Beyond Resource Mobilization Theory: Dynamic Paradigm of Chengara Struggle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

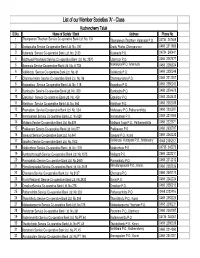

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 28.03.2021To03.04.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 28.03.2021to03.04.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PUTHENPURAKK PATHANA Shaiju si of AL HOUSE 03-04-2021 449/2021 U/s 59, MTHITTA police BAILED BY 1 JAMES P G GEORGE P T CHENGARA PO Vettoor at 20:45 279 IPC & 185 Male (Pathanamth Pathanamthitt POLICE PATHANAMTHITT Hrs MV ACT itta) a A 444/2021 U/s PATHANA Akhil bhavanam 03-04-2021 Ramesh 23, Central 279 IPC MTHITTA BAILED BY 2 Akhil Saji puthussery bhagam at 09:30 kumar, SI of Male junction PTA 3(1)r/w 181 (Pathanamth POLICE village vayalar pta Hrs Police MV act itta) palanilkunnathil PATHANA house eramuriyil 02-04-2021 443/2021 U/s Philip 29, central MTHITTA sanju joseph BAILED BY 3 jonin skariya ,chengara at 15:40 118(a) of KP mathue Male jungtion (Pathanamth SI of Police POLICE malayalapuzha po Hrs Act itta) pta ph: 9072903892 Lekshmi nivas PATHANA MUNDUKOTTACK 02-04-2021 SASIKUMA 32, 442/2021 U/s MTHITTA Rejimon, SI of BAILED BY 4 PRASANTH AL PO Aban junction at 15:39 R Male 279 IPC (Pathanamth Police POLICE PATHANAMTHITT Hrs itta) A 9447555794 PATHANA Kalleckal kavumkal 01-04-2021 441/2021 U/s Narayanan 51, College MTHITTA Sunny k SI of BAILED BY 5 Ajayakumar Imali Omaloor po at 22:20 279 IPC & 185 nair Male junction pta (Pathanamth Police POLICE Pathanamthitta Hrs MV ACT itta) -

(Rs.) DATE of TRANSFER to IEPF BALASUBRAMANIAN

NAME OF ENTITLED SHAREHOLDER LAST KNOWN ADDRESS NATURE OF AMOUNT ENTITLED DATE OF TRANSFER AMOUNT (Rs.) TO IEPF BALASUBRAMANIAN M Snuvy Coop Hsg Soc Ltd Plot No 29 Sector-2 Flat No 10 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 Koperkhai Lane New Mumbai 400701 SBT for FY 2003-2004 VAISHALI PORE Clerk/typist 125 M G Road N M Wadia Bldg Fort Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 Mumbai Mumbai 400023 SBT for FY 2003-2004 VINOD MENON Sbi Capital Markets Ltd 202 Maker Tower `e' Cuffe Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 Parade Mumbai Mumbai 400005 SBT for FY 2003-2004 GAUTAM KAUSHAL KUMAR Cl/ca S B T 125 M G Road Fort Mumbai Mumbai Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 400023 SBT for FY 2003-2004 KANAKARAJ P Sbt Chennai Main 600108 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 PREMALATHA MANONMANI Sbt Mount Road Madras 600002 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 1500.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 SUBRAMANIAN E N Sbt Mount Road Madras 600002 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 PRABU K Sbt Mount Road Madras 600002 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 RAGUNATHAN S 28 Jesurathinam St C S I School Comp Sulur 641402 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 MOHAMMEDALI M 4a Sabeena St New Ellis Nagar Madurai 625010 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 375.00 14-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2003-2004 VISVANATHAN Periyavila House Arudison Village St Mangad P O K K Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 750.00 14-Jan-2021 Dist 679001 SBT for FY 2003-2004 PUGALENDI R Plot No. -

SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014

1 St. Thomas College KOZHENCHERRY, KERALA STATE- 689 641 Phone: 0468-2214 566 Fax: 0468-2215 543 Website: www.stthomascollege.info E-mail: [email protected] (Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University) Re-accredited by NAAC with B++ (2007) SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council Bangalore -560 072, India NAAC-SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014 5 PREFACE he Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church, a staunch ally of an epoch- T making social movement of the nineteenth century, was led forward by the lamp of Reformation popularly known as „Naveekarana Prasthanam‟. Mar Thoma Church, part of the great tradition of the Malankara Syrian Church which had been formulated by St. Thomas, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ, wielded education during the progressive period of Reformation in Kerala, as a mighty weapon for the liberation of the downtrodden masses from their stigmatized ignorance and backwardness. The establishment of St.Thomas College at Kozhencherry in 1953, as part of the altruistic missionary zeal of the church during Reformation, was the second educational venture under the auspices of Mar Thoma Church. The founding fathers, late Most Rev. Dr. Juhanon Mar Thoma Metropolitan and late Rev. K.T.Thomas Kurumthottickal, envisaged the college as an instrument for the realization of a bold vision that aimed at providing quality education to the people of the remote hilly regions of Eastern Kerala. The last six decades of the momentous historical span of the college has borne witness to the successful fulfilment of the vision of the founding fathers. The college has gone further into newer dimensions, innovations and endeavours which are impactful and relevant to the shaping of the lives of contemporary and future generations of youngsters. -

11.04 Hrs LIST of MEMBERS ELECTED to LOK SABHA Sl. No

Title: A list of Members elected to 14th Lok Sabha was laid on the Table of the House. 11.04 hrs LIST OF MEMBERS ELECTED TO LOK SABHA MR. SPEAKER: Now I would request the Secretary-General to lay on the Table a list (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of the Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. SECRETARY-GENERAL: Sir, I beg to lay on the Table a List* (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. List of Members Elected to the 14th Lok Sabha. * Also placed in the Library. See No. L.T. /2004 SCHEDULE Sl. No. and Name of Name of the Party Affiliation Parliamentary Constituency Elected Member (if any) 1. ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SRIKAKULAM YERRANNAIDU KINJARAPUR TELUGU DESAM 2. PARVATHIPURAM(ST) KISHORE CHANDRA INDIAN NATIONAL SURYANARAYANA DEO CONGRESS VYRICHERLA 3. BOBBILI KONDAPALLIPYDITHALLI TELEGU DESAM NAIDU 4. VISAKHAPATNAM JANARDHANA REDDY INDIAN NATIONAL NEDURUMALLI CONGRESS 5. BHADRACHALAM(ST) MIDIYAM BABU RAO COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 6. ANAKAPALLI CHALAPATHIRAO PAPPALA TELUGU DESAM 7. KAKINADA MALLIPUDI MANGAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL PALLAM RAJU CONGRESS 8. RAJAHMUNDRY ARUNA KUMAR VUNDAVALLI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 9. AMALAPURAM (SC) G.V. HARSHA KUMAR INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 10. NARASAPUR CHEGONDI VENKATA INDIAN NATIONAL HARIRAMA JOGAIAH CONGRESS 11. ELURU KAVURU SAMBA SIVA RAO INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 12. MACHILIPATNAM BADIGA RAMAKRISHNA INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 13. VIJYAWADA RAJAGOPAL GAGADAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14. -

The Struggle in Chengara

the struggle in chengara L The year old Chengara struggle is a movement by landless Dalits, Adivasis and other marginalised peoples for land in the southern plantation belt of Pathanamthitta, Kerala. It is a fight- to rnaKe the Government fulfil its promise. To this end, about 5000 families totalling around 30,000 people from different parts of the region have moved on to the Harrison Malayalam F'rivate Ltd estate. The tease of Harrison Malayalam Ltd expired in 1985 and no rents have been paid to the State exchequer since. The struggle is also against illegal encroachment by a corporation. The Chengara Land struggle exposes the inadequacies of land reforms in Kerala that were effected in 197b. The three main inadequacies ~f the ,. --3s are: Onc, ,p plantations were untouched, and that meant that the landlessness of the plantation workers was overlooked. Two, the refonns on rice fields and garden lands transferred land to intermediate and small tenants but excluded landless labourers belonging mostly to socially disadvantaged castes and communities. Three, the amount of land redistributed was very small. In fact the 25,000 hectares with Harrison Malayalam Ltd is larger than the total land distributed in the whole of Keralal Furthermore, the Chengara struggle demonstrates that identities of caste and tribe are as important as class is. The CPI (M), currently in power in Kerala and the state machinery have come down heavily on the protesters. They have been brutally beaten, women raped and assaulted, and food and supplies have been prevented from reaching the people by CPI (M) cadre who surrounded the area. -

Fairs and Festivals of Kerala-Statements, Part VII B (Ii

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME VII KERALA PART VII B (ii) FAIRS AND FESTIVALS OF KERALA-STATEMENTS M. K. DEVASSY~ B. A., B. L. OF TbE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent ql Census Operations, KeTola and the Union Territory of Laccadive, Minicoy and Amindivi Islands PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS. DELHI-8 PRINTED AT THB C. M. S. PRESS. KOTfAYAM 1968 PRICE: Delux.e Rs. 20.00 or 46 sh. 8 d. or $ 7.20 cents Ordinary Rs.8.75 or 20 sh. 5 d. or $ 3.15 cents PREFACE It is one of the unique features of the 1961 Cell3us that a comprehensive survey was conducted about the fairs and festivals of the country. Apart from the fact that it is the first systematic attempt as far as Kerala is concerned, its particular value lay in presenting a record of these rapidly vanishing cultural heritage. The Census report on fairs and festivals consists of two publications, Part VII B (i), Fairs and Festivals of Kerala containing the descriptive portion and Part VII B (ii), Fairs and Festivals of Kerala-Statements giving the tables relating to the fairs and festivals. The first part has already been published in 1966. It is the second part that is presented in this book. This publication is entirely a compilation of the statements furnished by various agencies like the Departments of Health Services, Police, Local Bodies, Revenue and the Devaswom Boards of Travancore and Cochin. This is something like a directory of fairs and festivals in the State arranged according to di'>tricts and taluks, which might excite the curiosity of the scholars who are interested in investigating the religiou, centres and festivals. -

A Reassessment of Power and Social Development in Kerala, India

Capability and Cultural Subjects – A Reassessment of Power and Social Development in Kerala, India By Tamara Nair A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities, University of New South Wales 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Nair First name: Tamara Other name/s: - Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: School of Humanities Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: Capability and Cultural Subjects – A Reassessment of Power and Social Development in Kerala, India Abstract This thesis explores connections between power and social development through an examination of capabilities and the formation of cultural subjects in tribal and fishing communities in the state of Kerala, India. Kerala has long been studied for its unique development model and, since 1996, its People's Plan for Democratic Decentralisation. Although Kerala is not exclusive in pursuing decentralised planning, its successes make it stand out from other Indian states and even other parts of the developing world. Despite its achievements, several scholars question Kerala's development outcomes including the continued deprivation faced by tribal and fishing communities. Through analysing the disadvantages faced by these communities utilising Amartya Sen's capability approach and Michel Foucault's concepts of power and subject creation, this thesis hopes to contribute to a reassessment of social development in Kerala. By illuminating factors besides income that signify development, and acknowledging cultural contexts that affect the participation of marginalised communities in development planning and decision- making, the thesis proposes ways in which these communities can be empowered while also exploring barriers to this empowerment. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 13.09.2020To19.09.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 13.09.2020to19.09.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SHANTHALAYAM SREEJITH B.S VEEDU, 19-09-2020 ADOOR 43, 2502/2020 SI OF ARRESTED - 1 BINOY VIJAYAN MELLUDU, ADOOR PS at 22:37 (Pathanamth Male U/s 308 IPC POLICE JFMC Adoor PERINGANADU, Hrs itta) ADOOR ADOOR BIJU MANSIL, 2501/2020 EZHAMKULAM SREEJITH B.S MOYTHIN 19-09-2020 U/s ADOOR 61, VILLAGE, MAUTHIMO SI OF BAILED BY 2 SALIM KANNU at 18:00 447,427,153 (Pathanamth Male NEDUMAN , ODU POLICE POLICE RAWUTHER Hrs IPC & 11(A) itta) PATTAZHI ADOOR & KP ACT MUKKU, ADOOR PERUMKOMBIN, 2500/2020 SREEJITH B.S KARUVAYAL, 19-09-2020 ADOOR PRASHANT 20, PLATATION U/s 279 IPC SI OF BAILED BY 3 PRAKASH KALANJOOR, at 14:35 (Pathanamth H Male JN & 3(1) r/w POLICE POLICE ENADIMANGALA Hrs itta) 181 MV Act ADOOR M, ADOOR KOCHU VEEDU, 2499/2020 KARUNAGAPALL U/s 269, 270 Y, IPC & Sec. SREEJITH B.S PANIKRYAKADAV 19-09-2020 4(2)(h) r/w 5 ADOOR THAMARA 30, ADOOR HS SI OF BAILED BY 4 SANEESH E, at 12:35 of Kerala (Pathanamth KSHAN Male JN POLICE POLICE AYANIVELIKULA Hrs Epidemic itta) ADOOR NGARA, Diseases KARUNAGAPALL Ordinance Y 2020 BHASKARA 2499/2020 VILASAM, KATTIL U/s 269, 270 KADAVU, IPC & Sec.