South African Memories Uidander Risings Or Resistances, and Long Before the Jameson Raid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2014

Volume 41 Number 1 December 2014 for the engravings, only the oldest inhabitant had one: ‘They are animals that have been turned to stone; how else could brand marks be on stone?’ Although the Turkana do brand their live- stock, they do it for a number of complex ritual reasons rather than to indicate ownership as the ancient Cushites are reported to have done. The Turkana only brand male animals and not every animal is branded. Often only the best or favourite Reports covering the period January to July 2014 animals are branded and the practice is thus used as an opportunity to show off. Similarities between the stone engravings and livestock branding is probably the result of mimicry as many markings on Turkana livestock are not similar to those of the stone engravings. Often EVENING LECTURES Intricate livestock branding they mark their animals by cutting notches in their animals’ ears, but the same individual will use different symbols on different species of animal. The Turkana believe the skin of an animal acts as the interface between this world and the next, and the act of cutting or branding the skin of Through the skin: the meaning of rock and skin markings at animals thus enables humans to access the spirit world. Livestock with the same clan marks are Namaratung’a in Northern Kenya (6 February 2014) guarded by the spirits of the same ancestors. This joins livestock, humans and ancestors together. Thembi Russell, School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Since stone cannot be used to communicate with the ancestors, brand marks lose their purpose Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand when placed on any surface other than skin. -

Rnr. WAR in SOUTH AFRICA

11(5 rnr. WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA JAMKS, Major H. E. R. : Army Medical Service Jomt, Mr. : sentenced for carrying on illicit reform work, vf 542 liquor traffic, '00, i 122 JAMES, Lieut. (R.N.): at Colenao, ii 442; at JOHANNESBURG : Spion Kop, lit 283, 286 Administration during early months of JAMES, Lieut. : at Lichtenburg, v 223 war, iv 149-52; after British occupation, vi JAMESON, Dr. A. : appointed Commissioner of 683-01, iv 497 Land* in Transvaal, vi 57 Begbie's factory manufactures ammuni- : Director General iii 82 ii iv 150 JAMESON, Surg.-Gen. Army tion, ; wrecked, 70, Medical Service, vi 02, 643 Boers approve Kruger's franchise pro- : 1 i JAMKSON, Dr. L. S. portrait, 150 ; Adminis- posals, 288 i trator of Rhodesia ; prevents Boer invasion, Bogus conspiracy May 16 '99, 301, 302 1891, 106 ; undertakes to smuggle rifles into Chamber of Mines President endeavours ] 53 i 141 Johannesburg, ; force on Transvaal to allay excitement. '94, ; protests a ,-i i MSI, i 121 border, 160 ; Reformers request his aid, liquor traffic, ; attitude on raid into Transvaal 235 163, -164 ; makes ; cap- dynamite monopoly, in of tured at Doornkop, 167 ; leader of Cape Chamber of Trade favour Chinese, Progressives, vi 192 ; forms ministry, 193 ; vil!9 appreciation of administration, 193; ad- Chamberlain, Mr. arrives, vi 80 ministrative difficulties, 194 ; efforts to enlist Civil administration municipal govern- support of Moderates, 194 ; review of ministry ment conferred by Kruger, 218 ; condemiifd 195 227 vl (1904-8), 193-5 ; resignation and defeat, ; by Uitlanders, ; organization, v 270, supports movement for South African Union, 15, 16 iii 210 ; services at Convention, 214 ; suggests Clothing factory started by Boers, 82 title for Orange River Colony, 217 Commando see under REOIMENTA i. -

Military History Journal Ambush at Kalkheuwel Pass, 3 June 1900 By

The South African Military History Society Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging Military History Journal Vol 9 No 4 - December 1993 (incorporating Museum Review) Ambush at Kalkheuwel Pass, 3 June 1900 by Prof I B Copley, Dept of Neurosurgery, Medunsa Introduction After Lord Roberts' entry into Johannesburg, he established his headquarters at Orange Grove and, for two days, the army rested. General French's Cavalry, with General Hutton's Mounted Infantry, was bivouacked at Bergvlei near the dynamite factory. The rest of the army was positioned two to six miles north of the town.(1) Mounted Infantry entering Johannesburg (SA National Museum of Military History) Officers of regiments of the Cavalry such as the Carabiniers (6th Royal Dragoon Guards) were able to visit Johannesburg when it was only fifteen years old and admire the 'fine buildings, broad, clean streets, luxurious hotels and well appointed clubs' and the surrounding suburban villas in contrast to the 'one-horse townships' they had experienced thus far. They also commented on the high prices.(2) In view of his over-extended lines of communication, Lord Roberts was faced with the question of whether he should move on to Pretoria. The railway line, stretching 1 000 miles to Cape Town, was in constant threat of Boer guerilla attacks, particularly across the Orange Free State where General Christiaan de Wet was lurking with some three thousand men and ten guns at his disposal. Attacks had already occurred at Roodepoort near Heilbron, Lindley and Biddulphsberg and there -

Addendum HMP Klapperkop Final August 2014

AFRICAN HERITAGE CONSULTANTS CC 2001/077745/23 DR UDO S KÜSEL Tel/Fax: (012) 567 6046 P.O. Box 652 Cell: 082 498 0673 Magalieskruin E-mail: [email protected] 0150 Addendum to Cultural Heritage Management Plan: for the Klapperkop Nature Reserve, City of Tshwane, the Environmental Management Department City of Tshwane, Report: AE01302V Compiled By Dr A.C. Van Vollenhoven January 2013 August 2014 African Heritage Consultants CC _HMP Addendum Klapperkop August 2014 Prepared by ……………………………………………. …………………………………… Udo S Küsel Siegwalt U Küsel Accredited Professional Archaeologist for the SADC Pr(LArch) SACLAP Reg. 20182 Region (Field Director Stone Age, Filed Supervisor BL Landscape Architecture Iron Age and Colonial Period Industrial Archaeology): BA (Hons) Archaeology (Cum laude) Professional Member 068 Accredited professional archaeologist for D Phil Cultural History, the SADC Region Member No. 367 MA Archaeology Post-graduate Diploma in Museum and Heritage Studies Note that this Management Plan is based on the 2008 SAHRA guidelines for the compilation of Site Management Plans: Guidelines for the development of plans for the management of heritage sites or places August 2014 2 African Heritage Consultants CC _HMP Addendum Klapperkop August 2014 Executive Summary The purpose of this Heritage Management Plan for Fort Klapperkop is to address the impact of relocating the South African War Memorial to the South African Defence Force Memorial Complex at the Voortrekker Monument and to make recommendations on: • The relocation process • The rehabilitation of the site once the removal has taken place • The future redevelopment of the fort and surrounding infrastructure August 2014 3 African Heritage Consultants CC _HMP Addendum Klapperkop August 2014 Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... -

Searching Queen's Cowboys

Searching for the Queen’s Cowboys Travels in South Africa Filming a documentary on Strathcona’s Horse and the Anglo-Boer War Tony Maxwell Copyright © 2010 Tony Maxwell All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Maxwell, Tony, 1943- Searching for the Queen’s cowboys : travels in South Africa filming a documentary on Strathcona’s Horse and the Anglo-Boer War / Tony Maxwell. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9683256-1-2 1. Maxwell, Tony, 1943- --Travel--South Africa. 2. South Africa-- Description and travel. 3. South African War, 1899-1902. 4. South Africa-- History, Military. I. Title. DT1738.M38 2009 916.80466 C2009-905986-X Book design: BookDesign.ca Printed in USA Published in 2009 by BRATONMAX P O Box 146, Red Deer, Alberta Canada T4N 5E7 www.bratonmax.com 2 SEARCHING FOR THE QUEEN’S COWBOYS Contents 1 Lord Strathcona’s Cowboys . 15 2 London . 37 3 Africa . 49 4 Pretoria . 68 5 Mpumalanga . 94 6 Lydenburg . 114 7 Politics and Wars . 140 8 Kruger’s Legacy . 159 9 Wolvespruit . 188 10 Isandlwana . 212 11 Rorke’s Drift . 240 12 Spion Kop . 252 13 The Hunt For De Wet . 272 14 Magersfontein . 291 15 The City of Gold . 315 Searching for the Queen’s Cowboys 3 For my parents Thelma and Frank Maxwell 4 SEARCHING FOR THE QUEEN’S COWBOYS Acknowledgements Travel has always been a very important part of my life. -

Environmental Management Services Department

Environmental Management Services Department A CULTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE VOORTREKKER MONUMENT NATURE RESERVE, CITY OF TSHWANE REPORT: AE01465V By: Dr. A.C. van Vollenhoven (L.Akad. SA) Accredited member of ASAPA Accredited member of SASCH NOVEMBER 2014 AC van Vollenhoven BA, BA (Hons), DTO, NDM, MA (Archaeology) [UP], MA (Culture History) [US], DPhil (Archaeology) [UP], Management Diploma [TUT], DPhil (History) [US] 1 3 SUMMARY This document entails a cultural heritage resources management plan for the Voortrekker Monument Nature Reserve. Eight sites of cultural heritage importance were identified. This excludes the Voortrekker Monument, which is a declared Grade I heritage site and which is dealt with in other SAHRA documents. These are discussed and heritage management guidelines are given. Some basic principles for heritage management which are applicable will also be discussed. These are the basic conservation and preservation principles to be used in managing cultural resources. Recommendations made in the document are done within the parameters of the National Heritage Resources Act (25 of 1999). The management plan is an open document meaning that it should be adapted and reassessed from time to time. A continuation period of at least five years is given. However any developments done before the expiry of the five year period should be used to re-evaluate the impact on cultural resources and to make the necessary adaptations to the document. The five year period ends in 2019. 2 DISCLAIMER: Although all possible care is taken to identify all sites of cultural importance during the survey of study areas, the nature of archaeological and historical sites are as such that it always is possible that hidden or subterranean sites could be overlooked during the study. -

The Potential of Wonderboom Nature Reserve As an Archaeotourism Destination

THE POTENTIAL OF WONDERBOOM NATURE RESERVE AS AN ARCHAEOTOURISM DESTINATION by Victoria-Ann Verkerk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Hereditatis Culturaeque Scientiae (Heritage and Cultural Tourism) in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY HUMANITIES Supervisor: Prof. C. C. Boonzaaier Co-supervisor: Dr N. Ndlovu March 2017 © University of Pretoria UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES RESEARCH PROPOSAL & ETHICS COMMITTEE DECLARATION Full name: Victoria-Ann Verkerk Student Number: 10592483 Degree/Qualification: Magister Hereditatis Culturaeque Scientiae (Heritage and Cultural Tourism) Title of dissertation: The potential of Wonderboom Nature Reserve as an archaeotourism destination I declare that this dissertation is my own original work. Where secondary material is used, this has been carefully acknowledged and referenced in accordance with university requirements. I understand what plagiarism is and am aware of university policy and implications in this regard. ____________________ ____________ Victoria-Ann Verkerk Date ResPEthics Documentation NE 46/04 05/2004 i © University of Pretoria ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation without the help of the following, whom I would like to thank: • God the Father, Jesus and the Holy Spirit, and the Angels for giving me the Bible verse in 2 Chronicles 15:7: ‘But as for you, be strong and do not give up, for your work will be rewarded.’ This verse came to me at the most crucial time of this study. Without this verse, I would not have had the strength to finish this dissertation. • My supervisor, Professor C.C. -

Cross Border Themed Tourism Routes

CROSS-BORDER THEMED TOURISM ROUTES IN THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN REGION: PRACTICE AND POTENTIAL DEPARTMENT OF HERITAGE AND HISTORICAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2019 Table of Contents Page no. List of Abbreviations iii List of Definitions iv List of Tables vii List of Maps viii List of Figures ix SECTION 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT OF THE STUDY 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Background and Context 4 1.3 Problem Statement 6 1.4 Rational of the Study 7 1.5 Purpose of the Study 8 1.6 Research questions 8 1.7 Objectives of the Study 9 SECTION 2: RESEARC H METHOOLODY 10 2.1 Literature Survey 10 2.2 Data Collection 10 2.3 Data Analysis 11 2.4 Ethical Aspects 12 SECTION 3: THEORY ANF LITERATURE REVIEW 13 3.1 Theoretical Framework 13 3.2 Literature Review 15 SECTION 4: STAKEHOLDERS AND CROSS-BORDER TOURISM. 33 4.1 Introduction 33 4.2 Stakeholder Categories and Stakeholders 33 4.3 SADC Stakeholders 34 4.4 Government Bodies 35 4.5 The Tourism Industry 42 4.6 Tourists 53 4.7 Supplementary Group 56 SECTION 5: DIFFICULTIES OR CHALLENGES INVOLVED IN CBT 58 5.1 Introduction 58 i 5.2 Varied Levels of Development 59 5.3 Infrastructure 60 5.4 Lack of Coordination/Collaboration 64 5.5 Legislative/Regulatory Restrictions and Alignment 65 5.6 Language 70 5.7 Varied Currencies 72 5.8 Competitiveness 72 5.9 Safety and Security 76 SECTION 6 – SHORT TERM MITIGATIONS AND LONG TERM SOLUTIONS 77 6.1 Introduction 77 6.2 Collaboration and Partnership 77 6.3 Diplomacy/Supranational Agreements 85 6.4 Single Regional and Regionally Accepted Currency 87 6.5 Investment -

Book Chapter 01

01Introduction “In Words, as Fashions, the same Rule will Hold; Alike Fantastick, if too New, or Old; Be not the first by whom the New are try’d, Nor yet the last to lay the Old aside.” Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism genius loci r u i n s l a y e r s fig. 1.1. Layered montage illustrating design intention and concept. (2010) The layered concept is of a physical and historical origin. It was inspired by the Ukranian artist Mark Khaisman, who uses packaging tape on plexi-glas in various layers to create his artistic impressions 01 - 02 Introduction The intended project in the Lotus Gardens area, Pretoria West is to introduce to the public and create an awareness of the Military Fortification’s in Pretoria. These iconic structures were built during the First and Second Anglo Boer Wars. The project will consist of a visitors centre and an archaeological didactic and research centre. The idea of the visitor is to be made aware and informed of various iconic structures within Pretoria, including Fort Klapperkop, Fort Schanskop, Fort Wonderboompoort, also buildings including the Union Buildings, Voortrekker Monument, Church Square and Freedom Park. The archaeological centre’s focus will be on work done at archaeological sites and mainly the various other Fortifications within Pretoria. Therefore a primary focus being on the tourism potential being created by the project for the area. The Fortification of Pretoria on the various ridges: Magaliesberg, Waterkloof and Waterberg, aimed at the visual safekeeping of Pretoria. The Forts ensured that people could not enter the city willingly during the Anglo Boer Wars. -

1 Dae Vol Spanning in 1895-1896: Die Jameson-Inval

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 3 Nr 5, 1973. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za 1 DAE VOL SPANNING IN 1895-1896: DIE JAMESON-INVAL. PRETORIA BEDREIG INLEIDING Die "Staat van buit Jameson..mval aan de Artillerie afgeleverd", gedateer 2 Januarie 1896: is een van die dokumente van militer-historiese waarde in die Transvaalse Argiefbewaarplek, Pretoria, wat aan die Jameson-inval herinner. Op 2 Januarie 1896 het dr. (later sir) Leander Starr Jameson en sy huur1inge, nadat hulle op Nuwejaarsdag 1896 by Doornkop, naby Krugersdorp, met 500 burgers slaags geraak het, op die plaas Vlakfontein oorgegee. Op hierdie wyse het 'n militere inval ten einde geloop wat, in 'n geskiedkundrige lig beskou, 'n uitvloeisel was van die timperialistiese uitbreidingsbeleid van die westerse nasies gedurende die laaste kwart van die negentiende eeu wat in verband staan met die politieke sienswyses van hulle wat teen die einde van die eeu mag in Suid-AfIIika uitgeoefen het: a. DIE MILITt!:RE ASPEK VAN DIE JAMESON-IN VAL Wat die militere aspek van die Jameson-inval betref, kon genI. P. I. Joubert, kommandant-generaal van die Suid.Afnikaansche RepubIiek, na die gebeure by Doornkop met dankbaarheid getuig dat die TransvaaIse offisiere en manskappe hulle ooreenkomstig die begeerte en verwagting gedra het. Hieraan het die kom- mandant-generaal toegevoeg "dat de hulp van onzenGod en Zijne voorzienigheid den uitslag ten goede der Republiek hebben doen keeren ••.• Behalwe die krygsgevangenes, waarvan die manskappe op 11 Januarie 1896 en dr. Jameson en sy offisiere op 21 Januarie 1896 per trein na Durban vertrek het, het onder meer die volgende blit in die Pretoriase Staatsartilleriekamp' aangekom: 305 perde, sewe-en-tagtig muile, 274 saals, 290 tome, twee-en-sestig saalklede. -

© University of Pretoria

© University of Pretoria 2.1// THE FORTIFICATION OF THE CAPITAL CITY As Pretoria was the capital city of the The Jameson Raid (1895-1896) large- former ZAR Government (1852-1902), ly contributed to the second fortifica- its fortification was a critical project in tion period, when the Boer Republic a final attempt to retain control over was forced to reconsider its defence the former Transvaal. One of the ma- strategies. Taking advantage of the jor drivers in the annexation of the elevated vantage points on the ridges, province was the discovery of gold in four independent forts had been con- 1886(Van Vollenhoven 1998:2). structed by 1898 on the surrounding peripheries (see Figure 4). These are Pretoria was established in 1855 and Fort Wonderboompoort (northern por- its central location was valued by both tal), Fort Schanskop, Fort Klapperkop the British and the Boers, resulting in a (southern portal) and what was then ceaseless battle for supremacy. Due to known as Fort Daspoortrand (western its natural topography, the surround- portal), later renamed by the British as ing ridges were utilized as elevated Fort West. vantage points and strategic locations to protect the entry portals and railway As a result of a disagreement be- routes into the city (Van Vollenhoven tween the ruling authorities of the 1998:2-24). It is also important to note time, the design and construction of the contextual value of the surround- Fort Daspoortrandwas assigned to a ing ridges that connect a series of his- French firm called Schneider and Co., torical artefacts across South Africa. -

Autumn 07 Cover

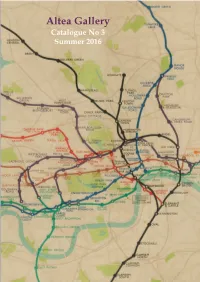

Altea Gallery Covers.qxp_Layout 1 16/05/2016 16:29 Page 1 ALTEA GALLERY Altea Gallery Catalogue No 3 Summer 2016 CATALOGUE No 3 SUMMER 2016 Altea Gallery Covers.qxp_Layout 1 16/05/2016 16:29 Page 2 RECOMMENDED REFERENCE BOOKS MANASEK, F.J. Collecting Old Maps. Revised and Expanded Edition by Marti Griggs & Curt Griggs. Clarkdale, AZ: Old Maps Press, 2015. Hardback, cloth & illus. dustrwapper; pp. 352, illustrated throughout. New. £50 We are European distributor of this thorough guide to collecting antique maps, which includes chapters on what is available to the collector, deciphering dealers’ descriptions, assessing the quality of a map and caring for a collection. First published in 1998, this second edition has been expanded, with many more illustrations. PICKLES, Rosie et al. Map. Exploring the World. London: Phaidon, 2015. Large 4to, cloth & illus. d/w; pp. 352, profusely illustrated. New. £40 Describing maps including a Babylonian world map of c.700 BC, the Hereford Mappa Mundi of c.1300 to maps of the brain, 2014. Front cover: item 10 Back cover: item 7 Altea Gallery Limited Terms and Conditions: 35 Saint George Street SUMIRA, Sylvia. London W1S 2FN Each item is in good condition unless otherwise noted in the description, allowing for the usual minor imperfections. Tel: + 44 (0)20 7491 0010 The Art and History of Globes. Measurements are expressed in millimeters and are taken [email protected] to the plate-mark unless stated, height by width. London: British Library, 2014. 4to, cloth & illus. d/w. pp. 224, www.alteagallery.com (100 mm = approx. 4 inches) illustrated throughout.