Romantic Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Cannot Tell You More of This Arcadia Than That It Is at Present

This concert marked the the conclusion of our yearly Master class which offers to talented young musicians a week’s course performing on historic keyboard instruments in Tuscany, under the expert guidance of Professor Ella Sevskaya. The Master class began as a collaboration with the P. I. Tchaikovsky State Conservatory of Moscow, to facilitate the studies of Russian students who rarely have the opportunity of playing on historic instruments in their own country. In recent years we have extended the Masterclass to participants from other countries; this year we have one student from Japan, as well as five from Russia, who all have their origins in the Department of Historical and Contemporary Performance of the Moscow State Conservatory. Anastasia Akinfina, Sophia Gandilyan, Sergei Lukaschuk and Yulia Uspenskaya come to us directly from the Department, while Alexandra Nepomnyashchaya is a graduate ; she subsequently acquired a Master in harpsichord and in fortepiano at the Conservatory of Amsterdam, and is now undertaking a specialization in early keyboard at the Hochschule für Musik, Munich. Hanano Muratsubaki begins her study at the Music Department of the University of Augsburg this fall. The participants of our Masterclass worked this week in the Laboratorio di Restauro del Fortepiano of Florence, which kindly made available the fine fortepiano made in Vienna by Johann Schantz ca.1810-1815 which we hear in this evening’s recital. We are also grateful to the Accademia Bartolomeo Cristofori: amici del fortepiano, which kindly gave us access to their extraordinary collection of historic instruments. Ella Sevskaya was born in the Ukraine in 1961. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Bavouzet Plays Sonatas by CLEMENTI DUSSEK HUMMEL WÖLFL

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet plays Sonatas by CLEMENTI DUSSEK HUMMEL WÖLFL Muzio Clementi Muzio Engraving by H. Cook after portrait by James Lonsdale (1777 – 1839) / AKG Images / Universal Images Group / Universal History Archive Joseph Wölfl (1773 – 1812) Sonata, Op. 33 No. 3 (1805) 14:56 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur 1 Allegro 8:04 2 Andante. Cantabile 2:29 3 Rondo. Allegretto – Minore – Maggiore 4:24 Muzio Clementi (1752 – 1832) Sonata, Op. 50 No. 1 (1804 – 21) 21:50 in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur Dedicated to Luigi Cherubini 4 Allegro maestoso e con sentimento 8:34 5 Adagio sostenuto e patetico – Andante con moto. Canone – Adagio. Tempo I – 5:28 6 Allegro vivace 7:47 3 Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778 – 1837) Sonata No. 3, Op. 20 (c. 1807) 21:02 in F minor • in f-Moll • en fa mineur Magdalene von Kurzbeck gewidmet 7 Allegro moderato – Adagio – Allegro agitato 9:23 8 Adagio maestoso – 7:02 9 Finale. Presto – Ancor più presto 4:35 Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760 – 1812) Sonata, Op. 61, C 211 ‘Élégie harmonique sur la mort de son Altesse Royale le prince Louis-Ferdinand de Prusse’ (1806 – 07) 16:55 in F sharp minor • in fis-Moll • en fa dièse mineur Dédiée à Son Altesse le Prince de Lobkowitz, duc de Raudnitz 10 Lento patetico – Tempo agitato 11:34 11 Tempo vivace e con fuoco quasi presto 5:20 4 12 Musical illustrations 7:49 Illustration 1 Clementi: Movement 1 (chromatic scales) Hummel: Movement 1 (chromatic scales) Dussek: Movement 1 (chromatic scales) Illustration 2 Hummel: Adagio Beethoven: Sonata, Op. -

John Field's Piano Concerto No. 1.Pdf (6.285Mb)

JOHN FIELD’S PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Mary Ermel Walker In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Major Department: Music September 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title John Field’s Piano Concerto No. 1 By Mary Ermel Walker The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Andrew Froelich Chair Robert Groves Virginia Sublett John Helgeland Approved: 11/16/15 John Miller Date Department Chair ABSTRACT While there are recordings of all seven of John Field’s piano concertos, there are no two- piano versions published that include the transcribed orchestra in the second piano part, with the exception of the second concerto. This paper reviews the life and music of John Field with particular attention on his first concerto and on the creation of an orchestral reduction for performance on two pianos. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my professors at North Dakota State University for their patience and support throughout my coursework and the writing of this paper, especially Dr. Andrew Froelich for his invaluable input on the orchestra reduction, Dr. Robert Groves for his help with the composition of this paper, and Dr. Virginia Sublett for her support and encouragement along the way. The orchestra reduction is based on a publication provided courtesy of the Edwin A Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music at the Free Library of Philadelphia. -

In the Footsteps of Jan Ladislav Dussek: an Interview by Paul Archambault

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 1 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Winter 1979-1980 Article 6 1979 In the Footsteps of Jan Ladislav Dussek: An Interview by Paul Archambault Frederick Marvin Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Recommended Citation Marvin, Frederick (1979) "In the Footsteps of Jan Ladislav Dussek: An Interview by Paul Archambault," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marvin: In the Footsteps of Jan Ladislav Dussek: An Interview by Paul Arc In the FootsteQS of Jan Ladislav Dussek An Interview by Paul Archambault Frederick Marvin PAUL ARCHAMBAULT: Professor Marvin, as an internationally known concert pianist, professor of piano, and artist-in-resi dence at Syracuse University, you have recently become inter ested in a relatively obscure eighteenth-century Czech composer named Jan Ladislav Dussek. How- and why- did this come about? FREDERICK MARVIN: I first became interested in Dussek when I browsed through a music shop in Prague a number of years ago and found a Czech edition of his piano sonatas that at first glance looked rather unusual. Then three years ago my recording com pany, Genesis, which releases a great deal of romantic music, asked me if I knew about Dussek and if I would be interested in recording all twenty-nine of his sonatas. -

All-Dussek Program to Commemorate the 200Th Anniversary Tion Lamentations and Praises

Ms. Janssen began her cello and piano studies at the age of seven at the Kharkov Spe- cial Music Boarding School in Ukraine, and later in the Preparatory Department of the Longy School of Music, where she was a principal cellist of the Young Performers Chamber Orchestra. Over the years, Ms. Janssen has studied cello under professors I. D. Rojavsky, L. S. Nikulina, Terry King, Thomas Kraines, Mihail Jojatu, and Marc Johnson, and piano under L.A. Podpalnaya, Philis Asseta, and Lyubov Shlain. Ms. Janssen has taken part in master classes with cellists Laurence Lesser, John Kaboff, Natasha Brofsky, Andrew Pearce, Kangho Lee, Joshua Gordon, and Natalia Gutman. She holds an Undergraduate Diploma with Distinction in Cello Performance F ACULTY ARTIST RecITAL from Longy School of Music, a Bachelors of Music degree from Emerson College, and a Master of Music degree with Honor Award for outstanding achievement in String Performance from Boston University. Erik Entwistle, piano Clayton Hoener, violin Meghan Jacoby, flute Daria Janssen, cello Sunday, March 4, 2012, 7 P.M. Longy School of Music Edward M. Pickman Concert Hall 27 Garden Street, Cambridge ZABRISKIE HOUSE 27 GARDEN STREET, CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 617.876.0956 X1500 | www.longy.edu All-Dussek program to commemorate the 200th anniversary tion Lamentations and Praises. of the composer’s death Mr. Hoener was a founding member and first violinist of the Boston Composers String Quartet, winning a silver medal in the 1993 Osaka Chamber Music Competition, a Sonata in B-flat major, Op. 69, No. 1 Jan Ladislav Dussek Chamber Music America Three-Year Residency Grant, and the 1995 CMA/ASCAP Allegro molto con fuoco (1760–1812) Award for Adventurous Programming. -

Piano Sonatas of Beethoven and Dussek

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 Aspects of Form, Tonality, and Texture in the ''Farewell'' Piano Sonatas of Beethoven and Dussek Kyoung Cha West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cha, Kyoung, "Aspects of Form, Tonality, and Texture in the ''Farewell'' Piano Sonatas of Beethoven and Dussek" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 438. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/438 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aspects of Form, Tonality, and Texture in the ''Farewell'' Piano Sonatas of Beethoven and Dussek Kyoung Cha A Doctoral Research Project Submitted to The College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance Peter Amstutz, D. M. A., Chair and Research Advisor William Haller, D. M. A. James Miltenberger, D. M. A. Keith Jackson, D. -

Compact Disc 2 70'11 Compact Disc 1 62'06

Compact Disc 1 62’06 Compact Disc 2 70’11 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685–1759 CARL DITTERS VON DITTERSDORF 1739–1799 Harp Concerto in B flat HWV294 Harp Concerto in A 1 I. Andante – Allegro 4’18 1 I. Allegro molto 6’37 2 II. Larghetto 5’30 2 II. Larghetto 9’10 3 III. Allegro moderato 2’32 3 III. Rondo: Allegretto 3’33 Charlotte Balzereit harp · Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra / Nicol Matt Recording: Summer & Autumn 2004, Evangelische Schlosskapelle Solitude, Stuttgart, Germany JOHANN GEORG ALBRECHTSBERGER 1736–1809 P 2006 Brilliant Classics Harp Concerto in C 4 I. Allegro moderato 6’28 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 1756–1791 5 II. Adagio 9’45 Flute & Harp Concerto in C K299 6 III. Allegro 3’15 4 I. Allegro 9’35 5 II. Andantino 8’10 Partita in F 6 III. Rondo: Allegro 9’30 7 I. Presto 3’49 8 II. Adagio un poco 7’02 Marc Grauwels flute · Giselle Herbert harp · Les Violins du Roy / Bernard Labadie 9 III. Menuetto 2’43 Recording: 1994, Muziekcentrum Frits Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands 10 IV. Finale: Allegro 4’05 P 2015 Brilliant Classics GEORG CHRISTOPH WAGENSEIL 1715–1777 FRANÇOIS-ADRIEN BOIELDIEU 1775–1834 Harp Concerto in G Harp Concerto in C 11 I. Allegro 3’50 7 I. Allegro brillante 10’58 12 II. Andante 4’37 8 II. Andante lento – 4’07 13 III. Vivace 5’11 9 III. Rondo: Allegro agitato 7’02 Jutta Zoff harp · Staatskapelle Dresden / Siegfried Kurz Jana Boušková harp · Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim / Vladislav Czarnecki Recording: April & May 1981, Lukaskirche, Dresden, Germany Recording: 7–10 September 1998 P 1983 Edel Classics GmbH · Licensed from Edel Germany GmbH P 1999 ebs records GmbH · Licensed from Bayer Records 3 Compact Disc 3 70’55 Compact Disc 4 62’13 JEAN-BAPTISTE KRUMPHOLZ 1742–1790 CARL REINECKE 1824–1910 Harp Concerto No.6 Op.9 Harp Concerto in E minor Op.182 1 I. -

Sc~Ol Ofmusic PROGRAM

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University MICHAEL P. HAMMOND PREPARATORY PROGRAM Concert CXXIII Saturday, December 8, 2007 2:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfk1eherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM The Loch Ness Monster Nancy and Randall Faber Coconut Shuffle Katie Hasley, piano (student of Wenli Zhou) March Slav Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Ii Hello Mudduh, Hello Fadduh! Lou Busch "A Letter from Camp" (1910-1979) Hunter Hasley, piano (student of Wenli Zhou) Pumpkin Boogie Nancy and Randall Faber Fur Elise Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) trans. Nancy and Randall Faber Emre Kilic, piano (student of Wenli Zhou) Minuet in G Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) La Gracieuse, Op. 100 "Grace" Frederic Burgmiiller (1806-1874) Marcus Manca, piano (student of Wenli Zhou) La Tarentella, Op. JOO Frederic Burgmiiller Katharine Patrick, piano (student of Wenli Zhou) Carefree Waltz German Traditional Turkish March Ludwig van Beethoven trans. Nancy and Randall Faber Zachary Hojabri, piano (student ofRobert Moeling) I Burleske Leopold Mozart ~ (1719-1844) Gavotte Daniel Speer I (1636-1707) Oki Nakazawa, piano (student of Sohyoung Park) The Knight Errant, Op. JOO No.15 Frederic Burgmuller Peter Jalbert, piano (student of Sohyoung Park) Romance Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Allegretto Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Helen Jang, piano (student of Sohyoung Park) Sonatina in G Major, Op. 20 No. I Jan Ladislav Dussek I Allegro non tanto (1760-1812) II Rondo. Allegretto Tempo di Minuetto Devin Gu, piano (student of Sohyoung Park) German Dance Ludwig van Beethoven Prelude in C Major Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) Toccatina Dmitri Kabalevsky (1904-1987) Vydia Sivaramakrishnan, piano (student ofRobert Moeling) Sonata in D Major Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) Little Shepherd Claude Debussy (1862-1918) JinAh Kim, piano (student of Sohyoung Park) Sonata in C Major, K. -

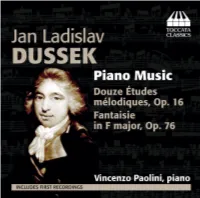

Toccata Classics TOCC0275 Notes

P JAN LADISLAV DUSSEK: PIANO MUSIC by Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald The cover of this disc shows a mezzotint portrait of Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760–1812) published by John Bland in London in 1793. Bland published prints of a number of prominent musicians of the day, including Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Johann Peter Salomon (1745–1815), Ignaz Pleyel (1757–1831) and Muzio Clementi (1752–1832). The inclusion of Dussek in this series reflects his contemporary prominence. In Alan Davison’s view, ‘the fact that Dussek is shown resplendent in mezzotint would have signalled him as a noteworthy sitter. The portrait emphasises [Dussek’s] youth and physical beauty’; and it matches one contemporary description of him as ‘a handsome man, good dispositioned, mild and pleasing in his demeanour and agreeable’.1 The prestige and glamour Dussek achieved in his lifetime – embodied in the Bland print – contrasts starkly with his comparative modern obscurity. With perhaps exaggerated pessimism, the current Wikipedia entry asserts that ‘[n]either [Dussek’s] playing style nor his compositions […] had any notable lasting impact’ and that ‘his music […] is now virtually unknown’.2 Typically for his time, Dussek pursued a multifaceted peripatetic career that encompassed piano performance, composition, teaching, administration and publishing in his native Bohemia, the Netherlands, Paris and London. His compositional output, strongly weighted towards the piano, includes a body of solo sonatas, a plethora of miscellaneous piano works, chamber music (including a piano quartet, piano quintet and three string quartets) and about eighteen piano concertos. Dussek also wrote various works for the harp, including a number of concertos: in August 1792 he married the famous Scottish harpist Sophia Corri (1775–1831), a composer in her own right. -

10-15-11 Frederick Moyer Prog

Williams College Department of Music Frederick Moyer, Piano Notes and Footnotes Jan Ladislav Dussek Sonata in D Major, Op. 31, No. 2 (1760-1812) I. Allegro non tanto II. Adagio con espressione III. Allegro non troppo Felix Mendelssohn Prelude and Fugue in E Minor, Op. 35, No. 1 (1809-1847) Sergei Rachmaninoff Three Preludes from Op. 23 (1873-1943) G Minor D Major B flat Major ***intermission*** Robert Schumann From Sonata No. 3 in F Minor, Op. 14 (1810-1856) Quasi Variazioni (Andantino de Clara Wieck) Presto Possibile – Original Finale movement (unpublished) Deciphered by F. Moyer, Paul E. Green, Jr. & Rafael Green - 2010 Frederic Chopin Ballade No. 3 in A flat Major, Op. 47 (1810-1849) Franz Liszt “Un Sospiro” from Three Concert Etudes, S. 144 (1811-1886) Franz Liszt Paganini Etude No. 3 “La Campanella” (1811-1886) (Arrangement by Ferruccio Busoni) Saturday, October 15, 2011 8:00 p.m. Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Upcoming Events: See music.williams.edu for full details and to sign up for the weekly e-newsletters. 4:15pm Workshop: Anonymous 4 Thompson Memorial Chapel 10/21 8pm Visiting Artist: Anonymous 4 Thompson Memorial Chapel 10/24 4:15pm Class of 1960 Lecture with Prof. Louise Meintjes Room 30, Bernhard 10/26 12:15pm MIDWEEKMUSIC Greylock Hall 10/28 8pm Williams Chamber Players Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall 10/29 8pm Williams Jazz Ensemble ’62 Center, MainStage * Please turn off or mute cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. Frederick Moyer, Biography During nearly 30 years as a full-time concert pianist, Frederick Moyer has carved out a vital and unusual career characterized by an extremely exacting approach to music-making and a wide variety of interests. -

1 Heading Pages

CDs containing Music Recordings are included in volume 1 of the print copy held in the Elder Music Library Notated and Implied Piano Pedalling c.1780–1830 Julie Haskell Volume Two Portfolio of Recorded Performances and Exegesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy …. Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide January 2011 Table of Contents Volume Two: Exegesis Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii Volume One: Recordings.......................................................................................................................... iv Pianos used in the Recordings ....................................................................................... v CD 1 ............................................................................................................................ vi CD 2 ............................................................................................................................vii CD 3 ...........................................................................................................................viii CD 4 ............................................................................................................................ ix CD 5 ............................................................................................................................ ix CD 6 ............................................................................................................................