Fiji-Blurb-Cpp 10/5/06 6:48 AM Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AD Patel Sub-Index

Bandranaike, SWRD 27 Index Bannerji, Surendranath 27 Barker, Ray 186 fn Barrett, WM 239 Agent General of Immigration 13 basic tax 177 Agent, of Government of India 15-16 Bayly, JP 133, 137, 139 Agreement 24 July 138-139 Beattie, Hamilton 38 Agricultural Bank 143 Ben, Leela 105 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bill Bennett, JM 145 174-176 Besant, Annie 28 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bhajan mandalis 119 Committee 176 Bharat Mata Day 110 Agricultural Landlord and Tenant Bhindi, PK 230 Ordinance 237 Bill of Rights 199, 206 agricultural production, Second World : in Federation Party manifesto 234 War 84 Blunt, Edward 8 AJC Patel and Company 36 Book Box Scheme 168 Akhil Fiji Krishak Maha Sangh See Maha Bowden, Herbert 226 Sangh boycott of Legislative Council, 1929 39 Ali, Ahmed 242 Brennan, Sir Gerard ix-x, 242 All-Fiji Indian conference 1929 46 British Council 168 Alliance Party 219, 249 British India Association 13 : by-election 1967 230, 236 British Phosphate Commission 224 : formation of 207 Brown, Doug xix : response to Federation Party Buksh, MS 108 manifesto 235 Buksh, Nabi 40 Amery, Julian 143-144, 161 Buli 47 Amery, LS 41 Bull, PJ 142 Andrews, CF 11, 28, 38 Burns Commission 220 Anthony, James 129 Burns, Sir Alan 184 Archibald, Fred 204 Burton, JW 11, 28 Arya Samaj 12, 33, 37 See also education, bus industry 162 Indian by-election 1967 229-230, 231 : Deo’s influence 109 : Fijian response 237 : elections 1937 49 : results 236-237 : elections 1963 160 : in 1950s elections 111 Cakobau, Ratu Edward xv, 203, 227 : prohibition debate -

A Time Bomb Lies Buried: Fiji's Road to Independence

1. Introduction In his Christmas message to the people of Fiji, Governor Sir Kenneth Maddocks described 1961 as a year of `peaceful progress'.1 The memory of industrial disturbance and a brief period of rioting and looting in Suva in 1959 was fading rapidly.2 The nascent trade union movement, multi-ethnic in character, which had precipitated the strike, was beginning to fracture along racial lines. The leading Fijian chiefs, stunned by the unexpectedly unruly behaviour of their people, warned them against associating with people of other races, emphasising the importance of loyalty to the Crown and respect for law and order.3 The strike in the sugar industry, too, was over. Though not violent in character, the strike had caused much damage to an economy dependent on sugar, it bitterly split the Indo-Fijian community and polarised the political atmosphere.4 A commission of inquiry headed by Sir Malcolm Trustram Eve (later Lord Silsoe) was appointed to investigate the causes of the dispute and to recommend a new contract between the growers, predominantly Indo-Fijians, and the monopoly miller, the Australian Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR). The recommendations of the Burns Commission Ð as it came to be known, after its chairman, the former governor of the Gold Coast (Ghana), Sir Alan Burns Ð into the natural resources and population of Fiji were being scrutinised by the government.5 The construction of roads, bridges, wharves, schools, hospital buildings and water supply schemes was moving apace. The governor had good reason to hope for `peaceful progress'. Rather more difficult was the issue of political reform, but the governor's message announced that constitutional changes would be introduced. -

Sir Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture.Pub

The Sir Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture Third Annual Aviation Industry Conference Week July 2010 W R Tannock BSc (Hons), CEng, FRAeS To be offered the opportunity to deliver the first Sir ber of the New Zealand Territorial Force, left these Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture is indeed an shores for UK, at his own expense, to join the Royal honour and I thank The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Air Force. Although he failed his first medical ex- Navigators, The Royal New Zealand Air Force, The amination - his health was "rundown" after seven Royal Aeronautical Society and The Aviation Indus- weeks at sea - he was soon accepted into the RAF on try Association for inviting me to do so. a short service commission with the rank of Acting Pilot Officer – just as well since he had less than 10 The founding organisations determined that the shillings in its pocket. After the mandatory period of subject of the lecture would be “on any significant " square bashing" and a short period of, as Des Lyn- civilian or military aviation topic, this can include skey used to call it, " knife and fork school", he was design, testing of significant aircraft, significant off to flying training, passing successfully as an technical or safety initiatives or the contributions of "above-average" student graduating with a major civilian or military aviation personnel”. I feel "distinguished pass". it is entirely appropriate that this inaugural lecture should commemorate the life and times of Sir Geof- Geoffrey Roberts was posted to India to fly light- frey himself considering the significant contribution day bombers on the Northwest frontier where he was he made to both military and civil aviation. -

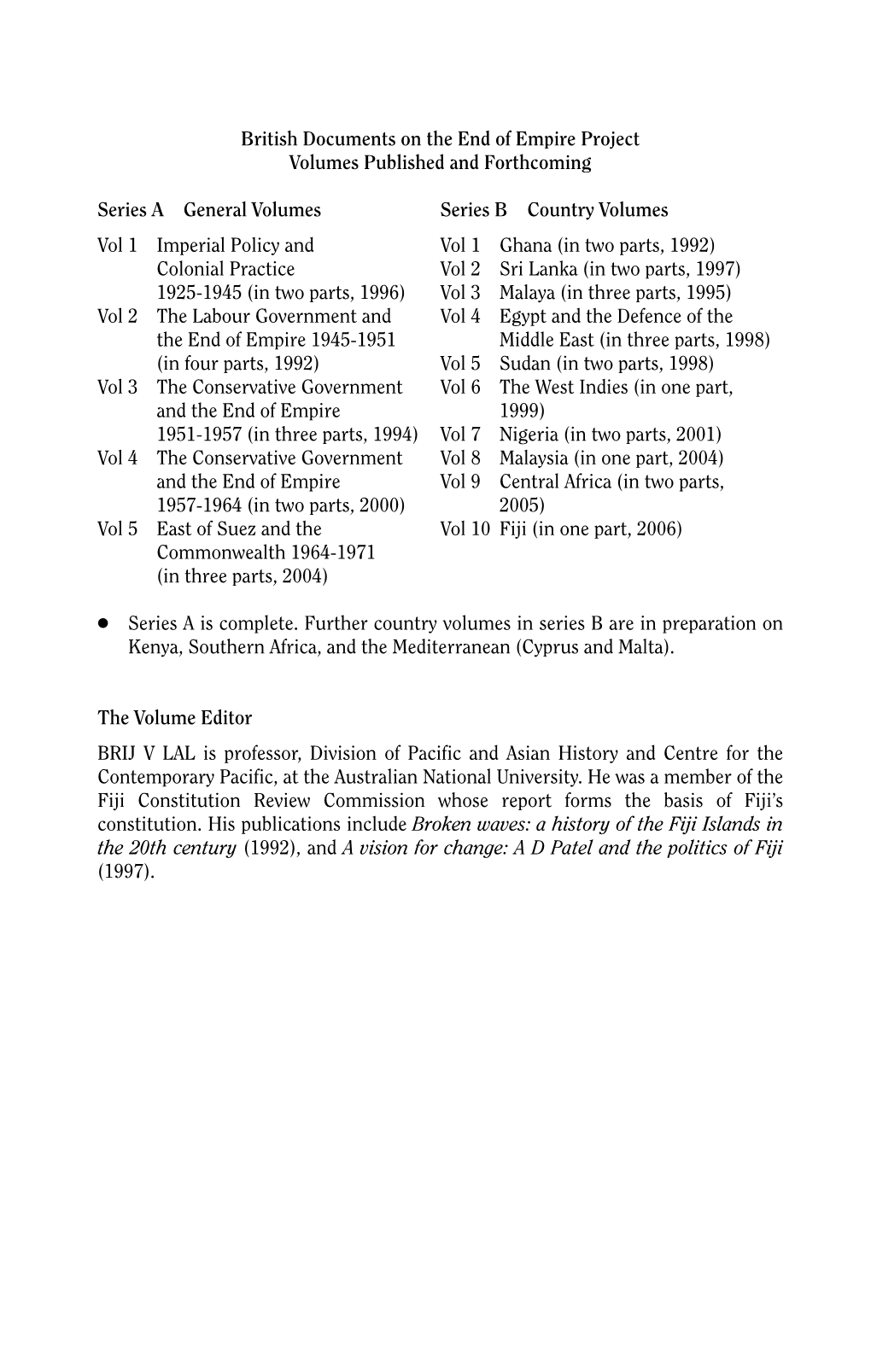

East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (In Three Parts, 2004)

00-Suez-Blurb-pp 21/9/04 11:32 AM Page 1 British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming Series A General Volumes Series B Country Volumes Vol 1 Imperial Policy and Vol 1 Ghana (in two parts, 1992) Colonial Practice Vol 2 Sri Lanka (in two parts, 1997) 1925–1945 (in two parts, 1996) Vol 3 Malaya (in three parts, 1995) Vol 2 The Labour Government and Vol 4 Egypt and the Defence of the the End of Empire 1945–1951 Middle East (in three parts, 1998) (in four parts, 1992) Vol 5 Sudan (in two parts, 1998) Vol 3 The Conservative Government Vol 6 The West Indies (in one part, and the End of Empire 1999) 1951–1957 (in three parts, 1994) Vol 7 Nigeria (in two parts, 2001) Vol 4 The Conservative Government Vol 8 Malaysia (in one part, 2004) and the End of Empire 1957–1964 (in two parts, 2000) Vol 5 East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (in three parts, 2004) ● Series A is complete. Further country volumes in series B are in preparation on Kenya, Central Africa, Southern Africa, the Pacific (Fiji), and the Mediterranean (Cyprus and Malta). The Volume Editors S R ASHTON is Senior Research Fellow and General Editor of the British Documents on the End of Empire Project, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. With S E Stockwell he edited Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice 1925–1945 (BDEEP, 1996), and with David Killingray The West Indies (BDEEP, 1999). Wm ROGER LOUIS is Kerr Professor of English History and Culture and Distinguished Teaching Professor, University of Texas at Austin, USA, and an Honorary Fellow of St Antony’s, Oxford. -

The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 7, No.1, 2012, pp. 135-146 REVIEW ESSAY The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W. David McIntyre Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies Christchurch, New Zealand [email protected] ABSTRACT : This paper reviews the separation of the Ellice Islands from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, in the central Pacific, in 1975: one of the few agreed boundary changes that were made during decolonization. Under the name Tuvalu, the Ellice Group became the world’s fourth smallest state and gained independence in 1978. The Gilbert Islands, (including the Phoenix and Line Islands), became the Republic of Kiribati in 1979. A survey of the tortuous creation of the colony is followed by an analysis of the geographic, ethnic, language, religious, economic, and administrative differences between the groups. When, belatedly, the British began creating representative institutions, the largely Polynesian, Protestant, Ellice people realized they were doomed to permanent minority status while combined with the Micronesian, half-Catholic, Gilbertese. To protect their identity they demanded separation, and the British accepted this after a UN-observed referendum. Keywords: Foreign and Commonwealth Office; Gilbert and Ellis islands; independence; Kiribati; Tuvalu © 2012 Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Context The age of imperialism saw most of the world divided up by colonial powers that drew arbitrary lines on maps to designate their properties. The age of decolonization involved the assumption of sovereign independence by these, often artificial, creations. Tuvalu, in the central Pacific, lying roughly half-way between Australia and Hawaii, is a rare exception. -

History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji SANJAY RAMESH MA (RESEARCH) CENTRE FOR PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2010 Abstract The thesis analyses inter-group conflict in Fiji within the framework of inter-group theory, popularised by Gordon Allport, who argued that inter-group conflict arises out of inter-group prejudice, which is historically constructed and sustained by dominant groups. Furthermore, Allport hypothesised that there are three attributes of violence: structural and institutional violence in the form of discrimination, organised violence and extropunitive violence in the form of in-group solidarity. Using history as a method, I analyse the history of inter-group conflict in Fiji from 1960 to 2006. I argue that inter- group conflict in Fiji led to the institutionalisation of discrimination against Indo-Fijians in 1987 and this escalated into organised violence in 2000. Inter-group tensions peaked in Fiji during the 2006 general elections as ethnic groups rallied behind their own communal constituencies as a show of in-group solidarity and produced an electoral outcome that made multiparty governance stipulated by the multiracial 1997 Constitution impossible. Using Allport’s recommendations on mitigating inter-group conflict in divided communities, the thesis proposes a three-pronged approach to inter-group conciliation in Fiji, based on implementing national identity, truth and reconciliation and legislative reforms. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is dedicated to the Indo-Fijians in rural Fiji who suffered physical violence in the aftermath of the May 2000 nationalist coup. -

Chiefly Leadership in Fiji After the 2014 Elections Stephanie Lawson

3 Chiefly leadership in Fiji after the 2014 elections Stephanie Lawson ‘Chiefdoms are highly variable, but they are all about power.’ (Earle 2011, p. 27) Introduction The last quarter century has seen a significant decline of chiefly influence in Fiji’s politics, albeit with some periods of enhanced status for the paramount symbol of indigenous Fijian traditionalism, the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC). This body, however, was abolished by decree under the military regime of Commodore Josaia Voreqe (Frank) Bainimarama in March 2012. The September 2014 elections held prospects for the restoration of chiefly authority and the role of traditionalism through the Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA) led by Ro Teimumu Vuikaba Kepa, holder of a prominent chiefly title. A victory by SODELPA would also have seen the restoration of the GCC. With SODELPA’s resounding defeat by Bainimarama’s FijiFirst Party, such prospects have received a significant blow. This chapter provides an account of chiefly leadership in national politics, beginning with a survey of Fiji’s colonisation, the role of chiefs in the British colonial regime generally, and their domination 41 THE PEOPLE Have SPOKEN of national politics up until 1987. The second section reviews the political dynamics surrounding chiefly leadership from 1987 until the Bainimarama-led coup of 2006. The final sections examine chiefly involvement in national politics in the lead-up to the 2014 elections and prospects for the future of traditional chiefly political leadership which, given the results, look somewhat bleak. British colonialism and chiefly rule In contrast with many other parts of the world, where colonial rule was imposed by force, the paramount chiefs of Fiji petitioned the British to establish a Crown Colony. -

C:\Users\User\Desktop\Dr Hasan Colgis\Kertas Kerja\MOHD FO'ad

Politics of Accommodation, Power Sharing and Consociational Democracy Dr. Mohd Foad Sakdan Dr. Oemar Hamdan Political of Accommodation The concept of accommodation refers to pragmatic solution to divisive conflicts by abandoning the principles of unilateral majority decisions and including representatives of the main group in the organs of government and decision marking. The political of accommodation is based mainly on a recognition of the need for political stability, and not necessarily on a recognition in principle of the right of all group in society to participation, representation and equal status. Therefore, the more societal and political a particular group has, the more willingness there will be to consider it as a partner to the politics of accommodation.1 The political potential of a group is not determined exclusively or even mainly by its electoral achievements or even its coalition bargaining position. Other important factors are recognition of the legitimacy of the value and interests represented by group and acceptance of the group as part of the social and cultural consensus. Meanwhile, political stability in the country has been attributed to the political system that could be called `an elite accommodation model' or `consociational model' in which each ethnic community is unified under a leadership that can authoritatively bargain for the interests of that community. The leaders of each community, in turn, have the capacity to secure compliance and legitimacy for the bargains that are reached by elite negotiations. Under such circumstances, there exists sufficient trust and empathy among the elite to be sensitive to the most vital concerns of other ethnic communities. -

Intercolonial Convention, 1883

(No. 3.) . 1883. SESSION II. TASMAN I A. LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. INTERCOLONIAL CONVENTION, 1883: REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS. Laid upon the Table by Mr. Moore, and ordered by the Council to be printed,. _18 December, l 883. - • I 1888. NEW SOUTH WALES. INTERCOLONIAL CONVENTION, 1883. REPQRT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERCOLONIAL. CONVENTION, . HELD IN SYDNEY, IN NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER, 1883. 1. MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS. 2. CORRESPONDENCE LAID BEFORE THE CONVENTION. 3. P .A.PERS LAID BEFORE THE CONVENTION. f:lYDNEY : THO~AS RICHARDS, GOVERN~1ENT PRINTElt. 1883. * 831- ,_ MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF TIIE INTERCOLONIAL c·oNVENTION, 1'883) HELD IN SYDNEY, NOVEMBEBr-DEOEMBER, 1883. At the Colonial Secretary's Office, Sydney. 28th NOVEMBER, 1883 . .(First Day.) THE undermentioned_ Gentlemen, Representatives of the Colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, New Zealand, Tasmania, and Western Australia were present, and handed in their Commissions, which having been read, it was resolved that their substance should be published. New Sontli Wales: THE HoNORABLE ALEXANDER STUART, M.P., Premier ancl I Colonial Secretary. THE HoNORABLE GEORGE RICHARD DrnBs, M.P., Colonial Treasurer. THE HoNORABLE WILLIAM BEDE DALLEY, Q.C., M.L.C., A ttorney-_General. New Zeceland : THE HoNORABLE MAJOR HARRY ALmmT ATKINSON, M.P., Premier and Colonial Treasurer. THE HoNoRABLE ]'mmERICK WrrrTAKER, M.L.C., late Premier and Attorney-General. 'Queensland: TrrE HoNORABLE SAllIUEL WALKER GRIFr'ITIT, Q.C., M.P., Premier and Colonial Secretary. _ T1rn HoNORABLE JAMES FRANCIS GARRICK, Q.C., nf.L.C., Postmaster General. Soutli Australia : THE HoNoRABLE JOHN Cox BRAY, M.P., Premier and Chief Secretary. -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1929

THfe AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL CARACAS, VENEZUELA Entrance to Washington Building, in which the American Consulate is located Vol. VI DECEMBER, 1929 No. 12 BANKING AND INVESTMENT SERVICE THROUGHOUT THE WORLD The National City Bank of New York and Affiliated Institutions THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK CAPITAL, SURPLUS AND UNDIVIDED PROFITS $238,516,930.08 (AS OF OCTOBER 4, 1929) HEAD OFFICE THIRTY-SIX BRANCHES IN 56 WALL STREET. NEW YORK GREATER NEW YORK Foreign Branches in ARGENTINA . BELGIUM . BRAZIL . CHILE . CHINA . COLOMBIA . CUBA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC . ENGLAND . INDIA . ITALY . JAPAN . MEXICO . PERU . PORTO RICO REPUBLIC OF PANAMA . STRAITS SETTLEMENTS . URUGUAY . VENEZUELA. THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK (FRANCE) S. A. Paris 41 BOULEVARD HAUSSMANN 44 AVENUE DES CHAMPS ELYSEES Nice: 6 JARDIN du Roi ALBERT ler INTERNATIONAL BANKING CORPORATION (OWNED BY THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK Foreign and Domestic Branches in UNITED STATES . PHILIPPINE ISLANDS . SPAIN . ENGLAND and Representatives in The National City Bank Chinese Branches. BANQUE NATIONALE DE LA REPUBLIQUE D’HAITI . (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: PORT AU-PRINCE, HAITI CITY BANK FARMERS TRUST COMPANY {formerly The farmers* Loan and Trust Company—now affiliated with The National City Bank of New York) Head Office: 22 WILLIAM STREET, NEW YORK Temporary Headquarters: 45 EXCHANGE PLACE THE NATIONAL CITY COMPANY (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) HEAD OFFICE OFFICES IN SO LEADING 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK AMERICAN CITIES Foreign Offices: LONDON . AMSTERDAM . COPENHAGEN . GENEVA . TOKIO . SHANGHAI Canadian Offices: MONTREAL . -

Pacific Entomologist 1925-1966

RECOLLEcnONS OF A Pacific Entomologist 1925-1966 WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR R.W. Paine Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 1994 The Australian Centre for Intemational Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of Ihe Australian Parliament. lis primary mandate is 10 help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special competence. Where trade names ore used this does not constitute endorsement of nar discrimination against any product by the Centre. This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or malerial deemed relevant 10 ACIAR's research and development objectives. The series is distributed intemationally, with an emphasis on developing countries. © Australian Centre for Intemational Agricultural Research GPO Box 157 t Conberra, Australia 2601 . Paine, R.w. 1994. Recollections of a Pacific Entomologist 1925 - 1966. ACIAR Monograph No 27. 120pp. ISBN 1 86320 106 8 Technical editing and production: Arowang Information Bureau Ply Ltd. Canberra Cover: BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra in association with Arawang Information Bureau Ply Lld Printed by The Craftsman Press Ply Ltd. Burwood, Victoria. ACIAR acknowledges the generous support of tihe Paine family in the compilation of this book. Long before agricultural 1920s was already at the Foreword sustainability entered forefront of world biological common parlance, or hazards control activities. Many of the associated with misuse of projects studied by Ron Paine pesticides captured headlines, and his colleagues are touched environmentally friendly on in his delightful and biological control of introduced evocative reminiscences. -

Colonial Administration Records (Migrated Archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021 Most of these files date from the late 1940s participation of Basotho soldiers in the Second Constitutional development and politics to the early 1960s, as the British government World War. There is included a large group of considered the future constitution of Basutoland, files concerning the medicine murders/liretlo FCO 141/294-295: Constitutional reform in although there is also some earlier material. Many which occurred in Basutoland during the late Basutoland (1953-59) – of them concern constitutional developments 1940s and 1950s, and their relation to political concerns the development of during the 1950s, including the establishment and administrative change. For research already representative government of a legislative assembly in the late 1950s and undertaken on this area see: Colin Murray and through the establishment of a the legislative election in 1960. Many of the files Peter Sanders, Medicine Murder in Colonial Lesotho legislative assembly. concern constitutional development. There is (Edinburgh UP 2005). also substantial material on the Chief designate FCO 141/318: Basutoland Constitutional Constantine Bereng Seeiso and the role of the http://www.history.ukzn.ac.za/files/sempapers/ Commission; attitude of Basutoland British authorities in his education and their Murray2004.pdf Congress Party (1962); concerns promotion of him as Chief designate. relations with South Africa. The Resident Commisioners of Basutoland from At the same time, the British government 1945 to 1966 were: Charles Arden-Clarke (1942-46), FCO 141/320: Constitutional Review Commission considered the incorporation of Basutoland into Aubrey Thompson (1947-51), Edwin Arrowsmith (1961-1962); discussion of form South Africa, a position which became increasingly (1951-55), Alan Chaplin (1955-61) and Alexander of constitution leading up to less tenable as the Nationalist Party consolidated Giles (1961-66).