Notes on the Powdery Mildews of Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Powdery Mildew on Tomatoes

NEW POWDERY MILDEW ON TOMATOES Heather Scheck, Plant Pathologist Ag Commissioner’s Office, Santa Barbara County POWDERY MILDEW BIOLOGY Powdery mildew fungi are obligate, biotrophic parasites of the phylum Ascomycota of the Kingdom Fungi. The diseases they cause are common, widespread, and easily recognizable Individual species of powdery mildew fungi typically have a narrow host range, but the ones that infect Tomato are exceptionally large. Photo from APS Net POWDERY MILDEW BIOLOGY Unlike most fungal pathogens, powdery mildew fungi tend to grow superficially, or epiphytically, on plant surfaces. During the growing season, hyphae and spores are produced in large colonies that can coalesce Infections can also occur on stems, flowers, or fruit (but not tomato fruit) Our climate allows easy overwintering of inoculum and perfect summer temperatures for epidemics POWDERY MILDEW BIOLOGY Specialized absorption cells, termed haustoria, extend into the plant epidermal cells to obtain nutrition. Powdery mildew fungi can completely cover the exterior of the plant surfaces (leaves, stems, fruit) POWDERY MILDEW BIOLOGY Conidia (asexual spores) are also produced on plant surfaces during the growing season. The conidia develop either singly or in chains on specialized hyphae called conidiophores. Conidiophores arise from the epiphytic hyphae. This is the Anamorph. Courtesy J. Schlesselman POWDERY MILDEW BIOLOGY Some powdery mildew fungi produce sexual spores, known as ascospores, in a sac-like ascus, enclosed in a fruiting body called a chasmothecium (old name cleistothecium). This is the Teleomorph Chasmothecia are generally spherical with no natural opening; asci with ascospores are released when a crack develops in the wall of the fruiting body. -

Erysiphe Salmonii (Erysiphales, Ascomycota), Another East Asian Powdery Mildew Fungus Introduced to Ukraine Vasyl P

Гриби і грибоподібні організми Fungi and Fungi-like Organisms doi: 10.15407/ukrbotj74.03.212 Erysiphe salmonii (Erysiphales, Ascomycota), another East Asian powdery mildew fungus introduced to Ukraine Vasyl P. HELUTA1, Susumu TAKAMATSU2, Siska A.S. SIAHAAN2 1 M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2 Tereshchenkivska Str., Kyiv 01004, Ukraine [email protected] 2 Department of Bioresources, Graduate School, Mie University 1577 Kurima-Machiya, Tsu 514-8507, Japan [email protected] Heluta V.P., Takamatsu S., Siahaan S.A.S. Erysiphe salmonii (Erysiphales, Ascomycota), another East Asian powdery mildew fungus introduced to Ukraine. Ukr. Bot. J., 2017, 74(3): 212–219. Abstract. In 2015, a powdery mildew caused by a fungus belonging to Erysiphe sect. Uncinula was recorded on two species of ash, Fraxinus excelsior and F. pennsylvanica (Oleaceae), from Ukraine (Kyiv, two localities). Based on the comparative morphological analysis of Ukrainian specimens with samples of Erysiphe fraxinicola and E. salmonii collected in Japan and the Far East of Russia, the fungus was identified as E. salmonii. This identification was confirmed using molecular phylogenetic analysis. This is the first report of E. salmonii not only in Ukraine but also in Europe. It is suggested that the records of E. fraxinicola from Belarus and Russia could have been misidentified and should be corrected to E. salmonii. In 2016, the fungus was found not only in Kyiv but also outside the city. The development of the fungus had symptoms of a potential epiphytotic disease. Thus, it may become invasive in Ukraine and spread to Western Europe in the near future. -

Effect of Environmental Conditions and Phenology in the Dispersal of Secondary Erysiphe Necator Conidia in a Vineyard

Vitis 58 (Special Issue), 49–58 (2019) DOI: 10.5073/vitis.2019.58.special-issue.49-58 Effect of environmental conditions and phenology in the dispersal of secondary Erysiphe necator conidia in a vineyard E. GONZÁLEZ-FERNÁNDEZ1), A. PIÑA-REY1), M. FERNÁNDEZ-GONZÁLEZ1), 2) and F. J. RODRÍGUEZ-RAJO1) 1) CITACA, Agri-Food Research and Transfer Cluster, Sciences Faculty, University of Vigo, Ourense, Spain 2) Earth Sciences Institute (ICT), Pole of the Faculty of Sciences University of Porto, Porto, Portugal Summary ades, we are witnessing a huge agriculture mechanization and a rapid modernization of the European viticulture sector An integrated powdery mildew management strat- because of investments in this primary economical area. egy to identify the principal moments of secondary The biggest vineyard surface at world level was placed in Erysiphe necator conidia dispersal in a vineyard based Spain (13 %) been the third largest wine producer country on aerobiological, phenological and meteorological data (13 %) just below Italy (18 %) and France (17 %) (Mapama was developed. An adaptation of the physiological P-days 2016). Diseases and pests of crops affect potential yields and model was conducted to obtain a descriptive equation economic profits. A co-evolution of plants and their parasitic for the prediction of the advantageous meteorological fungi was detected, which explains their fitted adaptation conditions for Erysiphe necator conidia dispersal in the to the real changing conditions of the vineyard agrosystem. vineyards of the Ribeiro Designation of Origin area. The specific bioclimatological conditions of Northwest Moreover, a regression model was developed to predict Spain favour the development of fungal phytopathogenic the conidia concentration as a function of the weather diseases, which are responsible for remarkable annual yield and aerobiological variables with the highest influence loss. -

The Risk Assessment Index in Grape Powdery Mildew Control Decisions and the Effect of Temperature and Humidity on Conidial Germination of Erysiphe Necator C

Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2007 5(4), 522-532 Available online at www.inia.es/sjar ISSN: 1695-971-X The risk assessment index in grape powdery mildew control decisions and the effect of temperature and humidity on conidial germination of Erysiphe necator C. E. Bendek, P. A. Campbell, R. Torres, A. Donoso and B. A. Latorre* Facultad de Agronomía e Ingeniería Forestal. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Casilla 306. Santiago. Chile Abstract Powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) is a major disease of grapevines (Vitis vinifera) in Chile. Severe outbreaks have occurred recently despite the use of strict fungicide programs to control it. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the infection risk assessment index (RAI), to predict conditions for E. necator infection, and to study the effect of temperature (T), relative humidity (RH) and free moisture (FM) on conidial germination and disease development. Conidial germination was affected by T, RH, and FM. There were significant (p < 0.001) interactions between E. necator isolates and T and between isolates and RH. Conidial germination was optimal at 25°C. There was no germination at 5°C and 35°C. At 20°C, conidia germinated at a low RH (33-35%). Germination increased at a RH between 47 and 90% but decreased at higher RHs. Powdery mildew development on Carmenere, Chardonnay, and Merlot vines increased linearly from 6°C to 23°C. These grape cultivars were all equally susceptible to E. necator. Incubation periods varied. It was 13 to 14 d at 20°C or 23°C, 19 to 24 d at 10°C, and more than 23 d at 6°C. -

Occurrence of the Fungi from the Genus Ampelomyces – Hyperparasites of Powdery Mildews (Erysiphales) Infesting Trees and Bushes in the Municipal Environment

Vol. 80, No. 2: 169-174 , 2011 ACTA SOCIETATIS BOTANICORUM POLONIAE 169 OCCURRENCE OF THE FUNGI FROM THE GENUS AMPELOMYCES – HYPERPARASITES OF POWDERY MILDEWS (ERYSIPHALES) INFESTING TREES AND BUSHES IN THE MUNICIPAL ENVIRONMENT EWA SUCHARZEWSKA , M ARIA DYNOWSKA , A NETA BOŻENA KEMPA Department of Mycology, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn Oczapowskiego 1A,10-719 Olsztyn-Kortowo, Poland e-mail: [email protected] (Received: March 23, 2010. Accepted: July 19, 2010) ABSTRACT The studies refer to the phenomenon of hyperparasitism in the municipal environment. The paper presents the occurrence of fungi of the genus Ampelomyces on Erysiphales – important group of phytopathogenic fungi. For the first time in Poland analyzed degree of infestation of Erysiphales mycelium by Ampelomyces and effect of the hyperparsites on the degree of infestation plants by Erysiphales . The high participation of the Ampelomyces was noted in each year of the study. Substantial differences were noted in the occurrence of Ampelomyces depending on the developmental stage of the host fungi and considerable differences in the prevalence of the hyperparasites on particular Erysiphales species. In all cases examined , the mean index of infestation of host plants by Erysiphales was higher than the mean degree of infestation of powdery mildew mycelium by Ampelomyces . The results indicate that under natural conditions they do not play any significant role in the reduction of the degree of infestation of host plants by Erysiphales and do not disturb drastically their life cycle. KEY WORDS: Ampelomyces , Erysiphales, hyperparasites, municipal environment. INTRODUCTION Kiss at al. 2004). In turn , still little attention is paid to the ecology of those parasites , their occurrence and effect on Fungi from the genus Ampelomyces (Ces. -

![Full Text [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4350/full-text-pdf-2764350.webp)

Full Text [PDF]

® The European Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology ©2011 Global Science Books Powdery Mildews on Ornamental Trees and Shrubs in Norway Venche Talgø1* • Leif Sundheim1 • Halvor B. Gjærum1 • Maria Luz Herrero1 • Aruppillai Suthaparan2 • Brita Toppe1 • Arne Stensvand1 1 Norwegian Institute for Agricultural and Environmental Research, Plant Health and Plant Protection Division, 1432 Ås, Norway 2 Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, 1432 Ås, Norway Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents powdery mildew species recorded on woody ornamentals, with special emphasis on the latest arrivals; Erysiphe flexuosa on horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), Erysiphe syringae-japonicae on lilac (Syringa vulgaris) and Podosphaera spiraeae on white spirea (Spiraea betulifolia). The two former were found in 2006, while the latter was first detected in 2008. Chasmothecia (formerly named cleistothecia) were not found on white spirea until 2010. Several locations seemed to have optimal conditions for development of powdery mildew diseases in 2006. That year the long established Sawadaea bicornis on sycamore maple (Acer pseudo- platanus), was found for the first time on tatarian maple (Acer tataricum ssp. ginnala) and one cultivar from hedge maple (Acer campestre ‘Red Shine’). Also several species and cultivars of Rhododendron had massive attacks of powdery mildew in 2006. In 2010, chasmothecia of E. azaleae were found on severely affected R. ‘Magnifica’ in western -

A Revised List of South African Erysiphaceae (Powdery Mildews) and Their Host Plants

566 S.Afr.J.Bot., 1993, 59(6): 566 - 568 A revised list of South African Erysiphaceae (powdery mildews) and their host plants G.J.M.A. Gorter Mycology Unit, Biosystematics Division, Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X134, Pretoria, 0001 Republic of South Africa Received 17 May 1993; revised 5 July 1993 A new list of South African Erysiphaceae, wh ich includes nomenclatural changes and newly recorded species and host plants, is presented with a few introductory remarks. 'n Nuwe Iys van Suid-Afrikaanse Erysiphaceae word aangebied wat behalwe nomenklatuurveranderings en nuut aangetekende spesies en gasheerplante, ook enkele inleidende opmerkings bevat. Keywords: Erysiphaceae, host plants, South Africa. Introduction be maintained as a separate species. The more recently The monumental new monograph of the Erysiphales by described P. cassiae Gorter & Eicker (1986) and P. gorteri Braun (1987), a publication which only recently became Eicker (1988) have aberrant spore shapes as well and are available to the author, has necessitated some nomenclatural therefore considered separate taxa. changes in the scientific names recorded by me in my com With regard to Uncinula praeterita Marasas & Schumann, pilation of South African powdery mildew fungi published after due consideration of all taxonomically relevant fea in 1988 (Gorter 1988). The description of new local taxa tures, I am of the opinion that Braun has been premature in (Eicker 1988; Gorter 1989b; Gorter & Marasas 1988) as giving it the status of a variety of Uncinula udaiparensis well as the recording of more host plants, of which some Bhatnagar & Kothari. Although both Uncinulas are no doubt have already been published (Gorter 1989a), are additional closely related, there are clear differences in the size of the reasons for presenting a new list. -

Fungicide and Clay Treatments for Control of Powdery Mildew

HORTSCIENCE 41(1):176–182. 2006. disrupted by fungicides which in turn could affect wine quality. An important fungal plant pathogen of Fungicide and Clay Treatments for grapes is Erysiphe necator Schwein. var. necator (formerly Uncinula necator) which Control of Powdery Mildew Infl uence causes powdery mildew (Pearson, 1988) reducing yield and quality of juice and wine Wine Grape Microfl ora from infected grapes (Calonnec et al., 2004; Gadoury et al., 2001). Powdery mildew is Peter Sholberg, Colleen Harlton, Julie Boulé, Paula Haag controlled by several fungicides belonging Pacifi c Agri-Food Research Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 4200 to the demethylation-inhibiting, strobilurin, Highway 97, Summerland, B.C. V0H 1Z0, Canada and quinoxyfen classes (Sholberg, 2004). It is also controlled by a number of organically Additional index words. bacteria, ‘Chancellor’, fungi, ‘Pinot noir’, pseudomonads, produced materials in which sulphur is the ‘Riesling’, Uncinula necator, Vitis vinifera, yeast most important member. Some other organics are mineral and vegetable oils (Northover and Abstract. There is very little information on the interaction of wine grape microfl ora with Schneider, 1996), potassium silicate (Reynolds fungicides used to control grape diseases. The objective of this study was to determine et al., 1996), and clay (Ehret et al., 2001; Shol- how fungicides used in a standard grape pest management program and an experimental berg and Boulé, 2001). In addition to powdery clay being developed for control of powdery mildew affect grape microfl ora. Grape leaves mildew, bunch rot and phomopsis cane and leaf and fruit were surveyed for bacteria, fungi and yeast six times over the growing season spot are important in grape pest management. -

Subdivision: Ascomycotina, Class: Hemiascomycetes (Taphrinales)

Subdivision: Ascomycotina, class: Hemiascomycetes (Taphrinales), class: Plectomycetes (Eurotiales), class: Pyrenomycetes (Erysiphales, Clavicepitales), class: Loculoascomycetes (Pleosporales) General characters Mycelium is well developed branched and septate. Yeast is single celled organism. Septum has a central pore. Cell wall is made up of chitin. Asexual spores are non-motile conidia. Sexual spores are ascospores. Ascospores are usually 8 in an ascus. They are produced endogenously inside the ascus. Key to the classes of Ascomycotina Ascocarps and ascogenous hyphae absent, thallus mycelial or yeast-like - Hemiascomycetes Ascocarps and ascogenous hyphae present, Thallus mycelial: Asci bitunicate, ascocarp an ascostroma - Loculoascomycetes Asci typically unitunicate, if bitunicate, ascocarp as apothecium: Ascocarp a cleistothecium, asci evanescent and scattered - Plectomycetes Asci regularly arranged as basal or peripheral layer in the ascocarp Insect parasites - Laboulbeniomycetes Not insect parasites, Ascocarp perithecium - Pyrenomycetes Ascocarp apothecium – Discomycetes Class: Hemiascomycetes The class is characterized by the lack of ascocarp, vegetative phase comprising of unicellular thallus or poorly developed mycelium. It is divided into three orders: 1. Asci developing parthenogenetically from a single cell or directly from a zygote formed by population of 2 cells - Endomycetales 2. Asci developing from ascogenous cells, forming a palisade like layer - Taphrinales 3. Asci developing in a compound spore sac (synascus), produced -

Knockdown of MLO Genes Reduces Susceptibility to Powdery Mildew in Grapevine

OPEN Citation: Horticulture Research (2016) 3, 16016; doi:10.1038/hortres.2016.16 www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Knockdown of MLO genes reduces susceptibility to powdery mildew in grapevine Stefano Pessina1,2, Luisa Lenzi1,3, Michele Perazzolli1, Manuela Campa1, Lorenza Dalla Costa1, Simona Urso4,5, Giampiero Valè4,5, Francesco Salamini1, Riccardo Velasco1 and Mickael Malnoy1 Erysiphe necator is the causal agent of powdery mildew (PM), one of the most destructive diseases of grapevine. PM is controlled by sulfur-based and synthetic fungicides, which every year are dispersed into the environment. This is why PM-resistant varieties should become a priority for sustainable grapevine and wine production. PM resistance can be achieved in other crops by knocking out susceptibility S-genes, such as those residing at genetic loci known as MLO (Mildew Locus O). All MLO S-genes of dicots belong to the phylogenetic clade V, including grapevine genes VvMLO7, 11 and 13, which are upregulated during PM infection, and VvMLO6, which is not upregulated. Before adopting a gene-editing approach to knockout candidate S-genes, the evidence that loss of function of MLO genes can reduce PM susceptibility is necessary. This paper reports the knockdown through RNA interference of VvMLO6, 7, 11 and 13. The knockdown of VvMLO6, 11 and 13 did not decrease PM severity, whereas the knockdown of VvMLO7 in combination with VvMLO6 and VvMLO11 reduced PM severity up to 77%. The knockdown of VvMLO7 and VvMLO6 seemed to be important for PM resistance, whereas a role for VvMLO11 does not seem likely. Cell wall appositions (papillae) were present in both resistant and susceptible lines in response to PM attack. -

Erysiphaceae of Japan

Title ERYSIPHACEAE OF JAPAN Author(s) HOMMA, Yasu Citation Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido Imperial University, 38(3), 183-461 Issue Date 1937-02-28 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/12712 Type bulletin (article) File Information 38(3)_p183-461.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP ERVSIPHACEAE OF JAPAN By Yasu HOMMA Contents Page Introduction 186 General Part Morphology and Physiology. 188 Mycelia ................................................. 188 Conidia ................................................. 191 Forms .............................................. 192 Formation of conidia ................................. 194 Fibrosin bodies ...................................... 197 Germination of conidia ............................... 198 Perithecia ............................................... 199 Forms and appendages............ ..... .............. 199 Structure ........................................... 201 Formation of perithecia .............................. 202 Asci and ascospores ...................................... 208 Hibernation .............................................. 208 Host and Parasitism ......................................... 209 Infection ............................................ 209 Correlation of the development of the host plants to that of the powdery mildew .......... ,.................. 214 Special~ation and resistance .................................. 239 Infection experiments with the conidia ................ 239 -

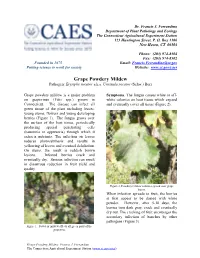

Grape Powdery Mildew Pathogen: Erysiphe Necator A.K.A

Dr. Francis J. Ferrandino Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8504 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes Grape Powdery Mildew Pathogen: Erysiphe necator a.k.a. Uncinula necator (Schw.) Burr Grape powdery mildew is a major problem Symptoms. The fungus causes white or off- on grapevines (Vitis spp.) grown in white colonies on host tissue which expand Connecticut. The disease can infect all and eventually cover all tissue (Figure 2). green tissue of the plant including leaves, young stems, flowers and young developing berries (Figure 1). The fungus grows over the surface of the host tissue, periodically producing special penetrating cells (haustoria or appresoria) through which it extracts nutrients. The infection on leaves reduces photosynthesis and results in yellowing of leaves and eventual defoliation. On stems, the result is reddish brown lesions. Infected berries crack and eventually dry. Serious infection can result in disastrous reduction in fruit yield and quality. Figure 2. Powdery mildew colonies spread over grape leaves. When infection spreads to fruit, the berries at first appear to be dusted with white powder. However, after 5-10 days, the berries turn dark gray, crack and eventually dry out. The cracking of fruit encourages the secondary infection of bunches by other pathogens (Figure 3). Figure 1. Powdery mildew affects all green parts of the grapevine. Grape Powdery Mildew Francis J. Ferrandino The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes) Figure 3.