Aphrodite Pandemos and the Hippolytus of Euripides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Aphrodite on a Ladder

APHRODITE ON A LADDER (PLATES 17-19) N JULY OF 1981, in Byzantinelevels above and west of what was soonto be identified as the Stoa Poikile, the excavatorsof the Athenian Agora found two joining fragmentsof a Classical votive relief (P1. 17:a).1 The relief is framed by simple moldings: taenia and ovolo at top and a plain band at the right side. In the pictorial field is preservedthe head of a young woman carved in low relief. She gazes down to the left at a vessel raised in her right hand. Her head is coveredby a short veil. Above and behind the veil are two rungs and the vertical supports of a ladder whose upper end disappearsbehind the frame. Although frag- mentary and weathered, the relief provides a precious document for the study of Classical relief sculpture, and its unusual iconographygives a valuable clue to the identity of one of the deities worshiped in the area. Most of the figure'sprofile is broken away, but the carefully carvedlines of the lips and eye show that the sculptor took pains to give her delicate features. Her hair, where it ap- pears below the veil, is mostly worn away. Along the side of her face appear waves of hair with a scallopedcontour. No trace of her ear is preserved.It was either very small or hidden beneath her hair. Folds of the veil cross her head in bifurcating linear patterns of rounded ridges. Below her hair two folds fall down along her neck, while others, from the hidden right side of her head, blow out behind in sweeping curves. -

William Manning the DOUBLE TRADITION of APHRODITE's

William Manning THE DOUBLE TRADITION OF APHRODITE'S BIRTH AND HER SEMITIC ORIGINS In contrast to modem religion, there was no "church" or religious dogma in the ancient world. No congress of Bishops met to decide what was acceptable doctrine and what was, by process of elimination, heresy. Matters of faith could be exceedingly complex and variable. The gods evolved over time and from place to place, dividing and diverg ing, so that many simultaneous beliefs were possible. Most students of Greek mythology are familiar with the "pairing" of certain gods and goddesses in the pantheon. Zeus is associated with his wife Hera, and Apollo with his sister Artemis, for example. It is believed that this reflects the introduction of male Sky Gods by Indo European invaders, which were allowed to co-exist with the Earth Mother Goddesses already worshipped by indigenous populations. Some scholars believe that Posiedon and Zeus are manifestations of the same Inda-European deity brought to the Greek mainland by succes sive waves of immigrants. Other aspects of mythological duality include the presence of apparently contrasting attributes within the same deity, and the allocation of opposing aspects of the same activity to more than one God. The example most often cited is Athena, Goddess of Wisdom. While she was patroness of culture and learning, she was always depicted in armor and championed the "positive" aspects of war such as courage and loyalty. The grouping of these attributes would seem strange to us today. Most Classics students will immediately point out that it is Ares who was recognized as the God of War. -

Peitho, Dolos, and Bia in Three Late Euripidean Tragedies

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-30-2021 2:00 PM Peitho, Dolos, and Bia in Three Late Euripidean Tragedies Christian Bot, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Brown, Christopher G., The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Classics © Christian Bot 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Bot, Christian, "Peitho, Dolos, and Bia in Three Late Euripidean Tragedies" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7778. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7778 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii Abstract The themes of peitho (persuasion), dolos (trickery), and bia (violence or physical force) are central to the action of the three late Euripidean tragedies that I explore: Iphigenia in Tauris, Iphigenia in Aulis, and the Bacchae. I examine how these themes influence characters' interpersonal relations, drive plot development, and determine the "mood" of each play in terms of a spectrum from optimism to pessimism. Summary for Lay Audience I examine three plays by the Ancient Greek tragedian Euripides (ca. 480-406 BC), each of them written during the later stages of his career: Iphigenia in Tauris (ca. 412 BC), Iphigenia in Aulis, and the Bacchae (both produced posthumously in 405 BC). -

Aeschylean Drama and the History of Rhetoric

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Aeschylean Drama and the History of Rhetoric Allannah K. Karas The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2111 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ΑESCHYLEAN DRAMA AND THE HISTORY OF RHETORIC by ALLANNAH KRISTIN KARAS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 ALLANNAH KRISTIN KARAS All Rights Reserved ii AESCHYLEAN DRAMA AND THE HISTORY OF RHETORIC by Allannah Kristin Karas This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Dee Clayman Chair of Examining Committee Date Dee Clayman Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Dee Clayman Joel Lidov Lawrence Kowerski Victor Bers (Yale University) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Aeschylean Drama and the History of Rhetoric by Allannah Kristin Karas Advisor: Professor Dee Clayman This dissertation demonstrates how the playwright Aeschylus contributes to the development of ancient Greek rhetoric through his use and display of πειθώ (often translated “persuasion”) throughout the Oresteia, first performed in 458 BCE. In this drama, Aeschylus specifically displays and develops πειθώ as a theme, a goddess, a central principle of action, and an important concept for his audience to consider. -

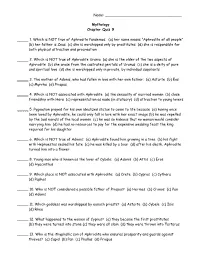

Mythology Chapter Quiz 9

Name: __________________________________ Mythology Chapter Quiz 9 _____ 1. Which is NOT true of Aphrodite Pandemos: (a) her name means “Aphrodite of all people” (b) her father is Zeus (c) she is worshipped only by prostitutes (d) she is responsible for both physical attraction and procreation _____ 2. Which is NOT true of Aphrodite Urania (a) she is the older of the two aspects of Aphrodite (b) she arose from the castrated genitals of Uranus (c) she is a deity of pure and spiritual love (d) she is worshipped only in private, by individual suppliants _____ 3. The mother of Adonis, who had fallen in love with her own father: (a) Astarte (b) Eos (c) Myrrha (d) Priapus _____ 4. Which is NOT associated with Aphrodite (a) the sexuality of married women (b) close friendship with Hera (c) representation as nude (in statuary) (d) attraction to young lovers _____ 5. Pygmalion prayed for his own idealized statue to come to life because (a) having once been loved by Aphrodite, he could only fall in love with her exact image (b) he was repelled by the bad morals of the local women (c) he was so hideous that no woman would consider marrying him (d) he had no resources to pay for the expensive wedding feast the king required for his daughter _____ 6. Which is NOT true of Adonis: (a) Aphrodite found him growing in a tree (b) his fight with Hephaestus sealed his fate (c) he was killed by a boar (d) after his death, Aphrodite turned him into a flower _____ 8. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2000

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 16 | 2003 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2000 Angelos Chaniotis and Joannis Mylonopoulos Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/832 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.832 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2003 Number of pages: 247-306 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis and Joannis Mylonopoulos, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2000 », Kernos [Online], 16 | 2003, Online since 14 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/832 Kernos Kemos, 16 (2003), p. 247-306. Epigraphie Bulletin fOl" Gt"eek Religion 2000 (EBGR 2000) The 13th issue of the Epigrapbic Bulletin for Greek Religion presents a selection of those epigraphic publications from 2000 that contribute to the study of Greek religion ancl its cultural context (Oriental cuIts, ]uclaism, Early Christianity); we have also filled some of the remaining gaps from earlier issues (especially BBGR 1999). As in earlier bulletins, we have also incluclecl a selection of papyrological publications, especially with regard to the stucly of ancient magic. \V'e were unable to include in this issue several important new publications, such as the first volume of the Samian corpus (cf nO 69) or the corpus of the published inscriptions of Philippi (P. PILHOFER, Fbilippi. Band II. Katalog der Inscbriften von Fbi/ippi, Tübingen, 2000), but we plan to present them together with several other books and articles published in 1998-2000 - in the next issue of the BBGR. -

Greek Devotional Images: Iconography and Interpretation in the Religious Arts

Greek Devotional Images: Iconography and Interpretation in the Religious Arts DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Katherine A. Rask Graduate Program in History of Art The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Mark D. Fullerton, Adviser Timothy J. McNiven Sarah Iles Johnston Hugh B. Urban Copyright by Katherine A. Rask 2012 Abstract This dissertation concerns the uses of iconography, visual culture, and material culture in the study of Greek religion. I draw on methods and theoretical frameworks from outside the discipline in order contextualize the study of images and symbols in larger discourses and to introduce the most recent developments in scholarship. To better understand the religious aspects of Greek experience, this dissertation presents a mixture of intellectual history, historiography, and methodological critique. I provide an interdisciplinary overview of symbol theory and approaches to signs, the deep-seated interweaving of theological and artistic concerns in occultist traditions and 19th century scholarship, and iconographic methodologies employed by Classical studies and archaeology. Several themes repeatedly appear throughout the discussion, including the theoretical relationships between material culture and religion and the perceived dichotomy between phenomenological responses and interpretation. By exploring these topics, it becomes clear that approaches to religion in ancient Greece need to be adapted to better account for visual and material culture. Despite most emphasis on public, ritual-centered aspects, images and objects attest to private encounters with divinities. Based on comparative analysis, I argue that the religious experience of ancient Greeks exhibits many elements of devotionalism, a religious phenomenon developed by Robert Orsi. -

Paul Epstein, the Treatment of Poetry in the Symposium of Plato

Animus 4 (1999) www.swgc.mun.ca/animus The Treatment Of Poetry In The Symposium Of Plato Paul Epstein [email protected] The Symposium of Plato presents the demythologizing of the god Eros, that is, the rational clarification of his nature. At a dinner to celebrate the victory of the tragic poet Agathon in the Theatre, the guests all give speeches in honour of the god. Of the initial speakers, neither the comic poet Aristophanes nor the tragic poet Agathon can give more than a partial account of his nature, and it remains for Socrates, who has himself been taught the doctrine, to define it as the human desire for the eternal possession of the Beautiful. This done, the speech of Alcibiades shows the limits of Socrates' personal realization of this teaching and compels him to indicate the necessity of a new poetry, at once tragic and comic, that can more effectually present this philosophical view to the City. The views of the two poets express dividedly what Socrates, as taught by a certain Diotima, can bring into one view. While Aristophanes sees in eros an impetus toward a restored human wholeness, Agathon identifies it with the universal Beauty. The view of each poet is meant by Plato to represent, moreover, the general tendency of his genre; independently of philosophy, then, both Tragedy and Comedy have gathered up the many gods and heroes of the poetical religion of the Greeks into a single view of divinity and humanity, respectively. Thus the philosophical treatment of eros both arises in relation to poetry and is at once the correction and completion of poetry. -

Servants of Peitho: Pindar Fr.122 S. Anne Pippin Burnett

Servants of Peitho: Pindar fr.122 S. Anne Pippin Burnett O ILLUSTRATE THE PART played by Corinthian prosti- tutes in that city’s worship of Aphrodite, Athenaeus long ago set down bits of a song that he seems to have T 1 found in Chamaeleon’s On Pindar (Athen. 13.573B–574B). This fragment (Pindar fr.122 S.) has gained a certain recent notoriety, for it is regularly cited as evidence for or against the existence of “temple prostitution” in classical Greece.2 Never- theless, the song itself has been almost unanimously dismissed as the clumsy work of a poet embarrassed by his assigned subject. It is time to give these few lines a close reading, taking them as Pindaric and meant to please a particular small audi- ence in early fifth-century Corinth. 1 Chamaeleon is explicitly cited only for a Cornthian custom of inviting prostitutes to join in civic prayers to Aphrodite (573C), but he was most probably the source of the lines from Pindar and he seems to have identified the favor received from the goddess as the Olympic victory celebrated in Pindar’s Ol. 13 (Athen. 573F) though nothing within fr.122 S. fixes this as fact. On Chamaeleon’s general accuracy, see F. Wehrli, Die Schule des Aristoteles2 IX (Basel/Stuttgart 1957) 82–83. 2 The most recent and extensive treatment is that of S. Budin, The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity (Cambridge 2008) 112–152, an earlier version of which appeared in C. Faraone and L. McClure (eds.), Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World (Madison 2006) 84–86. -

{PDF} the Symposium Ebook, Epub

THE SYMPOSIUM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Plato | 128 pages | 25 Aug 2005 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141023847 | English | London, United Kingdom The Symposium - IMDb From Coraline to ParaNorman check out some of our favorite family-friendly movie picks to watch this Halloween. See the full gallery. Two English stage actors, Hugo and Jago, have an artistic difference while rehearsing a radio play. This evolves rapidly into a huge fracas, and spills onto a West End side street. Naturally, this draws a horde or passersby, including an American bystander, who elects to be the peacemaker. Things soon deteriorate from the scholarly to the brutal, even physical, and long held personal and societal prejudices surface. Class, racial origins, and history are harshly debated. Then Hugo, the posh one, proclaims his African ancestry, which bombshell causes a puzzled Jago to accost an African Traffic warden for verification, thus opening a third front to his quarrel with Hugo. There is a reversal of roles, with the posh Hugo championing liberal causes, the working class Jago becoming more and more entrenched as a xenophobe, and the traffic warden boasting an exemplary academic and social pedigree, despite his job. Unbeknownst to Jago, however, this entire 'symposium' is meant either to be his Written by Ishmael Annobil. Looking for something to watch? Choose an adventure below and discover your next favorite movie or TV show. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. Official Sites. Company Credits. Technical Specs. Plot Summary. Plot Keywords. External Sites. -

The Politics of Weddings at Athens: an Iconographic Assessment

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading LEEDS INTERNATIONAL CLASSICAL STUDIES 4.01 (2005) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Amy C. Smith The politics of weddings at Athens: an iconographic assessment AMY C. SMITH (UNIVERSITY OF READING) ABSTRACT: Despite recent scholarship that has suggested that most if not all Athenian vases were created primarily for the symposium, vases associated with weddings constitute a distinct range of Athenian products that were used at Athens in the period of the Peloponnesian War and its immediate aftermath (430-390 BCE). Just as the subject matter of sympotic vases suggested stories or other messages to the hetaireia among whom they were used, so the wedding vases may have conveyed messages to audiences at weddings. This paper is an assessment of these wedding vases with particular attention to function: how the images reflect the use of vases in wedding rituals (as containers and/or gifts); how the images themselves were understood and interpreted in the context of weddings; and the post-nuptial uses to which the vases were put. The first part is an iconographic overview of how the Athenian painters depicted weddings, with an emphasis on the display of pottery to onlookers and guests during the public parts of weddings, important events in the life of the polis. The second part focuses on a large group of late fifth century vases that depict personifications of civic virtues, normally in the retinue of Aphrodite (Pandemos). The images would reinforce social expectations, as they advertised the virtues that would create a happy marriage—Peitho, Harmonia (Harmony), and Eukleia (Good Repute)—and promise the benefits that might result from adherence to these values—Eudaimonia and Eutychia (Prosperity), Hygieia (Health), and Paidia (Play or Childrearing).