Recorded by the School of Scottish Studies…’ the Impact of the Tape-Recorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the Deer, Is in the Wood: Chronotopic Identities, Trajectories of Texts and Community Self-Management

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the deer, is in the wood: chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management. Applied Linguistics Review, (doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0134). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/201608/ Deposited on: 24 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Tom Bartlett Time, the deer, is in the wood: Chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management Abstract: This paper opens with a problematisation of the notion of real-time in discourse analysis – dissected, as it is, as if time unfolded in a linear and regular procession at the speed of speech. To illustrate this point, the author combines Hasan’s concept of “relevant context” with Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope to provide an analysis of Sorley MacLean’s poem Hallaig, with its deep-rootedness in space and its dissolution of time. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to following the poem’s metamorphoses and trajectory as it intertwines with Bartlett’s own life and family history, creating a layered simultaneity of meanings orienting to multiple semio-historic centres. In this way the author (pers. comm.) “sets out to illustrate in theory, text analysis and (self-)history the trajectories taken by texts as they cross through time and space; their interconnectedness -

Sheila Stewart

Sheila, Belle and Jane Turriff. Photo: Alistair Chafer “…Where would Sheila Stewart the ballad singing Scottish Traveller, Traditional Singer and Storyteller tradition in Scotland 1935 - 2014 be today without the unbroken continuity by Pete Shepheard of tradition passed on to us by Sheila and other members of Scotland’s ancient Traveller community…” “…one of Scotland’s finest traditional singers, inheriting The family was first brought to When berry time comes roond look for the Stewarts who rented Traveller lore and balladry from all light by Blairgowrie journalist each year, Blair’s population’s berry fields at the Standing Stones sides of her family, and learning a rich oral culture Maurice Fleming in 1954 following swellin, at Essendy. So he cycled up to songs from her mother, some of a chance meeting with folklorist There’s every kind o picker there Essendy and it was Sheila Stewart the most interesting, and oldest, of songs, ballads Hamish Henderson in Edinburgh. and every kind o dwellin; he met (just 18 years old at the songs in her repertoire came from Discovering that Hamish had There’s tents and huts and time) who immediately said she Belle’s brother, her uncle, Donald caravans, there’s bothies and and folk tales that recently been appointed as a knew the song and told Maurice MacGregor, who carefully taught there’s bivvies, research fellow at the School it had been written by her mother her the ballads. Donald could had survived as And shelters made wi tattie-bags Belle. Maurice reported the of Scottish Studies, Maurice neither read nor write, but was an and dug-outs made wi divvies. -

QH 40Th Anniversary Press Release

EMBARGOED TILL 5/11/18 at midday THE QUEEN’S HALL – LIFE BEGINS AT 40 1979-2019: Former church celebrates 40 years of welcoming music worshippers through its doors Southside of the Tracks 12.01.19 Steven Osborne & Alban Gerhardt 06.07.19 The Queen’s Hall enters its fortieth year in 2019 with a packed and varied programme of high quality events which reflect the wealth of entertainment it has provided audiences over the years, whilst also looking forward to a bright future. The celebrations start on 12 January with a who’s who of singer-songwriters brought together on the same stage for the first time by Scotland’s foremost fiddle player, John McCusker. Renowned for his skill at transcending musical boundaries, John has shared stages with Paul Weller, Paolo Nutini and Teenage Fanclub and has been a member of Mark Knopfler’s house band since 2008. In Southside of the Tracks: 40 years of traditional music at The Queen’s Hall he will perform with his chosen house band of James Mackintosh, Ian Carr, Ewen Vernal, Michael McGoldrick and Louis Abbott (Admiral Fallow) with special guests, so far, Roddy Woomble (Idlewild), Kathleen MacInnes, Phil Cunningham, Adam Holmes, Daoiri Farrell, Heidi Talbot and Rachel Sermanni. More guests are to be announced. Nigel Griffiths, Chair of The Queen’s Hall Board of Trustees says, “We’re starting our fortieth year as we mean to go on and have a bold and ambitious programme which reflects the calibre of artists performing on our stage. In the face of developing competition it is so important for Edinburgh, as the capital city, to keep this beloved institution on the map and I believe we’re now poised to enter a truly dynamic era in The Queen’s Hall’s history.” To commemorate the concert on 6 July 1979 when The Queen’s Hall was officially opened by HM Queen Elizabeth II, we have multi-award-winning Scottish pianist Steven Osborne with one of the world’s finest cellists Alban Gerhardt performing a programme of Schumann, Brahms, De falla, Debussy and Ravel. -

The Musicians______

The musicians_______________________________________________________________________ Ross Ainslie Bagpipes & Whistle Ross hails from Bridge of Earn in Perthshire. He began playing chanter at the age of 8 and like Ali Hutton studied under the watchful eye of the late great Gordon Duncan and was a member of the Vale of Atholl pipe band. Ross also plays with Salsa Celtica, Dougie Maclean's band, India Alba, Tunebook, Charlie Mckerron's trio and in a duo with Irish piper Jarlath Henderson. He released his début solo album "Wide Open" in 2013 which was voted 9th out of 50 in the Sunday Herald "The Scottish albums of 2013". He was nominated for "musician of the year" at the Radio 2 folk awards 2013 and also for "Best Instrumentalist" at the Scots Trad Music Awards in 2010 and 2012. Ali Hutton Bagpipes & Whistle Ali, from Methven in Perthshire, was inspired at the age of 7 to take up the bagpipes and came up through the ranks at the Vale of Atholl pipe band. He was taught alongside Ross Ainslie by the late, great Gordon Duncan and has gone on to become a successful multi‐instrumentalist on the Scottish music scene. He has produced and co‐produced several albums such as Treacherous Orchestra’s “Origins”, Maeve Mackinnon's “Don't sing love songs”, The Long Notes’ “In the Shadow of Stromboli” and Old Blind Dogs’ “Wherever Yet May Be”. Ali is also currently a member of Old Blind Dogs and the Ross Ainslie band but has played with Capercaillie, Deaf Shepherd, Emily Smith Band, Dougie Maclean, Back of the Moon and Brolum amongst many others. -

Speaker Biogs

Friday 4th December 2014 MAC Arts, Galashiels Speaker Biogs James Mackintosh – CABN Advocate for Music James is an experienced touring and session musician, composer and teacher; equally at home on the road, in the recording studio and on the film set. He is a founding member of groundbreaking Scottish group Shooglenifty, touring globally for over 20 years, playing concerts and festivals in New Zealand, Australia, Europe, USA, Canada and Asia. He is co founder of label "Shoogle Records". He has extensive teaching and workshop experience in drums, percussion and group work and has hosted workshops at concerts and festivals around the globe, from Seattle to Sydney. As one of CABN’s Advocates, James designs and delivers support for the music sector through advice sessions and events covering topics relevant to music professionals. Tom Bancroft – Musician, Drummer, Managing Director at ABC Creative Music Tom Bancroft is a drummer, composer, bandleader and educator. Once a Cambridge educated medical doctor Tom now makes his living from music. He has played with musicians ranging from Sun Ra & Martyn Bennett to Geri Allen and Bill Wells. He has led big band Orchestro Interrupto for more than 20 years and now leads small band Trio Red, as well as being a long term member of Trio AAB and the Dave Milligan Trio. He is a founder member of the Pathhead Music Collective which won the £50,000 Creative Places Award in 2013 for his village where Tom and 14 other professional musicians live and run concerts and education and community projects. Heather MacLeod – Leod Music, Stoneyport Associates, Bevvy Sisters, Loveboat Big Band Originally from the Isle of Lewis, Heather has appeared with many different bands including McFalls Chamber, La Boum! and currently the Bevvy Sisters and the Loveboat Big Band - who have their roots in the much loved Bongo Club. -

BUSINESS BULLETIN No. 156/2014 Monday 3 November 2014

BUSINESS BULLETIN No. 156/2014 Monday 3 November 2014 Summary of Today’s Business Meetings of Committees 2.00 pm Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee Salutation Hotel, Perth For full details of today’s business, see Section A. For full details of the future business, see sections B and C. ___________________________________________________________________ 1 Contents The sections which appear in today‘s Business Bulletin are in bold Section A: Today‘s Business - Meetings of Committees - Meeting of the Parliament Section B: Future Meetings of the Parliament Section C: Future Meetings of Committees Section D: Oral Questions - Questions selected for First Minister‘s Questions - Questions selected for response by Ministers and junior Scottish Ministers at Question Time Section E: Written Questions – new questions for written answer Section F: Motions and Amendments Section G: Bills - New Bills introduced - New amendments to Bills - Members‘ Bills proposals Section H: New Documents – new documents laid before the Parliament and committee reports published Section I: Petitions – new public petitions Section J: Progress of Legislation – progress of Bills and subordinate legislation Section K: Corrections to the Official Report 2 Business Bulletin: Monday 3 November 2014 Section A – Today’s Business Meetings of Committees All meetings take place in the Scottish Parliament, unless otherwise specified. Contact details for Committee Clerks are provided at the end of the Bulletin. Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee 25th Meeting, 2014 The Committee will meet at 2.00 pm in The Salutation Hotel, Perth 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take item 4 in private. 2. Draft Budget Scrutiny 2015-16: The Committee will consider the outcomes of the workshop sessions involving local organisations held before the start of the meeting. -

Paterson, Michael Bennis (2001) Selling Scotland: Towards an Intercultural Approach to Export Marketing Involving Differentiation on the Basis of "Scottishness"

Paterson, Michael Bennis (2001) Selling Scotland: towards an intercultural approach to export marketing involving differentiation on the basis of "Scottishness". PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4495/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Selling Scotland: towards an intercultural approach to export marketing involving differentiation on the basis of "Scottishness" by MICHAEL BENNIS PATERSON School of Scottish Studies (Faculty of Arts) University of Glasgow A thesis submitted to the University of Glasgow in March 2001 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ABSTRACT Selling Scotland towards an intercultural approach to export marketing involving differentiation on the basis of "Scottishness" THIS dissertation examines opportunities for Scottish exporters to differentiate in target markets overseas on the basis of their Scottishness. Findings include: 1. ultimately, identity is largely conferred by others, rather than being shaped by assertions on one's own behalf; 2. definitional experiences of "Scottishness" may frequently be derived from and mediated by determinants that lie outwith Scotland; 3. constructed identifications of key or core Scottish values, by their syncretism, present impoverished views of Scotland; 4. -

St Andrew Highland Gathering

the www.scottishbanner.com Scottishthethethe Australasian EditionBanner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 41 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 41 36 36 Number Number Number 7 11 The11 The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international ScottishScottish Scottish newspapernewspaper newspaper May JanuaryMay 2013 2013 2018 Scotland Let it What’s new for 2018 » Pg 14 snowUS Barcodes Creating snow and boosting the Highland economy »7 Pg25286 16 844598 0 1 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 Band on Australia $4.00; North American $3.00; N.Z. $3.95 2018 - A Year in Piping .......... » Pg 6 Nigel Tranter: the Run Scotland’s Storyteller ........... » Pg 25 Scottish snowdrop’s Playing pipes with - A sign of the season .............. » Pg 29 Robert Burns: Sir Paul McCartney Scotland’s Bard ........................ » Pg 30 » Pg 6 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Scottishthe Volume Banner 41 - Number 7 The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Valerie Cairney January-Celebrating two great Scots Editor Sean Cairney growing up. When Uncle John came however) and the story has crossed to town we all chipped in and helped over into books and a film and surely EDITORIAL STAFF where we could with the shows. It must be considered one of the great Jim Stoddart Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot was only a little later in childhood I stories about ‘man’s best friend’. -

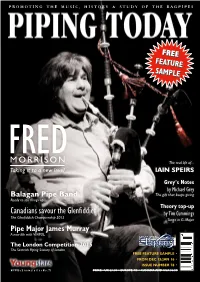

FREE FEATURE SAMPLE Balagan Pipe Band

PROMOTING THE MUSIC, HISTORY & STUDY OF THE BAGPIPES FREEFREE FEATUREFEATURE SAMPLESAMPLE FRED MORRISON The real life of... Taking it to a new level IAIN SPEIRS Grey’s Notes by Michael Grey Balagan Pipe Band The gift that keeps giving Ready to stir things up Theory top-up Canadians savour the Glenfiddich by Tim Cummings The Glenfiddich Championship 2015 Tunes in G-Major Pipe Major James Murray A new life with WAPOL The London Competition 2015 The Scottish Piping Society of London free feature sample • from Dec 15/Jan 16 • Issue number 78 • NYPBoS newsletter No.75 prIce - uK £3.30 • europe 5 • canaDa anD usa $6.50 contents Editorial 5 Roddy MacLeod News 6 Fred Morrison 8 Taking it to a new level Balagan Pipe Band 14 FRONT COVER PICTURE: Ready to stir things up Fred Morrison in concert at Celtic Connections 2012 by John Slavin. See feature on pages 8-13. Theory Top-Up by Tim Cummings 21 Tunes in G-Major Brothers on the bagpipes 22 Sons of the Most Holy Reedemer Youngstars Newsletter No.75 23 Q&A with Calum Craib Canadians savour the Glenfiddich 28 Glenfiddich Piping Championship 2015 New life and opportunities at WAPOL 34 Pipe Major James Murray Iain Speirs 36 The real life of... The London Competition 2015 40 The Scottish Piping Society of London Competition League for Amateur Solo Pipers 43 10 questions with Sean Moloney Product Reviews 44 New CD reviews Grey’s Notes by Michael Grey 46 The gift that keeps giving www.thepipingcentre.co.uk EDITOR: Roddy MacLeod MBE, BSc • FEATURES MANAGER: John Slavin • PUBLISHER: © The National Piping Centre 2015 CORRESPONDENCE: The National Piping Centre, 30-34 McPhater Street, Glasgow, Scotland. -

Musica Scotica Retroproceedings MASTER

Hearing Heritage Selected essays on Scotland’s music from Musica Scotica conferences ! Edited by M. J. Grant Published by the Musica Scotica Trust, 2020 All texts © Te authors, 2020 Images included in this volume appear by permission of the named copyright holders. Tis volume is freely available to download, in line with our mission to promote scholarship and knowledge exchange. Further distribution, including of excerpts, is subject to this being credited appropriately. ISBN 0-9548865-9-3 Glasgow: Musica Scotica Trust, 2020 Table of Contents About the Authors Gordon Munro & Introduction 1 M. J. Grant Hugh Cheape Raising the Tone: Te Bagpipe and the Baroque 3 Joshua Dickson A Response to ‘MacLeod’s Controversy’: Further 19 Evidence of the Pibroch Echo Beat’s Basis in Gaelic Song Elizabeth C. Ford Te Crathes Castle Flute: Artistic License or Historical 31 Anomaly? John Purser James Oswald (1710–1769) and Highland Music: 39 Context and Legacy Per Ahlander Te Seal Woman: A Celtic Folk Opera by Marjory 55 Kennedy-Fraser and Granville Bantock Stuart Eydmann & Seeking Héloïse Russell-Fergusson 73 Hélène Witcher Marie Saunders We’re All Global Citizens Now, and Yet … 84 About the authors Per G. L. Ahlander read modern languages, musicology, opera theatre and fne arts at Stockholm University, music at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music and is a graduate of the Stockholm School of Economics. He completed his doctorate in 2009 at the University of Edinburgh, where he subsequently held postdoctoral research fellowships at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and the Department of Celtic & Scotish Studies. -

Matthew Mcvarish Awarded

Company of Donors / SPRING 2015 rcs.ac.uk Coming up... BBC Radio 3: Poulenc 50 Years On with Pascal Rogé Fri 17 April / 1pm / Stevenson Hall Pascal Rogé exemplifies the finest in French pianism, characterised by its elegance, beauty and refined phrasing. With a recording output covering the great French repertoire, it is a pleasure to have him here to conclude this series of lunchtime recitals for BBC Radio 3, celebrating the distinctive music of Francis Poulenc. Crerar Hotels Trust Plug Festival Tue 5 – Fri 8 May supports the Our festival of new music from RCS composers is a celebration of potential. Guest artists at this year’s festival include: Ilya Gringolts and Sinae Junior Conservatoire Lee, the Red Note Ensemble, Glasgow New Music Expedition and Drake Music Scotland. rerar Hotels Trust has generously donated and pursue their dreams by studying their chosen £4000 to the Junior Conservatoire performing art form at the highest level”. Opera Bus Cof Drama. Director of Drama, Dance, Production and Screen Hugh Hodgart was Chief Executive of Crerar Hotels and Chairman Wed 13 May / New Athenaeum presented a special cheque at Crerar Loch Fyne of Crerar Hotels Trust Paddy Crerar said The RCS Opera department completes its Hotel and Spa in Inveraray in February. supporting the development of the younger operatic/Shakespearean Merry Wives/Falstaff generation is a core value of the trust. ‘trilogy’ with Vaughan Williams’ colourful and The donation will be used as a scholarship fund lyrical Sir John in Love. Travelling between to benefit talented Scottish students between the “Investment in the future of young Scottish Charlotte Square in Edinburgh and RCS in ages of 14-18 who face financial barriers in their individuals is key to all of our futures…To help Glasgow by luxury coach, the Opera Bus makes education and skills development.