Download This Issue in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

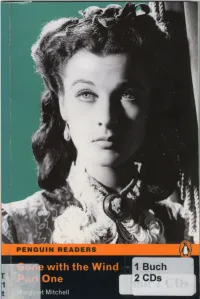

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

In the Crowding Darkness by Jeff Augustin

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO in the crowding darkness A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Theatre and Dance (Playwriting) by Jeff Augustin Committee in charge: Naomi Iizuka, Chair Jim Carmody Allan Havis Manuel Rotenberg 2014 The thesis of Jeff Augustin is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To my mom, for carrying me through life. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature page………………………………………………………………….. iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………… iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………. V Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….. vi Abstract of the Thesis……………………………………………………........... vii in the crowding darkness………………………………………………………… 1 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful to all who have supported me throughout my training and thesis process. I would like to thank Dr. Clara Diaz and Carol Cecil for pushing me to pursue the arts. Dr. Luke Jorgensen and Dr. John Houchin for giving me the tools to be a well rounded theatre artist. Dr. Scott Cummings for giving me a voice and literally telling me I should be a writer. For their constant support I would like to thank my colleagues Joshua Brody, David Bruin, Jenna Carino, -

<^ the Schreiber Times

< ^ The Schreiber Times Vol. XXVIII Paul D. Schreiber High School Wednesday, September 30, 1987 ZANETTI TAKES CHARGE Board Names Guidance Head as Acting Principal by Dave Weintraub When Dr. Frank Banta, Schreiber's principal for eight years, departed at the end (rf the last school year for a different job, he left some large shoes to fill. The school board and Superintendent Dr. William Heebink set out on a search for a new principal over the summer. Many applicants were reviewed, but no one was picked. The board and Dr. Heebink decided to extend the search through the 1987-88 school year. To fill the void Dr. Banta had left, they asked John Zanetti, Chairman of the Guidance Department, to serve as acting principal. He accepted, and was given a ten-month contract, which began in September. Most people who know Mr. Zanetti know him as a soft- spoken and amiable man. He has been in the Port Washington school system for many years, and he had humble beginnings. He started work at Salem School as a physical education teacher in 1958. He stayed there for six years and during that time in- troduced wrestling and lacrosse to the high school. He became the first coach of those teams. After Salem, he taught physical educa- tion at Schreiber for two years. He became a guidance counselor in 1967. He was appointed guidance chairman in 1980. He has now moved to the top of Schreiber's administrative lad- der. Has his transition been smooth? "I have an ulcer," he jokes. "Actually, I think I've ad- justed better than I thought I would. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research and Preservation of These Early Discs. ALL MP3 Files Can Be Sent to You B

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] S.O.S. Band - Finest, The 1983 S.O.S. Band - Just Be Good To Me 1984 S.O.S. Band - Just The Way You Like It 1980 S.O.S. Band - Take Your Time (Do It Right) 1983 S.O.S. Band - Tell Me If You Still Care 1999 S.O.S. Band with UWF All-Stars - Girls Night Out S.O.U.L. - On Top Of The World 1992 S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M. with M. Visage - It's Gonna Be A Love. 1995 Saadiq, Raphael - Ask Of You 1999 Saadiq, Raphael with Q-Tip - Get Involved 1981 Sad Cafe - La-Di-Da 1979 Sad Cafe - Run Home Girl 1996 Sadat X - Hang 'Em High 1937 Saddle Tramps - Hot As I Am 1937 (Voc 3708) Saddler, Janice & Jammers - My Baby's Coming Home To Stay 1993 Sade - Kiss Of Life 1986 Sade - Never As Good As The First Time 1992 Sade - No Ordinary Love 1988 Sade - Paradise 1985 Sade - Smooth Operator 1985 Sade - Sweetest Taboo, The 1985 Sade - Your Love Is King Sadina - It Comes And Goes 1966 Sadler, Barry - A Team 1966 Sadler, Barry - Ballad Of The Green Berets 1960 Safaris - Girl With The Story In Her Eyes 1960 Safaris - Image Of A Girl 1963 Safaris - Kick Out 1988 Sa-Fire - Boy, I've Been Told 1989 Sa-Fire - Gonna Make it 1989 Sa-Fire - I Will Survive 1991 Sa-Fire - Made Up My Mind 1989 Sa-Fire - Thinking Of You 1983 Saga - Flyer, The 1982 Saga - On The Loose 1983 Saga - Wind Him Up 1994 Sagat - (Funk Dat) 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - I'd Rather Leave While I'm In Love 1977 1981 Sager, Carol Bayer - Stronger Than Before 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - You're Moving Out Today 1969 Sagittarius - In My Room 1967 Sagittarius - My World Fell Down 1969 Sagittarius (feat. -

Creating an Audience for Community Theatre: a Case Study of Night of the Living Dead at the Roadhouse Theatre

CREATING AN AUDIENCE FOR COMMUNITY THEATRE: A CASE STUDY OF NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD AT THE ROADHOUSE THEATRE Robert Connick A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2007 Committee: Ron Shields, Advisor Steve Boone Eileen Cherry Chandler © 2007 Robert M. Connick All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor The Roadhouse Theatre for Contemporary Art, located in Erie, Pennsylvania, combines theatre and film as their primary form of artistic development in the Erie community. Through hosting film festivals and adapting film scripts for the stage, the Roadhouse brings cinematic qualities into its theatrical productions in an effort to reach a specific market in Erie. This study focused on the Roadhouse’s production history and highlights one particular work that has developed from there into a production available for national publication and distribution: Lori Allen Ohm’s stage adaptation of Night of the Living Dead. The success of this play provided the Roadhouse with criteria to meet four aspects that Richard Somerset-Ward lists as necessary for successful community theatres. This study examined how Night of the Living Dead developed at the Roadhouse Theatre and the aspects of the script that have made it successful at other theatres across the country. By looking at themes found in the script, I presented an argument for the play’s scholarly relevance. By creating a script with national interest and relevance, Lori Allen Ohm and the Roadhouse Theatre created an historical legacy that established the theatre as one that reached its local audience while also providing something new and worthwhile to American theatre as a whole. -

His Scent of Sandalwood

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 His scent of sandalwood. Lujain Almulla University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Almulla, Lujain, "His scent of sandalwood." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2711. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2711 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIS SCENT OF SANDALWOOD By Lujain Almulla A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2017 HIS SCENT OF SANDALWOOD By Lujain Almulla A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2017 by the Following Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Paul Griner ___________________________________ Ian Stansel ___________________________________ Maryam Moazzen ii ABSTRACT HIS SCENT OF SANDALWOOD Lujain Almulla April 19, 2017 This creative thesis is a collection of fictional stories, connected by a common geographical and cultural thread: Kuwait. The stories unravel across a span of four thousand years. The poetic-prose style of the opening vignette is a nod to the earliest form of writing that makes up the bulk of Kuwait’s literature: poetry. -

Love in the Age of Communism

STOCKHOLMS UNIVERSITET MKI / Vt. 2006 Filmvetenskapliga institutionen Handledare: Anu Koivunen LOVE IN THE AGE OF COMMUNISM Soviet romantic comedy in the 1970s MK-uppsats framlagd av Julia Skott Titel: Love in the age of communism; Soviet romantic comedy in the 1970s Författare: Julia Skott Institution: Filmvetenskapliga institutionen, Stockholms universitet Handledare: Anu Koivunen Nivå: Magisterkurs 1 Framlagd: Vt. 2006 Abstract: The author discusses three Soviet comedies from the 1970s: Moskva slezam ne verit (Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, Vladimir Menshov, 1979), Osenniy marafon (Autumn Marathon, Georgi Daneliya, 1979), and Ironiya Sudby, ili S lyogkim parom (Irony of Fate, Eldar Ryazanov, 1975), and how they relate to both conventions of romance and conventions of the mainstream traditions of the romantic comedy genre. The text explores the evolution of the genre and accompanying theoretic writings, and relates them to the Soviet films, focusing largely on the conventions that can be grouped under an idea of the romantic chronotope. The discussion includes the conventions of chance and fate, of the wrong partner, the happy ending, the temporary and carnevalesque nature of romance, multiple levels of discourse, and some aspects of gender, class and power. In addition, some attention is paid to the ways in which the films connect to specific genre cycles, such as screwball comedy and comedy of remarriage, and to the implications that a communist system may have on the possibilities of love and romance. The author argues that Soviet and Hollywood films share many conventions of romance, but for differing reasons. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------- p. 1 Concepts; method; previous scholarship – p. -

Timothy Findley's

TIMOTHY FINDLEY’S THEWARS season sponsor title sponsor Supporting the arts, locally. Each year, through various donations and sponsorships, we are committed to helping our local communities. We’re proud to be the 2018/2019 season sponsor of the Grand Theatre. 18-1626 The Grand Theatre_Ev2.indd 1 20/08/2018 12:06:49 PM WELCOME In 2001, I directed the premiere of The Trials of Ezra Pound by Timothy Findley at the Stratford Festival. I was immensely honoured, excited, and terrified to have the opportunity to work alongside the renowned playwright and novelist. Rehearsing that play was one of the highlights of my life. Tiff (as we were to call him) attended most rehearsals. He never failed to encourage or applaud our efforts. My terror quickly disap- peared due to his kindness and generosity — his supportive laughter was intoxicating. We continued on with another project the following summer and were in mid-development when he died rather suddenly. At the time, I remember feeling that I was not ready or willing to stop working with this colleague turned friend. It was then that the idea for a stage version of The Wars was born. A few years later, we premiered the play in Calgary and Vancouver. Forty years ago, Tiff wrote this courageous story of a young Canadian going off to war. As I began writing the adaptation, I was drawn to the eloquent way in which Tiff reminds us of the cost of war and all the pain that it causes. As I con- tinued to write, my focus turned to the idea of heroism. -

Monday, May K, 196K ROUND-UP

k, 6 t Monday, May 19 k -2- Number Fifty Four ROUND-UP GEORGE KLEIN WHBQ MEMPHIS TENN LARRY LEE WABB MOBILE ALABAMA Chapel Of Love-Dixie Cups (RB) PICKS Try To Find Yourself-Righteous Brothers Suspicion-Terry Stafford (Cru) SALES Wish Someone-Irma Thomas (imp) / (Moo) Ain’t Gonna Kiss Ya-Searchers (Kap) CALLS Bits And Pieces-Dave Clark Five (Epi) What*d I Say-Elvis Presley (RCA.) COMER Cold At Night-Nita Hill (Cir) LARRY PATE WAPX MONTGOMERY ALABAMA JOHNNY BEE WACL WAYCROSS GEORGIA I ’ll Find You-Valerie & Nick (Glo) PICKS My Love Is True-George Hughley (Gay) Bits And Pieces-Dave Clark Five (Epi) SALES Chapel Of Love-Dixie Cups (RB) Wish Someone-Irma Thomas (imp) CALLS Wrong For Each Other-Andy Williams (Col) In My Tenement-Clyde Me Phatter (Mer) COMER Burning Memories-Ray Price (Col) DEAN GRIFFITH WPGC WASHINGTON DC LARRY HART KOTN PINE BLUFF ARKANSAS Donnie-Bermudas (Era) PICKS New Orleans-Bern Elliott (*) Love Me Do-Beatles (Tol) SALES Thank You Girl-Beatles (Vj) P S/Love Me Do-Beatles (Tol) CALLS P S I Love You-Beatles (Tol) Ain’t That Just Like Me-Searchers (Kap) COMER Every Little Bit-Brenda Holloway (Tam) SKIP WILKERSON WTIX NEW ORLEANS LA LARRY THOMPSON KOBE PORT ARTHUR TEXAS World Without Love-Peter & Gordon (Cap) PICKS Chapel Of Love-Dixie Cups (RB) Wish Someone-Irma Thomas (imp) SALES Blue Diamond-Gene Summers (Cap) Gypsy Woman-Eddie Powers ( - ) CALLS I ’m So Proud-Impressions (ABC) Walk On By-Dionne Warwick (See) COMER Wee Wee Hours-James Brown (Kin) JOHNNY ANGEL WHSL WILMINGTON NC PAT HUGHES WQXI ATLANTA GEORGIA Do You Love -

All the Things I've Been Richard Helmling University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 All the Things I've Been Richard Helmling University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Helmling, Richard, "All the Things I've Been" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2498. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2498 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL THE THINGS I’VE BEEN A NOVEL RICHARD HELMLING Department of Creative Writing APPROVED: Jeffrey Sirkin, Ph.D., Chair Daniel Chacon, MFA Jonna Perrillo, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Richard Helmling 2010 Dedication For Claudia, who survived it. “The love story is the tribute the lover must pay to the world in order to be reconciled with it.” -The Lover’s Discourse Roland Barthes ALL THE THINGS I’VE BEEN by RICHARD HELMLING, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2010 Acknowledgements I want to extend my thanks to all my peers in the MFA program at UTEP and online across the globe who have helped me grow as a writer during my time studying alongside them. -

Adventures of a Former Girlfriend: a Novel Colleen Helen Fava Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Adventures of a Former Girlfriend: A Novel Colleen Helen Fava Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Fava, Colleen Helen, "Adventures of a Former Girlfriend: A Novel" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVENTURES OF A FORMER GIRLFRIEND: A NOVEL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of English by Colleen H. Fava B.A., New Jersey City University, 1999 May 2005 Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. iv Chapter 1: The Split………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 2: Corn Blocker.……………………………………………………………………………. 13 Chapter 3: Original Split…………………………………………………………………………. 25 Chapter 4: The Morning After…………………………………………………………………. 28 Chapter 5: TGIF……………….…………………………………………………………………………………. 46 Chapter 6: Bar Scenes……………………………………………………………………………………. 52 Chapter 7: -

The Other Side of Me

THE OTHER SIDE OF ME THE OTHER SIDE OF ME Copyright © 2005 by Sidney Sheldon Family Limited Partnership All rights reserved. Warner Books Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com. ISBN: 0-7595-6729-8 First eBook Edition: August 2006 For my beloved granddaughters, Lizy and Rebecca so that they will know what a magical journey I had THE OTHER SIDE OF ME “He that has no fools, knaves nor beggars in his family was begot by a flash of lightning.” —Thomas Fuller 17th century English clergyman CHAPTER 1 t the age of seventeen, working as a delivery boy at Afremow’s drugstore in Chicago was the perfect job, Abecause it made it possible for me to steal enough sleeping pills to commit suicide. I was not certain exactly how many pills I would need, so I arbitrarily decided on twenty, and I was careful to pocket only a few at a time so as not to arouse the suspicion of our pharmacist. I had read that whiskey and sleeping pills were a deadly com- bination, and I intended to mix them, to make sure I would die. It was Saturday—the Saturday I had been waiting for. My parents would be away for the weekend and my brother, Richard, was staying at a friend’s. Our apartment would be deserted, so there would be no one there to in- terfere with my plan. At six o’clock, the pharmacist called out, “Closing time.” He had no idea how right he was.