EUFOR RCA: Tough Start, Smooth End by Thierry Tardy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power-Hungry Are Fueling Violence in the Central African Republic

Note: This is the English translation of an op-ed in French that originally appeared in Le Monde and was written by Enough Project Analyst and Researcher, Nathalia Dukhan. The power-hungry are fueling violence in the Central African Republic By Nathalia Dukhan August 21, 2017 Fourteen armed factions, a multitude of local militia groups, invasions by mercenaries from neighboring countries, and a militia army — in August 2017, less than a year after the official retreat of the French military operation, Sangaris, this is the situation confronting the Central African Republic (CAR). More than 80 percent of the country is controlled by or under the influence of armed militia groups. The security and humanitarian situation has been disastrous for the past 10 months. In recent days, the towns of Bangassou, Gambo and Béma, situated in the east of the country, have been the scene of massacres and sectarian violence. While the leaders of the armed groups shoulder much of the blame, they are not the only ones responsible for this escalation of violence. Political actors and their support networks, operating more discretely in the background but equally hungry for power and personal gain, are supporting and perpetuating these crimes. This political system, based on the manipulation of violence, is fueling trafficking, threatening the stability of the region and leaving the population of an entire country in profound distress. To bring an end to this crisis, there is an urgent need to delegitimize these actors who are perpetrating violence and yet involved in the peace process, to strengthen the implementation of judicial mechanisms and targeted sanctions and to tackle these trafficking networks, in order to pave the way for a peace dialogue. -

Africa's Role in Nation-Building: an Examination of African-Led Peace

AFRICA’S ROLE IN NATION-BUILDING An Examination of African-Led Peace Operations James Dobbins, James Pumzile Machakaire, Andrew Radin, Stephanie Pezard, Jonathan S. Blake, Laura Bosco, Nathan Chandler, Wandile Langa, Charles Nyuykonge, Kitenge Fabrice Tunda C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2978 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0264-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force photo/ Staff Sgt. Ryan Crane; Feisal Omar/REUTERS. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, the African Union (AU) and subregional organizations in Africa have taken on increasing responsibilities for peace operations throughout that continent. -

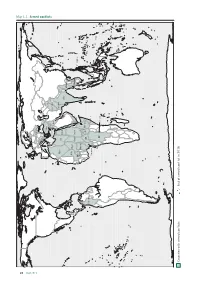

Armed Conflicts

Map 22 1 . 1. Armed conicts Ukraine Turkey Syria Palestine Afghanistan Iraq Israel Algeria Pakistan Libya Egypt India Myanmar Mali Niger Chad Sudan Thailand Yemen Burkina Philippines Faso Nigeria South Ethiopia CAR Sudan Colombia Somalia Cameroon DRC Burundi Countries with armed conflicts End2018 of armed conflict in Alert 2019 1. Armed conflicts • 34 armed conflicts were reported in 2018, 33 of them remained active at end of the year. Most of the conflicts occurred in Africa (16), followed by Asia (nine), the Middle East (six), Europe (two) and America (one). • The violence affecting Cameroon’s English-speaking majority regions since 2016 escalated during the year, becoming a war scenario with serious consequences for the civilian population. • In an atmosphere characterised by systematic ceasefire violations and the imposition of international sanctions, South Sudan reached a new peace agreement, though there was scepticism about its viability. • The increase and spread of violence in the CAR plunged it into the third most serious humanitarian crisis in the world, according to the United Nations. • The situation in Colombia deteriorated as a result of the fragility of the peace process and the finalisation of the ceasefire agreement between the government and the ELN guerrilla group. • High-intensity violence persisted in Afghanistan, but significant progress was made in the exploratory peace process. • The levels of violence in southern Thailand were the lowest since the conflict began in 2004. • There were less deaths linked to the conflict with the PKK in Turkey, but repression continued against Kurdish civilians and the risk of destabilisation grew due to the repercussions of the conflict in Syria. -

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic: Challenges and Priorities High-level dialogue on building support for key SSR priorities in the Central African Republic, 21-22 June 2016 Cover Photo: High-level dialogue on SSR in the CAR at the United Nations headquarters on 21 June 2016. Panellists in the center of the photograph from left to right: Adedeji Ebo, Chief, SSRU/OROLSI/DPKO; Jean Willybiro-Sako, Special Minister-Counsellor to the President of the Central African Republic for DDR/SSR and National Reconciliation; Miroslav Lajčák, Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic; Joseph Yakété, Minister of Defence of Central African Republic; Mr. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA. Photo: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic The report was produced by the Security Sector Reform Unit, Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, United Nations. © United Nations Security Sector Reform Unit, 2016 Map of the Central African Republic 14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° AmAm Timan Timan The boundaries and names shown and the designations é oukal used on this map do not implay official endorsement or CENTRAL AFRICAN A acceptance by the United Nations. t a SUDAN lou REPUBLIC m u B a a l O h a r r S h Birao e a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 10 h r ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh k Garba Sarh Bahr Aou CENTRAL Ouanda AFRICAN Djallé REPUBLIC Doba BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Sam -

Year: 2019 Version 4 – 13/05/2019 HUMANITARIAN

Year: 2019 Ref. Ares(2019)3315226 - 21/05/2019 Version 4 – 13/05/2019 HUMANITARIAN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (HIP) CENTRAL AFRICA1 AMOUNT: EUR 63 850 000 The present Humanitarian Implementation Plan (HIP) was prepared on the basis of the financing decision ECHO/WWD/BUD/2019/01000 (Worldwide Decision) and the related General Guidelines for Operational Priorities on Humanitarian Aid (Operational Priori- ties). The purpose of the HIP and its annex is to serve as a communication tool for DG ECHO2's partners and to assist them in the preparation of their proposals. The provisions of the Worldwide Decision and the General Conditions of the Agreement with the Europe- an Commission shall take precedence over the provisions in this document. This HIP co- vers mainly Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR) and Chad. It may also respond to sudden or slow-onset new emergencies in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé and Principe, if important unmet humanitarian needs emerge, given the exposure to risk and vulnerabilities of populations in these countries. 0. MAJOR CHANGES SINCE PREVIOUS VERSION OF THE HIP Third modification as of 13/05/2019 Central African Republic: The humanitarian crisis remains severe with no signs of improvement in the past months and despite the signature of the peace agreement signed between the Government and 14 armed groups in February 2019. An update of the Humanitarian Needs Overview (published on 27 March 2019) underlined the deterioration of the humanitarian situation with urgent funding requirements. The crisis in the Central African Republic is considered a forgotten crisis which remains largely underfunded. In order to address the needs of the most affected populations by the crisis, in the prioritized areas (based on the needs and as defined in the technical annex), the HIP is increased by an amount of EUR 3 million. -

French Intervention in Africa Reflects Its National Politics

5/11/2017 Africa at LSE – French Intervention in Africa Reflects its National Politics French Intervention in Africa Reflects its National Politics Eva Nelson analyses the underlying motivations in France’s foreign policy towards Africa. The long view of French foreign policy in Africa is paved by conflict of interest. Some politicians are tempted to pull out of the continent for fear of accusation of neocolonialism, somewhat incompatible with President Hollande’s definition of the Francafrique. Others, looking forward to re election, are more preoccupied with appeasing national fears of terrorism by keeping a grip on the Sahel – which they hope will secure them votes from an electorate that begs for heightened national security. This paradox in policy is best witnessed by asymmetric reactions to recent French intervention in Mali and the Central African Republic. Civil wars were taking place at the same time in both countries, but the French media and public opinion reacted differently to each. The government received praise for intervening in Northern Mali, while involvement in the Central African Republic was barely covered, if not overlooked, by the French domestic audience. How to explain such a divide in public opinion for two identical military interventions? Unsurprisingly, it was due to the perceived relationship between the global jihad narrative and domestic security issues, and reinforced by public denial of France’s postcolonial responsibility for conflict in Central Africa. Refugee families from Mali in Mentao refugee camp, northern Burkina Faso Photo Credit: Oxfam International via Flickr (http://bit.ly/2dDJsgj) CC BYNCND 2.0 In early 2012, rebels from the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a Tuareg independence movement, seized strategic cities in Mali’s northern territory before eventually overthrowing the government. -

France's War in Mali: Lessons for an Expeditionary Army

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. C O R P O R A T I O N France’s War in Mali Lessons for an Expeditionary Army Michael Shurkin Prepared for the United States Army Approved for public release; distribution unlimited For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr770 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. -

Security Council Distr.: General 17 April 2014

United Nations S/2014/275 Security Council Distr.: General 17 April 2014 Original: English Letter dated 15 April 2014 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith a note verbale dated 4 April 2014 from the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations, pursuant to Security Council resolution 2127 (2013) (see annex). I should be grateful if you would bring the present letter and its annex to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 14-30384 (E) 210414 210414 *1430384* S/2014/275 Annex [Original: French] The Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations presents its compliments to the Secretary-General of the United Nations and has the honour to refer to Security Council resolution 2127 (2013) concerning the situation in the Central African Republic. Pursuant to paragraph 50 of the resolution, the Permanent Mission of France transmits herewith the second report on the operational activities of the French force Sangaris deployed in the Central African Republic, along with a table of the joint operations undertaken with the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA). The Permanent Mission would be grateful if the Secretary-General would bring these documents to the attention of the Security Council. 2/11 14-30384 S/2014/275 Enclosure Second report on Operation Sangaris Support to the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic in the discharge of its mandate 22 March 2014 1. Basis of the support to the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA) • Security council resolution 2127 (2013) of 5 December 2013 authorizes the French forces in the Central African Republic, within the limits of their capacities and areas of deployment, and for a temporary period, to take all necessary measures to support MISCA in the discharge of its mandate. -

Breaking the Vicious Cycle Between Hunger & Conflict

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 1 CASE STUDY BREAKING THE VICIOUS CYCLE BETWEEN HUNGER & CONFLICT IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC An Action against Hunger case study JUNE 2018 CASE STUDY 2 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC CASE STUDY STATEMENT ON COPYRIGHT COPYRIGHT © Action against Hunger Reproduction is permitted providing the source is credited, unless otherwise specified. If reproduction or use of textual and multimedia data (sound, images, software, etc.) are submitted for prior authorization, such authorization will cancel the general authorization described above and will clearly indicate any restrictions on use. NON-RESPONSABILITY CLAUSE The present document aims to provide public access to information concerning the actions and policies of Action against Hunger. The objective is to disseminate information that is accurate and up-to-date on the day it was initiated. We will make every effort to correct any errors that are brought to our attention. This information: • is solely intended to provide general information and does not focus on the particular situation of any physical person, or person holding any specific moral opinion; • is not necessarily complete, exhaustive, exact or up-to-date; • sometimes refers to external documents or sites over which the Authors have no control and for which they decline all responsibility; • does not constitute legal advice. The present non-responsibility clause is not aimed at limiting Action against Hunger responsibility contrary to the requirements of applicable national legislation, or at denying responsibility in cases where the same legislation makes it impossible. Acknowledgements: we would like to thank all the Action against Hunger teams in the Central African Republic as well as the other actors we met on site who, with great patience and generosity, provided us with contextual information that contributed to our understanding of the issue of hunger and conflict in this country. -

Failing to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 7, September 2015 Too little, too late: Failing to prevent atrocities in the Central African Republic Evan Cinq-Mars The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource for governments, international institutions and civil society on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of Humanity United. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Evan Cinq-Mars is an Advocacy Officer at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, where he monitors populations at risk of mass atrocities in Central African Republic (CAR), Burundi, Guinea and Mali. Evan also coordinates the Global Centre’s media strategy. Evan has undertaken two research missions to CAR since March 2014 to assess efforts to uphold the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). He has appeared as an expert commentator on the CAR situation on Al Jazeera and the BBC, and his analysis has appeared in Bloomberg, Foreign Policy, The Globe and Mail, Radio France International, TIME and VICE News. Evan was previously employed by the Centre for International Governance Innovation. He holds an M.A. in Global Governance, specializing in Conflict and Security, from the Balsillie School of International Affairs at the University of Waterloo. COVER PHOTO: Following a militia attack on a Fulani Muslim village, wounded children are watched over by Central African Republic soldiers in Bangui. -

The Central African Republic Crisis

The Central African Republic crisis March 2016 Nathalia Dukhan About this report This report provides a synthesis of some of the most recent, high-quality literature on the security and political processes in Central African Republic produced up to the end of January 2016. It was prepared for the European Union’s Instrument Contributing to Stability and Peace, © European Union 2016. The views expressed in this report are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of GSDRC, its partner agencies or the European Commission. This is the second review published by GSDRC on the situation in the Central African Republic. The first review of literature was published in June 2013 and provides a country analysis covering the period 2003- 2013. It is available at: http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/car_gsdrc2013.pdf. Expert contributors GSDRC would like to thank the following experts who have contributed to the production of this report: Carolina Reyes Aragon, UN Panel of Experts on the CAR Jocelyn Coulon, Réseau de Recherche sur les Opérations de la Paix Manar Idriss, Independent Researcher Thibaud Lesueur, International Crisis Group Thierry Vircoulon, International Crisis Group Ruben de Koning, UN Panel of Experts on the CAR Yannick Weyns, Researcher at IPIS Research Source for map of CAR on following page: International Peace Information Service (PIS) www.ipisresearch.be. Suggested citation Dukhan, N. (2016). The Central African Republic crisis. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham. About GSDRC GSDRC is a partnership of research institutes, think-tanks and consultancy organisations with expertise in governance, social development, humanitarian and conflict issues. -

Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in the Central African Republic

United Nations S/2014/857 Security Council Distr.: General 28 November 2014 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in the Central African Republic I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2149 (2014), by which the Council established the United Nations Multidime nsional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) and requested me to report to the Council every four months starting on 1 August 2014. The report provides an update on the situation in the Central African Republic since my report of 1 August (S/2014/562). It also provides an update on the transfer of authority from the African-led International Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA) to MINUSCA on 15 September and on the implementation of the MINUSCA mandate. II. Major developments A. Security, human rights and humanitarian developments 2. The security situation in the Central African Republic remains highly volatile. Frequent clashes among armed groups or criminal elements and attacks against civilians continue. Fragmentation, internal leadership struggles and the lack of command-and-control authority within the anti-balaka and among ex-Séléka factions were accompanied by continued clashes between and among those armed groups in Bangui and other parts of the country. The human rights situation remains serious, with numerous cases of human rights violations and abuses, including killings, lootings, the destruction of property, violations of physical integrity and restrictions on freedom of movement. Throughout the country, widespread insecurity, threats of violence and gross human rights violations committed by armed elements continue to adversely affect the dire humanitarian situation facing the civilian population.