Company and Kisan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AD Patel Sub-Index

Bandranaike, SWRD 27 Index Bannerji, Surendranath 27 Barker, Ray 186 fn Barrett, WM 239 Agent General of Immigration 13 basic tax 177 Agent, of Government of India 15-16 Bayly, JP 133, 137, 139 Agreement 24 July 138-139 Beattie, Hamilton 38 Agricultural Bank 143 Ben, Leela 105 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bill Bennett, JM 145 174-176 Besant, Annie 28 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bhajan mandalis 119 Committee 176 Bharat Mata Day 110 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bhindi, PK 230 Ordinance 237 Bill of Rights 199, 206 agricultural production, Second World : in Federation Party manifesto 234 War 84 Blunt, Edward 8 AJC Patel and Company 36 Book Box Scheme 168 Akhil Fiji Krishak Maha Sangh See Maha Bowden, Herbert 226 Sangh boycott of Legislative Council, 1929 39 Ali, Ahmed 242 Brennan, Sir Gerard ix-x, 242 All-Fiji Indian conference 1929 46 British Council 168 Alliance Party 219, 249 British India Association 13 : by-election 1967 230, 236 British Phosphate Commission 224 : formation of 207 Brown, Doug xix : response to Federation Party Buksh, MS 108 manifesto 235 Buksh, Nabi 40 Amery, Julian 143-144, 161 Buli 47 Amery, LS 41 Bull, PJ 142 Andrews, CF 11, 28, 38 Burns Commission 220 Anthony, James 129 Burns, Sir Alan 184 Archibald, Fred 204 Burton, JW 11, 28 Arya Samaj 12, 33, 37 See also education, bus industry 162 Indian by-election 1967 229-230, 231 : Deo’s influence 109 : Fijian response 237 : elections 1937 49 : results 236-237 : elections 1963 160 : in 1950s elections 111 Cakobau, Ratu Edward xv, 203, 227 : prohibition debate -

Brij Lal's Biography of AD Patel

18 Fijian Studies Vol 13, No. 1 tory cannot be written without some bias and selective emphasis. The book well illustrates historian David Lowenthal’s dictum: ‘History is per- suasive because it is organised by and filtered through individual minds, not in spite of that fact. Subjective interpretation gives it life and mean- Brij Lal's Biography of A D Patel - A Vision for Change: ing’ (1985: 218). A.D. Patel and the Politics of Fiji Chapter 1, Retrospect, sketches the emergence of Indian society and politics in Fiji - the setting into which Patel stepped at the age of only 23 Robert Norton in 1928, soon to join the leadership of the campaign for political equality with the minority European community under a common roll electoral 3 system. The common franchise campaign was abandoned in the early A.D. Patel and Ratu Kamisese Mara were the outstanding political 1930s and not revived until the 1960s, this time with Patel in the lead. leaders and adversaries during Fiji’s transition from colonial rule to inde- Chapter 2, Child of Gujarat, is one of the most illuminating sections pendence. People who can recall the Fiji of the 1960s will have vivid of the book, describing aspects of life in Gujarat early last century which memories of Ambalal Dayhabhai Patel, Ratu Mara's resolute but not un- profoundly influenced Patel's outlook and dispositions. He was the pam- sympathetic opponent on the political stage. India-born Patel (1905-1969) pered first-born in a landed farming family of the Patidar group, the most was the leading advocate for the common franchise and the founding economically and politically powerful class in the Kheda district. -

Research Commons at The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. An Elusive Dream: Multiracial Harmony in Fiji 1970 - 2000 A thesis submitted to the University of Waikato for the degree of Master of Philosophy, January, 2007. by Padmini Gaunder Abstract The common perception of Fiji, which is unique in the South Pacific, is that of an ethnically divided society with the indigenous and immigrant communities often at loggerheads. This perception was heightened by the military coups of 1987, which overthrew the democratically elected government of Dr. Timoci Bavadra because it was perceived as Indian-dominated. Again in 2000, the People’s Coalition Government headed by an Indian, Mahendra Chaudhry, was ousted in a civilian coup. Yet Fiji had been genuinely multiethnic for several decades (even centuries) before it became a colony in 1874. -

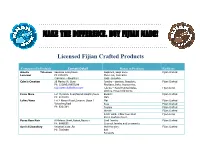

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Chapter 7: Fire in the Cane Fields

Chapter 7: Fire in the Cane Fields The growers are neither slaves, servants nor serfs of the Company. As far as they are concerned, there is no going back to the pre-war conditions. A.D. Patel, 1960 A militant leader is a leader who stand for and insists upon fair play, who refuses to be a tool in the hands of the employer and who stands firm whatever the colonial vested interests say; The salvation of the working classes in this country will largely depend on the so-called militant and irresponsible leaders. A.D. Patel, 1963 The lull of the 1950s came to a sudden, turbulent halt in December 1959, when the Wholesale and Retail General Workers Union, led by Apisai Tora and James Anthony, struck for better wages from the Shell Oil and Vacuum Oil companies. The strike and the ensuing violence against European-owned businesses in Suva shook the city to its foundations, questioning many of the assumptions that underpinned the colonial order. Fijians and Indo-Fijians joining hands against expatriate companies was a rare, and frightening, sight for the colonial authorities to witness, especially when they had done their best to create institutions and structures to keep the two main groups apart from each other. Inevitably perhaps, the strike strained race relations in a colony where race relations were never warm anyway. The strike failed because of the combined opposition of the colonial government and Fijian leaders who ordered their people not ‘to bite the hand that feeds you.’1 Even so, it deeply influenced political thinking in influential circles in Fiji for the rest of the next decade. -

Elections and Politics in Contemporary Fiji

Chiefs and Indians: Elections and Politics in Contemporary Fiji Brij V. Lal 1he Republic of Fiji went to the polls in May 1992, its first election since the military coups of 1987 and the sixth since 1970, when the islands became independent from Great Britain. For many people in Fiji and out side, the elections were welcome, marking as they did the republic's first tentative steps toward restoring parliamentary democracy and interna tional respectability, and replacing rule by decree with rule by constitu tionallaw. The elections were a significant event. Yet, hope mingles eerily with apprehension; the journey back to genuine representative democracy is fraught with difficulties that everyone acknowledges but few know how to resolve. The elections were held under a constitution rejected by half of the pop ulation and severely criticized by the international community for its racially discriminatory, antidemocratic provisions. Indigenous Fijian po litical solidarity, assiduously promoted since the coups, disintegrated in the face of the election-related tensions within Fijian society. A chief-spon sored political party won 30 of the 37 seats in the 7o-seat House of Repre sentatives, and was able to form a government only in coalition with other parties. Sitiveni Rabuka, the reluctant politician, became prime minister after gaining the support of the Fiji Labour Party, which he had over thrown in 1987, and despite the opposition of his predecessor and para mount chief of Lau, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara. In a further irony, a consti tutional system designed to entrench the interests of Fijian chiefs placed a commoner at the national helm. -

Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: 5 Constitutions, Coups, and Indo

Kaplan, Martha (2018): Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: Constitutions, Coups, and Indo- Fijian Citizenship. In: Elfriede Hermann and Antonie Fuhse (eds.): India Beyond India: Dilem- mas of Belonging. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press (Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology, 12), pp. 83–98. Doi: 10.17875/gup2020-1265 5 Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: Constitutions, Coups, and Indo-Fijian Citizenship Martha Kaplan Introduction: Towards a Historical Anthropology of Dilemmas Postcolonial nation-states and democratic electoral systems were meant to enable self-determination. Yet they have not resolved dilemmas of belonging. The Indo-Fi- jians, descendants of Indians who came to Fiji in the 19th century labor diaspora, are currently a minority in the nation-state which they share with ethnic Fijians, descen- dants of Pacific Islanders resident in the islands. This chapter describes the twentieth century history of how Indo-Fijian anticolonial spokesmen fought for independent Fiji and national belonging with a focus on ‘common roll’ electoral rights. But Fiji’s constitution at independence in 1970 was unusual for its continuation of implacable colonial race categories, its refusal of common roll, and its weighting against Indo- Fijian political representation. And then, a series of coups were mounted by ethnic Fijian military leaders, not Indo-Fijians. Many Indo-Fijians have chosen emigration when possible, seeking self-determination by diaspora. Soberly, this chapter consid- ers the history of plans for Fiji’s democracy embodied in constitutions, elections and other political rituals since 1970, the prospects for self-determination via democracy in Fiji, and the conditions for national belonging for people of Indian descent in Fiji. -

A Majority of Fiji Indians Are the Descendants of the Indentured

Pacific Dynamics: Volume 1 Number 1 July 2017 Journal of Interdisciplinary Research http://pacificdynamics.nz Indo-Fijian Counter Hegemony in Fiji: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 A historical structural approach ISSN: 2463-641X Sanjay Ramesh University of Sydney Abstract Indo-Fijians make up about 37 per cent of Fiji’s current population and have a unique language and culture, which evolved since Indians fist arrived into Fiji as indentured labourers on board the ship Leonidas in 1879. Since their arrival in the British colony as sugar plantation labourers, Indo-Fijian activists led counter hegemonic movements against the colonial government during and after indenture in 1920-21, 1943 and 1960. Indo-Fijian activists demanded political equality with Europeans and constantly agitated for better wages and living conditions through disruptive strikes and boycotts. After independence, the focus of Indo-Fijians shifted to political equality with indigenous Fijians and access to land leases from indigenous landowners on reasonable terms; and these were ongoing themes in the 1972, 1977 and 1982 elections. However, Indo-Fijian counter hegemony took a new form in 1987 with the formation of the multiracial Fiji Labour Party and National Federation Party coalition government but indigenous Fijian nationalists and the military deposed the government and established discriminatory policies against Indo-Fijians which were dismantled by the Fiji Labour Party-led coalition government in 1999. However, indigenous nationalists regrouped and deposed the government in 2000, prompting another round of protests and resistance from Indo-Fijians. Using Gramscian conceptualisation of counter hegemony as disruptive protest, resistance and dissent, I argue that political mobilisation of indentured labourers and their descendants was aimed at restoring political rights, honour, self-respect and dignity lost during colonial and post-colonial periods in Fiji. -

Introduction

Introduction ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,’ AD Patel quoted William Wordsworth’s celebration of the French Revolution as he launched the 1966 election campaign at the Century Theatre in Suva, ‘but to be young was very heaven.’ He was unwell, an acute, insulin-dependent diabetic now also suffering from pneumonia. His mother’s recent death in India would have added to his emotional woes. ‘My voice has failed me today,’ he told his anxious audience long concerned about his failing health. But he was undaunted. ‘Mine is the fortune of being alive in this dawn. Mine is the misfortune that I won’t be able to share the very heaven.’ His premonition of impending mortality sadly proved accurate. Three years later, on 1 October 1969, he died of a massive heart attack at his home in Nadi, almost exactly a year before Fiji became independent from the United Kingdom after ninety-six years of colonial rule. ‘AD was a fine man stubborn, sometimes too much so for comfort,’ wrote QVL Weston on 24 October 1969, ‘but it was through his stubbornness that he got his way, and I think when the tale is told by the historians, it will usually be accepted that his way was right.’ Now the Chief Secretary of Nauru, he had been Commissioner Western based at Lautoka in the early 1960s, witnessing at first hand as the Government’s chief civilian administrator in the sugar belt of Fiji, the first stirrings of political change as Fiji moved haphazardly towards internal self-government and eventually independence. -

388 All Fiji Muslim Political Front 264 All National Congress

Index Agricultural Landlord and Tenants bure lwlou 101; 103 Amendment Act (ALTA) 385; 388 Burt, Sydney 68; 77 All Fiji Muslim Political Front 264 Butadroka, Sakeasi 242; 280; 285; All National Congress (ANC) 377; 383 365ff. Alliance Party (AP) 262-263; 264ff., Cakaudrove 51; 82; 191-192 272ff.; 379 Cakobau 53-57; 60-62; 67-68; 74-79; Ancestral Polynesian Society 183 200; 213; 354 Anderson, Benedict 406-407 Cakobau, Ratu Sir George 284 Apolosi-Bewegung 311; 325ff. Calcutta 131; 133; 140 Armed (Native) Constabulary 77; 219; Calvert, James 98; 108; 197 247;305 Carew; Walter 89 Arya Samaj 260; 334; 362 Cargill, David 38; 93; 98-99; 108 Assembly of God 99 Cargo-Kult 318 Australasian United Steam Navigation CCOP/SOPAC 415 Company 152 Chamberlain, Joseph 221 Australian National University (ANU) Chinese Association 264 13;250 Chinesen 272 Austronesier 182 Chini Mazdur Sangh 157 Ba 51 Church Missionary Society 93 Bahai'i 99 Colonial Sugar Refining Company Baker, Thomas 67 (CSR) 146; 148; 152-155; 161; 251; Bau 39;51; 74ff.;93; 191 254 Baumwolle 113 Colo-Stiimme siehe Kai Colo Bau-Rewa-Krieg 196ff. Confederation of Westem Tui Bavadra, Timothy 178; 269; 288ff.; Association 279 378 Councils 17; 230ff. Bavadra, Vuikaba Adi Kuini 178; 378 Cross, William 38; 93; 98-99; 108 beche-de-mer 46-48; 58; 197 Daily Post 394 blackbirding 126ff Des Voeux; William 139; 228 Black September 296 Deuba-Accord 296 Bligh, William 43 Division 17; 117; Blyth, James 80 Drabuta 122 British Commonewealth ofNatiOlis 11; Dutch East India Company 42; 46 15-16; 24; 297 Dra-ni-Lami 270 British Subjects Society and Volunteers Draunidalo, Savenaca 178 Corps 77 Dreketi 242 Brown & Joske 152 East-West Center (EWC) 13 Bua 51; 71ff.; 82 Edward VII, Konig 213 Bula Tale Communist Party 270 Ellice-Inseln 123 Burebasaga 229; 390-391 Ellis, William 99 Bums, Sir Alan 267 Emperor Gold Mine 156; 293 Bums Philp Ill; 152 Endicott, William 107 461 Ethnizitiit 19; General Electors Association 264; 272 Ethnohistorie 26-27 General Register of Polynesian Evans, F.R. -

Fiji's Tale of Contemporary Misadventure

The GENERAL’S GOOSE FIJI’S TALE OF CONTEMPORARY MISADVENTURE The GENERAL’S GOOSE FIJI’S TALE OF CONTEMPORARY MISADVENTURE ROBBIE ROBERTSON STATE, SOCIETY AND GOVERNANCE IN MELANESIA SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Robertson, Robbie, author. Title: The general’s goose : Fiji’s tale of contemporary misadventure / Robbie Robertson. ISBN: 9781760461270 (paperback) 9781760461287 (ebook) Series: State, society and governance in Melanesia Subjects: Coups d’état--Fiji. Democracy--Fiji. Fiji--Politics and government. Fiji--History--20th century All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2017 ANU Press For Fiji’s people Isa lei, na noqu rarawa, Ni ko sana vodo e na mataka. Bau nanuma, na nodatou lasa, Mai Suva nanuma tiko ga. Vanua rogo na nomuni vanua, Kena ca ni levu tu na ua Lomaqu voli me’u bau butuka Tovolea ke balavu na bula.* * Isa Lei (Traditional). Contents Preface . ix iTaukei pronunciation . xi Abbreviations . xiii Maps . xvii Introduction . 1 1 . The challenge of inheritance . 11 2 . The great turning . 61 3 . Redux: The season for coups . 129 4 . Plus ça change …? . 207 Conclusion: Playing the politics of respect . 293 Bibliography . 321 Index . 345 Preface In 1979, a young New Zealand graduate, who had just completed a PhD thesis on government responses to the Great Depression in New Zealand, arrived in Suva to teach at the University of the South Pacific. -

AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji

for A Vision Change AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji for A Vision Change AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji Brij V Lal THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lal, Brij V. Title: A vision for change : A.D. Patel and the politics of Fiji / Brij V Lal. ISBN: 9781921666582 (pbk.) ISBN: 9781921666599 (ebook) Subjects: Patel, A. D. |q (Ambalal Dahyabhai), 1905-1969. Fiji--Politics and government--20th century. Fiji--History. Dewey Number: 320.099611 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Preface to this Edition . .vii Prologue . ix Chapter 1: Retrospect . 1 Chapter 2: Child of Gujarat . 17 Chapter 3: Into the Fray . 35 Chapter 4: Company and Kisan . 57 Chapter 5: Flesh on the Skeleton . 81 Chapter 6: Interregnum . 105 Chapter 7: Fire in the Cane Fields . 129 Chapter 8: Towards Freedom . 157 Chapter 9: Shaking the Foundations . 183 Chapter 10: Independence Now . 213 Chapter 11: The End in Harness . 241 References . 251 Appendix: Telling the Life of A .D . Patel . 255 Index . 273 v Preface to this Edition This book was first published in 1997 after nearly a decade of interrupted research going back to the early 1980s.