Survey of Neotropical Otters: Testing Methods to Access Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R E P O R T NOTES on NEOTROPICAL OTTER (Lontra

IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35(4) 2018 R E P O R T NOTES ON NEOTROPICAL OTTER (Lontra longicaudis) HUNTING, A POSSIBLE UNDERESTIMATED THREAT IN COLOMBIA Diana MORALES-BETANCOURT1 , Oscar Daniel MEDINA BARRIOS2 1Universidad Externado de Colombia, Cl. 12 #1-17 Este, Bogotá, Colombia, [email protected] 2Animal Care Coordinator, Fundación Botánica y Zoológica de Barranquilla, Cl. 77 #68-40 Barranquilla, Colombia, [email protected] (Received 12th March 2018, accepted 15th June 2018) ABSTRACT: Since Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) hunting was legally banned in 1973 in Colombia, hunting is no longer considered to be a high priority conservation concern in the Country. The species is still classified as Vulnerable in the country, but the National Mammals Red List and the National action plan for aquatic mammals’ conservation in Colombia do not consider any use of the species besides keeping it as pet (an illegal activity in Colombia). A preliminary survey to identify current hunting activity was conducted professionals at biological research institutions, environmental NGO’s, university professors and regional environmental authorities, to identify current hunting among the five ecoregions in Colombia. The overall results among ecoregions show the main reasons for hunting Neotropical otters are: keeping as pet (29%), pelt use (24%) and bushmeat (22%). The results create a basis for gathering more information on the hunting of Neotropical otters in Colombia. Keywords: Bushmeat, Colombia, hunting, Lontra longicaudis, Neotropical otter, wildlife use. Citation: Morales-Betancourt, D and Medina Barrios, OD (2018). Notes on Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) Hunting, a Possible Underestimated Threat in Colombia . IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. -

Otter News No. 124, July 2021

www.otter.org IOSF Otter News No. 124, July 2021 www.loveotters.org Otter News No. 124, July 2021 Join our IOSF mailing list and receive our newsletters - Click on this link: http://tinyurl.com/p3lrsmx Please share our news Good News for Otters in Argentina Giant otters are classified as “extinct” in Argentina but there have been some positive signs of their return in recent months. The Ibera wetlands lie in the Corrientes region and are one of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystems. Rewilding Argentina is attempting to return the country’s rich biodiversity to the area with species such as jaguars, macaws and marsh deer. They have also been working to bring back giant otters and there have been some small successes and three cubs have recently been born as offspring of two otters that were reintroduced there. And there is more good news for the largest otter species. In May there was the first sighting of “wild” giant otters in Argentina for 40 years! Furthermore, there have been other success stories for otters across the south American nation. Tierra del Fuego, Argentina’s southern-most province, has banned all open-net salmon farming. This ban will help protect the areas fragile marine ecosystems, which is home to half of Argentina’s kelp forests which support species such as the southern river otter. This also makes Argentina the first nation in the world to ban such farming practices. With so many problems for otter species it is encouraging to see some steps forward in their protection in Argentina. -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Diversity of Mammals and Birds Recorded with Camera-Traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco

Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Parag. Vol. 24, nº 1 (Jul. 2020): 5-14100-100 Diversity of mammals and birds recorded with camera-traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco Diversidad de mamíferos y aves registrados con cámaras trampa en el Chaco Húmedo Paraguayo Andrea Caballero-Gini1,2,4, Diego Bueno-Villafañe1,2, Rafaela Laino1 & Karim Musálem1,3 1 Fundación Manuel Gondra, San José 365, Asunción, Paraguay. 2 Instituto de Investigación Biológica del Paraguay, Del Escudo 1607, Asunción, Paraguay. 3 WWF. Bernardino Caballero 191, Asunción, Paraguay. 4Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract.- Despite its vast extension and the rich fauna that it hosts, the Paraguayan Humid Chaco is one of the least studied ecoregions in the country. In this study, we provide a list of birds and medium-sized and large mammals recorded with camera traps in Estancia Playada, a private property located south of Occidental region in the Humid Chaco ecoregion of Paraguay. The survey was carried out from November 2016 to April 2017 with a total effort of 485 camera-days. We recorded 15 mammal and 20 bird species, among them the bare-faced curassow (Crax fasciolata), the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), and the neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis); species that are globally threatened in different dregrees. Our results suggest that Estancia Playada is a site with the potential for the conservation of birds and mammals in the Humid Chaco of Paraguay. Keywords: Species inventory, Mammals, Birds, Cerrito, Presidente Hayes. Resumen.- A pesar de su vasta extensión y la rica fauna que alberga, el Chaco Húmedo es una de las ecorregiones menos estudiadas en el país. -

Medium to Large Size Mammals of Southern Serra Do Amolar, Mato Grosso Do Sul, Brazilian Pantanal

This is a repository copy of Medium to large size mammals of southern Serra do Amolar, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazilian Pantanal. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/98067/ Version: Published Version Article: Porfirio, Grasiela, Sarmento, Pedro, Xavier Filho, Nilson Lino et al. (2 more authors) (2014) Medium to large size mammals of southern Serra do Amolar, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazilian Pantanal. Check List. pp. 473-482. ISSN 1809-127X 10.15560/10.3.473 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Check List 10(3): 473–482, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Medium to large size mammals of southern Serra do PECIES Amolar, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazilian Pantanal S OF 1,2*, Pedro Sarmento 1, Nilson Lino Xavier Filho 2, Joana Cruz 3 and Carlos Fonseca 1 ISTS L Grasiela1 University Porfirio of Aveiro, Biology Department and CESAM – Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e do Mar. -

Pages PDF 2.8 MB

IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 38(2) 2021 N O T E F R O M T H E E D I T O R NOTE FROM THE EDITOR Dear Friends, Colleagues and Otter Enthusiasts! I can only hope that you all are safe and healthy. I understood that some are already vaccinated. For the rest I hope we all manage to stay safe and healthy until it is our turn. This year we are now much faster than in previous years to get manuscripts online. We are hard working with Lesley to remove all the backlog to the point when we will be able to upload each manuscript on the date the proofprint has been accepted by the authors. You may be well aware that the IUCN OSG Bulletin, via me, became a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) some years ago. As part of this, I sometimes use anti-plagiarism software to check manuscripts before sending them out for review. Another aspect is that authors submitting manuscripts should carefully consider the list of authors as there are strict rules on how to add an additional author after the original submission, which creates a lot of work for me and them. I want to use the opportunity to ask all authors to carefully double check their reference, and the list of references. It is so much work for Lesley to sort this out and then, especially, find the missing references. Many thanks to Lesley for all endless hours and hours spent not only for getting manuscripts online but also doing the extra work to double-check the manuscripts for typos and the one always missing reference. -

Animal Inspected at Last Inspection

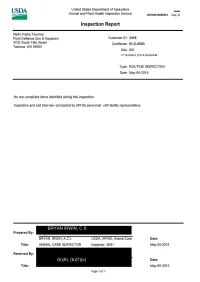

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3432 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 10-AUG-16 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3432 86-C-0001 001 ARIZONA CENTER FOR NATURE 10-AUG-16 CONSERVATION Count Species 000003 Cheetah 000005 Cattle/cow/ox/watusi 000003 Mandrill *Male 000006 Hamadryas baboon 000004 Grevys zebra 000008 Thomsons gazelle 000002 Cape Porcupine 000002 Lion 000002 African hunting dog 000002 Tiger 000008 Common eland 000002 Spotted hyena 000001 White rhinoceros 000007 Spekes gazelle 000005 Giraffe 000004 Kirks dik-dik 000002 Fennec fox 000003 Ring-tailed lemur 000069 Total ARHYNER United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2016082567967934 Insp_id Inspection Report Arizona Center For Nature Conservation Customer ID: 3432 455 N. Galvin Parkway Certificate: 86-C-0001 Phoenix, AZ 85008 Site: 001 ARIZONA CENTER FOR NATURE CONSERVATION Type: ROUTINE INSPECTION Date: 19-OCT-2016 No non-compliant items identified during this inspection. This inspection and exit interview were conducted with the primate manager. Additional Inspectors Gwendalyn Maginnis, Veterinary Medical Officer AARON RHYNER, D V M Prepared By: Date: AARON RHYNER USDA, APHIS, Animal Care 19-OCT-2016 Title: VETERINARY MEDICAL OFFICER 6077 Received By: (b)(6), (b)(7)(c) Date: Title: FACILITY REPRESENTATIVE 19-OCT-2016 Page 1 of 1 United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3432 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 19-OCT-16 -

Mammalian and Avian Diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana

Biota Neotrop., vol. 11, no. 3 Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles1,2, Niall Patrick McCann1 & Ashley Peregrine Holland1 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, School of Biosciences,Cardiff University, Museum Avenue, Cardiff, Wales, CF103AX Rupununi River Drifters, Karanambu Ranch, Lethem Post Office, Region 9, Rupununi Guyana 2Corresponding author: Robert Stuart Alexander Pickles, e-mail: [email protected] PICKLES, R.S.A., McCANN, N.P. & HOLLAND, A.L. Mammalian and avian diversity of the Rewa Head, Rupununi, Southern Guyana. Biota Neotrop. 11(3): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n3/en/abstract?in ventory+bn00911032011 Abstract: We report the results of a short expedition to the remote headwaters of the River Rewa, a tributary of the River Essequibo in the Rupununi, Southern Guyana. We used a combination of camera trapping, mist netting and spot count surveys to document the mammalian and avian diversity found in the region. We recorded a total of 33 mammal species including all 8 of Guyana’s monkey species as well as threatened species such as lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and bush dog (Speothos venaticus). We recorded a minimum population size of 35 giant otters in five packs along the 95 km of river surveyed. In total we observed 193 bird species from 47 families. With the inclusion of Smithsonian Institution data from 2006, the bird species list for the Rewa Head rises to 250 from 54 families. These include 10 Guiana Shield endemics and two species recorded as rare throughout their ranges: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). -

990 PART 23—ENDANGERED SPECIES CONVENTION Subpart A—Introduction

Pt. 23 50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–01 Edition) Service agent, or other game law en- 23.36 Schedule of public meetings and no- forcement officer free and unrestricted tices. access over the premises on which such 23.37 Federal agency consultation. operations have been or are being con- 23.38 Modifications of procedures and nego- ducted; and shall furnish promptly to tiating positions. such officer whatever information he 23.39 Notice of availability of official re- may require concerning such oper- port. ations. Subpart E—Scientific Authority Advice (c) The authority to take golden ea- [Reserved] gles under a depredations control order issued pursuant to this subpart D only Subpart F—Export of Certain Species authorizes the taking of golden eagles when necessary to seasonally protect 23.51 American ginseng (Panax domesticated flocks and herds, and all quinquefolius). such birds taken must be reported and 23.52 Bobcat (Lynx rufus). turned over to a local Bureau Agent. 23.53 River otter (Lontra canadensis). 23.54 Lynx (Lynx canadensis). 23.55 Gray wolf (Canis lupus). PART 23—ENDANGERED SPECIES 23.56 Brown bear (Ursus arctos). CONVENTION 23.57 American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Subpart A—Introduction AUTHORITY: Convention on International Sec. Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna 23.1 Purpose of regulations. and Flora, 27 U.S.T. 1087; and Endangered 23.2 Scope of regulations. Species Act of 1973, as amended, 16 U.S.C. 23.3 Definitions. 1531 et seq. 23.4 Parties to the Convention. SOURCE: 42 FR 10465, Feb. 22, 1977, unless Subpart B—Prohibitions, Permits and otherwise noted. -

Standards for Caniform Sanctuaries

Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries Standards For Caniform Sanctuaries Version: February, 2018 ©2012 Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries – Standards for Caniform Sanctuaries Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................... 1 GFAS PRINCIPLES ................................................................................................................................................... 1 ANIMALS COVERED BY THESE STANDARDS ............................................................................................................ 1 STANDARDS UPDATES……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 CANIFORM STANDARDS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 CANIFORM HOUSING ............................................................................................................................ 5 H-1. Types of Space and Size ..................................................................................................................................... 5 H-2. Containment ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 H-3. Ground and Plantings ........................................................................................................................................ -

AWA IR C-WA Secure.Pdf

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3416 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 04-MAY-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3416 91-C-0003 001 METRO PARKS TACOMA 04-MAY-15 Count Species 000001 Canadian lynx 000006 Harbor seal 000001 Reindeer 000001 Dog Adult 000003 Muskox 000010 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Oriental small-clawed otter 000007 Clouded leopard 000002 Anoa 000001 Kinkajou 000001 Indian flying fox 000002 Asiatic elephant 000001 Striped skunk 000002 White-nosed coati 000002 Arctic fox 000001 Fishing cat 000003 Walrus 000001 Prehensile-tailed porcupine 000001 Dromedary camel 000001 Southern three-banded armadillo 000001 American beaver 000006 Sea otter 000002 White-cheeked gibbon 000004 Indian crested porcupine 000006 Tiger 000003 Polar bear 000011 Goat 000001 Black lemur 000002 Siamang 000002 Siamang 000001 Aardvark Red wolf 000001 Linnes two-toed sloth 000002 Straw-coloured fruit bat 000003 Parma wallaby 000003 Ring-tailed lemur 000002 European rabbit 000006 Dumbo Rat 000001 Four-toed hedgehog 000019 Damaraland Mole Rat Count Species 000127 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3416 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 09-JUL-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3416 91-C-0003 001 METRO PARKS TACOMA 09-JUL-14 Count Species 000001 Canadian lynx 000006 Harbor seal 000003 Reindeer 000001 Dog Adult 000004 Muskox 000017 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Oriental small-clawed -

Of Wild Animals Infected with Zoonotic Leishmania

microorganisms Review A Systematic Review (1990–2021) of Wild Animals Infected with Zoonotic Leishmania Iris Azami-Conesa 1, María Teresa Gómez-Muñoz 1,* and Rafael Alberto Martínez-Díaz 2 1 Department of Animal Health, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, University Complutense of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, and Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, University Autónoma of Madrid, 28029 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Leishmaniasis are neglected diseases caused by several species of Leishmania that affect humans and many domestic and wild animals with a worldwide distribution. The objectives of this review are to identify wild animals naturally infected with zoonotic Leishmania species as well as the organs infected, methods employed for detection and percentage of infection. A literature search starting from 1990 was performed following the PRISMA methodology and 161 reports were in- cluded. One hundred and eighty-nine species from ten orders (i.e., Carnivora, Chiroptera, Cingulata, Didelphimorphia, Diprotodontia, Lagomorpha, Eulipotyphla, Pilosa, Primates and Rodentia) were reported to be infected, and a few animals were classified only at the genus level. An exhaustive list of species; diagnostic techniques, including PCR targets; infected organs; number of animals explored and percentage of positives are presented. L. infantum infection was described in 98 wild species and L.(Viania) spp. in 52 wild animals, while L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, L. major and L. tropica Citation: Azami-Conesa, I.; were described in fewer than 32 animals each. During the last decade, intense research revealed new Gómez-Muñoz, M.T.; Martínez-Díaz, hosts within Chiroptera and Lagomorpha.