The Expansion of Gender Roles in the Legend of Zelda Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero's Experience in the Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt in Fulfillment Of

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt In fulfillment of M.M. in Music Theory Supervised by Dr. Benjamin Graf, Dr Graham Hunt, and Micah Hayes May 2019 The University of Texas at Arlington ii ABSTRACT Jillian Wyatt: The Journey of a Hero Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Under the supervision of Dr. Graham Hunt The research in this study explores concepts in the music from select games in The Legend of Zelda franchise. The paper utilizes topic theory and Schenkerian analysis to form connections between concepts such as adventure in the overworld, the fight or flight response in an enemy encounter, lament at the loss of a companion, and heroism by overcoming evil. This thesis identifies and discusses how Koji Kondo’s compositions evoke these concepts, and briefly questions the reasoning. The musical excerpts consist of (but are not limited to): The Great Sea (Windwaker; adventure), Ganondorf Battle (Ocarina of Time; fight or flight), Midna’s Lament (Twilight Princess; lament), and Hyrule Field (Twilight Princess; heroism). The article aims to encourage readers to explore music of different genres and acknowledge that conventional analysis tools prove useful to video game music. Additionally, the results in this study find patterns in Koji Kondo’s work such as (to identify a select few) modal mixture, military topic, and lament bass to perpetuate an in-game concept. The most significant aspect of this study suggests that the music in The Legend of Zelda reflects in-game ideas and pushes a musical concept to correspond with what happens on screen while in gameplay. -

Tri Force Heroes Is a Cooperative Action- Adventure Game for up to Three Players in Which You Can Explore Diverse Locales While Solving Puzzles and Defeating Enemies

1 Important Information Basic Information 2 Information-Sharing Precautions 3 Online Features 4 Note to Parents and Guardians Getting Started 5 About the Game 6 Controls 7 Managing Save Data How to Play 8 Game Screen 9 Setting Out for a Dungeon 10 Progressing through Dungeons 11 Playing with Nearby Friends 12 Online Multiplayer 13 Competitive Multiplayer 14 Single Player Miscellaneous 15 SpotPass 16 Photos and Miiverse Troubleshooting 17 Support Information 1 Important Information Please read this manual carefully before using the software. If the software will be used by children, the manual should be read and explained to them by an adult. Also, before using this software, please select in the HOME Menu and carefully review content in "Health and Safety Information." It contains important information that will help you enj oy this software. You should also thoroughly read your Operations Manual, including the "Health and Safety Information" section, before using this software. Please note that except where otherwise stated, "Nintendo 3DS™" refers to all devices in the Nintendo 3DS family, including the New Nintendo 3DS, New Nintendo 3DS XL, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo 3DS XL, and Nintendo 2DS™. Important Information Your Nintendo 3DS system and this software are not designed for use with any unauthorized device or unlicensed accessory. Such use may be illegal, voids any warranty, and is a breach of your obligations under the User Agreement. Further, such use may lead to injury to yourself or others and may cause performance issues and/or damage to your Nintendo 3DS system and related services. Nintendo (as well as any Nintendo licensee or distributor) is not responsible for any damage or loss caused by the use of such device or unlicensed accessory. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games

The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Katharine Phelps Humanities 497W December 15, 2007 Just remember that my being a woman doesn't make me any less important! --Faris Final Fantasy V 1 The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Female characters, even as a token love interest, have been a mainstay in adventure games ever since Nintendo became a household name. One of the oldest and most famous is the princess of the Super Mario games, whose only role is to be kidnapped and rescued again and again, ad infinitum. Such a character is hardly emblematic of feminism and female empowerment. Yet much has changed in video games since the early 1980s, when Mario was born. Have female characters, too, changed fundamentally? How much has feminism and changing ideas of women in Japan and the US impacted their portrayal in console games? To address these questions, I will discuss three popular female characters in Nintendo adventure game series. By examining the changes in portrayal of these characters through time and new incarnations, I hope to find a kind of evolution of treatment of women and their gender roles. With such a small sample of games, this study cannot be considered definitive of adventure gaming as a whole. But by selecting several long-lasting, iconic female figures, it becomes possible to show a pertinent and specific example of how some of the ideas of women in this medium have changed over time. A premise of this paper is the idea that focusing on characters that are all created within one company can show a clearer line of evolution in the portrayal of the characters, as each heroine had her starting point in the same basic place—within Nintendo. -

Fall 2014 Concert Series

Fall 2014 ConCert SerieS NIGEL HORNE, MUSIC DIRECTOR LAURA STAYMAN, CONCERT LEADER Saturday, December 13 - Herndon, VA Saturday, December 20 - Rockville, MD [Classical Music. Play On!] WMGSO.org | @WMGSO | fb/MetroGSO about the WMGSo The WMGSO is a community orchestra and choir whose mis- sion is to share and celebrate video game music with as wide an audience as possible, primarily by putting on affordable, accessi- ble concerts in the area. Game music weaves a complex, melodic thread through the traditions, values, and mythos of an entire culture, and yet it largely escapes recognition in professional circles. Game music has powerful meaning to millions of people. In it, we find deep emotion and basic truths about life. We find ourselves — and we find new ways of thinking about and expressing ourselves. We find meaning that transcends the medium itself and stays with us for life. WMGSO showcases this emerging genre and highlights its artistry. Incorporated in December 2012, WMGSO grew from the spirit of the GSO at the University of Maryland. About a dozen members showed up at WMGSO’s inaugural rehearsal. Since then, the group has grown to more than 60 musicians. The WMGSO’s debut at Rockville High School in June attracted an audience of more than 500. Also in June, the IRS accepted WMGSO’s appli- cation to become a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization, opening even more opportunities for the orchestra to grow. adMiniStration Music Director, Nigel Horne Chorusmaster, Jacob Coppage-Gross President, Ayla Hurley Vice President, Joseph Wang Secretary, Laura Stayman Treasurer, Chris Apple Public Relations, Robert Garner Webmaster, Jason Troiano Event Coordinator, Diana Taylor Assistant Treasurer, Patricia Lucast supporters From securing rehearsal space and equipment rentals, to print- ing concert programs and obtaining music licenses, we rely on the support of our members and donors. -

Jump #3: Ocarina of Time I Managed to Talk Lavine Into Buying The

Jump #3: Ocarina of Time I managed to talk Lavine into buying the Ocarina of Time for me, but since it was gonna eat up her entire starting budget she gets to pick the next jump. Can't be too bad, right? She has to spend ten years there too. Yeah, I'm fucked. Anyway, things went about as well as I could expect, after waking up a kid again with all of my hard-won experience just a foggy memory. “Hello, Link! Wake up! The Great Deku Tree wants to talk to you! Link, get up!” “Urghh. I'm up, I'm up.” Navi went on to explain herself and I got the first of many “Hey! C'mon!”s. I mostly tuned her out since I was too busy freaking out about losing all my skills and training. A lifetime and a half of swordfighting, gone like that! It was like losing both my hands! And I couldn't use my favorite equipment either! I dragged my dragonbone guitar and glass armor out of my Warehouse, and I mean literally dragged. The glass armor was fitted to my adult body, not this pre-teen age, and I could barely lift the sword let alone swing it. I ignored Navi's questions about where it all came from and packed it away again, along with the 'treasures' I'd had since before I could remember, my hookshot and shield. I couldn't use them to their fullest potential just yet but I'd need them later. Wait...am I supposed to be Link, or Linkle? I know Link was androgynous, but he was definitely a dude. -

Monopoly: the Legend of Zelda Rulebook

Shuffle the Game board spaces and corresponding AGES 8+ EMPTY BOTTLE Title Deed cards feature famous locations Each player starts cards and place face down here. featured throughout The Legend of Zelda™. DO YOU LIKE TO PLAY FAST? All property values are the same as in the the game with: original game. SPEED PLAY RULES SETWHAT’S DIFFERENT? IT UP! RULES for a SHORT GAME (60-90 minutes) END OF GAME: The game ends when one player goes Houses and hotels are renamed Five bankrupt. The remaining players add up their: (1) Rupees on 2 x Hundred There are four changed rules for this first Short Game. Deku Sprouts and Deku Trees, THE BANKER Five Hundred hand; (2) properties owned, at the value printed on the 500500 1. During PREPARATION, the Banker shuffles then deals respectively. The Legend of Zelda Choose a player to be the Banker who will look three Title Deed cards to each player. These are Free. board; (3) any mortgaged properties owned, at one-half the © 1935, 2014 HASBRO. ™ & ©2014 Nintendo. after the Bank and take charge of auctions. © 1935, 2014 HASBRO. ™ & ©2014 Nintendo. The Legend of Zelda No payment to the Bank is required. value printed on the board; (4) Deku Sprouts, counted at the purchase value; (5) Deku Trees, counted at purchase value It is important that the Banker keeps their personal including the amount for the three Deku Sprouts turned in. 100 2. You need only three Deku Sprouts (instead of four) C Fast-Dealing Property Trading Game C funds and properties separate from the Bank’s. -

Game Review | the Legend of Zelda file:///Users/Denadebry/Desktop/Hpsresearch/Papersfromgreen

Game Review | The Legend of Zelda file:///Users/denadebry/Desktop/HPSresearch/PapersFromGreen... Matt Waddell STS 145: Game Review Table of Contents: Da Game Story Line & Game-play Technical Stuff Game Design Success Endnotes In 1984 President Hiroshi Yamauchi asked apprentice game designer Sigeru Miyamoto to oversee R&D4, a new research and development team for Nintendo Co., Ltd. Miyamoto's group, Joho Kaihatsu, had one assignment: "to come up with the most imaginative video games ever." 1 On February 21, 1986, Nintendo Co., Ltd. published The Legend of Zelda (hereafter abbreviated LoZ) for the Famicom in Japan. It was Miyamoto's first autonomous attempt at game design. In July 1987, Nintendo of America published LoZ for the Nintendo Entertainment System in the United States, this time with a shiny gold cartridge. Origins: where did LoZ come from? Miyamoto admits that LoZ is partly based on Ridley Scott's movie Legend. Indeed, Miyamoto's video game shares more than just a title with Scott's 1985 production. But Miyamoto's fundamental inspiration for LoZ remains his childhood home, with its maze of rooms, sliding shoji screens, and "hallways, from which there seemed to be a medieval castle's supply of hidden rooms." 2 Story Line: a brief synopsis. In the land of Hyrule, the legend of the "Triforce" was being passed down from generation to generation; golden triangles possessing mystical powers. One day, an evil army attacked Hyrule and stole the Triforce of Power. This army was led by Gannon, the powerful Prince of Darkness. Fearing his wicked rule, Zelda, the princess of Hyrule, split the remaining Triforce of Wisdom into eight fragments and hid them throughout the land. -

Video Gaming and Death

Untitled. Photographer: Pawel Kadysz (https://stocksnap.io/photo/OZ4IBMDS8E). Special Issue Video Gaming and Death edited by John W. Borchert Issue 09 (2018) articles Introduction to a Special Issue on Video Gaming and Death by John W. Borchert, 1 Death Narratives: A Typology of Narratological Embeddings of Player's Death in Digital Games by Frank G. Bosman, 12 No Sympathy for Devils: What Christian Video Games Can Teach Us About Violence in Family-Friendly Entertainment by Vincent Gonzalez, 53 Perilous and Peril-Less Gaming: Representations of Death with Nintendo’s Wolf Link Amiibo by Rex Barnes, 107 “You Shouldn’t Have Done That”: “Ben Drowned” and the Uncanny Horror of the Haunted Cartridge by John Sanders, 135 Win to Exit: Perma-Death and Resurrection in Sword Art Online and Log Horizon by David McConeghy, 170 Death, Fabulation, and Virtual Reality Gaming by Jordan Brady Loewen, 202 The Self Across the Gap of Death: Some Christian Constructions of Continued Identity from Athenagoras to Ratzinger and Their Relevance to Digital Reconstitutions by Joshua Wise, 222 reviews Graveyard Keeper. A Review by Kathrin Trattner, 250 interviews Interview with Dr. Beverley Foulks McGuire on Video-Gaming, Buddhism, and Death by John W. Borchert, 259 reports Dying in the Game: A Perceptive of Life, Death and Rebirth Through World of Warcraft by Wanda Gregory, 265 Perilous and Peril-Less Gaming: Representations of Death with Nintendo’s Wolf Link Amiibo Rex Barnes Abstract This article examines the motif of death in popular electronic games and its imaginative applications when employing the Wolf Link Amiibo in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). -

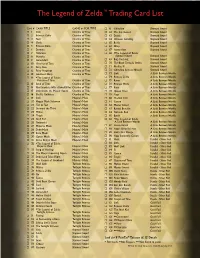

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List Card # CARD TITLE GAME or FOIL TYPE ¨ 61 Ghirahim Skyward Sword ¨ 1 Link Ocarina of Time ¨ 62 The Imprisoned Skyward Sword ¨ 2 Princess Zelda Ocarina of Time ¨ 63 Demise Skyward Sword ¨ 3 Navi Ocarina of Time ¨ 64 Crimson Loftwing Skyward Sword ¨ 4 Sheik Ocarina of Time ¨ 65 Beetle Skyward Sword ¨ 5 Princess Ruto Ocarina of Time ¨ 66 Whip Skyward Sword ¨ 6 Darunia Ocarina of Time ¨ 67 Scattershot Skyward Sword ¨ 7 Twinrova Ocarina of Time ¨ 68 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 8 Morpha Ocarina of Time Skyward Sword Skyward Sword ¨ 9 Ganondorf Ocarina of Time ¨ 69 Bug Catching Skyward Sword ¨ 10 Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 70 The Black Tornado Strikes Skyward Sword ¨ 1 1 Fairy Bow Ocarina of Time ¨ 7 1 Finding Fi Skyward Sword ¨ 12 Fairy Slingshot Ocarina of Time ¨ 72 Ghirahim Reveals Himself Skyward Sword ¨ 13 Goddess’s Harp Ocarina of Time ¨ 73 Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 14 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 74 Princess Zelda A Link Between Worlds Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 75 Ravio A Link Between Worlds ¨ 15 Song of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 76 Princess Hilda A Link Between Worlds ¨ 16 First Encounter With a Powerful Foe Ocarina of Time ¨ 77 Irene A Link Between Worlds ¨ 17 Link Draws the Master Sword Ocarina of Time ¨ 78 Queen Oren A Link Between Worlds ¨ 18 Sheik’s Guidance Ocarina of Time ¨ 79 Yuga A Link Between Worlds ¨ 19 Link Majora’s Mask ¨ 80 Shadow Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 20 Happy Mask Salesman Majora’s Mask ¨ 8 1 Ganon A Link Between Worlds ¨ 2 1 Tatl & Tael Majora’s Mask ¨ 82 Master Sword -

Wind Waker Manual

OFFICIAL NINTENDO POWER PLAYER'S GUIDE AVAILABLE AT YOUR NEAREST RETAILER! WWW.NINTENDO.COM Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.A. www.nintendo.com IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET 50520A IN S T R U C T IO N B O O K LET PRINTED IN USA W A R N IN G : P L E A S E C A R E FU L L Y R E A D T HE S E P A R A T E P R E C A U T IO N S B O O K L E T IN C L U D E D W IT H T HIS P R O D U C T WARNING - Electric Shock B E FO R E U S IN G Y O U R N IN T E N D O ® HA R D W A R E S Y S T E M , To avoid electric shock when you use this system: G A M E D IS C O R A C C E S S O R Y . T HIS B O O K L E T C O N T A IN S IM P O R T A N T S A FE T Y IN FO R M A T IO N . Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires.