Bellows: the Matusewitch Family Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

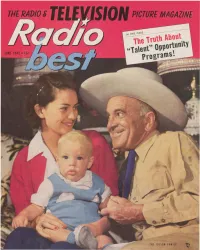

Radio Best 4906.Pdf

___THE JOLSn fAMllt Are BOU interested in800d books .......... EACH DISTINGUISHED IN ITS FIELD in Fiction.- Biographg ~ Histof21.-Science-The American Scene here are two reasons why you should belong to the Book Find Club. The first is the Club's consistent record for selecting the outstanding new books. The second is the Club's special membership price of only $1.65 a book, an average saving to members of more than 50 percent on their book purchases. The books featured on this page are representative of the selections the Book Find Club distributes to its members. Whether you prefer novels like THE NAKEDANDTHE DEAD by orman MailerandCRY, THEBELOVE~' COU TRY by Alan Paton; or biographies such as LI COLN'S HER • DO by David Donald; or historical works like THE AGE OF JACKSON by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.; or scientific books like FEAR, WAR AD THE BOMB by P. M. S. Blackett, who was recently awarded the obel Prize; or books on the American Scene such as A MASK FOR PRIVI LEGE by Carey McWilliams and THE WAR LORDS OF WASHI GTON by Bruce Catton-Book Find Club selections arc always books worth read· ing and worth keeping for your permanent library. ... at B~ Savin8s 10You! ku can begin your membership in the Bool.. Find Club now with anyone of the distmguished selections pictured on this page. In addition, as a new member. you may choose a FREE enrollment book from among tho~ listed in the coupon below. The publishers' list prices of these selections range from $2.50 to S5.oo, but members pay only the special membership price of $1.65 a book. -

U.S. Entry Into WWII and Changes in Dissention Attitude the Basics Time Required 2-3 Class Periods Subject Areas 11Th Grade Hist

U.S. Entry into WWII and Changes in Dissention Attitude The Basics Time Required 2-3 class periods Subject Areas 11th Grade History (A.P.) The Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945 Common Core Standards Addressed: Writing Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies 6-12 Author Martha Graham (2004) The Lesson Introduction The songs “Ballad of October 16” and “What Are We Waitin’ On?” both sung by the folk group Almanac Singers, express opposite sentiments regarding war. “Ballad of October 16” was written in 1940 to protest FDR’s movement toward war. The passage of a conscription law in September 1940 was evidence to Communist Party members, which included many members of the Almanac Singers, that FDR was lying when he had vowed to stay out of the European war. As a result of this scathing criticism, FBI files were opened on Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie and they were followed for decades. “What Are We Waitin’ On?” written in 1942, demonstrates an abrupt about-face that can be explained only in the context of the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Guiding Questions Why did the United States enter World War II? How would this decision affect the lives of American citizens? Learning Objectives 1. Students will describe the causes for dissention prior to US involvement in WWII. 2. Students will explain the causes for US entry into the war. 3. Students will synthesize the change in the attitudes in some dissenters during the war. Preparation Instructions Songs used in this lesson: “What Are We Waitin’ On?” “Ballad of October 16” “Citizen CIO” Songs used in lesson: • “Ballad of October 16” (1940) performed by Almanac Singers on That’s Why We’re Marching: World War II and the American Folk Song Movement, Smithsonian Folkways, 1996. -

April, 2002 Vol 37, No.4

April, 2002 vol 37, No.4 April 3WedFolk Open Sing; 7pm in Brooklyn 5 Fri Lorraine & Bennett Hammond; Music at Metrotech, 8pm 6 Sat Lorraine & Bennett Hammond Workshops - see p.7 7 Sun Sea Music Concert: Howie Leifer's Homesick Sailor Puppet Theatre. +NY Packet, 3 pm 7 Sun Sunnyside Song Circle, 2 pm at Joel Landy’s 8 Mon NYPFMC Exec. Board Meeting, 7:15pm at the club office, 450 7th Ave, #972, info (718) 575-1906 11 Thur Riverdale Sing, 7:30-10pm, Riverdale Prsby. Church. 14 Sun Old Time String Band Get-together; 1:30pm in Bklyn 17 Wed Traditional Music Open Mike & Folk Music Jam; loca- tion tba; 7 pm. 18 Thur Finest Kind, Advent Church, 8pm ☺ 21 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St.Bartholomew’s; 2:30 pm 27 Sat Peggy Seeger, Advent Church, 8:30pm, Note Time! ☺ 28 Sun Peggy Seeger Workshop; see page 7 May 1WedNewsletter Mailing; at Club office, 450 7 Ave, #972, 7 pm 1WedFolk Open Sing; 7pm in Brooklyn 3 Fri Triboro; Music at Metrotech, 8 pm in Brooklyn 5 Sun Gospel & sacred Harp Sing; 3 pm in Queens 5 Sun Sea Music Concert: Don Sineti + NY Packet, 3 pm at South Street Seaport 12 Sun Old Time String Band Get-together; 1:30pm in Bklyn 13 Mon NYPFMC Exec. Board Meeting, 7:15pm at the club office, 450 7th Ave, #972, info (718) 575-1906 15 Wed Traditional Music Open Mike & Folk Music Jam 16 Thur Riverdale Sing, 7:30-10pm, Riverdale Prsby. Church. 19 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St.Bartholomew’s; 2:30 pm Details Inside - Table of Contents on page 9 The Club’s web page: http://www.folkmusicny.org FOLK OPEN SING; Wednesdays, April 3 & May 1; 7pm Join us on the first Wednesday of each month for an open sing. -

The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965

1 The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965 By Bobby Ellerbee and Eyes of a Generation.com Preface and Acknowledgements This is the first known chronological listing that details the CBS television studios in New York City. Included in this exclusive presentation by and for Eyes of a Generation, are the outside performance theaters and their conversion dates to CBS Television theaters. This compilation gives us the clearest and most concise guide yet to the production and technical operations of television’s early days and the efforts at CBS to pioneer the new medium. This story is told to the best of our abilities, as a great deal of the information on these facilities is now gone…like so many of the men and women who worked there. I’ve told this as concisely as possible, but some elements are dependent on the memories of those who were there many years ago, and from conclusions drawn from research. If you can add to this with facts or photos, please contact me, as this is an ongoing project. (First Revision: August 6, 2018). Eyes of a Generation would like to offer a huge thanks to the many past and present CBS people that helped, but most especially to television historian and author David Schwartz (GSN), and Gady Reinhold (CBS 1966 to present), for their first-hand knowledge, photos and help. Among the distinguished CBS veterans providing background information are Dr. Joe Flaherty, George Sunga, Dave Dorsett, Allan Brown, Locke Wallace, Rick Scheckman, Jim Hergenrather, Craig Wilson and Bruce Martin. -

DOCUMENT RESUME SO 005 429 TITLE a Teacher's Guide To

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 073 036 SO 005 429 TITLE A Teacher's Guide to Folksinging. A Curriculum Guide for a High School Elective in Music Education. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Bureau of Secondary Curriculum Development. PUB DATE 172] NOTE 33p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Cultural Awareness; Folk Culture; *Music; Musical Instruments; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Resource Guides; Secondary Grades; Singing; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Folksinging ABSTRACT The material in this teacher's guide fora high school elective course may be used in a variety of curriculum designs--from a mini elective to a full year course. The rationale section explains that folksinging can be a valuable activity in the classroom by: 1) presenting a mirror for the student's personality and by being a useful tool for individual development; 2) allowing students to "act out" their impressions insong and thus allowing them to gain important insights and an empathy with people and situations that might never be gained through direct experience; 3) making it possible for students to transverse history, feel the pain of social injustice, lessen inhibitions, fulfill emotional needs, test creative talent, be given an outlet to their idealisticenergy, and find infinite pleasure in performing good music. Sections included in the guide are: Introduction: Philosophy and Rationale, InstructionAl Guidelines, Comments Concerning Equipment (folk instruments), and, A Representative Sampling of Multimedia Resource Materials (which includes books and periodicals, films, records, filmstrips and record sets, and record collections).Another document in this series is Teaching Guitar (SO 005 614). (Author/OPH) FD 07303t'; 1. -

Folkways Records and the Ethics of Collecting: Some Personal Reflections1

Labelle: Reflections on the Passing of Allan Kelly 110 Folkways Records and the Ethics of Collecting: Some Personal Reflections1 MICHAEL ASCH Abstract: In this article, anthropologist Michael Asch recounts fascinating histories surrounding the genesis of Folkways Records, focusing on aspects of diversity, selection, and ethics. He illus- trates the discussion by invoking pertinent anthropological and folklore paradigms. olkways Records and Service Corporation, unarguably the most unique Frecording company ever to exist, was founded in 1948 by my father, Moses Asch. In the 38 years of operation, between 1948 and 1986 when my father died, Folkways produced over 2100 albums, an average of more than one per week – a feat accomplished with a labour force that never exceeded a handful of people. Furthermore, he rarely took a record out of print, and then never for commercial reasons. It was a record catalogue of staggering diversity and eclecticism. To give you a sense of the breadth of this collection, here are just a few of the familiar names found on the label: Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Phil Ochs, Jean Ritchie, Mary Lou Williams, Ella Jenkins, The Carter Family, Lucinda Williams, Janis Ian, Martin Luther King, Bertold Brecht, Margaret Mead, Langston Hughes, W. E. B. DuBois, and Bob Dylan (under the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt). Significantly, Folkways also included a vast repertoire of lesser-known artists important to such genres as blues, bluegrass, old-time, and country, and contains many of the most iconic songs in the American -

UAW Stamp, and I’M UAW Too, I’M Proud to Say.”

Document 8.1 U.A.W. – C.I.O. 1942 I was hangin’ ‘round a defense town one day, one day, When I thought I overheard a soldier say, soldier say: “Every tank in my camp Has that UAW stamp, And I’m UAW too, I’m proud to say.” CHORUS: It’s that UAW-CIO makes the army roll and go Turnin’ out the jeeps and tanks, the airplanes ev’ry day It’s that UAW-CIO makes that army roll and go Puts wheels on the USA I was there when the union came to town. I was there when old Henry Ford went down. I was standing by Gate Four When I heard the people roar: They ain’t gonna kick the auto workers ‘round. CHORUS I was there on that cold December day, When we heard about Pearl Harbor far away. I was down on Cadillac Square When the union rallied there To put those plans for pleasure cars away. CHORUS There’ll be a union label in Berlin, When the union boys in uniform march in. And rolling in the ranks There’ll be UAW tanks Roll Hitler out, and roll the union in. Lyrics written by Butch Hawes and Bess Lomax Hawes in 1942. First recorded in 1944 by The Union Boys, as part of Asch Records’ issue of “Songs For Victory.” Text and audio of Lyrics at: Labor Arts website. http://www.laborarts.org/exhibits/laborsings/song.cfm?id=20 [accessed 8/3/2016] LAWCHA: Teaching Labor’s Story. Document 8.1 DOCUMENT 8.1 Document Title: U.A.W.– C.I.O. -

Ted Mack Videos TED Stands for Torrent Episode Downloader, a Multiplatform Application Developed in Java to Help You Find the Torrent Files for All Your Fave TV Shows

Ted For Mac TED.com features interactive transcripts for most videos in our library. To access a transcript, click the Transcript button underneath the video player. If the talk has been translated into a certain language, you'll be able to view the transcript in that language by clicking the drop-down menu and selecting it. The season finale of Ted Lasso is now available to watch on Apple TV+. The show stars Jason Sudeikis playing a character originally conceived back in 2013 as part of an advertising campaign for. The official TED app presents more than 1600 talks from some of the world's most fascinating people: education radicals, tech geniuses, medical mavericks, business gurus, and music legends. New talks are posted every day from TED events around the world. 1. Ted Macarthur 2. Ted Mack Performers Archives 3. Ted Download For Mac 4. Red For Mac 5. Ted Mack Videos TED stands for Torrent Episode Downloader, a multiplatform application developed in Java to help you find the torrent files for all your fave TV shows. (Note that you'll obviously have to use a BitTorrent client to download the episodes.) CSI in its many different versions, Beti, Eureka, Bones, The Closer, Dexter, House, Heroes, Kyle XY, Prison Break, Grey's Anatomy, or The Simpsons are just a few examples of the shows you can download with TED. The episodes are sorted by season and you can check the availability of an episode with the progress bar right next to its name. We recommend you use Transmission or Vuze as BitTorrent clients for Mac. -

News from Library of Congress: 2010

NEWS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MOUG/MLA 2010 The News from the Library of Congress this year includes reports from the major Library units concerned with music and sound recording materials: Music Division, National Audio-Visual Conservation Center/Packard Campus, the Policy and Standards Division, and the American Folklife Center. Reports from other Library units which may contain concerns of importance to the music library community (e.g., Copyright Office, Preservation Directorate, Technology Policy Directorate) may be found in the ALA Midwinter report on the Library’s website: http://www.loc.gov/ala/mw-2010-update.html MUSIC DIVISION --Reported by Sue Vita, Joe Bartl, Mark Horowitz, Karen Lund, and Steve Yusko Since the last MLA meeting in Chicago the Music Division made significant progress in pursuing its primary goal, which is to improve access, both on site and online, to its collections. This was the first year that the two Music Bibliographic Access teams were fully integrated into the Music Division, and the success of this move can be seen both in the numbers of materials now accessible, and in the breadth of cataloging and metadata projects completed and in progress. Ninety-three entries for special collections were added to the Performing Arts Encyclopedia (PAE), bringing the total to 296. More than 33,900 master digital files were added to the PAE, including four new special presentations. More than 12,000 collection items were cataloged. Metadata was created for 13 previously “hidden” collections. The RIPM project has resulted in 89,509 pages from 225 volumes of 45 periodical titles scanned, to be made available online in the Performing Arts Reading Room, and after 3 years, available on our web sites. -

The Inventory of the Tom Glazer Collection #932

The Inventory of the Tom Glazer Collection #932 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Glazer, Tom #932 1982-1985 Preliminary Listing I. Correspondence. Box 1 A. Files may include printed materials, photographs .. 1. "1942-1961 Plus Scrapbook I." [F. 1] 2. "1962-1966 Plus Scrapbook II." [F. 2-3] 3. "July, 1966-1969." [F. 4-5] 4. "Mid., 1969-1972." [F. 6-7] 5. "1973-1974." [F. 8] 6. "1975-July, 1976," notables include: [F. 9] a. Peck, Gregory. TLS to Robert Snyder, 2/27/75; photocopy. 7. "June, 1976 - Aug. 1977." [F. 10] 8. "Nov., 1977 - Dec., 1978." [F. 11] 9. "1979." [F. 12] 10. "1980." [F. 13] Box2 11. "1981." [F. 1] 12. "1981-1982." [F. 2-3] 13. "Letters, 1983 - Received." [F. 4-5] 14. "Personal Letters and Carbons," sub-files include: a. "1947-1968." [F. 6] b. "June, 1974 - Sept., 1980." [F. 7] c. "Jan., 1970 - Dec., 1977 (Carbon From TG)." [F. 8] d. "Mostly 1977, 1980, 1981," includes one item each from 1976,1971. [F.9] 15. "Prominent People," notables include: [F. 10-1 l] a. Kazan, Elia. 10 TLS: 11/14/56, 7/16/57, 7/24/57, 2/11/58, 10/4/67, 4/22/68, 1/27 /70, 3/2/70, 9/25/80, 5/18/81. b. McGovern, George. Telegram, 10/9/72. c. Rockwell, Norman. TLS, 1/20/76. d. Gambling, John. TLS, 12/6/78. e. Ritchie, Jean. ALS, 6/15/73. f. Cheever, Mary. 2 TLS, n.d.; 7 postcards, 1957, 8/7/70, 1/29/77, 9/8/77, 1977, n.d. -

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT Library of Congress Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2009 (October 2008-September 2009) The American Folklife Center (AFC), which includes the Veterans History Project (VHP), had another productive year. Over half a million items were acquired, and over 127,000 items were processed by AFC's archive, which is the country’s first national archive of traditional culture, and one of the oldest and largest of such repositories in the world. VHP continued making strides in its mission to collect and preserve the stories of our nation's veterans, acquiring 7,408 collections (25,267 items) in FY2009. The VHP public database provided access to information on all processed collections; its fully digitized collections, whose materials are available through the Library’s web site to any computer with internet access, now number over 7,000. Together, AFC and VHP acquired a total of 524,363 items in FY2009, of which 105,939 were Non-Purchase Items by Gift. AFC and VHP processed a total of 127,003 items in FY2009, and cataloged 21,856 items. AFC and VHP attracted well over a million visits to the Library of Congress website. ARCHIVAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS KEY ACQUISITIONS George Pickow and Jean Ritchie Collection (AFC 2008/005; final increment): The latest addition to this collection includes approximately 150 linear feet of manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera, as well as over 400 audiotapes. The material extensively documents the long career of Jean Ritchie, the celebrated singer of traditional Appalachian ballads. As well, it includes documentation of the folklore of the Cumberland Mountains, and related Old World traditions in the British Isles, that was created by Ritchie and her husband, George Pickow, a professional documentary filmmaker and photographer. -

Tbcproductlist Radiotv IV

CONTENTS Teresa’s Singles Section I Teresa’s Collections Section II Other & Multi-Artist Products featuring Teresa Brewer Section III Radio, TV & Movie Appearances by Teresa Brewer Section IV Sheet Music of Teresa Brewer Songs Section V Reprinted from the Teresa Brewer Center, http://www.teresafans.org 6/7/2019 Section IV CONTENTS Radio, TV & Movie Appearances by Teresa Brewer Page Radio Shows (by Date) IV-2 TV & Video (by Date) IV-4 Motion Picture IV-11 Reprinted from the Teresa Brewer Center, http://www.teresafans.org 6/7/2019 Page IV-1 Teresa Brewer Product List – Section IV / Radio Appearances by Teresa (by date) Radio Appearances by Teresa Brewer: (BY DATE) • Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour (1938) • Let's Go to Town - The National Guard Shows (1953) Original performance: Nov 1938 (1953; Radio) [D1790] The format for the Original Amateur Hour on TV was • Armed Forces Radio (1958) taken directly from radio days' Major Bowes' (1958; Radio LP CH-150 / SSL-11334 ) [D0295] Amateur Hour. Major Bowes presided over a weekly parade of mimics, kazoo players and one- • Army Entertainment Program (1958) man bands with genial good humor. A year and a (1958; Radio LP) [D0301] half after the Major's death, the show was transferred from radio to television, with Ted Mack • Army Bandstand as its host. Listeners -- and viewers when the show (1960; Radio Program #131 ) [D0300] switched to television -- voted for their favorites by telephone or postcard, with the finalists being • Here's To Veterans - "Widow's Pensions" awarded with scholarships. On an evening in Nov (1960; Radio Program #739 ) [D1270] 1938, little Teresa Brewer appeared on Major Bowes' radio show.