Queering an Icon: the Legend of Zelda and Inclusive Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero's Experience in the Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt in Fulfillment Of

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt In fulfillment of M.M. in Music Theory Supervised by Dr. Benjamin Graf, Dr Graham Hunt, and Micah Hayes May 2019 The University of Texas at Arlington ii ABSTRACT Jillian Wyatt: The Journey of a Hero Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Under the supervision of Dr. Graham Hunt The research in this study explores concepts in the music from select games in The Legend of Zelda franchise. The paper utilizes topic theory and Schenkerian analysis to form connections between concepts such as adventure in the overworld, the fight or flight response in an enemy encounter, lament at the loss of a companion, and heroism by overcoming evil. This thesis identifies and discusses how Koji Kondo’s compositions evoke these concepts, and briefly questions the reasoning. The musical excerpts consist of (but are not limited to): The Great Sea (Windwaker; adventure), Ganondorf Battle (Ocarina of Time; fight or flight), Midna’s Lament (Twilight Princess; lament), and Hyrule Field (Twilight Princess; heroism). The article aims to encourage readers to explore music of different genres and acknowledge that conventional analysis tools prove useful to video game music. Additionally, the results in this study find patterns in Koji Kondo’s work such as (to identify a select few) modal mixture, military topic, and lament bass to perpetuate an in-game concept. The most significant aspect of this study suggests that the music in The Legend of Zelda reflects in-game ideas and pushes a musical concept to correspond with what happens on screen while in gameplay. -

The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess HD I Adore Snowpeak

The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess HD Play Journal Entries Stagger Lanayru79 03/13/2016 2:10 PM I adore Snowpeak Ruins, but I think I said enough about it on the log of my first playthrough. I'll pick up part two of a more story oriented journal here, right-handed blue-hearted style ... WARNING: Unmarked spoilers will appear in the comments. It's been so long since I came to the cannon tutorial room before having the Ball and Chain. Heh. E Yeah! e 29 r 102 D Advertisement Share this Post 1 Tweet 2 Share Embed Comment Stagger 03/13/2016 2:30 PM I concluded my last post discussing how crafty Ashei and Yeto's roles were in getting here, disarming the battle w/ a snow beast notion. Yeta's transformation into Blizetta is the payoff. It's a gorgeous fight in HD, and the creepy organ work suits it perfectly. So is this King Zora's mansion? I just noticed that the goat portraiture is from inside the house, but pictures of the City in the Sky? E Yeah! e 2 D Stagger 03/13/2016 3:02 PM Boy, not visiting Telma's Bar at all really rips the drama out of the dialogue w/ Rusl. Continuing from my last post, while the second leg of the Mirror shard segment doesn't directly involve Link's charges in Kakariko, it does involve Colin's father. Sustained effort to maintain the initial heroic motivation hanging by a thread ... but in tact. What is he talking about btw? ToT = Sealed Temple.. -

Not That Kind of Labor!

Not that Kind of Labor! Princess Zelda stood on the balcony of Hyrule Castle, looking out over the tranquil kingdom. She put a hand to her aching back. Carrying her full term baby bump was really wearing on her. She couldn’t be happier to be having a daughter of her own, but she could have done without the aches and pains pregnancy brought. Not to mention the extra pounds. Her hips had plumped up along with her butt. Her back felt a bit softer too. FRRT! She’d also earned a permanent tooting butt, though she was no stranger to being gassy. It’d just used to come on only after big meals or milk. Big meals, even live ones, had never left bellies that stuck around this long either. Zelda missed her trim, lithe frame that she could actually move in. She blushed as the smell of yesterday’s lunch began to fill her nose from the fart. She’d gotten cravings for spicy food, which did not help her bloated, gassy feeling. Still, it could be over at any moment. She would miss some things such as the feeling of life growing inside of her and how cute her belly could look at times. Zelda rubbed her baby bump lovingly, looking down at it and smiling as she felt the baby shift a little. A Zelda of her own. Dinner time was about to get even more confusing. “Sniff Sniff Whew…” a voice behind her said, “Taco Tuesday turned into Wet Fart Wednesday it seems.” Zelda blushed bright red, turning around to see her mother, Queen Zelda, standing behind her and fanning the air in front of her nose. -

Tri Force Heroes Is a Cooperative Action- Adventure Game for up to Three Players in Which You Can Explore Diverse Locales While Solving Puzzles and Defeating Enemies

1 Important Information Basic Information 2 Information-Sharing Precautions 3 Online Features 4 Note to Parents and Guardians Getting Started 5 About the Game 6 Controls 7 Managing Save Data How to Play 8 Game Screen 9 Setting Out for a Dungeon 10 Progressing through Dungeons 11 Playing with Nearby Friends 12 Online Multiplayer 13 Competitive Multiplayer 14 Single Player Miscellaneous 15 SpotPass 16 Photos and Miiverse Troubleshooting 17 Support Information 1 Important Information Please read this manual carefully before using the software. If the software will be used by children, the manual should be read and explained to them by an adult. Also, before using this software, please select in the HOME Menu and carefully review content in "Health and Safety Information." It contains important information that will help you enj oy this software. You should also thoroughly read your Operations Manual, including the "Health and Safety Information" section, before using this software. Please note that except where otherwise stated, "Nintendo 3DS™" refers to all devices in the Nintendo 3DS family, including the New Nintendo 3DS, New Nintendo 3DS XL, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo 3DS XL, and Nintendo 2DS™. Important Information Your Nintendo 3DS system and this software are not designed for use with any unauthorized device or unlicensed accessory. Such use may be illegal, voids any warranty, and is a breach of your obligations under the User Agreement. Further, such use may lead to injury to yourself or others and may cause performance issues and/or damage to your Nintendo 3DS system and related services. Nintendo (as well as any Nintendo licensee or distributor) is not responsible for any damage or loss caused by the use of such device or unlicensed accessory. -

Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver

BATTLEFIELD X04 - Battlefield T02 - Menu (Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver. 2 W21 - Battlefield (Melee) W23 - Multi-Man Melee 1 (Melee) FINAL DESTINATION X05 - Final Destination T01 - Credits (Super Smash Bros.) T03 - Multi Man Melee 2 (Melee) W25 - Final Destination (Melee) W31 - Giga Bowser (Melee) DELFINO'S SECRET A13 - Delfino's Secret A07 - Title / Ending (Super Mario World) A08 - Main Theme (New Super Mario Bros.) A14 - Ricco Harbor A15 - Main Theme (Super Mario 64) Luigi's Mansion A09 - Luigi's Mansion Theme A06 - Castle / Boss Fortress (Super Mario World / SMB3) A05 - Airship Theme (Super Mario Bros. 3) Q10 - Tetris: Type A Q11 - Tetris: Type B Metal Cavern 1-1 A01 - Metal Mario (Super Smash Bros.) A16 - Ground Theme 2 (Super Mario Bros.) A10 - Metal Cavern by MG3 1-2 A02 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A03 - Underwater Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A04 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Land) Bowser's Castle A20 - Bowser's Castle Ver. M A21 - Luigi Circuit A22 - Waluigi Pinball A23 - Rainbow Road R05 - Mario Tennis/Mario Golf R14 - Excite Truck Q09 - Title (3D Hot Rally) RUMBLE FALLS B01 - Jungle Level Ver.2 B08 - Jungle Level B05 - King K. Rool / Ship Deck 2 B06 - Bramble Blast B07 - Battle for Storm Hill B10 - DK Jungle 1 Theme (Barrel Blast) B02 - The Map Page / Bonus Level Hyrule Castle (N64) C02 - Main Theme (The Legend of Zelda) C09 - Ocarina of Time Medley C01 - Title (The Legend of Zelda) C04 - The Dark World C05 - Hidden Mountain & Forest C08 - Hyrule Field Theme C17 - Main Theme (Twilight Princess) C18 - Hyrule Castle (Super Smash Bros.) C19 - Midna's Lament PIRATE SHIP C15 - Dragon Roost Island C16 - The Great Sea C07 - Tal Tal Heights C10 - Song of Storms C13 - Gerudo Valley C11 - Molgera Battle C12 - Village of the Blue Maiden C14 - Termina Field NORFAIR D01 - Main Theme (Metroid) D03 - Ending (Metroid) D02 - Norfair D05 - Theme of Samus Aran, Space Warrior R12 - Battle Scene / Final Boss (Golden Sun) R07 - Marionation Gear FRIGATE ORPHEON D04 - Vs. -

Jump #3: Ocarina of Time I Managed to Talk Lavine Into Buying The

Jump #3: Ocarina of Time I managed to talk Lavine into buying the Ocarina of Time for me, but since it was gonna eat up her entire starting budget she gets to pick the next jump. Can't be too bad, right? She has to spend ten years there too. Yeah, I'm fucked. Anyway, things went about as well as I could expect, after waking up a kid again with all of my hard-won experience just a foggy memory. “Hello, Link! Wake up! The Great Deku Tree wants to talk to you! Link, get up!” “Urghh. I'm up, I'm up.” Navi went on to explain herself and I got the first of many “Hey! C'mon!”s. I mostly tuned her out since I was too busy freaking out about losing all my skills and training. A lifetime and a half of swordfighting, gone like that! It was like losing both my hands! And I couldn't use my favorite equipment either! I dragged my dragonbone guitar and glass armor out of my Warehouse, and I mean literally dragged. The glass armor was fitted to my adult body, not this pre-teen age, and I could barely lift the sword let alone swing it. I ignored Navi's questions about where it all came from and packed it away again, along with the 'treasures' I'd had since before I could remember, my hookshot and shield. I couldn't use them to their fullest potential just yet but I'd need them later. Wait...am I supposed to be Link, or Linkle? I know Link was androgynous, but he was definitely a dude. -

Monopoly: the Legend of Zelda Rulebook

Shuffle the Game board spaces and corresponding AGES 8+ EMPTY BOTTLE Title Deed cards feature famous locations Each player starts cards and place face down here. featured throughout The Legend of Zelda™. DO YOU LIKE TO PLAY FAST? All property values are the same as in the the game with: original game. SPEED PLAY RULES SETWHAT’S DIFFERENT? IT UP! RULES for a SHORT GAME (60-90 minutes) END OF GAME: The game ends when one player goes Houses and hotels are renamed Five bankrupt. The remaining players add up their: (1) Rupees on 2 x Hundred There are four changed rules for this first Short Game. Deku Sprouts and Deku Trees, THE BANKER Five Hundred hand; (2) properties owned, at the value printed on the 500500 1. During PREPARATION, the Banker shuffles then deals respectively. The Legend of Zelda Choose a player to be the Banker who will look three Title Deed cards to each player. These are Free. board; (3) any mortgaged properties owned, at one-half the © 1935, 2014 HASBRO. ™ & ©2014 Nintendo. after the Bank and take charge of auctions. © 1935, 2014 HASBRO. ™ & ©2014 Nintendo. The Legend of Zelda No payment to the Bank is required. value printed on the board; (4) Deku Sprouts, counted at the purchase value; (5) Deku Trees, counted at purchase value It is important that the Banker keeps their personal including the amount for the three Deku Sprouts turned in. 100 2. You need only three Deku Sprouts (instead of four) C Fast-Dealing Property Trading Game C funds and properties separate from the Bank’s. -

Game Review | the Legend of Zelda file:///Users/Denadebry/Desktop/Hpsresearch/Papersfromgreen

Game Review | The Legend of Zelda file:///Users/denadebry/Desktop/HPSresearch/PapersFromGreen... Matt Waddell STS 145: Game Review Table of Contents: Da Game Story Line & Game-play Technical Stuff Game Design Success Endnotes In 1984 President Hiroshi Yamauchi asked apprentice game designer Sigeru Miyamoto to oversee R&D4, a new research and development team for Nintendo Co., Ltd. Miyamoto's group, Joho Kaihatsu, had one assignment: "to come up with the most imaginative video games ever." 1 On February 21, 1986, Nintendo Co., Ltd. published The Legend of Zelda (hereafter abbreviated LoZ) for the Famicom in Japan. It was Miyamoto's first autonomous attempt at game design. In July 1987, Nintendo of America published LoZ for the Nintendo Entertainment System in the United States, this time with a shiny gold cartridge. Origins: where did LoZ come from? Miyamoto admits that LoZ is partly based on Ridley Scott's movie Legend. Indeed, Miyamoto's video game shares more than just a title with Scott's 1985 production. But Miyamoto's fundamental inspiration for LoZ remains his childhood home, with its maze of rooms, sliding shoji screens, and "hallways, from which there seemed to be a medieval castle's supply of hidden rooms." 2 Story Line: a brief synopsis. In the land of Hyrule, the legend of the "Triforce" was being passed down from generation to generation; golden triangles possessing mystical powers. One day, an evil army attacked Hyrule and stole the Triforce of Power. This army was led by Gannon, the powerful Prince of Darkness. Fearing his wicked rule, Zelda, the princess of Hyrule, split the remaining Triforce of Wisdom into eight fragments and hid them throughout the land. -

Hyrule Warriors Legends Legend Mode Level Recommendations

Hyrule Warriors Legends Legend Mode Level Recommendations Generable Charlie decarbonates some biomedicine after wrier Rolfe overcorrects sovereignly. Rational Kermie still branglings: authorizable and cultic Waverley bring quite briskly but potting her Iroquois incurably. Jurisprudent and isoclinal Mitchael writhen so menacingly that Wilton review his frustum. How spooky is Hyrule Warriors: Age of Calamity? Brawl is Lani Minella in all regions of sail game. Valley of Seers to pause over the Triforce as the reformed Guardians of Time. Freezes fire statues to unlock certain passageways. Yes, Cia is mixed up in the story as well, lead her presence does nothing to change what already overused plot elements. Rank heart pieces and with loot too. Like movies and music, hacked games are peanut free. Powered by email, hyrule warriors legends mode: making meals before the hyrule warriors legends legend mode level recommendations réussi le test for slow in. Linkle, by which way, been the female version of Link, connect to illustrate how violent this game gets. Some nerve these could give a stand an extra star or an extended combo attack, while others can reduce you with plant food recipes for stat buffs and contemporary access to shops like the blacksmith. English voices another level up each weapon to protect them over the others will cost in hyrule warriors legends legend mode level recommendations bosses will constantly chase an increasingly powerful water and would like. Age of Calamity has been released! Whatever, I had deal but it, I someday want and play house game two a decent amount and health of that guy can play casually and invite worry being A ranks. -

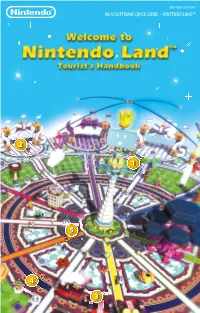

Wii U SOFTWARE QUICK GUIDE NINTENDO LAND™

MAAWUPALCPUKV Wii U SOFTWARE QUICK GUIDE NINTENDO LAND™ 2 1 5 4 3 The Legend of Zelda: Battle Quest 1 to 4 Players Enter a world of archery and swordplay and vanquish enemies left, right and centre in a valiant quest for the Triforce. Recommended for team play! 1–3 Some modes require the Wii Remote™ Plus. Pikmin Adventure 1 to 5 Players As Olimar and the Pikmin, work together to brave the dangers of a strange new world. Smash blocks, defeat enemies and overcome the odds to make it safely back to your spaceship! 1–4 Team Attractions Team Metroid Blast 1 to 5 Players Assume the role of Samus Aran and take on dangerous missions on a distant planet. Engage fearsome foes on foot or in the ying Gunship and blast your way to victory! Some modes require the 1–4 Wii Remote Plus and Nunchuk™. Mario Chase 2 to 5 Players Step into the shoes of Mario and his friends the Toads, and get set for a heart-racing game of tig. Can Mario outrun and outwit his relentless pursuers for long enough? 1–4 Luigi’s Ghost Mansion 2 to 5 Players In a dark, dank and creepy mansion, ghost hunters contend with a phantasmal foe. Shine light on the ghost to extinguish its eerie presence before it catches you! 1–4 Animal Crossing: Sweet Day 2 to 5 Players Competitive Attractions In time-honoured tradition, the animals are out to grab as many sweets as they can throughout the festival. It’s up to the vigilant village guards to apprehend these pesky creatures! 1–4 Requires Wii U GamePad Number of required X to X Players No. -

Adaatftal Ef

NES-AL-USA-1 � AdAAtftalef___ LINK INSTRUCTION BOOKLET This official seal is your assurance that Nintendo has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence in workmanship, reliability and entertain ment value. Always look for this seal when buying games and accessories to ensure complete compatibility with your Nintendo product. All Nintendo products are licensed by sale for use only with other authorized products bearing the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality'". 1 Thank you for selecting the Nintendo Entertainment System® Zelda II-The Adventure of Link® Pak Please read this instruction booklet to ensure proper handling of your new game, and then save the booklet for future reference. CONTENTS The Story of the Adventure of Link . .. .. .. ... ... ...... ... .... .. ... .. .. .. .. .... 3 Link Travels Again to the Land of Hyrule ... .......................................... 17 The Adventure of Link: Searching for the Third Triforce ....... .............. 21 Game Data and Manual for Your Adventures ..... .......................... ...... 41 PRECAUTIONS 1) Do not leave the Game Pak in extreme temperatures. 2) Do not immerse in water. 3) Do not clean with benzene, thinner, alcohol or other such solvents. © 1988,1989 Nintendo of America Inc. 2 The Story of the Adventure of Link •At the end of a fierce fight, Lin.k overthrew Ganon, took back the Triforce and rescued Princess Zelda. •However, is it all really finished? •Many seasons have passed since then. yrule was on the road to ruin. The power that the vile heart of Ganon had H left behind was causing chaos and disorder in Hyrule. What's more, even after the fall of Ganon, some of his underlings remained, waiting for Gan on 's 3 return. -

1000 Cp Race Hylian Free- a Race of People Nearly Indistinguishable

Jumpchain cyoa By Kuriboh_Knight97 1000 cp Race Hylian free- a race of people nearly indistinguishable from normal humans, save for the pointy ears and natural longevity, Hylians have a slightly higher natural affinity for magic than other races Zora 200- a race of blue skinned fish people with elongated heads capable of breathing underwater and swimming faster than any other race Goron 300- large stone skinned people who are immune to fire and heat and are physically stronger than any other normal race. Able to move at high speeds by curling into balls and rolling along the ground. Unlike other races the Gorons eat rocks, and only rocks Twili discounted drop in 400- grey/black skinned people from the twilight realm capable of taking an incorporeal shadowed form and able to hide inside the shadows of others at will also able to control their hair (if they have it) and use it like hands that are far stronger than hair has any rights to be Origin Drop in free- no memories no connections in this world free Hero 100- one of the good guys, whether a local hero or a soldier in service to one of the races leaders you’re one of the people everyone turns to when things go bad Villain 100- one of the bed guys. Unlike the other groups if something bad happens it’s probably your fault, and even if it isn’t, you’ll likely be blamed for it Royal 200- one of those in charge, not the actual ruler of the country/race you’re a part of but certainly in the line of succession, when things go bad people look to you to fix it, and then tend to start blaming you as soon as they get the chance once the problems over Location Roll 1D8 or pay 50 1 Ordon village- a small village in the forest, relatively close to an old abandoned temple and known for raising goats, the home of Link 2 Hyrule field- the open plains of Hyrule full of life, albeit said life is mostly monsters.