Exploring Aspects of Cognitive Development and Mental Health Awareness As Part of Health Promotional Goal in Snooker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Main

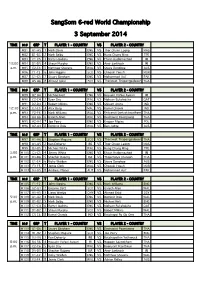

SangSom 6-red World Championship 3 September 2014 TIME M # GRP T PLAYER 1 - COUNTRY VS PLAYER 2 - COUNTRY M81 A1-A5 1 Mark Davis ENG VS Thor Chuan Leong MAS M82 B1-B5 2 Mark Selby ENG VS Hung Chung Ming TPE M83 C1-C5 3 Barry Hawkins ENG VS Ehsan Hydarinezhad IRI 10:00 M84 D1-D5 4 Shaun Murphy ENG VS Amir Sarkhosh IRI a.m. M85 E2-E4 5 Matthew Stevens WAL VS Steve Donohoe AUS M86 F1-F5 6 John Higgins SCO VS Chaouki Yousfi MOR M87 G1-G5 7 Stuart Bingham ENG VS Mohammad Asif PAK M88 H5-H6 8 Ahmed Galal EGY VS Thanawat Tirapongpaiboon THA TIME M # GRP T PLAYER 1 - COUNTRY VS PLAYER 2 - COUNTRY M89 B2-B4 1 Michael Holt ENG VS Hossein Vafaei Ayouri IRI M90 C2-C4 2 Ryan Day WAL VS Mohsen Bukshaisha QAT M91 D2-D4 3 Robert Milkins ENG VS Shivam Arora IND 12:30 M92 E3-E5 4 Alex Borg MAL VS Kamal Chawla IND p.m. M93 F2-F6 5 Mark Williams WAL VS Kritsanut Lertsattayathorn THA M94 G4-G6 6 Gareth Allen WAL VS Dechawat Poomjaeng THA M95 H2-H4 7 Joe Perry ENG VS Kacper Filipiac POL M96 A2-A4 8 Dominic Dale WAL VS Ben Judge AUS TIME M # GRP T PLAYER 1 - COUNTRY VS PLAYER 2 - COUNTRY M97 H1-H6 1 Stephen Maguire SCO VS Thanawat Tirapongpaiboon THA M98 A3-A5 2 Ken Doherty IRE VS Thor Chuan Leong MAS M99 B3-B5 3 Michael White WAL VS Hung Chung Ming TPE 3:00 M100 C3-C5 4 Jimmy White ENG VS Ehsan Hydarinezhad IRI p.m. -

ORDER of PLAY Wednesday 13 November 2019

19.com Northern Ireland Open 2019 ORDER OF PLAY Wednesday 13 November 2019 START TIME: 10:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker Maike Kesseler TABLE 1 92 Barry Hawkins Michael Holt Leo Scullion TABLE 2 72 Liang Wenbo Tian Pengfei Nico De Vos TABLE 3 69 Yan Bingtao Marco Fu Luise Kraatz TABLE 4 67 Si Jiahui Chen Zifan Alex Crisan TABLE 5 71 Jak Jones Anthony Hamilton Rob Spencer TABLE 6 70 Rod Lawler Andrew Higginson Terry Camilleri TABLE 7 83 Robbie Williams Hammad Miah Malgorzata Kanieska TABLE 8 86 Martin O'Donnell Alexander Ursenbacher Monika Sulkowska START TIME: 13:00 Not before 13:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 75 Matthew Selt Luca Brecel Glen Sullivan-Bisset 76 Soheil Vahedi Ken Doherty John Pellew 77 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh Mei Xiwen Greg Coniglio 78 Mitchell Mann Harvey Chandler Proletina Velichkova 80 Chen Feilong Billy Castle REFEREE TBC 88 Ian Burns Scott Donaldson REFEREE TBC Kevin Dabrowski TABLE 1 74 Mark Selby Matthew Stevens Plamena Manolova TABLE 2 68 Ali Carter Li Hang Colin Humphries START TIME: 14:00 Roll-on Roll-off Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 79 Mark Davis Stephen Maguire REFEREE TBC 84 Joe Perry Ross Bulman REFEREE TBC TABLE 1 66 Judd Trump Zhang Anda REFEREE TBC TABLE 2 73 Peter Ebdon Kyren Wilson REFEREE TBC START TIME: 16:30 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker TABLE 1 87 Jordan Brown Stuart Bingham REFEREE TBC TABLE 2 82 Mark Joyce Jackson Page REFEREE TBC Powered by Sportradar | http://www.sportradar.com | Tuesday, Nov 12 2019 23:45:30 | © World Snooker. -

ORDER of PLAY Thursday 16 February 2017

Coral Welsh Open ORDER OF PLAY Thursday 16 February 2017 START TIME: 12:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker Rob Spencer TABLE 1 103 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh Barry Hawkins Peter Williamson TABLE 2 100 Graeme Dott Lee Walker Luise Kraatz TABLE 3 107 Dominic Dale Igor Figueiredo Terry Camilleri TABLE 4 97 Mark Davis Fergal O'Brien Malgorzata Kanieska TABLE 5 104 Anthony Hamilton Craig Steadman Tatiana Woollaston TABLE 6 99 Zhou Yuelong Ross Muir Glen Sullivan-Bisset TABLE 7 98 Jimmy Robertson Scott Donaldson Jan Scheers TABLE 8 108 Stuart Carrington Robin Hull Haydn Parry START TIME: 13:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker Colin Humphries TABLE 1 101 Judd Trump Jackson Page Peter Williamson TABLE 2 105 Stuart Bingham Ian Burns Nigel Leddie TABLE 3 106 Michael White Robbie Williams Martyn Royce TABLE 4 110 Mark Allen Mei Xiwen John Pellew TABLE 5 102 Allister Carter Hossein Vafaei Ayouri Alex Crisan TABLE 6 109 Josh Boileau Robert Milkins Joery Ector START TIME: 14:30 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker TABLE 1 112 Yan Bingtao Mark Selby REFEREE TBC TABLE 2 111 Kurt Maflin Mitchell Mann REFEREE TBC START TIME: 19:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 113 WINNER OF MATCH 97 WINNER OF MATCH 98 REFEREE TBC 114 WINNER OF MATCH 99 WINNER OF MATCH 100 REFEREE TBC 116 WINNER OF MATCH 103 WINNER OF MATCH 104 REFEREE TBC 118 WINNER OF MATCH 107 WINNER OF MATCH 108 REFEREE TBC START TIME: 20:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 115 WINNER OF MATCH 101 WINNER OF MATCH 102 REFEREE TBC 117 WINNER OF MATCH 105 WINNER OF MATCH 106 REFEREE TBC 119 WINNER OF MATCH 109 WINNER OF MATCH 110 REFEREE TBC 120 WINNER OF MATCH 111 WINNER OF MATCH 112 REFEREE TBC Powered by Sportradar | http://www.sportradar.com | Wednesday, Feb 15 2017 23:52:40 | © World Snooker.. -

Al-Neel, Pereira Shine in Markhiya's Win Over Shamal

NNBABA | Page 5 TTENNISENNIS | Page 6 Harden hits Sharapova heights as falls to Garcia in Rockets soar Stuttgart over Wolves fi rst round Wednesday, April 25, 2018 FOOTBALL Sha’baan 9, 1439 AH Unstoppable GULF TIMES Ronaldo the sole survivor of ‘BBC’ SPORT Page 3 FOCUS Impressive medal haul for Qatar at Arab athletics By Sports Reporter (Shot Put and Discus) in the recent On the last day of competition, Doha GCC Championship held in Kuwait, Rashid al-Suwaidi added a bronze student athlete Mohamed Ibrahim medal for his exploits in long jump and Moaaz maintained his fabulous form Team Qatar picked up their last medal, spire Academy student ath- to repeat the feat in the same events a bronze, thanks to the blistering pace letes led Qatar’s charge for in Amman. of Jaber Hilal al-Mamari in the 200m medals at the 18th Arab It was a similar tale with rising star sprint. Junior Athletics Champion- athlete, Muhand Saifeldin, who like Team Qatar’s athletes were among Aships held from April 19-22, 2018, at Mooaz, matched his two gold medal 423 competing at the 18th Arab Junior the Baccalaureate School in Amman, haul from the GCC Championship but Athletics Championships that featured Jordan. this time round also added a 800m win athletes from 16 countries across 44 The team brought home a total of in place of the 1,500m he won in Ku- events. seven medals on the back of some im- wait. His fi rst gold came in the 3,000m pressive performances that ensured steeplechase. -

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction. Day One €“ Rugby

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction. Day One – Rugby, Cricket, Tennis, Olympics, Boxing, Motor Sports, Rowing, Cycling & General Sports Wednesday 06 April 2011 11:00 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction. Day One – Rugby, Cricket, Tennis, Olympics, Boxing, Motor Sports, Rowing, Cycling & General Sports) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 bigbluetube - mf&g overall 30x 23" (G) Ideal for the snooker Snooker Cue - Joe Davis "Champion Snooker Cue- World's room/club Snooker Record 147" signature/endorsed full length one piece Estimate: £50.00 - £75.00 snooker cue 16.5oz c/w plastic case - overall 58" Estimate: £50.00 - £75.00 Lot: 5c Alex Higgins and Jimmy White "World Snooker Doubles Lot: 2 Champions" signed colour photograph print - titled "The Snooker/Billiard Cue - The Walter Lindrum World Champion Hurricane and The Whirlwind" and each signed in felt tip pen to Cue - Break 4,137" full length one piece cue 17oz c/w plastic the boarder - mf&g overall 19x 23" (G) Ideal for the snooker case - overall 58" room/club Estimate: £50.00 - £75.00 Estimate: £100.00 - £120.00 Lot: 3 Lot: 6 Snooker Cue - Sidney Smith "Tournament Snooker Cue" Rowland Patent Vic cast iron billiard /snooker cue wall rack and portrait signature/endorsed full length one piece snooker cue stand: spring loaded wall mount for 3 cues c/w matching cast 16.5oz c/w black japanned case - overall 57.5" iron base both stamped with monogram CJS and production no Estimate: £50.00 - £75.00 765 Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 Lot: 3a BCE Snooker cue signed c. -

Some Say That There Are Actually Four Players from Outside the U.K

Some say that there are actually four players from outside the U.K. that have been World Champion citing Australian Horace Lindrum, a nephew of Walter, who won the title in 1952. This event was boycotted by all the British professional players that year and for this reason many in the sport will not credit him with the achievement. The other three to make the list are first, Cliff Thorburn from Canada in 1980, defeating Alex Higgins 18 frames to 16. He also made the first 147 maximum break of the World Championships in his 1983 second round match against Terry Griffiths which he won 13 – 12. Third was Neil Robertson who won a never to be forgotten final against Scot Graeme Dott 18 frames to 13 in 2010. His route to the final had started with a match against Fergal O’Brien which he won 10 – 5. Next up was a heart stopping, come from behind win over Martin Gould after trailing 0 – 6 and again 5 – 11 before getting over the line 13 – 12. Steve Davis, multiple World Champion, was next and dispatched 13 – 5 which brought him to the semi finals and a 17 – 12 victory over Ali (The Captain) Carter. Third here but really second on the list is Ken Doherty from Eire who won the World title by beating Stephen Hendry, multiple World Champion winner from Scotland, at the Crucible in 1997 winning 18 - 12. Ken had previously become the I.B.S.F. amateur World Champion in 1989 by defeating Jon Birch of England 11 frames to 2 in the final held in Singapore. -

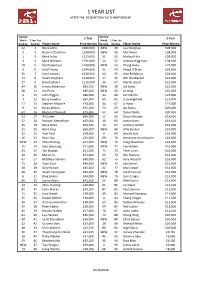

1 Year List After 2018 UK Championship

1 YEAR LIST AFTER THE 2018 BETWAY UK CHAMPIONSHIP Starting 1 Year Starting 1 Year World 1 Year List World 1 Year List Ranking Ranking Player Name Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Prize Money 12 1 Mark Allen £283,000 NEW 49 Luo Honghao £28,500 2 2 Ronnie O'Sullivan £220,000 NEW 50 Mei Xiwen £28,000 1 3 Mark Selby £213,000 31 51 Michael Holt £28,000 3 4 Mark Williams £191,000 54 52 Andrew Higginson £28,000 10 5 Neil Robertson £168,000 NEW 53 Zhang Anda £27,000 5 6 Judd Trump £144,500 51 54 Fergal O'Brien £26,600 26 7 Jack Lisowski £120,500 64 55 Alan McManus £24,000 13 8 Stuart Bingham £120,500 37 56 Ben Woollaston £22,600 27 9 David Gilbert £119,500 24 57 Martin Gould £22,000 34 10 Jimmy Robertson £90,725 NEW 58 Jak Jones £22,000 20 11 Joe Perry £90,500 NEW 59 Lu Ning £22,000 4 12 John Higgins £86,000 44 60 Kurt Maflin £21,600 7 13 Barry Hawkins £84,000 60 61 Liam Highfield £21,000 17 14 Stephen Maguire £78,000 36 62 Li Hang £21,000 9 15 Kyren Wilson £75,500 73 63 Ian Burns £20,600 67 16 Martin O'Donnell £74,000 63 64 Daniel Wells £20,500 11 17 Ali Carter £66,500 8 65 Shaun Murphy £19,500 52 18 Noppon Saengkham £65,000 39 66 Jamie Jones £19,100 41 19 Mark Davis £60,225 14 67 Anthony McGill £19,000 21 20 Mark King £60,000 NEW 68 Alfie Burden £19,000 32 21 Tom Ford £59,500 A 69 David Lilley £19,000 16 22 Ryan Day £56,500 69 70 Alexander Ursenbacher £16,600 NEW 23 Zhao Xintong £54,000 NEW 71 Craig Steadman £16,500 25 24 Xiao Guodong £51,600 NEW 72 Lee Walker £16,500 23 25 Yan Bingtao £51,500 75 73 Peter Lines £16,500 18 26 Marco Fu -

TOTAL PRIZE MONEY EARNED AFTER the 2017 BETFRED WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP Including Sanctioned Invitational Events, High Breaks and 147 Prizes

TOTAL PRIZE MONEY EARNED AFTER THE 2017 BETFRED WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP Including sanctioned invitational events, high breaks and 147 prizes 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 1 Stuart Bingham £571,436 1 Mark Selby £510,909 1 Mark Selby £933,428 2 Shaun Murphy £486,865 2 Neil Robertson £413,383 2 John Higgins £654,425 3 Judd Trump £453,199 3 John Higgins MBE £331,287 3 Ronnie O'Sullivan £472,750 4 Ronnie O'Sullivan OBE £451,450 4 Ronnie O'Sullivan OBE £302,100 4 Judd Trump £454,650 5 Neil Robertson £334,550 5 Mark Allen £298,700 5 Ding Junhui £416,081 6 Ricky Walden £273,356 6 Judd Trump £286,475 6 Stuart Bingham £376,159 7 Mark Selby £271,166 7 Ding Junhui £256,416 7 Barry Hawkins £356,225 8 Joe Perry £256,224 8 Kyren Wilson £219,700 8 Marco Fu £340,150 9 Mark Allen £238,000 9 Shaun Murphy £219,225 9 Shaun Murphy £279,375 10 Stephen Maguire £227,822 10 Barry Hawkins £210,525 10 Ali Carter £276,025 11 Mark Williams MBE £204,032 11 Marco Fu £193,209 11 Joe Perry £223,978 12 Barry Hawkins £173,496 12 Stuart Bingham £178,283 12 Liang Wenbo £220,656 13 John Higgins MBE £172,232 13 Liang Wenbo £162,636 13 Neil Robertson £207,625 14 Michael White £158,729 14 Martin Gould £155,775 14 Anthony McGill £204,900 15 Marco Fu £157,666 15 Joe Perry £150,934 15 Mark Allen £194,700 16 Robert Milkins £138,890 16 Mark Williams MBE £147,083 16 Mark Williams £177,639 17 Mark Davis £135,168 17 Ricky Walden £144,875 17 Ryan Day £162,990 18 Ding Junhui £134,500 18 Stephen Maguire £142,191 18 Kyren Wilson £147,275 19 Martin Gould £101,334 19 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh £125,347 19 Anthony -

Listado Actualizado El 5 De Julio De 2.015

147’S LISTADO ACTUALIZADO EL 5 DE JULIO DE 2.015 Nº AÑO FECHA JUGADOR RIVAL TORNEO 1.982 1 11/01/1982 Steve Davis John Spencer Classic 1.983 2 23/04/1983 Cliff Thorburn Terry Griffiths World Championship 1.984 3 28/01/1984 Kirk Stevens Jimmy White Masters 1.987 4 17/11/1987 Willie Thorne Tommy Murphy UK Championship 1.988 5 20/02/1988 Tony Meo Stephen Hendry Matchroom League 6 24/09/1988 Alain Robidoux Jim Meadowcroft European Open (Q) 1.989 7 18/02/1989 John Rea Ian Black Scottish Professional Championship 8 08/03/1989 Cliff Thorburn Jimmy White Matchroom League 1.991 9 16/01/1991 James Wattana Paul Dawkins World Masters 10 05/06/1991 Peter Ebdon Wayne Martin Strachan Open (Q)[17] 1.992 11 25/02/1992 James Wattana Tony Drago British Open 12 22/04/1992 Jimmy White Tony Drago World Championship 13 09/05/1992 John Parrott Tony Meo Matchroom League 14 24/05/1992 Stephen Hendry Willie Thorne Matchroom League 15 14/11/1992 Peter Ebdon Ken Doherty UK Championship 1.994 16 07/09/1994 David McDonnell Nic Barrow British Open (Q) 1.995 17 27/04/1995 Stephen Hendry Jimmy White World Championship 18 25/11/1995 Stephen Hendry Gary Wilkinson UK Championship 1.997 19 05/01/1997 Stephen Hendry Ronnie O'Sullivan Charity Challenge 20 21/04/1997 Ronnie O'Sullivan Mick Price World Championship 21 18/09/1997 James Wattana Pang Wei Guo China International 1.998 22 16/05/1998 Stephen Hendry Ken Doherty Premier League 23 10/08/1998 Adrian Gunnell Mario Wehrmann Thailand Masters (Q) 24 13/08/1998 Mehmet Husnu Eddie Barker China International (Q) 1.999 25 13/01/1999 -

February Newsletter

February 2021 www.pabsa.org [email protected] #WECUEASONE MEET AHMED IGOR FIGUEIREDO ‘FIND A CLUB’ ALY ELSAYAD FUNDRAISER PABSA Newsletter February 2021 #WeCueAsOne ‘Find a Club’ #WeCueAsOne After The Pan American Billiards and Snooker Association launched its new initiative, #WeCueAsOne last month which was aimed at supporting equality, inclusion and diversity in cue sports in the PABSA region, PABSA would now like to introduce its next stage of the this initiative. Introducing the ‘Find a Club’ section of the PABSA website. There is now a comprehensive and growing list of clubs and places to play snooker and billiards in the Pan American region available on the PABSA website. To support equality, inclusion and diversity within cue sports in the PABSA region, this new list of places available for players and fans to play and participate in cue sports will help with the growth, the knowledge and the engagement of cue sports. Whether you are new to snooker and billiards, looking to make a comeback to cue sports or whether you want to grow your knowledge of the game please take a look at this list for your nearest place to visit. With our growing association the ‘Find a Club’ list of places to play and interact with cue sports will continue to grow in the future and will continue to offer opportunities to players and fans in the Pan American region. If you know of any clubs or venues which offer access to at least one 12ft snooker table, then please email [email protected]. Thank you for your continued support. -

Listado Actualizado 6 De Diciembre De 2.015

147’S LISTADO ACTUALIZADO 6 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2.015 Nº AÑO FECHA JUGADOR RIVAL TORNEO 1.982 1 11/01/1982 Steve Davis John Spencer Classic 1.983 2 23/04/1983 Cliff Thorburn Terry Griffiths World Championship 1.984 3 28/01/1984 Kirk Stevens Jimmy White Masters 1.987 4 17/11/1987 Willie Thorne Tommy Murphy UK Championship 1.988 5 20/02/1988 Tony Meo Stephen Hendry Matchroom League 6 24/09/1988 Alain Robidoux Jim Meadowcroft European Open (Q) 1.989 7 18/02/1989 John Rea Ian Black Scottish Professional Championship 8 08/03/1989 Cliff Thorburn Jimmy White Matchroom League 1.991 9 16/01/1991 James Wattana Paul Dawkins World Masters 10 05/06/1991 Peter Ebdon Wayne Martin Strachan Open (Q)[17] 1.992 11 25/02/1992 James Wattana Tony Drago British Open 12 22/04/1992 Jimmy White Tony Drago World Championship 13 09/05/1992 John Parrott Tony Meo Matchroom League 14 24/05/1992 Stephen Hendry Willie Thorne Matchroom League 15 14/11/1992 Peter Ebdon Ken Doherty UK Championship 1.994 16 07/09/1994 David McDonnell Nic Barrow British Open (Q) 1.995 17 27/04/1995 Stephen Hendry Jimmy White World Championship 18 25/11/1995 Stephen Hendry Gary Wilkinson UK Championship 1.997 19 05/01/1997 Stephen Hendry Ronnie O'Sullivan Charity Challenge 20 21/04/1997 Ronnie O'Sullivan Mick Price World Championship 21 18/09/1997 James Wattana Pang Wei Guo China International 1.998 22 16/05/1998 Stephen Hendry Ken Doherty Premier League 23 10/08/1998 Adrian Gunnell Mario Wehrmann Thailand Masters (Q) 24 13/08/1998 Mehmet Husnu Eddie Barker China International (Q) 1.999 25 13/01/1999 -

World Snooker Championship 2016 FAQ

World Snooker Championship 2016 FAQ Written by Warren Pilkington, 14th April 2016. Will be updated as the tournament progresses where possible. Tournament What is the World Snooker Championship? The World Snooker Championship traditionally takes place in April and early May over a 17 day period with the final day being on the May Bank Holiday Monday. This year’s tournament starts Saturday 16th April and finishes Monday 2nd May 2016. Who is the defending champion? Stuart Bingham is the defending champion, who defeated Shaun Murphy 18-15. It was Stuart’s first World Championship title. Where is the tournament held? The tournament is held at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, and has been since 1977. It is often referred to as “the home of snooker” by fans, commentators and players alike. Why The Crucible Theatre? When promoter Mike Watterson’s wife saw a play at this intimate theatre in the round, she recommended it to him as an ideal venue. The closeness of the crowd to the stage (notably with two tables) and the 980 seated capacity gives it that special aura. What is the Crucible Curse? Since the World Championship has been held at the Crucible Theatre, no first time World Champion has gone on to win the championship the following year. This is known as the Crucible Curse. The closest anyone has come to breaking the Curse was Joe Johnson, who after winning in 1986 against Steve Davis lost to Steve Davis in the 1987 final 18-14. Who qualifies for the tournament automatically? The top 16 ranked players at the final event ranking cutoff (the China Open) will qualify.