A Reassessment of Power and Social Development in Kerala, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project

Athirapally Hydel Electric Project drishtiias.com/printpdf/athirapally-hydel-electric-project Why in News Recently, the Kerala government has approved the proposed Athirapally Hydro Electric Project (AHEP) on the Chalakudy river in Thrissur district of the state. There are already five dams for power and one for irrigation and it will be the seventh along the 145 km course of the Chalakudy river. Chalakudy River It originates in the Anamalai region of Tamil Nadu and is joined by its major tributaries Parambikulam, Kuriyarkutti, Sholayar, Karapara and Anakayam in Kerala. The river flows through Palakkad, Thrissur and Ernakulam districts of Kerala. It is the 4th longest river in Kerala and one of very few rivers of Kerala, which is having relics of riparian vegetation in substantial level. A riparian zone is the interface between land and a river or stream. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks are called riparian vegetation, characterized by hydrophilic plants. It is the richest river in fish diversity perhaps in India as it contains 85 species of freshwater fishes out of the 152 species known from Kerala only. The famous waterfalls, Athirappilly Falls and Vazhachal Falls, are situated on this river. It merges with the Periyar River near Puthenvelikkara in Ernakulam district. Key Points 1/3 The total installed capacity of AHEP is 163 MW and the project is supposed to make use of the tail end water coming out of the existing Poringalkuthu Hydro Electric Project that is constructed across the Chalakudy river. AHEP envisages diverting water from the Poringalkuthu project as well as from its own catchment of 26 sq km. -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

Unclaimed September 2018

SL NO ACCOUNT HOLDER NAME ADDRESS LINE 1 ADDRESS LINE 2 CITY NAME 1 RAMACHANDRAN NAIR C S/O VAYYOKKIL KAKKUR KAKKUR KAKKUR 2 THE LIQUIDATOR S/O KOYILANDY AUTORIKSHA DRIVERS CO-OP SOCIE KOLLAM KOYILANDY KOYILANDY 3 ACHAYI P K D/OGEORGE P K PADANNA ARAYIDATH PALAM PUTHIYARA CALICUT 4 THAMU K S/O G.R.S.MAVOOR MAVOOR MAVOOR KOZHIKODE 5 PRAMOD O K S/OBALAKRISHNAN NAIR OZHAKKARI KANDY HOUSE THIRUVALLUR THIRUVALLUR KOZHIKODE 6 VANITHA PRABHA E S/O EDAKKOTH HOUSE PANTHEERANKAVU PANTHEERANKAVU PANTHEERAN 7 PRADEEPAN K K S/O KOTTAKKUNNUMMAL HOUSE MEPPAYUR MEPPAYUR KOZHIKODE 8 SHAMEER P S/O KALTHUKANDI CHELEMBRA PULLIPARAMBA MALAPPURAM 9 MOHAMMED KOYA K V S/O KATTILAVALAPPIL KEERADATHU PARAMBU KEERADATHU PARAMBU OTHERS 10 SALU AUGUSTINE S/O KULATHNGAL KOODATHAI BAZAR THAMARASSERY THAMARASSE 11 GIRIJA NAIR W/OKUNHIRAMAN NAIR KRISHADARSAN PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PA 12 ANTSON MATHEW K S/O KANGIRATHINKAV HOUSE PERAMBRA PERUVANNAMUZHI PERUVANNAM 13 PRIYA S MANON S/O PUNNAMKANDY KOLLAM KOLLAM KOZHIKODE 14 SAJEESH K S/ORAJAN 9 9 KOTTAMPARA KURUVATTOOR KONOTT KURUVATTUR 15 GIRIJA NAIR W/OKUNHIRAMAN NAIR KRISHADARSAN PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PARAMBIL PONMERI PA 16 RAJEEVAN M K S/OKANNAN MEETHALE KIZHEKKAYIL PERODE THUNERI PERODE 17 VINODKUMAR P K S/O SATHYABHAVAN CHEVAYOOR MARRIKKUNNU CHEVAYUR 18 CHANDRAN M K S/O KATHALLUR PUNNASSERY PUNNASSERY OTHERS 19 BALAKRISHNAN NAIR K S/O M.C.C.BANK LTD KALLAI ROAD KALLAI ROAD KALLAI ROA 20 NAJEEB P S/O ZUHARA MANZIL ERANHIPALAM ERANHIPALAM ERANHIPALA 21 PADMANABHAN T S/O KALLIKOODAM PARAMBA PERUMUGHAM -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

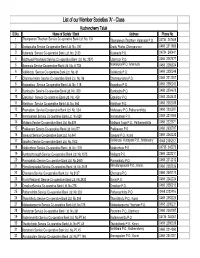

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

Local Self-Government Institutions Government of Kerala

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Local Self-Government Institutions for the year ended March 2016 Government of Kerala Report No.3 of the year 2017 http://www.saiindia.gov.in . TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl. Reference to Title No. Paragraph Pages 1 Preface - v 2 Overview - vii-x CHAPTER I 3 Organisation, devolution and accountability 1 1-7 framework of Local Self-Government Institutions CHAPTER II 4 Finances and financial reporting issues of Local 2 9-23 Self-Government Institutions CHAPTER III – PERFORMANCE AUDIT 5 Implementation of ADB Aided Kerala Sustainable 3.1 25-53 Urban Development Project CHAPTER IV– COMPLIANCE AUDIT AUDIT OF SELECTED TOPICS 6 Installation and Management of Bio-Gas Plants by 4.1 55-73 Urban Local Bodies 7 Procurement of Goods and Services by Local Self 4.2 73-85 Government Institutions OTHER COMPLIANCE AUDIT OBSERVATIONS 8 Unfruitful expenditure of `39.82 lakh due to 4.3 86-87 collapse of a school building 9 Idle investment on the construction of an 4.4 87-89 Agricultural Trading and Marketing Complex 10 Short assessment of Entertainment Tax of 4.5 89-91 Amusement Parks 11 Non-collection of Service Tax from tenants resulted 4.6 91-92 in loss of `27.81 lakh and avoidable interest of `24.07 lakh due to belated filing of declaration 12 Action of Municipality in continuing with the land 4.7 92-94 acquisition process despite not having adequate funds led to avoidable wasteful expenditure of `40.09 lakh 13 Unfruitful expenditure on development of Kole land 4.8 94-96 i Audit Report (LSGIs) Kerala for the year ended March 2016 APPENDICES No. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MIND THE

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MIND THE GAP: CONNECTING NEWS AND INFORMATION TO BUILD AN ANTI-RAPE AND SEXUAL ASSAULT AGENDA IN INDIA Pallavi Guha, Doctor of Philosophy, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Kalyani Chadha, Philip Merrill College of Journalism Professor Linda Steiner, Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation will examine the use of news media and social media platforms by feminist activists in building an anti-rape and sexual assault agenda in India. Feminist campaigns need to resonate and interact with the mainstream media and social media simultaneously to reach broader audiences, including policymakers, in India. For a successful feminist campaign to take off in a digitally emerging country like India, an interdependence of social media conversations and news media discussions is necessary. The study focuses on the theoretical framework of agenda building, digital feminist activism, and hybridization of the media system. The study will also introduce the still-emerging concept of interdependent agenda building to analyze the relationship between news media and social media. This concept proposes the idea of an interplay of information between traditional mass media and social media, by focusing not just on one media platform, but on multiple platforms simulataneous in this connected world. The methodology of the study includes in-depth interviews with thirty-five feminist activists and thirty journalists; thematic analysis of 550 newspaper reports of three rapes and murders from 2005-2016; and social media analysis of three Facebook feminist pages to understand and analyze the impact of social media on news media coverage of rape and the combined influence of media platforms on anti-rape feminist activism. -

A Study on Women Reservation in Urban Local Government in Tamil Nadu in with Special Reference to Athoor Block

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 7 Issue 7, July 2017, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A A Study on Women Reservation in Urban Local Government in Tamil Nadu in with Special Reference to Athoor Block S. Sirajtheen* Abstract In ancient time to modern time the women have a lot of problem like, domestic problem, social, cultural, economical problem to facing the women. Because of the society was defined by women as a weaker section. Not only these problems are main reason, financial problems also created by problem of one of the women development. So for the women reservation scheme was very useful to the development or empower of the best level of status also creating by this women reservation scheme. The women problem bases various leader have a more straggle again women discrimination in our country and then there bases lost of straggle to emerging so the women get a reservation. Mahatma Gandhi fasted in protest against it but many among the depressed classes, including their leader, B. R. Ambedkar, favored it. After negotiations, Gandhi reached an agreement with Ambedkar to have a single Hindu electorate, with Dalits having seats reserved within it. Electorates for other religions, such as Islam and Sikhism, remained separate. This became known as the Poona Pact. -

PROCEEDINGS of the DISTRICT JUDGE, KOZHIKODE Present: Sri.V

PROCEEDINGS OF THE DISTRICT JUDGE, KOZHIKODE Present:- Sri.V.Bhaskaran, District Judge. Sub:- Estt- District Court, Kozhikode ± Promotion, Transfer and Posting of Staff ± Orders Issued. Read :-1. Representation dated 20-01-2015 put in by Sri.Sajish.P.,Munsiff-Magistrate Court, Payyoli. 2. Application for transfer dated 15-1-15 put in by Smt.Ravitha.T. Process Server, Munsiff-Magistrate Court, Payyoli. 3. Application for transfer dated 05-06-2014 put in by Sri.Majeed.K.C., Process Server, District Court, Kozhikode. 4. Application for transfer dated 07-11-2014 put in by Sri.O.Jayarajan, Process Server, District Court, Kozhikode. 5. Application for transfer dated 15-11-2014 put in by Sri.Shyju.T.P., Process Server, Sub Court, Koyilandy. 6. Representation dated 3-4-14 put in by Sri.Shyju.K., Duffedar, Special Addl Sessions Court (Marad Cases), Kozhikode. .............. ORDER NO. A1-30/2015. Kozhikode, Dated: 27.01.2015. Referring to the above, the following Orders of Promotion, transfer and posting of members of staff are issued. 1. Sri.Viswanathan.E.P., Process Server, District Court, Kozhikode is transferred and posted as such to the Office of the Wakf Tribunal / III Additional District & Sessions Court, Kozhikode in the existing vacancy. 2. Sri.Sajish.P., Process Server, Munsiff-Magistrate Court, Payyoli is appointed as Court Keeper, transferred and posted as such to the Munsiff©s Court, Vatakara. Vice Sl. No.7. 3. Smt.Ravitha.T., Process Server, Munsiff-Magistrate Court, Payyoli is transferred and posted as such to the Sub Court, Koyilandy in the existing vacancy. 4. Sri.Majeed.K.C., Process Server, District Court, Kozhikode is transferred and posted as such to the Sub Court, Koyilandy in the existing vacancy.