December 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Taxonomic Revision of Commicarpus (Nyctaginaceae) in Southern Africa

South African Journal of Botany 84 (2013) 44–64 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb A taxonomic revision of Commicarpus (Nyctaginaceae) in southern Africa M. Struwig ⁎, S.J. Siebert A.P. Goossens Herbarium, Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa article info abstract Article history: A taxonomic revision of the genus Commicarpus in southern African is presented and includes a key to the Received 19 July 2012 species, complete nomenclature and a description of all infrageneric taxa. The geographical distribution, Received in revised form 30 August 2012 notes on the ecology and traditional uses of the species are given. Eight species of Commicarpus with five in- Accepted 4 September 2012 fraspecific taxa are recognized in southern Africa and a new variety, C. squarrosus (Heimerl) Standl. var. Available online 8 November 2012 fruticosus (Pohn.) Struwig is proposed. Commicarpus species can be distinguished from one another by vari- fl Edited by JS Boatwright ation in the shape and indumentum of the lower coriaceous part of the ower and the anthocarp. Soil anal- yses confirmed the members of the genus to be calciophiles, with some species showing a specific preference Keywords: for soils rich in heavy metals. Anthocarp © 2012 SAAB. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Commicarpus Heavy metals Morphology Nyctaginaceae Soil chemistry Southern Africa Taxonomy 1. Introduction as a separate genus (Standley, 1931). Heimerl (1934), however, recog- nized Commicarpus as a separate genus. Fosberg (1978) reduced Commicarpus Standl., a genus of about 30–35 species, is distributed Commicarpus to a subgenus of Boerhavia, but this was not validly throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, especially published (Harriman, 1999). -

Elemental Compositions of Nile Crocodile Tissues (Crocodylus Niloticus) from the Kruger National Park

Elemental compositions of Nile crocodile tissues (Crocodylus niloticus) from the Kruger National Park D van der Westhuizen orcid.org 0000-0001-6482-9262 Dissertation accepted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Science in Zoology at the North-West University Supervisor: Prof H Bouwman Graduation October 2019 24128910 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my Lord and Saviour for giving me the power, talent, courage and opportunity to take on this research study and to persist and finish it to satisfaction. Without His blessings, grace and love this accomplishment would not have been possible. To my wonderful, loving parents, grandparents and sister, thank you for believing in me every step of the way, thank you for your constant support and creating the space I so dearly needed to complete this study. I would also like to express my deepest appreciation to Christo Krause, for supporting me in every way imaginable. Together you made the ultimate cheerleading squad and equipped me with positivity, food, and support. I thank them for putting up with me in difficult moments where I felt stumped and for goading me on to follow my dream of getting this degree. This would not have been possible without their unwavering and unselfish love and support given to me at all times. Without the continued support and motivation from everyone in my life, I would not have been able to make a success of this project. I would especially like to thank the following people and institutions that have contributed to this project: To my supervisor, Prof. -

ELEPHANT MANAGEMENT Contributing Authors

ELEPHANT MANAGEMENT Contributing Authors Brandon Anthony, Graham Avery, Dave Balfour, Jon Barnes, Roy Bengis, Henk Bertschinger, Harry C Biggs, James Blignaut, André Boshoff, Jane Carruthers, Guy Castley, Tony Conway, Warwick Davies-Mostert, Yolande de Beer, Willem F de Boer, Martin de Wit, Audrey Delsink, Saliem Fakir, Sam Ferreira, Andre Ganswindt, Marion Garaï, Angela Gaylard, Katie Gough, C C (Rina) Grant, Douw G Grobler, Rob Guldemond, Peter Hartley, Michelle Henley, Markus Hofmeyr, Lisa Hopkinson, Tim Jackson, Jessi Junker, Graham I H Kerley, Hanno Killian, Jay Kirkpatrick, Laurence Kruger, Marietjie Landman, Keith Lindsay, Rob Little, H P P (Hennie) Lötter, Robin L Mackey, Hector Magome, Johan H Malan, Wayne Matthews, Kathleen G Mennell, Pieter Olivier, Theresia Ott, Norman Owen-Smith, Bruce Page, Mike Peel, Michele Pickover, Mogobe Ramose, Jeremy Ridl, Robert J Scholes, Rob Slotow, Izak Smit, Morgan Trimble, Wayne Twine, Rudi van Aarde, J J van Altena, Marius van Staden, Ian Whyte ELEPHANT MANAGEMENT A Scientific Assessment for South Africa Edited by R J Scholes and K G Mennell Wits University Press 1 Jan Smuts Avenue Johannesburg 2001 South Africa http://witspress.wits.ac.za Entire publication © 2008 by Wits University Press Introduction and chapters © 2008 by Individual authors ISBN 978 1 86814 479 2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express permission, in writing, of both the author and the publisher. Cover photograph by Donald Cook at stock.xchng Cover design, layout and design by Acumen Publishing Solutions, Johannesburg Printed and bound by Creda Communications, Cape Town FOREWORD SOUTH AFRICA and its people are blessed with diverse and thriving wildlife. -

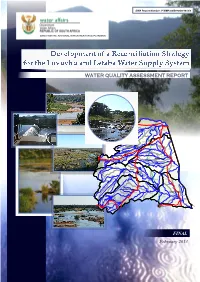

Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT

DWA Report Number: P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 DIRECTORATE: NATIONAL WATER RESOURCE PLANNING Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT u Luvuvh A91K A92C A91J le ta Mu A92B A91H B90A hu uv v u A92A Luvuvhu / Mutale L Fundudzi Mphongolo B90E A91G B90B Vondo Thohoyandou Nandoni A91E A91F B90C B90D A91A A91D Shingwedzi Makhado Shing Albasini Luv we uv dz A91C hu i Kruger B90F B90G A91B KleinLeta B90H ba B82F Nsami National Klein Letaba B82H Middle Letaba Giyani B82E Klein L B82G e Park B82D ta ba B82J B83B Lornadawn B81G a B81H b ta e L le d id B82C M B83C B82B B82A Groot Letaba etaba ot L Gro B81F Lower Letaba B81J Letaba B83D B83A Tzaneen B81E Magoebaskloof Tzaneen a B81B B81C Groot Letab B81A B83E Ebenezer Phalaborwa B81D FINAL February 2013 DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT REFERENCE This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Department of Water Affairs, South Africa, 2012. DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM: WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT Prepared by: Golder Associates Africa Report No. P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 Water Quality Assessment Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System Report DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Water Quality Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Department of Water Affairs (DWA) has identified the need for the Reconciliation Study for the Luvuvhu-Letaba WMA. -

Kruger National Park River Research: a History of Conservation and the ‘Reserve’ Legislation in South Africa (1988-2000)

Kruger National Park river research: A history of conservation and the ‘reserve’ legislation in South Africa (1988-2000) L. van Vuuren 23348674 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in History at the School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof J.W.N. Tempelhoff May 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Masters of Arts in the subject group History, School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle Faculty, North-West University. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. L. van Vuuren May 2017 i ABSTRACT Like arteries in a human body, rivers not only transport water and life-giving nutrients to the landscape they feed, they are also shaped and characterised by the catchments which they drain.1 The river habitat and resultant biodiversity is a result of several physical (or abiotic) processes, of which flow is considered the most important. Flows of various quantities and quality are required to flush away sediments, transport nutrients, and kick- start life processes in the freshwater ecosystem. South Africa’s river systems are characterised by particularly variable flow regimes – a result of the country’s fluctuating climate regime, which varies considerably between wet and dry seasons. When these flows are disrupted or diminished through, for example, direct water abstraction or the construction of a weir or dam, it can have severe consequences on the ecological process which depend on these flows. -

An Exploratory Study from the Letaba River Catchment Is My Own Work

ALLOCATION AND USE OF WATER FOR DOMESTIC AND PRODUCTIVE PURPOSES: AN EX PLORATORY STUDY FROM THE LETABA RIVER CATCHMENT T.G MASANGU FEBRUARY 2009 1 KEY WORDS Water allocation Water collection Domestic water use Agricultural water use Water management institutions Water services Water allocation reform Water scarcity Right to water Rural livelihoods. i ABSTRACT ALLOCATION AND USE OF WATER FOR DOMESTIC AND PRODUCTIVE PURPOSES: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY FROM THE LETABA RIVER CATCHMENT T.G Masangu M.Phil thesis, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape. In this thesis, I explore the allocation and use of water for productive and domestic purposes in the village of Siyandhani in the Klein Letaba sub-area, and how the allocation and use is being affected by new water resource management and water services provision legislation and policies in the context of water reform. This problem is worth studying because access to water for domestic and productive purposes is a critical dimension of poverty alleviation. The study focuses in particular on the extent to which policy objectives of greater equity in resource allocation and poverty alleviation are being achieved at local level with the following specific objectives: to establish water resources availability in Letaba/Shingwedzi sub-region, specifically surface and groundwater and examine water uses by different sectors (e.g. agriculture, industry, domestic, forestry etc.,); to explore the dynamics of existing formal and informal institutions for water resources management and water services provision and the relationship between and among them; to investigate the practice of allocation and use of domestic water; to investigate the practice of allocation and use of irrigation water. -

Kruger National Park

Kruger National Park The world-renowned Kruger National Park offers a wildlife experience that ranks with the best in Africa. Established in 1989 to protect the wildlife of the South African Lowveld, this national park is nearly 2 million hectares is unrivalled in the diversity of its life forms and a world leader in advanced environmental management techniques and policies. Truly the flagship of the South African National Parks, Kruger is home to an impressive number of species: 336 trees, 49 fish, 114 reptiles, 34 amphibians, 507 birds and 147 mammals. Man’s interaction with the Lowveld environment over many centuries is very evident in the Kruger National Park – from bushman rock paintings to majestic archaeological sites like Thulamela and Masorini. These treasures represent the cultures, persons and events that played a role in the history of the Kruger National Park and are conserved along with the park’s natural assets. Attractions and Activities There are so many creatures to see and sightings of rare species can be the highlight of your trip! Keep up to date with the movements of the wildlife in the Kruger National Park by consulting the sightings map at reception, it is updated daily! Five things to seek: The Big Five: Elephant, Buffalo, Leopard, Lion and Rhino The Little Five: Elephant Shrew, Buffalo Weaver, Leopard Tortoise, Ant Lion and Rhino Beetle Birding Big Six: Kori Bustard, Ground Hornbill, Lappet-faced Vulture, Martial Eagle, Pel’s Fishing Owl and Saddle-bill Stork Five Trees: Fever Tree, Baobab, Knob Thorn, Marula and Mopane Natural / Cultural Features: Jock of the Bushveld Route, Letaba Elephant Museum, Masorini Ruins, Albasini Ruins, Stevenson Hamilton Memorial Library and Thulamela (a late Iron Age stone walled site) Activities include morning and afternoon nature walks, morning and night game drives, bush braais, 4x4 and eco- trails, wilderness hiking trails and backpack hiking trails. -

KRUGER NATIONAL PARK © Lonelyplanetpublications Atmosphere All-Enveloping

© Lonely Planet Publications 464 Kruger National Park Almost as much as Nelson Mandela and the Springboks, Kruger is one of South Africa’s national symbols, and for many visitors, it is the ‘must-see’ wildlife destination in the country. Little wonder: in an area the size of Wales, enough elephants wander around to populate a major city, giraffes nibble on acacia trees, hippos wallow in the rivers, leopards prowl through the night and a multitude of birds sing, fly and roost. Kruger is one of the world’s most famed protected areas – known for its size, conserva- tion history, wildlife diversity and ease of access. It’s a place where the drama of life and death plays out daily, with up-close, action-packed sightings of wildlife almost guaranteed. One morning you may spot lions feasting on a kill, and the next a newborn impala strug- gling to take its first steps. Kruger is also South Africa’s most visited park, with over one million visitors annually and an extensive network of sealed roads and comfortable camps. For those who prefer roughing it, there are 4WD tracks and hiking trails. Yet, even when you stick to the tarmac, the sounds and scents of the bush are never far away. And, if you avoid weekends and holidays, or stay in the north and on gravel roads, it’s easy to travel for an hour or more without seeing another vehicle. KRUGER NATIONAL PARK KRUGER NATIONAL PARK Southern Kruger is the most popular section, with the highest animal concentrations and easiest access. -

Shingwedzi 20

N CARAVAN & OUTDOOR LIFE CARAVAN N ov EMBE R 2010 ove mb ER WIN: 2010 Sh 2x two-week holidays in KZN! IN gw ED z I • C A mp & Shingwedzi SCU b A 4x4 Eco-Trail • 13 BUSH CAMPING IN MOZ TENTS TENT TIP-OFF models • 20 g to choose from LA 20 13 m OROUS GLAMOROUS GADGETS g German engineering AD meets caravan style g ETS D Thaba Monaté E WWW.CARAVANSA.CO.ZA W Lake Eland Game Reserve E DIVE RIGHT IN! VI Fish River Diner Caravan Park E RESORTS Camp & SCUBA R San Cha Len R26.80 (incl. VAT) BUSH FEAST: bRAAIED ChICkEN & SLAp ChIpS OUTSIDE SA R23.50 VAT excl. DON'T GET SCAMMED! RISky INTERNET pURChASES 2010 TOP PRINT PERFORMER ON THE WAR Photos by Mark Samuel and Grant Spolander PATH Words by Mark Samuel Words 20 Caravan & Outdoor Life • November 2010 SHINGWEDZI ECO-TRAIL Adjacent to Kruger, across the Mozambique border, lies Parque Nacional do Limpopo – the Mozambique portion of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. The fences between the parks are slowly coming down, and the popularity of this destination is increasing steadily. The best way to experience the region is on the Shingwedzi 4x4 Eco-Trail. So, with a Conqueror hitched to our Toyota Hilux, we set off to see what this trail has to offer. The briefing before the trail commences lets you know exactly where you’re headed. here they were: ghostly grey South Africa’s Kruger National Park and time. It’s beautiful, untamed and wild – all behemoths moving stealthily Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park. -

Kruger Big 5 Geology Safari*

KRUGER BIG 5 GEOLOGY SAFARI* Wes Gibbons 2019 This guide describes a self-drive tour of Kruger National Park that provides the opportunity not only for abundant wildlife viewing but also to learn about the geology underlying the scenery of the savanna. Many people seem to visit Kruger obsessed with the intention of photographing the “Big 5” (buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion and rhinoceros), completely unaware that there is another Big 5 waiting to be enjoyed in the rocks. So here it is: a Holiday Geology Guide to Kruger National Park. It is something of an adventure. If you have never visited Kruger before, then you are in for a treat. The route has been carefully chosen to maximise wildlife and scenic geology viewing, although note that this is mostly car seat geology as you can only leave your vehicle in a very few designated areas, and then at your own risk. Kruger is a zoo in which the humans are restricted to confined spaces, not the other animals. Rock exposure is generally poor across the deeply weathered and magnificently ancient African land surface, although there are notable exceptions in some parts of the park. The varied and beautiful landscapes found in the park however are a direct expression of the underlying geology which impacts on the scenery, soils, ecology and therefore wildlife distribution. The rocks range from some of the oldest found on planet Earth to relatively young sediments and volcanic lavas produced when Africa split from Antarctica during Jurassic supercontinental break-up and the world’s oceans as we know them began to form. -

South African Memories Uidander Risings Or Resistances, and Long Before the Jameson Raid

South African Memories Uidander risings or resistances, and long before the Jameson Raid. It was taken to indicate that the policy of repression and control by force was the accepted doctrine of the ruling party, and of course there were many, especially among the older residents, who were unshaken in the belief that the old p,olicy of extending the South African Republic (the very sigIl!ficant title originally given to the Transvaal and always retained), would be pursued, and that more sinister evidence of this might be expected at any time. Long before the end of 1894 hints and rumours got about that there were to be other forts constructed with the idea of repelling any possible invasion by the British troops. How these rumours originated it is impossible to say. They were believed by many to be the true indications of the attitude of the Transvaal Government, but they were also almost invariably received with derision by the non-Boer .p,opulation on the grounds that the idea of an invasion by Bntish troops was such a preposterous absurdity that this coUld not possibly be the true reason for the projected forts. Experience of the British Government's attitude towards South Africa, its uncertainties and inconsistencies due to party changes Liberal and Conservative-had produced such an effect that I do not believe there was a serious person in Africa who contemplated the possibility of British troops invading the Transvaal. It fell to my lot to be responsible for the firm's business in Pretoria and the district. -

Rnr. WAR in SOUTH AFRICA

11(5 rnr. WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA JAMKS, Major H. E. R. : Army Medical Service Jomt, Mr. : sentenced for carrying on illicit reform work, vf 542 liquor traffic, '00, i 122 JAMES, Lieut. (R.N.): at Colenao, ii 442; at JOHANNESBURG : Spion Kop, lit 283, 286 Administration during early months of JAMES, Lieut. : at Lichtenburg, v 223 war, iv 149-52; after British occupation, vi JAMESON, Dr. A. : appointed Commissioner of 683-01, iv 497 Land* in Transvaal, vi 57 Begbie's factory manufactures ammuni- : Director General iii 82 ii iv 150 JAMESON, Surg.-Gen. Army tion, ; wrecked, 70, Medical Service, vi 02, 643 Boers approve Kruger's franchise pro- : 1 i JAMKSON, Dr. L. S. portrait, 150 ; Adminis- posals, 288 i trator of Rhodesia ; prevents Boer invasion, Bogus conspiracy May 16 '99, 301, 302 1891, 106 ; undertakes to smuggle rifles into Chamber of Mines President endeavours ] 53 i 141 Johannesburg, ; force on Transvaal to allay excitement. '94, ; protests a ,-i i MSI, i 121 border, 160 ; Reformers request his aid, liquor traffic, ; attitude on raid into Transvaal 235 163, -164 ; makes ; cap- dynamite monopoly, in of tured at Doornkop, 167 ; leader of Cape Chamber of Trade favour Chinese, Progressives, vi 192 ; forms ministry, 193 ; vil!9 appreciation of administration, 193; ad- Chamberlain, Mr. arrives, vi 80 ministrative difficulties, 194 ; efforts to enlist Civil administration municipal govern- support of Moderates, 194 ; review of ministry ment conferred by Kruger, 218 ; condemiifd 195 227 vl (1904-8), 193-5 ; resignation and defeat, ; by Uitlanders, ; organization, v 270, supports movement for South African Union, 15, 16 iii 210 ; services at Convention, 214 ; suggests Clothing factory started by Boers, 82 title for Orange River Colony, 217 Commando see under REOIMENTA i.