Mentoring Methodological Framework for MINT Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

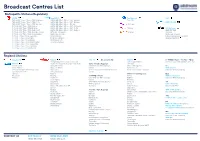

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Annual Report to Shareholders

create distribute engage ifc The Year in Brief 2 Chairman’s Address 4 Chief Executive Officer’s Address 6 Divisional Results 8 Operational Review 16 Nine Cares create 17 Governance 18 Board of Directors 20 Directors’ Report distribute 25 Remuneration Report 44 Operating and Financial Review 48 Financial Report engage 108 Shareholder Information ibc Corporate Directory During FY17, Nine achieved its goal of turning the Network performance around, after a disappointing year in FY16. Momentum in Free To Air TV turned positive for Nine in Q2, and this improvement continued throughout the remainder of the financial year. The success of Nine’s broadcast content has, in turn, driven take-up and use of 9Now which has grown exponentially to over 4 million registered users, and is becoming a valuable contributor to the P&L. Nine’s Subscription Video on Demand platform Stan, has matured significantly over the past 12 months and now holds a clear number 2 position in the market. Nine’s digital publishing business has been successfully repositioned post the Microsoft relationship, laying the foundations for growth into the future. All of Nine’s businesses are built around the key content verticals of news, sport, lifestyle and entertainment. Result In Brief In FY17, on a revenue decline of 4%, Nine reported Group EBITDA of $206 million, up 2% on FY16. Driving this growth was an underlying cost decrease of 1%, and a reported cost decrease of 4% which included the Government regulated licence fee relief of $33 million. Net Profit after Tax increased by 3% to $123.6 million compared to the Pro Forma FY16 result. -

Business Wire Catalog

Asia-Pacific Media Pan regional print and television media coverage in Asia. Includes full-text translations into simplified-PRC Chinese, traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean based on your English language news release. Additional translation services are available. Asia-Pacific Media Balonne Beacon Byron Shire News Clifton Courier Afghanistan Barossa & Light Herald Caboolture Herald Coast Community News News Services Barraba Gazette Caboolture News Coastal Leader Associated Press/Kabul Barrier Daily Truth Cairns Post Coastal Views American Samoa Baw Baw Shire & West Cairns Sun CoastCity Weekly Newspapers Gippsland Trader Caloundra Weekly Cockburn City Herald Samoa News Bay News of the Area Camden Haven Courier Cockburn Gazette Armenia Bay Post/Moruya Examiner Camden-Narellan Advertiser Coffs Coast Advocate Television Bayside Leader Campaspe News Collie Mail Shant TV Beaudesert Times Camperdown Chronicle Coly Point Observer Australia Bega District News Canberra City News Comment News Newspapers Bellarine Times Canning Times Condobolin Argus Albany Advertiser Benalla Ensign Canowindra News Coober Pedy Regional Times Albany Extra Bendigo Advertiser Canowindra Phoenix Cooktown Local News Albert & Logan News Bendigo Weekly Cape York News Cool Rambler Albury Wodonga News Weekly Berwick News Capricorn Coast Mirror Cooloola Advertiser Allora Advertiser Bharat Times Cassowary Coast Independent Coolum & North Shore News Ararat Advertiser Birdee News Coonamble Times Armadale Examiner Blacktown Advocate Casterton News Cooroy Rag Auburn Review -

Adstream Powerpoint Presentation

Broadcast Centres List Metropolitan Stations/Regulatory Nine (NPC) 7 BCM 7 BCM cont’d Nine (NPC) cont’d Ten Network 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton QTQ Nine Brisbane Ten HD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba STW Nine Perth Ten SD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville TCN Nine Sydney One (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Channel 11 (all metro) 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth SBS National 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD / SBS Free TV CAD 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast ABC GTV Nine Melbourne Viceland 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay Regional Stations Prime 7 cont’d SCA TV Cont’d WIN TV cont’d VIC Mildura Bendigo WIN / 11 / One Regional: WIN Ballarat Send via WIN Wollongong Imparja TV Newcastle Bundaberg Albury Orange/Dubbo Ballarat Canberra NBN TV Port Macquarie/Taree Bendigo QLD Shepparton Cairns Central Coast Canberra WIN Rockhampton South Coast Dubbo Cairns Send via WIN Wollongong Coffs Harbour -

Authorized Abbreviations, Brevity Codes, and Acronyms

Army Regulation 310–50 Military Publications Authorized Abbreviations, Brevity Codes, and Acronyms Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 15 November 1985 Unclassified USAPA EPS - * FORMAL * TF 2.45 05-21-98 07:23:12 PN 1 FILE: r130.fil SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 310–50 Authorized Abbreviations, Brevity Codes, and Acronyms This revision-- o Contains new and revised abbreviations, brevity codes , and acronyms. o Incorporates chapter 4, sections I and II of the previous regulation into chapters 2 and 3. o Redesignates chapter 5 of the previous regulation as chapter 4. USAPA EPS - * FORMAL * TF 2.45 05-21-98 07:23:13 PN 2 FILE: r130.fil Headquarters Army Regulation 310–50 Department of the Army Washington, DC 15 November 1985 Effective 15 November 1985 Military Publications Authorized Abbreviations, Brevity Codes, and Acronyms has been made to highlight changes from the a p p r o v a l f r o m H Q D A ( D A A G – A M S – P ) , earlier regulation dated 15February 1984. ALEX, VA 22331–0301. Summary. This regulation governs Depart- m e n t o f t h e A r m y a b b r e v i a t i o n s , b r e v i t y Interim changes. Interim changes to this codes, and acronyms. regulation are not official unless they are au- thenticated by The Adjutant General. Users Applicability. This regulation applies to el- will destroy interim changes on their expira- ements of the Active Army, Army National Guard, and U.S. -

Federal Government Product Highlights

FEDERAL2019 GOVERNMENT PRODUCT HIGHLIGHTS FCA US 2019 MODEL YEAR GSA LINEUP DODGE CHARGER DODGE CHARGER PURSUIT DODGE DURANGO PURSUIT DODGE DURANGO DODGE DURANGO SPECIAL SERVICE ITEM 10B (Page 3) ITEM 17 (Page 15) ITEM 100L (Page 23) ITEM 91B & 96B (Page 25) ITEM 100C (Page 34) DODGE GRAND CARAVAN CHRYSLER PACIFICA HYBRID DODGE JOURNEY JEEP® WRANGLER JEEP COMPASS JEEP CHEROKEE ITEM 20 (Page 36) ITEM 20P (Page 43) ITEM 91 & 96 (Page 50) ITEM 5A, 112 (Page 56) ITEM 98A & 99A (Page 63) ITEM 98, 99 & 99B (Page 74) RAM 2500 & 3500 JEEP GRAND CHEROKEE RAM 1500 CLASSIC ITEM 44, 49, 52, 57, 56R, 44A, 44B, 49A, 49B, RAM 1500 SPECIAL SERVICE RAM PROMASTER® ITEM 100A & 105A (Page 81) ITEM 41, 46, 41C, 46C, 50 & 55 (Page 89) 52A, 54, 57A & 59A (Page 97) ITEM 55C (Page 111) ITEM 31, 32 & 34 (Page 113) GSA ITEM 10B UP TO 2019 AWD 300 8-SPEED DODGE CHARGER AVAILABLE HORSEPOWER AUTOMATIC TRANS SELECT STANDARD FEATURES Acoustic Windshield and Front-door Glass Active Head Restraints(1) Air Filtering Automatic Headlamps Battery — 730-amp, maintenance-free Capless Fuel Filler System with Interior Fuel Door Release Cargo Compartment Dress-up with Cargo Net Center Console with 12-volt Power Outlet Child Seat Upper Tether Anchors Driver and Front-passenger Advanced Multistage Air Bags(2) Dual Exhaust System Electronic Power Steering Electronic Speed Control Electronic Stability Control(3) Front and Rear Floor Mats Front and Rear Solar-Control Glass Full-length Floor Console SAFETY & SECURITY Active Head Restraints(1) — Standard Advanced Multistage Driver and -

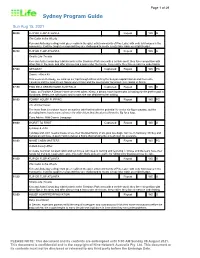

9Life Aug 15

Page 1 of 29 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 15, 2021 06:00 FLIP OR FLOP ATLANTA Repeat WS G The Cabin in the Woods Ken and Anita buy a dingy mint green cabin in the quiet artist community of Pine Lake; with only 350 houses in the community, it will be tough to comp and they are challenged to create a cozy lake cabin on a tight budget. 06:30 FLIP OR FLOP ATLANTA Repeat WS G Smells Like Trouble Ken and Anita Corsini buy a brick ranch in the Gresham Park area with a terrible smell; they face competition with other flips in the area, and after discovering a leak under the house, they realize they face a massive undertaking. 07:00 GETAWAY Captioned Repeat WS PG Scenic - Africa #3 This week on Getaway, we wind up our trip through Africa visiting the Kenyan capital Nairobi and then onto Tanzania and the magnificent Ngorongoro Crater and the spectacular Serengeti, lion capital of Africa. 07:30 FIND ME A DREAM HOME AUSTRALIA Captioned Repeat WS G Today, on Find Me A Dream Home we meet writer, Kirsty, a dream home hunter who is looking for the perfect pad in Bundoora, Melbourne with a pool and a room she can dedicate to her writing. 08:00 ZOMBIE HOUSE FLIPPING Repeat WS PG The Animal House The team finds a rundown house on a prime lakefront lot with the potential for a nice six-figure payday, but the decaying home has become a haven for wild critters that threaten to throw the flip for a loop. -

National Transit Database (Ntd) Report Directly Operated (Id# 9154) for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2009

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority California national transit database (ntd) report directly operated (id# 9154) for the fiscal year ended june 30, 2009 submitted: october 30, 2009 Model Update Update Issues Module Form Name Service User ~ £ Basic Information Identification (B-10) EDT9154 10/26/09 0 0 Contacts (B-20) NTD9154 9/16/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) TRANSPORTATION CONCEPTS, INC. -MB EDT9154 10/27/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation - MB EDT9154 10/22109 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) SOUTHLAND TRANSIT INC. - MB EDT9154 9/18/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) VEOLIA TRANSPORTATION SERVICES INC- MB EDT9154 9/15/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) FIRST TRANSIT, INC. - MB EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) VPSIINC. - VP EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Contractual Relationship (B-30) ENTERPRISE RfDESHARE - VP EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Financial Sources of Funds-Funds Expended & Funds Earned (F-10) NTD9154 11/23/09 0 0 Uses of Capital (F-20) EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Operating Expenses (F-30) HRDO EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Operating Expenses (F-30) LRDO EDT9154 10/28/09 0 0 Operating Expenses (F-30) MBDO EDT9154 10/28/09 0 0 0 Operating Expenses (F-30) MBPT EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Operating Expenses (F-30) VPPT EDT9154 9/16/09 0 0 0 Operating Expenses Summary (F-40) NTD9154 11/23/09 Assets 9/14/09 0 0 Stations and Maintenance Facilities - DO (A-1O) HRDO EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Stations and Maintenance Facilities - DO (A-10) LRDO EDT9154 9/14/09 0 0 Stations -

Copyright and Designs – Contents

LAWS3480 – IP: Copyright and Designs IP: Copyright and Designs – Contents 1. Introduction to IP ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The nature of intellectual property ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The constitutional basis for IP law ....................................................................................................... 1 1.3 International influences ........................................................................................................................ 1 Key principles ............................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Introduction to Copyright: History and Basic Principles ........................................................ 4 2.2 History of Copyright Law ...................................................................................................................... 4 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 8 .................................................................................................................. 4 Royal Prerogatives and the Stationers’ Company ..................................................................................... 4 The Statute of Anne 1710 .......................................................................................................................... 4 The ‘literary property wars’ ........................................................................................................................ -

M .. T-4. T N Bl{ Ttn'

M .. t-4.t N Bl{ttN' - -!i�Jt<�i.L-'- ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1978-79 '/ Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1978-79 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1979 © Commonwealth of Australia 1979 Printed by The Courier-Mail Printing Service, Campbell Street, Bowen Hills, Q. 4006. The Honourable the Minister for Post and Telecommunications In conformity with the provisions of section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, I have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal forthe period 1 July 1978 to 30 June 1979. Bruce Gyngell Chairman 17 September 1979 Ill CONTENTS PART/ INTRODUCTION Page Legislation 1 Membership of the Tribunal 1 Functions of the Tribunal 2 Meetings of the Tribunal 2 Staff of the Tribunal 2 Overseas Visits 3 Addresses given by Tribunal Members and Staff 3 Location of Tribunal's Offices 4 Financial Accounts of the Tribunal 5 PART II. GENERAL Broadcasting and Television Services in operation since 1949 6 Financial Results - Commercial Broadcasting and Television Stations 7 Fees for Licences for Commercial Broadcasting and Television 9 Stations Broadcasting and Televising of Political Matter 12 Complaints from Viewers and Listeners about Programs 15 Children's Program Committee 18 Implementation of the Recommendations of the Self-Regulation 19 Report Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs - 20 Freedom of Information PART III PUBLIC INQUIRIES Introduction 21 Legislation 21 Procedures forInquiries 21 Outline of -

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Productivity Commission Inquiry Into Broadcasting

PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO BROADCASTING SUBMISSION FROM THE FEDERATION OF AUSTRALIAN COMMERCIAL TELEVISION STATIONS MAY 1999 SUMMARY OF SUBMISSION Governments everywhere in the world have intervened in the broadcasting industry to secure a range of economic, social and cultural objectives. Australian Governments have done so for many reasons. Some of these reasons are now of diminishing relevance, while others remain highly relevant on social, cultural or economic grounds. This submission assesses key broadcasting policies, in order to ascertain whether the public benefits outweigh the costs to the community of the restrictions imposed on the industry, or on competition within the industry. Currently, Australia has one of the best and most comprehensive free-to-air broadcasting systems in the world. It offers diversity of programming, quality, national coverage and local services, and programs reflecting our identity as Australians. This has been achieved through a structure of broadcasting developed over many decades. It involves a hybrid system of advertiser-funded and government-funded broadcasters. The advertiser-funded commercial free-to-air services are the predominant element in the system. These locally-licensed services are highly competitive and efficient. They provide much more local service and locally-produced programming - the costliest service components - than would be expected in a country with such a small population. They are able to do this because of long-standing (though recently reviewed) regulatory limits on the number of commercial services in each licence area. These impressive (and costly) service levels are already proving hard to maintain in the face of limited advertising growth and expanding competition from other media.