMA PROVINCE Wannida Thongwat A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil, Transportation and Geo-resources Suranaree University of Technology Academic Year 2018 ความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างความเค็มของดินกับปริมาณคลอไรด์ในน ้าบาดาลบริเวณ พื้นที่ดินเค็มของจังหวัดนครราชสีมา นางสาววรรณิดา ทองวัฒน์ วทิ ยานิพนธ์นเี้ ป็นส่วนหนงึ่ ของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรปริญญาวศิ วกรรมศาสตรมหาบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาวิศวกรรมโยธา ขนส่ง และทรัพยากรธรณี มหาวทิ ยาลยั เทคโนโลยสี ุรนารี ปีการศึกษา 2561 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the funding support from Suranaree University of Technology The author would like to express my deep gratitude to Assistant Professor Dr.Bantita Terakulsatit, my thesis advisors, for her valuable and constructive suggestions, patience, enthusiastic encouragement, and the continuous support of my study and research. I would also like to thank Assistant Professor Dr.Akkhapun Wannakomol, Dr. Tawisak Silakul and Mr.Sakchai Glumglomjit for their advice and guidance since the first day of this master's program. My grateful thanks are also extended to Mr.Saroot Lualon and Miss Orawan Srihabuntan, for their help in doing the data analysis, and to Mr.Thanakorn Thongwat and Miss Warunya Nuchnoi, for their support in the site measurement. I would also like to extend my thanks to the technicians of the laboratory for their help in offering me the resources in running the program. -

SALT RESERVE ESTIMATION for SOLUTION MINING in the KHORAT BASIN Hathaichanok Vattanasak

SALT RESERVE ESTIMATION FOR SOLUTION MINING IN THE KHORAT BASIN Hathaichanok Vattanasak A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Geotechnology Suranaree University of Technology Academic Year 2006 กกกก ก ก กกกก กก 2549 SALT RESERVE ESTIMATION FOR SOLUTION MINING IN THE KHORAT BASIN Suranaree University of Technology has approved this thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master’s Degree. Thesis Examining Committee _______________________________ (Asst. Prof. Thara Lekuthai) Chairperson _______________________________ (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kittitep Fuenkajorn) Member (Thesis Advisor) _______________________________ (Assoc. Prof. Ladda Wannakao) Member _________________________________ _________________________________ (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Saowanee Rattanaphani) (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Vorapot Khompis) Vice Rector for Academic Affairs Dean of Institute of Engineering ก ก : กกกก (SALT RESERVE ESTIMATION FOR SOLUTION MINING IN THE KHORAT BASIN) ก : . ก , 191 . กกก กกกก 1) - ก 2) กกกกกก 3) กกกกกกกกก 4) กกกกกก 5) กกก กกกก 100 -700 กก ก 1 1,000 กกกก กกกกก 60 ก 150 ก 140 340 60 30 (กกกกก) ก 240 กก กก 50 ก ก 2.92 กก ก 6.45 กกก กกกกก กกก ก ก กกก ก 2 กก 201,901 กก 97% กก กก 35,060 กก 7,329 กก ______________________ กก 2549 ก ________________ HATHAICHANOK VATTANASAK : SALT RESERVE ESTIMATION FOR SOLUTION MINING IN THE KHORAT BASIN. THESIS ADVISOR : ASSOC. PROF. KITTITEP FUENKAJORN, Ph.D., P.E. 191 PP. SALT/RESERVE/KHORAT BASIN/SOLUTION -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ........................... -

Community - Based Tourism Management of Ban Prasat, Non Sung District, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand

Community - Based Tourism Management of Ban Prasat, Non Sung District, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand Suchada Nguangchaiyapoom 1 Sekson Yongvanit 2 Mattara Sripun 3 Abstract Tourism has long been recognized for its major contribution to Thailand’s economic growth. The country has continuously promoted the tourism sector for over 30 years, undertaking numerous campaigns and strategies to foster the development of tourism. More recently, efforts have been emphasizing on tourism development at the community level in which tourism is increasingly being recognized for its socio-economic benefits to the host communities. Community-Based Tourism (CBT) is the approach that recognizes the social, environmental and economic impacts of tourism upon the local community and its surroundings. CBT focuses on the involvement of local community in the development process and ensures that a major share of tourism benefits remains within the community. The main purpose of this paper is to examine the development of CBT at Ban Prasat village archaeological site in Thailand, with a specific focus on its local management practices. Specifically, the paper outlines three main themes. The first is to examine the development of CBT in the village and 1 Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Khon Kaen University, Thailand 2 Associate Professor Dr. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Khon Kaen University, Thailand 3 Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Khon Kaen University, Thailand Community - Based Tourism Management of Ban Prasat, Non Sung District, 192 Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) promotional and training programs, followed by a brief synopsis of three different periods of the development. -

Rajabhat J. Sci. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Xx(X)

Rajabhat J. Sci. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 19(1): 119-130, 2018 การออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรม: อุโบสถฐานโค้งท้องส าเภาในจังหวัดนครราชสีมา ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN: CURVE OF THE BOTTOM BASE SHIP-SHAPED UBOSOT IN NAKHON RATCHASIMA กาญจนา ตันสุวรรณรัตน์* และปริญญา แก้วมีค่า Kanjana Tansuwanrat*, and Prinya Kaewmeekha *Faculty of Fine Art and Industrial Design, Rajamangala University of Technology Isan *corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] บทคัดย่อ งานวิจัยการออกแบบสถาปัตยกรรม: อุโบสถฐานโค้งท้องส าเภาในจังหวัดนครราชสีมา มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อศึกษาแนวความคิดในการออกแบบและศึกษารูปแบบทางสถาปัตยกรรม อุโบสถฐาน โค้งท้องส าเภาในจังหวัดนครราชสีมา โดยศึกษาแนวความคิดในการออกแบบอุโบสถสมัยอยุธยาตอน ปลายถึงรัตนโกสินทร์ตอนต้น และส ารวจอุโบสถฐานโค้งท้องส าเภาในจังหวัดนครราชสีมา ซึ่งมีอายุ อาคารระหว่างสมัยอยุธยาตอนปลายถึงรัตนโกสินทร์ตอนต้น พบอุโบสถที่มีสภาพสมบูรณ์สามารถเก็บ ข้อมูลด้วยการส ารวจรังวัด จ านวน 2 หลัง คือ พระอุโบสถวัดบึง (พระอารามหลวง) อ าเภอเมือง และ อุโบสถวัดหน้าพระธาตุ อ าเภอปักธงชัย พบว่า แนวความคิดในการออกแบบอุโบสถฐานโค้งท้องส าเภา เป็นการเชื่อมโยงนามธรรมไปสู่รูปธรรมได้อย่างงดงาม โดยน าหลักธรรมในพระพุทธศาสนาเรื่อง เวสสันดรชาดกซึ่งเป็นพระชาติที่ยิ่งด้วยมหาทานบารมี จากการเทศน์มหาชาติกัณฑ์กุมารซึ่งกล่าวถึงการ สละบุตรธิดาอันเป็นประดุจแก้วตาดวงใจของบิดา ท าให้พุทธศาสนิกชนได้รับรู้ถึงความส าคัญของการ สร้างบารมี เป็นอริยทรัพย์ดุจดังส าเภาแก้วที่พาข้ามห้วงแห่งวัฏสงสาร รูปธรรมของอุโบสถฐานโค้งท้อง ส าเภาจึงบ่งบอกถึงพุทธนาวาที่จะน าพาสรรพสัตว์ทั้งหลายฝ่ากระแสคลื่นลมของกิเลสข้ามถึงฝั่งพระ นิพพานซึ่งเป็นที่ปรารถนาของพุทธศาสนิกชน รูปแบบพระอุโบสถวัดบึง ได้รับอิทธิพลของอยุธยาตอน -

Facility Location Problem

การพฒั นาตวั แบบการจดั สรรตา แหน่งของหน่วยการแพทย์ฉุกเฉิน เพอื่ ลดระยะเวลาการเข้าถงึ จุดเกดิ เหตุ กรณีศึกษาจังหวัดนครราชสีมา นายวโรรส อินทรศิริพงษ์ วทิ ยานิพนธ์นีเ้ ป็ นส่วนหนึ่งของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรปริญญาวศิ วกรรมศาสตรมหาบัณฑิต สาขาวชิ าวศิ วกรรมอุตสาหการ มหาวทิ ยาลัยเทคโนโลยสี ุรนารี ปีการศึกษา 2557 THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN EMS FACILITY LOCATION MODEL TO MINIMIZE RESPONSE TIME : A CASE STUDY OF NAKHON RATCHASIMA ROVINCE Waroros Intarasiripong A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Industrial Engineering Suranaree University of Technology Academic Year 2014 การพฒั นาตัวแบบการจัดสรรต าแหน่งของหน่วยการแพทย์ฉุกเฉิน เพอื่ ลดระยะเวลาการเข้าถึงจุดเกดิ เหตุ กรณีศึกษาจังหวัดนครราชสีมา (ตัวอักษรเข้มขนาด 18) มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีสุรนารี อนุมตั ิให้นบั วิทยานิพนธ์ฉบบั น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษา ตามหลักสูตรปริญญามหาบัณฑิต คณะกรรมการสอบวิทยานิพนธ์ ____________________________ (รศ. ดร.พรศิริ จงกล) ประธานกรรมการ ____________________________ (ผศ. ดร.พงษ์ชัย จิตตะมัย) กรรมการ (อาจารย์ที่ปรึกษาวิทยานิพนธ์) ____________________________ (ผศ. ดร.ปภากร พิทยชวาล) กรรมการ ____________________________ ____________________________ (ศ. ดร.ชูกิจ ลิมปิจานง ค์) (รศ. ร.อ. ดร.กนต์ธร ชานิประศาสน์ ) รองอธิการบดีฝ่ายวิชาการและนวัตกรรม คณบดีสานักวิชาวิศวกรรมศาสตร์ วโรรส อินทรศิริพงษ์ : การพฒั นาตวั แบบการจดั สรรตา แหน่งของหน่วยการแพทย ์ ฉุกเฉินเพื่อลดระยะเวลาการเขา้ ถึงจุดเกิดเหตุ กรณีศึกษาจังหวัดนครราชสีมา (THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN EMS FACILITY LOCATION MODEL TO MINIMIZE RESPONSE TIME : A CASE STUDY OF NAKHON -

Leadership Entrepreneurial En Communauté Pour Une Performance Durable : Études De Cas Dans Le Tourisme À Base Communautaire Homestay, En Thailande Netdao Chaiyakhet

Leadership entrepreneurial en communauté pour une performance durable : études de cas dans le tourisme à base communautaire Homestay, en Thailande Netdao Chaiyakhet To cite this version: Netdao Chaiyakhet. Leadership entrepreneurial en communauté pour une performance durable : études de cas dans le tourisme à base communautaire Homestay, en Thailande. Gestion et man- agement. Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III, 2014. Français. NNT : 2014MON30022. tel- 01084751 HAL Id: tel-01084751 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01084751 Submitted on 20 Nov 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ! ! ! Délivré par ETABLISSEMENT Préparée au sein de l’école doctorale 60 TTST- TERRITOIRES, TEMPS, SOCIÉTES ET DÉVELOPPEMENT Et de l’unité de recherche MRM - MONTPELLIER RECHERCHE EN MANAGEMENT Spécialité : Sciences de Gestion Présentée par CHAIYAKHET Netdao Leadership entrepreneurial en communauté pour une performance durable: études de cas dans le tourisme à base communautaire Homestay Soutenue le 18 Juillet 2014 devant le jury composé de M. Alain BRIOLE, Professeur, Université Paul President Valéry Montpellier III M. Jean-Paul TCHANKAM, Professeur HDR, Rapporteur Bordeaux Ecole de Management M. Laurent CAPPELLETTI, Professeur, Ecole Rapporteur Management & Société du CNAM, Paris M. Jean-Michel PLANE, Professeur, Directeur de Th ése Université Paul Valéry Montpellier III ! TITRE EN FRANÇAIS: Leadership entrepreneurial en communauté pour une performance durable: études de cas dans le tourisme à base communautaire Homestay, en Thaïlande. -

Ginglymodian Fishes (Actinopterygii, Holostei) from Thailand: an Overview

Original Ginglymodian fi shes (Actinopterygii, Holostei) from Thailand: An overview Lionel Cavin1*, Uthumporn Deesri2,3, Varavudh Suteethorn2 Received: 30 July 2013; Accepted: 15 October 2013 Abstract Isolated ganoid fi sh scales are not uncommon in Mesozoic deposits of Thailand. Traditionally referred to ‘semionotiform’ or Lepidotes-like fi shes, they were not assigned to well-defi ned taxa and are of little use for palaeontological reconstructions. During the last fi fteen years, however, the discovery of well-preserved articulated fi sh specimens, with ganoid squamations, allowed us to properly defi ne new taxa, to search for phylogenetic relationships and to address the place of these fi shes in palaeoenvironments. So far two genera and three species of ginglymodians have been named on the basis on material from the Phu Kradung Formation, but at least nine different taxa have been recognized ranging from the Late Triassic to the Aptian. Phylogenetic analyses of Thaiichthys and Isanichthys indicate that they belong, or are closely related, to the Lepisosteiformes. The palaeogeographical distribution of the four known Isanichthys species is restricted to the northern margin of the Tethys during the Middle Jurassic to the basal Cretaceous. The palaeobiogeographical signal of Thaiichthys is more ambiguous, its closest relatives having been found in the early Late Cretaceous of western Gondwana (South America and Africa). Keywords: Cretaceous, Ginglymodi, palaeobiogeography, phylogeny Introduction articulated material, in particular if no articulated cranial Mesozoic deposits worldwide, both marine and freshwater material is preserved. Relatively complete specimens in in origin, have yielded isolated ganoid scales commonly anatomical connexion of ginglymodians, however, are referred to ‘semionotiforms’ or Lepidotes-like fi shes. -

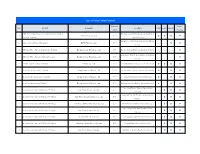

List of Solar Power Projects Capacity Public No

List of Solar Power Projects Capacity Public No. Project Company Location COP ESA IEE-SD (MW) Hearing 5 MW Photovoltaic Power Generation Project at Saraburi Tha Maprang Sub District, Kaeng Khoi District, 1 Infinite Green Co.,Ltd. 5.00 l l l l province, Thailand Saraburi Province Bang Pa-in District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya 2 Bangchak Solar Farm at Bangpa-In BCPG Public Co., Ltd. 38.00 - - l l Province 3 BSE Solar Power Plant at Chaiyaphum, Thailand Bangchak Solar Energy Co., Ltd. 8.00 Bamnet Narong District, Chaiyaphum Province - - - l Bang Pahan District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya 4 BSE Solar Power Plant at Ayutthaya,Thailand Bangchak Solar Energy Co., Ltd. 8.00 - - - l Province 5 EA Solar Farm at Lopburi, Thailand EA Solar Co., Ltd. 8.00 Phatthana Nikhom District, Lopburi Province l l l l 6 Solar Farm at Phitsanulok, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Phrom Phiram District, Phitsanulok Province l - l l 7 Solar Farm at Nakhonsawan, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Takhli District, Nakhon Sawan Province l - l l 8 Solar Farm at Lampang, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Mueang Lampang District, Lampang Province l - l l Non Sung District, Nakhon Ratchasima 9 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Korat 1) Co.,Ltd. 6.00 - l l l Province Sawang Daen Din District, Sakon Nakhon 10 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Sakon Nakhon 1) Co.,Ltd. 6.00 - l l l Province 11 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Nakhon Phanom 1) Co.,Ltd.