Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Struggle

Part I. Quest for Equality: The Political Struggle 1: Address to the 1965 London Constitutional Conference, 26 July 1965 I thank you [Secretary of State Anthony Greenwood] and the United Kingdom Government for the kind invitation and welcome extended us to this historic conference which is called to smelt the existing system of government in the Colony of Fiji and to forge and mould a new constitution which, I hope, will lead our country to complete independence in the not too distant future. Political liberty, equality and fraternity rank foremost among the good things of life, and mankind all over the world cherishes and holds these ideals close to its heart. The people of Fiji are no exception. Without political freedom, no country can be economically, socially or spiritually free. We in Fiji, as in many undeveloped countries of the world, are faced with the three most formidable enemies of mankind, namely, Poverty, Ignorance, and Disease. We need political freedom to confront these enemies and free our minds, bodies and souls from their clutches. Needless to say, when I refer to political freedom, I mean democracy under the rule of law, the sort of freedom which the British people and the people of United States enjoy. We need freedom which will politically, economically and socially integrate the various communities living in Fiji and make out of them one nation deeply conscious of the responsibilities and tasks which lie ahead. I call this conference important and historic because it is the first conference of its kind in the history of Fiji and it may very well prove the beginning of the end of a form of government which stands universally condemned in the modern world. -

Alignment Mouth Demonstrations in Sign Languages Donna Jo Napoli

Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Donna Jo Napoli, Swarthmore College, [email protected] Corresponding Author Ronice Quadros, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, [email protected] Christian Rathmann, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, [email protected] 1 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstrations in sign languages Abstract: Non-manual articulations in sign languages range from being semantically impoverished to semantically rich, and from being independent of manual articulations to coordinated with them. But, while this range has been well noted, certain non-manuals remain understudied. Of particular interest to us are non-manual articulations coordinated with manual articulations, which, when considered in conjunction with those manual articulations, are semantically rich. In which ways can such different articulators coordinate and what is the linguistic effect or purpose of such coordination? Of the non-manual articulators, the mouth is articulatorily the most versatile. We therefore examined mouth articulations in a single narrative told in the sign languages of America, Brazil, and Germany. We observed optional articulations of the corners of the lips that align with manual articulations spatially and temporally in classifier constructions. The lips, thus, enhance the message by giving redundant information, which should be particularly useful in narratives for children. Examination of a single children’s narrative told in these same three sign languages plus six other sign languages yielded examples of one type of these optional alignment articulations, confirming our expectations. Our findings are coherent with linguistic findings regarding phonological enhancement and overspecification. Keywords: sign languages, non-manual articulation, mouth articulation, hand-mouth coordination 2 Mouth corners in sign languages Alignment mouth demonstration articulations in sign languages 1. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. Language in a Fijian Village An Ethnolinguistic Study Annette Schmidt A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. September 1988 ABSTRACT This thesis investigates sociolinguistic variation in the Fijian village of Waitabu. The aim is to investigate how particular uses, functions and varieties of language relate to social patterns and modes of interaction. ·The investigation focuses on the various ways of speaking which characterise the Waitabu repertoire, and attempts to explicate basic sociolinguistic principles and norms for contextually appropriate behaviour.The general purpose is to explicate what the outsider needs to know to communicate appropriately in Waitabu community. Chapter one discusses relevant literature and the theoretical perspective of the thesis. I also detail the fieldwork setting, problems and restrictions, and thesis plan. Chapter two provides the necessary background information to this study, describing the geographical, demographical and sociohistorical setting. Description is given of the contemporary language situation, structure of Fijian (Bouma dialect), and Waitabu social structure and organisation. In Chapter 3, the kinship system which lies at the heart of Waitabu social organisation, and kin-based sociolinguistic roles are analysed. This chapter gives detailed description of the kin categories and the established modes of sociolinguistic behaviour which are associated with various kin-based social identities. -

Cheibub 104-140.Pdf

The Architecture of Democracy Oxford Studies in Democratization Series Editor: Laurence Whitehead Oxford Studies in Democratization is a series for scholars and students of comparative politics and related disciplines. Volumes will concentrate on the comparative study of the democratization processes that accompanies the decline and termination of the cold war. The geographical focus of the series will primarily be Latin America, the Caribbean, Southern and Eastern Europe, and relevant experiences in Africa and Asia. OTHER BOOKS IN THE SERIESElectoral Systems and Democratization in Southern Africa Andrew Reynolds The Legacy of Human Rights Violations in the Southern Cone: Argeninta, Chile, and Uruguay Luis Roniger and Mario Sznajder Citizenship Rights and Social Movements: A Comparative and Statistical Analysis Joe Foweraker and Todd Landman The International Dimensions of Democratization: Europe and the Americas Laurence Whitehead The Politics of Memory: Transitional Justice in Democratizing Societies Alexandra Barahona de Brito, Carmen González Enríquez, and Paloma Aguilar Democratic Consolidation in Eastern Europe, Volume 1: Institutional Engineering Jan Zielonka Democratic Consolidation in Eastern Europe, Volume 2: International and Transnational Factors Jan Zielonka and Alex Pravda Institutions and Democratic Citizenship Alex Hadenius The Architecture of Democracy Constitutional Design, Conict Management, and Democracy Edited by Andrew Reynolds Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University -

The Harrovian

THE HARROVIAN KING WILLIAM'S COLLEGE MAGAZINE Published three times yearly NUMBER 239 . DECEMBER THE BARRQVIAN 239 DECEMBER 1959 CONTENTS Random Notes School Officers Valete Salvete Library Notes Chapel Notes Correspondence Founder's Day Honours List University Admissions First House Plays ... Literary and Debating Society Literary Contributions Manx Society Gramophone Society Photographic Society Scientific Society Music Club The Orchestra Chess Notes Golf Society Aeronautical Society Badminton Society Shooting Combined Cadet Force ist K.W.C. Scout Group ... Swimming Cricket Rugby Football O.K.W. Section Obituaries Contemporaries We are grateful to the Isle of Man Times and Mona's Herald for permission to reprint photographs in this issue. THE BARROVIAN [December RANDOM NOTES Many friends, parents and O.K.W.'s will be interested to hear that Archdeacon Stenning in his capacity as Chaplain to the Royal Household has been asked to preach in the Chapel Royal on May 8th, 1960, at 10.45 a.m. * # * At the end of this term Mr. B. C. A. Hartley will be handing over as Housemaster of Junior House to Mr. C. Attwood. We should like to take this opportunity of joining the very large numbers of ex- Junior House boys and their parents who would like to thank Mr. Hartley for all the help and encouragement that he has given at Junior House for over twenty years. To say more at this stage would be to anticipate Mr. Hartley s retirement, an event happily many years distant. * * # We congratulate Dr. C. A. Caine (1942-49) who was elected into a Fellowship as Tutor in Mathematics at St. -

Brij Lal's Biography of AD Patel

18 Fijian Studies Vol 13, No. 1 tory cannot be written without some bias and selective emphasis. The book well illustrates historian David Lowenthal’s dictum: ‘History is per- suasive because it is organised by and filtered through individual minds, not in spite of that fact. Subjective interpretation gives it life and mean- Brij Lal's Biography of A D Patel - A Vision for Change: ing’ (1985: 218). A.D. Patel and the Politics of Fiji Chapter 1, Retrospect, sketches the emergence of Indian society and politics in Fiji - the setting into which Patel stepped at the age of only 23 Robert Norton in 1928, soon to join the leadership of the campaign for political equality with the minority European community under a common roll electoral 3 system. The common franchise campaign was abandoned in the early A.D. Patel and Ratu Kamisese Mara were the outstanding political 1930s and not revived until the 1960s, this time with Patel in the lead. leaders and adversaries during Fiji’s transition from colonial rule to inde- Chapter 2, Child of Gujarat, is one of the most illuminating sections pendence. People who can recall the Fiji of the 1960s will have vivid of the book, describing aspects of life in Gujarat early last century which memories of Ambalal Dayhabhai Patel, Ratu Mara's resolute but not un- profoundly influenced Patel's outlook and dispositions. He was the pam- sympathetic opponent on the political stage. India-born Patel (1905-1969) pered first-born in a landed farming family of the Patidar group, the most was the leading advocate for the common franchise and the founding economically and politically powerful class in the Kheda district. -

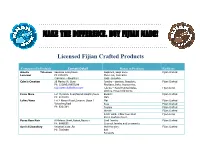

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Company and Kisan

Chapter 4: Company and Kisan The relations between the Company and the growers was strong reminiscent of barons and serfs during the Middle Ages. They had to take what was given to them and be thankful for the small mercies whether they liked it or not. A.D. Patel, 1943 I am convinced that I was taking up a true and just cause and I am convinced that the stand I took and the advice I gave to the growers was right and I am proud of the part I played in that dispute. A.D. Patel, 1945 On 12 January 1938, Padri Mehar Singh, Saiyyid Latif Shah and Pandit Ajodhya Prasad went to A.D. Patel’s office in Nadi.1 They had just formed a farmers association, the Kisan Sangh, and wanted Patel to become one of its leaders. They failed to persuade Patel. According to Prasad, Patel refused to become involved. Confronting the CSR, Patel reportedly said, was like battering one’s head against the mountains of Sabeto. There was no organisation in Fiji which was strong enough to confront the Company, said Patel, and urged the three men to go home and forget about their foolish project. When Shah persisted and reminded Patel of how bad leadership and ignorance of the law had cost Indians dearly in the 1920 strike, Patel, according to Prasad, reportedly said unbelievably: ‘I’ll gladly pull the trigger if I find the government pointing its machine gun towards Indians.’ Unsuccessful in their mission, the three men left Patel’s office and went to a shady spot under a tree nearby to ponder Patel’s motives. -

Out-Of-School Children: a Contemporary View from the Pacific Island Countries of the Commonwealth

C O L C O L Out-of-School Children: A Contemporary View from the Pacific Island Countries of the Commonwealth Sharishna Narayan With support from Tony Mays Som Naidu Kirk Perris Out-of-School Children: A Contemporary View from the Pacific Island Countries of the Commonwealth Sharishna Narayan With support from Tony Mays Som Naidu Kirk Perris The Commonwealth of Learning (COL) is an intergovernmental organisation created by Commonwealth Heads of Government to encourage the development and sharing of knowledge, resources and technologies in open learning and distance education. Commonwealth of Learning, 2021 © 2021 by the Commonwealth of Learning. Out-of-School Children: A Contemporary View from the Pacific Island Countries of the Commonwealth is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. For avoidance of doubt, by applying this licence, the Commonwealth of Learning does not waive any privileges or immunities from claims that they may be entitled to assert, nor does the Commonwealth of Learning submit itself to the jurisdiction, courts, legal processes or laws of any jurisdiction. ISBN: 978-1-7772648-4-0 Cover photo: M M from Switzerland, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons Published by: COMMONWEALTH OF LEARNING 4710 Kingsway, Suite 2500 Burnaby, British Columbia Canada V5H 4M2 Telephone: +1 604 775 8200 Fax: +1 604 775 8210 Web: www.col.org Email: [email protected] Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................ viii Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................... ix 1. Overview ..................................................................................................... 1 Exploratory Study of Out-of-School Children (OOSC) in the Pacific: 2. -

THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2015 By

AS INTRODUCED IN LOK SABHA Bill No. 90 of 2015 THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2015 By SHRI ASHWINI KUMAR CHOUBEY, M.P. A BILL further to amend the Constitution of India. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Sixty-sixth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. This Act may be called the Constitution (Amendment) Act, 2015. Short title. 2. In the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution,— Amendment of the Eighth (i) existing entries 1 and 2 shall be renumbered as entries 2 and 3, respectively, Schedule. 5 and before entry 2 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— "1. Angika."; (ii) after entry 3 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— "4. Bhojpuri."; and (iii) entries 3 to 22 shall be renumbered as entries 5 to 24, respectively. STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS Language is not only a medium of communication but also a sign of respect. Language also reflects on the history, culture, people, system of governance, ecology, politics, etc. 'Bhojpuri' language is also known as Bhozpuri, Bihari, Deswali and Khotla and is a member of the Bihari group of the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family and is closely related to Magahi and Maithili languages. Bhojpuri language is spoken in many parts of north-central and eastern regions of this country. It is particularly spoken in the western part of the State of Bihar, north-western part of Jharkhand state and the Purvanchal region of Uttar Pradesh State. Bhojpuri language is spoken by over forty million people in the country. -

The 1965 Constitutional Conference

4. The 1965 Constitutional Conference The stand-off between Sir Derek Jakeway and A. D. Patel took place during a familiarisation visit to Fiji by parliamentary undersecretary of state, Eirene White, in what was now a Labour government in Britain. Her task was to report back on issues that might be raised at the forthcoming constitutional conference. She heard a wide range of opinion: from Muslims about separate representation, from Fijians about their special interests Ð including political leadership of the country Ð from the ever mercurial Apisai Tora about deporting Indo-Fijians as Ceylon and Burma had done, from the Council of Chiefs reiterating the terms of the Wakaya Letter, from Indian leaders about common roll and the need to promote political integration, from journalist Alipate Sikivou expressing the Fijian nationalist line that the Indians could always go back to India, the Chinese to China and the Rotumans and other islanders to their respective islands but the Fijians, the indigenous people, had Fiji as their only home. Sikivou was not alone in holding such extreme views. Many others were of the view that, as Ratu Penaia Ganilau and Ratu George Cakobau had said in 1961, at independence, Fiji should be returned to the Fijians. As Uraia Koroi put it at a meeting of the Fijian Association in January 1965, chaired by Ratu Mara, `Fijians were determined to achieve this claim of right [returning Fiji to Fijians] at the cost of their lives. Bloodshed would mean nothing if their demands were not acceptable to other races in the Colony.'1 -

Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification Alexandre François

Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification Alexandre François To cite this version: Alexandre François. Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification. Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn. The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, Routledge, pp.161-189, 2014, 978-0-41552-789-7. 10.4324/9781315794013.ch6. halshs-00874726v2 HAL Id: halshs-00874726 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00874726v2 Submitted on 19 Mar 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics Edited by Claire Bowern and Bethwyn Evans RH of Historical Linguistics BOOK.indb iii 3/26/2014 1:20:21 PM 6 Trees, waves and linkages Models of language diversifi cation Alexandre François 1 On the diversifi cation of languages 1.1 Language extinction, language emergence The number of languages spoken on the planet has oscillated up and down throughout the history of mankind.1 Different social factors operate in opposite ways, some resulting in the decrease of language diversity, others favouring the emergence of new languages. Thus, languages fade away and disappear when their speakers undergo some pressure towards abandoning their heritage language and replacing it in all contexts with a new language that is in some way more socially prominent (Simpson, this volume).