Love in the Age of Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Issue in PDF Format

Editors' Notes Asterisms - fiction by Heidi Vornbrock Roosa Melody and Soil - poetry by Joseph Murphy A History of Lies - fiction by Sarah Kuntz Jones Two Poems - by Robert S. King The Companion - fiction by Mary Pat Musick Lilium Lophophorum - poetry by Michael Meyerhofer The Subatomic Search Engine - fiction by Andre Medrano A Reluctant Enthusiast - nonfiction by Amy Takabori Three Poems - by Kim Garcia Contributors' Notes Book Reviews Fifty-for-Fifty Contest for Readers Guidelines for Submissions Questions for Reader Group Discussion Previous Issues The Summerset Review Page 2 of 66 Some of the work we received for consideration in this issue had a distinct, logistical characteristic. Over the course of a few weeks in the spring, there was an onslaught of submissions appearing in our inbox from students of Brigham Young University. How this came to be, we don't know. Perhaps an influencial graduate student was behind it all? Or maybe an English professor there singled out The Summerset Review for some odd, beautiful reason, and assigned the class a project to send literary work our way? In reviewing the submissions, we were impressed, and we're happy to publish one of them in this issue, a nonfiction piece by an undergraduate, Amy Takabori, titled "A Reluctant Enthusiast," her first publication. We want to thank all those at BYU who tried us, and warm appreciation goes to the person who inspired all of this, whoever you are. Our Lit Pick of the Quarter this time is set inside a Catholic high school. Found in Blue Mesa Review, Issue #23, Spring 2010, the story is written by Steven Ramirez, titled "Judas Didn't Wear Shoes Anyway," where two students, Carlos and Espiridión, dole out the food in the cafeteria during lunch. -

Social Condenser’ in Eldar Ryazanov’S Irony of Fate VOL

ESSAY Soviet Bloc(k) Housing and the Self-Deprecating ‘Social Condenser’ in Eldar Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate VOL. 113 (MARCH 2021) BY LARA OLSZOWSKA A completely atypical story that could happen only and exclusively on New Year's Eve. – Eldar Ryazanov, Irony of Fate, 1976. Zhenya lives in apartment № 12 of unit 25 in the Third Builder Street, and so does Nadia, only that she lives in Leningrad, whereas Zhenya lives in Moscow. After a heavy drinking session at the bathhouse with friends on New Year’s Eve, Zhenya accidentally gets on a flight to Leningrad one of his friends had booked for himself. Still intoxicated on arrival, he gives his address to a taxi driver and arrives “home”. He lets himself into Nadia’s flat with his key – even their locks match – and falls asleep. When Nadia wakes him, the comical love story between the two takes center stage and the coincidence of their matching housing blocks seems to be little more than a funny storytelling device. Upon further examination it is far more significant. The misleading epigraph at the start of Eldar Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate quoted above links the ludicrous events that follow to the date on which they unfold. On New Year’s Day 1976, the film was first broadcast to television audiences across the Soviet Union, telling an extraordinary tale in a very ordinary place. This “atypical story” is not really a result of the magic of New Year’s Eve alone, but more so a product of its setting: a Soviet apartment in a Soviet housing block in a socialist city. -

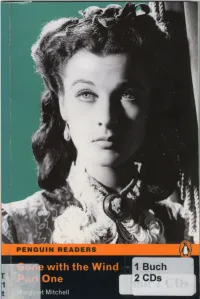

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

CONSIGNES Semaine Du 23 Au 27 Mars Travail À Faire Sur La

CONSIGNES Semaine du 23 au 27 mars Travail à faire sur la thématique des films Pour suivre le cours de cette semaine voici les étapes à suivre : 1- D’abord, vous lisez attentivement la trace écrite en page 2 puis vous la recopiez dans votre cahier. 2- Ensuite, vous compléter au crayon à papier la fiche en page 3. Pour faire cela, vous devez d’abord lire toutes les phrases à trou puis lire chaque proposition et ensuite essayez de compléter les trous. 3- Pour terminer, vous faites votre autocorrection grâce au corrigé qui se trouve en page 4 1 Monday, March 23rd Objectif : Parler des films Film vocabulary I know (vocabulaire de film que je connais) : - film (UK) / movie (USA) - actor = acteur / actress = actrice - a trailer = une bande annonce - a character = un personnage 1. Different types of films - Activity 2 a 1 page 66 (read, listen and translate the film types) An action film = un film d’action / a comedy = une comédie / a drama = un drame / an adventure film = un film d’aventure / an animation film = un film d’animation = un dessin animé / a fantasy film = un film fantastique / a musical = une comédie musicale/ a spy film = un film espionnage / a horror film = un film d’horreur / a science fiction film = un film de science fiction. - Activity 2 a 2 page 66 (listen to the film critic and classify the films) Johnny English Frankenweenie The Hobbit Les Misérables The Star Wars Reborn (French) series - A comedy, - An animation - A fantasy film - a musical - the series are film, science fiction - An action film - an adventure - a drama films and and - A comedy and film - adventure films - A spy film - A horror film 2. -

(500) Days of Summer 2009

(500) Days of Summer 2009 (Sökarna) 1993 [Rec] 2007 ¡Que Viva Mexico! - Leve Mexiko 1979 <---> 1969 …And Justice for All - …och rättvisa åt alla 1979 …tick…tick…tick… - Sheriff i het stad 1970 10 - Blåst på konfekten 1979 10, 000 BC 2008 10 Rillington Place - Stryparen på Rillington Place 1971 101 Dalmatians - 101 dalmatiner 1996 12 Angry Men - 12 edsvurna män 1957 127 Hours 2010 13 Rue Madeleine 1947 1492: Conquest of Paradise - 1492 - Den stora upptäckten 1992 1900 - Novecento 1976 1941 - 1941 - ursäkta, var är Hollywood? 1979 2 Days in Paris - 2 dagar i Paris 2007 20 Million Miles to Earth - 20 miljoner mil till jorden 1957 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - En världsomsegling under havet 1954 2001: A Space Odyssey - År 2001 - ett rymdäventyr 1968 2010 - Year We Make Contact, The - 2010 - året då vi får kontakt 1984 2012 2009 2046 2004 21 grams - 21 gram 2003 25th Hour 2002 28 Days Later - 28 dagar senare 2002 28 Weeks Later - 28 veckor senare 2007 3 Bad Men - 3 dåliga män 1926 3 Godfathers - Flykt genom öknen 1948 3 Idiots 2009 3 Men and a Baby - Tre män och en baby 1987 3:10 to Yuma 2007 3:10 to Yuma - 3:10 till Yuma 1957 300 2006 36th Chamber of Shaolin - Shaolin Master Killer - Shao Lin san shi liu fang 1978 39 Steps, The - De 39 stegen 1935 4 månader, 3 veckor och 2 dagar - 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days 2007 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer - Fantastiska fyran och silversurfaren 2007 42nd Street - 42:a gatan 1933 48 Hrs. -

In the Crowding Darkness by Jeff Augustin

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO in the crowding darkness A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Theatre and Dance (Playwriting) by Jeff Augustin Committee in charge: Naomi Iizuka, Chair Jim Carmody Allan Havis Manuel Rotenberg 2014 The thesis of Jeff Augustin is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To my mom, for carrying me through life. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature page………………………………………………………………….. iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………… iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………. V Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….. vi Abstract of the Thesis……………………………………………………........... vii in the crowding darkness………………………………………………………… 1 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful to all who have supported me throughout my training and thesis process. I would like to thank Dr. Clara Diaz and Carol Cecil for pushing me to pursue the arts. Dr. Luke Jorgensen and Dr. John Houchin for giving me the tools to be a well rounded theatre artist. Dr. Scott Cummings for giving me a voice and literally telling me I should be a writer. For their constant support I would like to thank my colleagues Joshua Brody, David Bruin, Jenna Carino, -

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN the LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist Degree, Belarusian State University

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist degree, Belarusian State University, 2001 Master of Arts, Brock University, 2005 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Olga Klimova It was defended on May 06, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Aleksandr Prokhorov, Associate Professor, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of William and Mary, Virginia Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Olga Klimova 2013 iii SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES Olga Klimova, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The central argument of my dissertation emerges from the idea that genre cinema, exemplified by youth films, became a safe outlet for Soviet filmmakers’ creative energy during the period of so-called “developed socialism.” A growing interest in youth culture and cinema at the time was ignited by a need to express dissatisfaction with the political and social order in the country under the condition of intensified censorship. I analyze different visual and narrative strategies developed by the directors of youth cinema during the Brezhnev period as mechanisms for circumventing ideological control over cultural production. -

Lights, Camera, Action: Romantic Comedies from The

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION: ROMANTIC COMEDIES FROM THE MALE PERSPECTIVE By TERESA TACKETT Bachelor of Arts in Public Relations Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2016 LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION: ROMANTIC COMEDIES FROM THE MALE PERSPECTIVE Thesis Approved: Dr. Danny Shipka Thesis Adviser Dr. Cynthia Nichols Dr. BobbiKay Lewis ii Name: TERESA TACKETT Date of Degree: MAY, 2016 Title of Study: LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION: ROMANTIC COMEDIES FROM THE MALE PERSPECTIVE Major Field: MASS COMMUNICATIONS Abstract: Romantic comedies are cited as the highest-viewed film genre of the twenty-first century, yet there is a lack of academic research concerning film consumers’ attitudes toward the genre and the plausibility of learning and adopting behavior because of romantic content. This thesis addresses those gaps in the literature. A qualitative interview analysis was conducted with ten male film consumers who reported their ideas, opinions and experiences with the top ten highest-grossing romantic comedies from 2009-2015. As a result, five main themes emerged, which are (a) men cite romantic comedies as setting unrealistic expectations for relationships; (b) men are put off by the predictability of the genre; (c) men do not consume the genre with other men; (d) men use romantic comedies as a learning tool; and, (e) men cite drama in relationships as the most relatable aspect of romantic comedies. The data set was rich and descriptive in nature and the qualitative interview analysis supported the advancement of four theories, including Social Cognitive Theory, Cultivation Theory, Third-person Effect Theory and Spiral of Silence Theory. -

978–0–230–30016–3 Copyrighted Material – 978–0–230–30016–3

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–30016–3 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Louis Bayman and Sergio Rigoletto 2013 Individual chapters © Contributors 2013 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–30016–3 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

9781474437257 Refocus The

ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky 66616_Toymentsev.indd616_Toymentsev.indd i 112/01/212/01/21 111:211:21 AAMM ReFocus: The International Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer, Stefanie Van de Peer, and Gary D. Rhodes Board of advisors: Lizelle Bisschoff (University of Glasgow) Stephanie Hemelryck Donald (University of Lincoln) Anna Misiak (Falmouth University) Des O’Rawe (Queen’s University Belfast) ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of international film directors, from the celebrated to the ignored, in direct relationship to their respective culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts—and the broader parameters of international film history and theory. The series provides a forum for introducing a broad spectrum of directors, working in and establishing movements, trends, cycles, and genres including those historical, currently popular, or emergent, and in need of critical assessment or reassessment. It ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or outside of the studio system—beginning with the origins of cinema and up to the present. ReFocus brings these film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Susanne Bier Edited by Missy Molloy, Mimi Nielsen, and Meryl Shriver-Rice ReFocus: The Films of Francis Veber Keith Corson ReFocus: The Films of Jia Zhangke Maureen Turim and Ying Xiao ReFocus: The Films of Xavier Dolan -

The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan A

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers Student Research 4-24-2017 Female Moments / Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan A. Scharaga Ursinus College, [email protected] Adviser: Jennifer Fleeger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_hon Part of the Communication Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Scharaga, Jordan A., "Female Moments / Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies" (2017). Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers. 6. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_hon/6 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media and Communication Studies Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Female Moments/Male Structures: The Representation of Women in Romantic Comedies Jordan Scharaga April 24, 2017 Submitted to the Faculty of Ursinus College in fulfillment of the requirements for Distinguished Honors in the Media and Communication Studies Department. Abstract: Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl again. With this formula it seems that romantic comedies are actually meant for men instead of women. If this is the case, then why do women watch these films? The repetition of female stars like Katharine Hepburn, Doris Day and Meg Ryan in romantic comedies allows audiences to find elements of truth in their characters as they grapple with the input of others in their life choices, combat the anxiety of being single, and prove they are less sexually naïve than society would like to admit. -

Self/Other Representations in Aleksei Balabanov's 'Zeitgeist Movies'

SELF/OTHER REPRESENTATIONS IN ALEKSEI BALABANOV‟S „ZEITGEIST MOVIES‟: FILM GENRE, GENRE FILM AND INTERTEXTUALITY Florian Weinhold School of Languages, Linguistics and Cultures A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2011 2 Contents ABSTRACT……………….……………………………..….............…............... 6 DECLARATION………………………………………………….......................7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT.....……………………………………................. 7 THE AUTHOR...………………………………………………….......................8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………..………....…................... .9 Chapter 1: Introduction..............................………………………......……........11 1.1 Background, Rationale, Aim and Structure of the Introduction…………. 11 1.2 Why Balabanov?…………………………………..…….…….................. 13 1.3 Why Balabanov‟s „Genre Films‟?………………………..………............ 16 1.4 Balabanov‟s Genre Films in Russian and Western Criticism..................... 19 1.5 Contributions of the Study......................………………………………… 28 1.6 Aim, Objectives and Research Questions of the Thesis..............…........... 29 1.7 Primary Sources………….......................................................................... 31 1.8 Structure of the Thesis................................................................................ 32 Chapter 2: Methodology.......................................................................................35 2.1 Introduction...........................………………….......................................... 35 2.2 Why Genre?……………………………………...................……............