Session 611 Fire Behavior Ppt Instructor Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making Dave Dodson teaches the art of reading smoke. This is an important skill since fighting fires in the year 2006 and beyond will be unlike the fires we fought in the 1900’s. Composites, lightweight construction, engineered structures, and unusual fuels will cause hostile fires to burn hotter, faster, and less predictable. Concept #1: “Smoke” is FUEL! Firefighters use the term “smoke” when addressing the solids, aerosols, and gases being produced by the hostile fire. Soot, dust, and fibers make up the solids. Aerosols are suspended liquids such as water, trace acids, and hydrocarbons (oil). Gases are numerous in smoke – mass quantities of Carbon Monoxide lead the list. Concept #2: The Fuels have changed: The contents and structural elements being burned are of LOWER MASS than previous decades. These materials are also more synthetic than ever. Concept #3: The Fuels have triggers There are “Triggers” for Hostile Fire Events. Flash point triggers a smoke explosion. Fire Point triggers rapid fire spread, ignition temperature triggers auto ignition, Backdraft, and Flashover. Hostile fire events (know the warning signs): Flashover: The classic American Version of a Flashover is the simultaneous ignition of fuels within a compartment due to reflective radiant heat – the “box” is heat saturated and can’t absorb any more. The British use the term Flashover to describe any ignition of the smoke cloud within a structure. Signs: Turbulent smoke, rollover, and auto-ignition outside the box. Backdraft: A “true” backdraft occurs when oxygen is introduced into an O2 deficient environment that is charged with gases (pressurized) at or above their ignition temperature. -

Fire Extinguisher Booklet

NY Fire Consultants, Inc. NY Fire Safety Institute 481 Eighth Avenue, Suite 618 New York, NY 10001 (212) 239 9051 (212) 239 9052 fax Fire Extinguisher Training The Fire Triangle In order to understand how fire extinguishers work, you need to understand some characteristics of fire. Four things must be present at the same time in order to produce fire: 1. Enough oxygen to sustain combustion, 2. Enough heat to raise the material to its ignition temperature, 3. Some sort of fuel or combustible material, and 4. The chemical, exothermic reaction that is fire. Oxygen, heat, and fuel are frequently referred to as the "fire triangle." Add in the fourth element, the chemical reaction, and you actually have a fire "tetrahedron." The important thing to remember is: take any of these four things away, and you will not have a fire or the fire will be extinguished. Essentially, fire extinguishers put out fire by taking away one or more elements of the fire triangle/tetrahedron. Fire safety, at its most basic, is based upon the principle of keeping fuel sources and ignition sources separate Not all fires are the same, and they are classified according to the type of fuel that is burning. If you use the wrong type of fire extinguisher on the wrong class of fire, you can, in fact, make matters worse. It is therefore very important to understand the four different fire classifications. Class A - Wood, paper, cloth, trash, plastics Solid combustible materials that are not metals. (Class A fires generally leave an Ash.) Class B - Flammable liquids: gasoline, oil, grease, acetone Any non-metal in a liquid state, on fire. -

Wildland Firefighter Smoke Exposure

❑ United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Firefighter Smoke Exposure EST SERVIC FOR E Forest National Technology & 1351 1803 October 2013 D E E P R A U RTMENT OF AGRICULT Service Development Program 5100—Fire Management Wildland Firefighter Smoke Exposure By George Broyles Fire Project Leader Information contained in this document has been developed for the guidance of employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, its contractors, and cooperating Federal and State agencies. The USDA Forest Service assumes no responsibility for the interpretation or use of this information by other than its own employees. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official evaluation, conclusion, recommendation, endorsement, or approval of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Ash Pit Burn Injuries

Event Type: Ash Pit Burn Injuries Date: Mid-Late August 2019 Fire Season Location: Southcentral Alaska “The normal season-ending rains that have arrived over Alaska’s Interior have yet to materialize over Southcentral Alaska and the Kenai Peninsula. The weather forecast for the next several days shows that, aside from some isolated rain showers, no widespread steady rains are expected.” Eric Stevens, Fire Meteorologist Alaska Interagency Coordination Center Drought Code indices for Southcentral Alaska on August 23, 2019. Introduction The 2019 fire season in Southcentral Alaska has been unusually dry and the area is experiencing extreme to severe drought. Drought indices are at or above historic highs which has allowed fuels to dry to a substantial depth. Fires in the area are burning deep into organic layers in the ground, creating hazardous ash pits that have caused burn injuries to several firefighters. Historically, Southcentral Alaska has experienced similar ash pit issues in 1996 (Millers Reach Fire) and 2015 (Sockeye Fire). The combination of deep duff and organic soils with drought conditions creates an environment for fires to burn deep into the ground and create ash pits that may be more hazardous than those encountered in other areas of the state. Other contributing factors include ground material being disturbed from home site improvement, agriculture and wind rows. The depth and heat trapped within some ash pits has taken firefighters by surprise. Firefighters may not recognize the hazard associated with these areas. The Swan Lake and McKinley fires have reported multiple ash pit-related burn injuries. 1 Swan Lake Fire Located on the Kenai Peninsula Northeast of Sterling, Alaska A two-person saw team from an IHC crew was performing hazard tree mitigation on this fire when the swamper stepped into an 18-inch-deep ash pit while trying to move a bucked log. -

Fireboats and Search and Rescue Boats with a Small Firegigting

The United States has a long history of fire departments using surplus property from other government agencies , re purposing property within departments, and sometimes other agencies reusing obsolete fire apparatus. Fireboats and Search and Rescue Boats have been converted from military and other government agencies surplus since the end of World War I. It is unlikely there will be any future conversions of large high gallon per minute capacity, 5,000 gpm or more, fireboats from surplus craft . It is possible that some of the tractor tugs built for the U.S. Navy with substantial fire fighting features and capability included could be made available through the Federal Government surplus property transfer programs in a few decades. Large fireboats have since the 1970s been built using features from tugboats, but have many special design features to deal with hazardous materials etc. Search and Rescue and small fireboats of no more the 2,000 or so gallons per minute are still sometimes converted from surplus craft obtained from other government agencies. In 1921, the Baltimore City Fire Department received, by loan from the U.S. Navy, the 110 foot long anti-submarine warfare vessel SC 428 . Ship was built between 1917-and 1919 . Boat was loaned for the purpose of conversion into a fireboat. The ship, renamed Cascade in 1949, served the fire department until 1960. The city received titled to the ship in 1949 through legislation passed by the House and Senate and signed by President Truman. The U.S. Army built several 98 foot tugboat type workboats ,in the early 20th century, to assist with maintaining coastal defense minefields. -

Meet the Seattle Fire Boat Crew the Seattle Fire Department Has a Special Type of Fire Engine

L to R: Gregory Anderson, Richard Chester, Aaron Hedrick, Richard Rush Meet the Seattle fire boat crew The Seattle Fire Department has a special type of fire engine. This engine is a fire boat named Leschi. The Leschi fire boat does the same things a fire engine does, but on the water. The firefighters who work on the Leschi fire boat help people who are sick or hurt. They also put out fires and rescue people. There are four jobs for firefighters to do on the fire boat. The Pilot drives the boat. The Engineer makes sure the engines keep running. The Officer is in charge. Then there are the Deckhands. Engineer Chester says, “The deckhand is one of the hardest jobs on the fire boat”. The deckhands have to be able to do everyone’s job. Firefighter Anderson is a deckhand on the Leschi Fireboat. He even knows how to dive under water! Firefighter Anderson says, “We have a big job to do. We work together to get the job done.” The whole boat crew works together as a special team. The firefighters who work on the fire boat practice water safety all the time. They have special life jackets that look like bright red coats. Officer Hedrick says, “We wear life jackets any time we are on the boat”. The firefighters who work on the fire boat want kids to know that it is important to be safe around the water. Officer Hedrick says, “Kids should always wear their life jackets on boats.” Fishing for Safety The firefighters are using binoculars and scuba gear to find safe stuff under water. -

Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Summer 2016 Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Laura, "Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting" (2016). Graduate Theses & Non-Theses. 90. http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch/90 This Non-Thesis Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses & Non-Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting by Laura Walker A report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Industrial Hygiene Distance Learning / Professional Track Montana Tech of the University of Montana 2016 This page intentionally left blank. 1 Abstract Annually about 100 firefighters die in the line duty, in the United States. Firefighters know it is a hazardous occupation. Firefighters know the only way to reduce the number of deaths is to change the way the firefighter (FF) operates. Changing the way a firefighter operates starts by utilizing traditional industrial hygiene tactics, anticipating, recognizing, evaluating and controlling the hazard. Basic information and history of the fire service is necessary to evaluate FF hazards. An electronic survey was distributed to FFs. The first question was, “What are the health and safety risks of a firefighter?” Hypothetically heart attacks and new style construction would rise to the top of the survey data. -

Prescribed Fire: the Fuels Component

FORESTRY Prescribed Fire: The Fuels Component ► In this second of a four-part series, you will learn the importance of the fuel component in prescribed fire. A common science experiment in grade school is to light a candle, place a glass jar over the candle, and watch the flame go out as the oxygen is consumed. This demonstrates the fire triangle of heat, oxygen, and fuel (figure 1). A prescribed fire is a working example of the principles of the fire triangle. In conducting a prescribed fire, you are either working to move a fire across the land or working to extinguish a fire. In either case, good fire lines are critical for containing the fire within a specific area (figure 2). Fire lines remove the fuel side of the fire triangle. Without the fuel, there is no heat and the fire goes out. Figure 1. The three components needed for a fire to occur are oxygen, heat, and fuel. These make up what is called the fire triangle. Remove one of the Fuel Components sides from this triangle and a fire cannot occur or will be extinguished. The way a fire burns depends on a number of Fuel Volume characteristics of the fuel. An often forgotten component The volume of fuel in the area affects the behavior of is the predominant species of the fuel. Not all grasses the fire and the amount of smoke it produces. Large burn the same; neither do all hardwood leaves or even volumes of fuel pose a significant risk for creating a pine needles. -

Colorado Fire Commission Recommendation 20-01

COLORADO FIRE COMMISSION RECOMMENDATION 20-01 Implement the Colorado Coordinated Regional Mutual Aid System (CCRMAS) Statutory Duties: Per 24-33.5-1233(4)(b)(VI) The Commission will strengthen regional and statewide coordination of mutual aid resources and initial attack capabilities for fires and other hazards. Assumptions: 1. Rapidly expanding incidents can overwhelm the resources of the local fire department and surrounding agencies. 2. Local mutual aid plans exist but there is limited coordination across regions to activate additional resources quickly during rapidly expanding incidents. 3. Decreasing activation time can help minimize the impacts of an incident. 4. During the initial stages of an incident, dispatch centers, and local first responders will be focused on their primary response duties and unable to assist with coordinating rapid mutual aid mobilization. Emergency managers and emergency operations centers will be in the process of being stood up in support of extended response should it become necessary and in preparation for consequence management of subsequent impacts of the emergency response. 5. The statewide coordinated regional mutual aid system covers the time between the start of an incident and when adequate resources arrive for prolonged response through interagency systems and/or local and state Emergency Operations Centers. 6. The goal is to develop a unified approach to mobilizing fire and EMS resources, eliminate redundancy, and eliminate duplicate orders with the end goal of integration into the state response system. 7. A statewide coordinated regional mutual aid system, with dedicated resources for implementation, will help with the coordination and movement of mutual aid resources without impacting local dispatch centers which are busy managing 911 calls and resource response. -

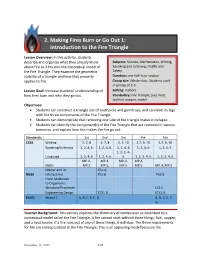

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle.