James Francis Warren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 01 March 22.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER 22 March 2014 21 Jumadal I 1435 - Volume 19 Number 5611 Price: QR2 ON SATURDAY Missing plane’s debris may never be found LONDON: Even if the two unidentified objects shown on satellite images floating in the southern Indian Ocean are debris from the missing Malaysia Airlines plane, finding them could prove to be a long and difficult process that may rely on luck as much as on advanced technology, oceanographers and aviation experts have warned. If the objects are recovered, locating the rest of the Boeing 777 on the ocean floor could turn out to be harder still. And if the remains can eventually be pieced together, working out exactly what happened to flight MH370 may be the toughest job of all. See also page 11 Doha Theatre Festival opens at Katara DOHA: The Minister of Culture, Arts and Heritage H E Dr. Hamad bin Abdul Aziz Al Kuwari yesterday opened Doha Theatre Festival at Katara Drama Theatre. In his speech, the minister said many events in the theatrical field will be held in the com- ing days, including workshops and an contest in playwriting, and a forum for playwrights in Qatar which will be held in the last week of April every year. He said work was under way to create an electronic library for theatre documentation, and admission to the theatre studies programme will be announced soon in collaboration with the Community College in Doha. The programme will result in an applied science degree in the field of theatre. EU prepares for trade Debating war with Russia BRUSSELS: Europe began to prepare for a possible trade war with Russia over Ukraine yesterday, with the EU executive in Brussels ordered to draft plans for much more sub- stantive sanctions against Moscow if Vladimir Putin presses ahead with Russian territorial expansion. -

Downloaded File

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348870739 Mga Elementong Katutubo at Pakahulugan sa mga Pananagisag sa Nagcarlan Underground Cemetery, Nagcarlan, Laguna Article · December 2020 CITATIONS READS 0 2,383 1 author: Axle Christien Tugano University of the Philippines Los Baños 35 PUBLICATIONS 16 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Axle Christien Tugano on 17 April 2021. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Mga Elementong Katutubo at Pakahulugan sa mga Pananagisag sa Nagcarlan Underground Cemetery, Nagcarlan, Laguna1 Axle Christien TUGANO Asian Center, University of the Philippines - Diliman [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4849-4965 ABSTRAK Marami sa mga simbahan (iglesia) at libingan (cementerio) ang itinayo noong panahon ng mga Español sa dati nang sinasambahan at nililibingan ng mga katutubo, kung kaya bahagi pa rin ng pagtatawid sa sinaunang pananampalataya patungo sa tinatawag na Kristiyanismong Bayan (tinatawag ng iilan bilang Folk Catholicism o Folk Christianity). Dahil hindi pasibong tinanggap ng mga katutubo ang ipinakikilalang dogma, inangkop nila sa kanilang kinab7ihasnang kultura ang pagtanggap sa Kristiyanismo. Makikita ang ganitong pag-angkop sa sistema ng paniniwala; iba’t ibang tradisyon; at konsepto ng mga bagay-bagay. Ipinamalas din nila ang bersiyon ng pagsasama o sinkretismo sa sining ng arkitektura na makikita sa mga imprastraktura katulad ng cementerio. Isa ang Nagcarlan Underground Cemetery (NUC) ng Nagcarlan, Laguna sa mga tinitingnan bilang halimbawa ng isang magandang cementerio sa Pilipinas na tumutugon sa pamantayang binanggit sa itaas. Sa kabila ng imprastraktura at arkitekturang banyaga nito, mababakas pa rin ang patuloy na pagdaloy ng mga elementong pangkalinangan ng mga katutubo sa pamamagitan ng mga simbolong nakamarka at makikita sa kabuuan ng libingan. -

Kuwait Police Nab Shooting Suspects

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, MARCH 22, 2014 JAMADA ALAWWAL 21, 1435 AH No: 16112 Kuwait Army Walking the India beat Lieutenant tightrope to Pakistan by dies as lorry, survive in 7 wickets car collide4 Mumbai13 in43 Twenty20 Kuwait police nab shooting suspects Max 27º 150 Fils ‘Awaited Mahdi’ in police net Min 17º By Hanan Al-Saadoun vant authorities on charges of possession of arms and opening fire. The ministry KUWAIT: Kuwait security forces have warned that it would not allow the recur- arrested 11 suspects for firing weapons in rence of such deadly and illegal activities Taima and Sulaibiya areas. The arrests fol- and the security forces would deal firmly lowed massive raids in the areas. These sus- with any violator. pects have been charged with opening fire in Sulaibiya and Taima districts. They were ‘Awaited Mahdi’ nabbed after the security operatives In another development, a Saudi expat tracked them down in Sulaibiyah area. The denied that he attacked his mother who suspects include 11 bedoons-Mansoor accused him of attempting to kill her. He in Fahad, Fahad Enad, Bader Essa, Khalaif turn described her as arrogant and consid- Samran, Essa Samran, Adel Samran, ered himself the “awaited Mahdi.” The Mohammad Samran, Hussein Ali, Sami Ajaj, Saudi, 24, was arrested in Jahra on charges Mohammad Al-Shimmari, Dhaher Aryan; of attempted murder. When he was ques- two Syrians Salem Al-Enezi and Abdallah tioned about the charges he said “this is Al-Enezi and a Kuwaiti Rabah Khalid. not true, this one (point at his mother) is Some firearms, pistol, bullets and drugs arrogant, and I am the ‘awaited Mahdi’ who were also confiscated during the raids. -

Lenten Mission at South Church

F r r a i AVKBAfMD D AILt UIBUUIATIUN sting o f Manebeatar Dr. C. J. Sin, prasidaot a t tba bean compleled and promise to pre the New Testament and the Life of were dassmatss together and br- for ths Msatk s ( Marck. i9S9 Orange w&1 be held^ondayheld Mon evening Cbrlatiaa University at Foochow, sent a week of high spiritual liu^ri- Christ and has a rsputatlon for be MONSCNOR JOBN NEAU dalned to the priesthood about, tbs at 8 o’clock at the home o f Mr. and China, will speak and show motion LENTEN MISSION ration. Beginning Monday evening, ing an impressive speaker, aa well w m s time. MOnaigiior Neals rs- Mrs. Roy B. Warren of 673 Wood- pictures of "Rural ’ Ife In South April 8 and continuing through F ri aa a great teacher. Ha wrlll endea- ceived many honors and decorations b ild n street for the purpose o f re- China," at the Lenten lastituto at day evening the 12th, at 7:30 vor to lead In an exploration of the FRIEND OF REf.McCANN 5 . 4 9 9 Center church parish ball Sunday o’clock,- Prof. Alexander Purdy of resources o f our Christian faith and for his scboUrly attainments direct ■ *sr s( HM AU8K oalvlng appUutiona. AT SOUTH CHURCH from tbs Vatican, including tbs Pw - di----- at 6 o’clock. Special music will be Hartford Seminary foundation wrlll deepen the appreciation - of what rsM ol CIrwilsilews furnished by the church choir and toral cross and ring. ) Jarvis OtoTt Danea Hall. -

Ang Epikseryeng Filipino: Diskurso Sa Amaya

Ang Epikseryeng Filipino: Diskurso sa Amaya Ateneo de Naga University Vasil A.Victoria, Ph.D aiba sa mga nakamihasnan, nakasanayan at nakagawiang mga soap opera, soap operang nakabahag at epikserye ang tawag sa Amaya. Ito ang kauna-unahang panuring o bansag sa ganitong uri ng dugtungang palabas sa telebisyon. Ano nga ba ang epikserye? Higit na malalim na tanong, paano masasabing epikseryengK Filipino ang isang palabas? Bago tuluyang masagot ang mga tanong na nailatag, mahalagang taluntunin ang naging kasaysayan at anyo ng mga soap opera sa mga palabas- pantelebisyon. Sa disertasyon ni Reyes (1) kaniyang sinabi na isa ang soap Victoria... opera sa mga programang sinusundan ng mga manonood ng telebisyon. At dahil kinahuhumalingan ang mga ganitong klaseng programa, unti-unti na itong sinusundan hanggang sa makabuo na ng mga solidong tagapagtangkilik. May isang aspekto ang masasabing naging dahilan kung bakit ganoon na lamang ang naging tugon ng mga tao sa mga programang kanilang sinusundan. Bukod sa katotohanang may mga elemento ng pag-iidolo sa mga artista kung saan masasabing tunay na naggagandahang lalaki at babae ang mga bida, pumapasok din ang kapangyarihan ng wika bilang mekanismo ng pagkakaunawa at pagkahumaling. Tumutukoy ang soap opera sa mga dramang pantelebisyon na may sumusunod na pormulasyon, (1) problem (suliranin), (2) examination (pagtalakay sa suliranin), (3) catharsis (pamamaraan upang magupo ang suliranin) at (4) resolution (ang kasagutan o kaliwanagan sa suliranin). Ibinatay ang siklong nabanggit sa narrative drama ayon kay Aristotle. Tinawag naman itong soap sapagkat karaniwan, mga sabon ang nagiging pangunahing advertiser nito (Anger, 1999). Mula sa soap opera, nabuo naman ang taguring telenobela. -

Haras La Pasioì N

ÍNDICE ESTADÍSTICAS ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES ESTADÍSTICAS BLACK TYPE DESTACADOS 2016 GANADORES CLÁSICOS REFERENCIA DE PADRILLOS EASING ALONG MANIPULATOR ZENSATIONAL SIDNEY’S CANDY SIXTIES ICON VIOLENCE LIZARD ISLAND NOT FOR SALE EMPEROR RICHARD ROMAN RULER KEY DEPUTY POTRILLOS 1 Liso Y Llano Easing Along - Potra Liss por Potrillon 2 Giradisco Easing Along - Gincana por Lode 3 Portofinense Easing Along - Prolongada por Tiznow 4 Mikonos Grand Easing Along - Magic Sale por Not For Sale 5 Infobae Easing Along - Idyllic por Halo Sunshine 6 Anime Easing Along - Abide por Pivotal 7 Vuemont Easing Along - Valentini por Boston Harbor 8 Gingerland Easing Along - Gone For Christmas por Gone West 9 Illegallo Easing Along - Illegally Blonde por Southern Halo ÍNDICE 10 Santinesi Easing Along - Santita por Maria’s Mon 11 Buen Gusto BO Easing Along - Buena Alegria por Interprete 12 Falabello Not For Sale - Fancy Tale por Rahy 13 Fashion Kid Not For Sale - Fashion Model por Rainbow Quest 14 Grecko Not For Sale - Grecian por Equalize 15 EL Viruta Not For Sale - La Impaciente por Bernstein 16 Scandalous Not For Sale - Sa Torreta por Southern Halo 17 American Tattoo Not For Sale - American Whisper por Quiet American 18 Paco Meralgo Not For Sale - Potential Filly por Thunder Gulch 19 Palpito Fuerte Not For Sale - Palpitacion por Thunder Gulch 20 Sale Tinder Not For Sale - Smashing Glory por Honour And Glory 21 Onagro Not For Sale - Orientada por Grand Slam 22 Emotividad Not For Sale - Embrida por Lizard Island 23 Verso DE Amor Not For Sale - Stormy Venturada -

College Surplus Often Placed for Auction GIRLS B’BALL CLASS ADDED Official Says College’S Surplus List

OKLAHOMA CITY COMMUNITY COLLEGE INSIDE PIONEER ONLINE To comment on stories or to access the latest news, features, multimedia, online exclusives and JUNEIONEER 13, 2014 PIONEER.OCCC.EDU COVERING OCCC SINCE 1978 updates, visit pioneer. occc.edu. P Gone fishin’ EDITORIAL MINIMUM WAGE INCREASE NECESSARY Online Editor Siali Siaosi says too many people are forced to work multiple part- time jobs instead of one good-paying, full- time job. Read more. OPINION, p. 2 NEWS HONOR ROLL RECIPIENTS LISTED Students who made the President’s and Vice President’s Honor Rolls will be notified by mail the week of June 21. JOHN HUYNH/PIONEER Look inside to see if Western Heights High School students Jonathan and Adam Thomas fish at the OCCC retention pond on campus June 2. you made it. Catch and release is the only method of authorized fishing in the pond, located on the northeast corner of campus. NEWS, p. 6 & 7 SPORTS College surplus often placed for auction GIRLS B’BALL CLASS ADDED Official says college’s surplus list. Items on mon surplus item. cess involved in surplusing a TO ROSTER computers most the list that aren’t able to be “All surplus computer equip- computer, he said. Basketball used elsewhere in the college ment first goes to our [Informa- “They trickle down comput- Fundamentals has common items may then be listed for sale on tion Technology] department ers. So, department A gets a been added to the a government online auction and they have the power to new computer that may be two College for Kids BRYCE MCELHANEY site called Public Surplus and determine what is no longer or three years old and it goes lineup this summer. -

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017 A Publication of the Harvard University Herbaria Including The Journal of the Arnold Arboretum Arnold Arboretum Botanical Museum Farlow Herbarium Gray Herbarium Oakes Ames Orchid Herbarium ISSN: 1938-2944 Harvard Papers in Botany Initiated in 1989 Harvard Papers in Botany is a refereed journal that welcomes longer monographic and floristic accounts of plants and fungi, as well as papers concerning economic botany, systematic botany, molecular phylogenetics, the history of botany, and relevant and significant bibliographies, as well as book reviews. Harvard Papers in Botany is open to all who wish to contribute. Instructions for Authors http://huh.harvard.edu/pages/manuscript-preparation Manuscript Submission Manuscripts, including tables and figures, should be submitted via email to [email protected]. The text should be in a major word-processing program in either Microsoft Windows, Apple Macintosh, or a compatible format. Authors should include a submission checklist available at http://huh.harvard.edu/files/herbaria/files/submission-checklist.pdf Availability of Current and Back Issues Harvard Papers in Botany publishes two numbers per year, in June and December. The two numbers of volume 18, 2013 comprised the last issue distributed in printed form. Starting with volume 19, 2014, Harvard Papers in Botany became an electronic serial. It is available by subscription from volume 10, 2005 to the present via BioOne (http://www.bioone. org/). The content of the current issue is freely available at the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries website (http://huh. harvard.edu/pdf-downloads). The content of back issues is also available from JSTOR (http://www.jstor.org/) volume 1, 1989 through volume 12, 2007 with a five-year moving wall. -

Attorneys for Epstein Guards Wary of Their Clients Being Singled out For

VOLUME 262—NO. 103 $4.00 WWW. NYLJ.COM TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2019 Serving the Bench and Bar Since 1888 ©2019 ALM MEDIA PROPERTIES, LLC. COURT OF APPEALS IN BRIEF Chinese Professor’s hearing date of Dec. 3. She also NY Highest Court Judges Spar IP Fraud Case Reassigned mentioned that the payments were coming from a defendant A third judge in the Eastern in the case discussed in the Over How to Define the Word District of New York is now sealed relatedness motion. handling the case of a Chinese While the Curcio question ‘Act’ in Disability Benefits Case citizen accused of stealing an now moves to Chen’s court- American company’s intellec- room, Donnelly issued her tual property on behalf of the order Monday on the related- Office by Patricia Walsh, who was Chinese telecom giant Huawei, ness motion. BY DAN M. CLARK injured when an inmate acciden- according to orders filed Mon- “I have reviewed the Govern- tally fell on her while exiting a day. ment’s letter motion and con- JUDGES on the New York Court of transport van. Walsh broke the CRAIG RUTTLE/AP U.S. District Judge Pamela clude that the cases are not Appeals sparred Monday over how inmate’s fall and ended up with Chen of the Eastern District of presumptively related,” she the word “act,” as in action, should damage to her rotator cuff, cervi- Tova Noel, center, a federal jail guard responsible for monitoring Jeffrey Epstein New York was assigned the case wrote. “Indeed, the Government be defined in relation to an injured cal spine, and back. -

Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines

Table of Contents Chapter 1 Philippine Regions ...................................................................................................................................... Chapter 2 Philippine Visa............................................................................................................................................. Chapter 3 Philippine Culture........................................................................................................................................ Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines.............................................................................................................................. Chapter 5 Health & Wellness in the Philippines........................................................................................................... Chapter 6 Philippines Transportation........................................................................................................................... Chapter 7 Philippines Dating – Marriage..................................................................................................................... Chapter 8 Making a Living (Working & Investing) .................................................................................................... Chapter 9 Philippine Real Estate.................................................................................................................................. Chapter 10 Retiring in the Philippines........................................................................................................................... -

REGIONAL REPORT on the APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No. 10

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No. 10 May 2019 Date No. Company Name and Address Project Name Project Owner Approved LEXAND CONSTRUCTION & 1 INSTALLATION OF 25 UNITS DOUBLE ARM LGU-TANGCUB CITY, DEVELOPMENT 5/2/2019 ELECTRICAL POST AT TAN AVENUE MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL Banadero, Ozamiz City LEXAND CONSTRUCTION & 2 INSTALLATION OF 25 UNITS DOUBLE ARM ROUND LGU-TANGCUB CITY, DEVELOPMENT 5/2/2019 STEEL ELECTRICAL POST AT BARANGAY STA. CRUZ MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL Banadero, Ozamiz City J.M LACORTE CONSTRUCTION 3 PROPOSED 2 CLASSROOM SCHOOL BUILDING AT PROVINCE OF MISAMIS P-17 Tanguile St. Poblacion Bayugan 5/2/2019 KALAGONOY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, GINGOOG CITY ORIENTAL City DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND 19KC0080-RESURFACING OF UNPAVED ROAD D2J BUILDERS VENTURE HIGHWAYS REGION X SHOULDERS ALONG BARANDIAS-DOMINOROG ROAD 4 BLOCK 11 LOT 15 SILVER CREEK BUKIDNON 3RD JCT.MARADUGAO-CAMP KIBARITAN-DOMINOROG 5/6/2019 SUBDIVISION DISTRICT ENGINEERING ROAD AND MARAMAG MARADUGAO CARMEN CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY OFFICE DICKLUM, ROAD,PANGANTUCAN AND KALILANGAN , BUKIDNON MANOLO FORTICH BUKIDNON MEGAKONSTRUK DEVELOPMENT 5 18K00335-REPAIR/MAINTENANCE OF DWPH BUILDING VOLUNTEERISM ST., FICCOVILLE DPWH-REGION X 5/6/2019 OLD QAHD BUILDING SUBD OPOL, MISAMIS ORIENTAL HANSIE CORPORATION Unit 303 Victoria Towers C. Timog NGCP-NATIONAL GRID 6 ONSHORE PORTION OF THE MINDANAO Avenue Corner CORPORATION IN THE 5/6/2019 SUBSTATION UPGRADING PROJECT Panay Avenue, Brgy Paligsahan PHILIPPINES Quezon City BENEFORTE D. TAN MALLACK/ADMIN 7 BENEFORTE D. TAN B-4, L-386 R.E.R Kauswagan, PROPOSED RESIDENTIAL/ COMMERCIAL BUILDING 5/7/2019 MALLACK Cagayan De Oro City KIOKONG CONSTRUCTION & 8 DEVELOPMENT CORP. -

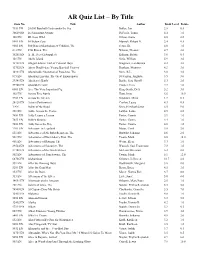

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

AR Quiz List – By Title Quiz No. Title Author Book Level Points 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue DePaola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8001 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert N. 2.4 0.5 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 16201 EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) Kalman, Bobbie 3.6 0.5 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3.0 13701 EN Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 4.2 3.0 13702 EN Abner Doubleday: Young Baseball Pioneer Dunham, Montrew 4.2 3.0 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Pasadena, The Stine, R.L. 3.0 3.0 815 EN Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator Stevenson, Augusta 3.5 3.0 29341 EN Abraham's Battle Banks, Sara Harrell 5.3 2.0 39788 EN Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 2.7 1.0 6001 EN Ace: The Very Important Pig King-Smith, Dick 5.2 3.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 6.6 10.0 7201 EN Across the Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 1.7 0.5 28128 EN Actors (Performers) Conlon, Laura 4.3 0.5 1 EN Adam of the Road Gray, Elizabeth Janet 6.5 9.0 301 EN Addie Across the Prairie Lawlor, Laurie 4.9 4.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7701 EN Adventure in Legoland Matas, Carol 3.8 2.0 451 EN Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein, The Hurwitz, Johanna 4.6 2.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 401 EN Adventures of Ratman, The Weiss, Ellen 3.3 1.0 29524 EN Adventures of Sojourner, The Wunsch, Susi Trautmann 7.8 1.0 21748 EN Adventures of the Greek Heroes McLean/Wiseman 6.2 4.0 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 68706 EN Afghanistan Gritzner, Jeffrey A.