Crucible's Greatest Crucible's Greatest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORDER of PLAY Wednesday 13 November 2019

19.com Northern Ireland Open 2019 ORDER OF PLAY Wednesday 13 November 2019 START TIME: 10:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker Maike Kesseler TABLE 1 92 Barry Hawkins Michael Holt Leo Scullion TABLE 2 72 Liang Wenbo Tian Pengfei Nico De Vos TABLE 3 69 Yan Bingtao Marco Fu Luise Kraatz TABLE 4 67 Si Jiahui Chen Zifan Alex Crisan TABLE 5 71 Jak Jones Anthony Hamilton Rob Spencer TABLE 6 70 Rod Lawler Andrew Higginson Terry Camilleri TABLE 7 83 Robbie Williams Hammad Miah Malgorzata Kanieska TABLE 8 86 Martin O'Donnell Alexander Ursenbacher Monika Sulkowska START TIME: 13:00 Not before 13:00 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 75 Matthew Selt Luca Brecel Glen Sullivan-Bisset 76 Soheil Vahedi Ken Doherty John Pellew 77 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh Mei Xiwen Greg Coniglio 78 Mitchell Mann Harvey Chandler Proletina Velichkova 80 Chen Feilong Billy Castle REFEREE TBC 88 Ian Burns Scott Donaldson REFEREE TBC Kevin Dabrowski TABLE 1 74 Mark Selby Matthew Stevens Plamena Manolova TABLE 2 68 Ali Carter Li Hang Colin Humphries START TIME: 14:00 Roll-on Roll-off Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker 79 Mark Davis Stephen Maguire REFEREE TBC 84 Joe Perry Ross Bulman REFEREE TBC TABLE 1 66 Judd Trump Zhang Anda REFEREE TBC TABLE 2 73 Peter Ebdon Kyren Wilson REFEREE TBC START TIME: 16:30 Table Match # Player 1 Result Player 2 Referee/Marker TABLE 1 87 Jordan Brown Stuart Bingham REFEREE TBC TABLE 2 82 Mark Joyce Jackson Page REFEREE TBC Powered by Sportradar | http://www.sportradar.com | Tuesday, Nov 12 2019 23:45:30 | © World Snooker. -

Steve Davis OBE Speaker Profile

Steve Davis OBE Six-Time World Snooker Champion Steve Davis OBE dominated the game of snooker throughout the 1980s and became a well known sporting personality. The six-time world snooker champion remains amongst the top 30 players and a member of the commentary team. Steve has diversified his career in recent years, becoming heavily involved in media and broadcasting with the BBC. Appearing on quiz shows including They Think It's All Over and A Question of Sport, Davis also regularly appears as a commentator and TV Presenter for the BBC's coverage of snooker. "Snooker Legend" In detail Languages Steve Davis has won a total of 28 ranking and 73 professional He presents in English. tournaments in his career. That's 73 wins from 100 finals! His most important wins are the six World Championships, six UK Want to know more? Championships and three Masters. He was the No.1 player in the Give us a call or send us an e-mail to find out exactly what he eighties, before Hendry came along. Steve was the first to make a could bring to your event. ratified maximum break in a major tournament who had a break of 147 against John Spencer in the Lada Classic at Oldham, Greater How to book him? Manchester in 1982. Simply phone or e-mail us. What he offers you Publications Steve is a compelling and engaging speaker, delivering anecdotal 2015 tales of his time in the limelight of snooker, as well as some of the Interesting: My Autobiography most famous moments during his era. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

World Rankings After the 2016 Baic Motor China Open

WORLD RANKINGS AFTER THE 2016 BAIC MOTOR CHINA OPEN Start Current Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Rankings 1 1 Mark Selby 650,041 2 2 Stuart Bingham 592,720 6 3 Shaun Murphy 475,058 3 4 Neil Robertson 461,360 7 5 Judd Trump 456,166 5 6 Ronnie O'Sullivan OBE 399,250 12 7 Mark Allen 386,700 13 8 John Higgins MBE 373,925 10 9 Ricky Walden 318,752 9 10 Joe Perry 306,083 8 11 Barry Hawkins 250,025 26 12 Martin Gould 229,759 14 13 Mark Williams MBE 208,625 11 14 Marco Fu 203,241 17 15 Michael White 190,033 15 16 Stephen Maguire 187,450 4 17 Ding Junhui 183,425 23 18 Liang Wenbo 178,101 56 19 Kyren Wilson 174,899 20 20 Ryan Day 156,557 16 21 Robert Milkins 154,644 35 22 David Gilbert 154,433 30 23 Matthew Selt 151,900 18 24 Graeme Dott 142,483 32 25 Ben Woollaston 141,949 19 26 Mark Davis 139,277 44 27 Luca Brecel 128,757 25 28 Michael Holt 123,533 22 29 Alan McManus 122,951 24 30 Anthony McGill 118,017 29 31 Allister Carter 115,050 31 32 Peter Ebdon 114,842 38 33 Jamie Jones 106,683 33 34 Dominic Dale 102,408 49 35 Thepchaiya Un-Nooh 98,307 41 36 Jimmy Robertson 96,972 36 37 Mark King 92,067 59 38 Tom Ford 84,933 27 39 Fergal O'Brien 83,575 47 40 Mark Joyce 78,091 42 41 Mike Dunn 77,530 43 42 Dechawat Poomjaeng 76,890 53 43 Jack Lisowski 76,749 39 44 Rod Lawler 76,224 82 45 Tian Pengfei 74,616 28 46 Matthew Stevens 73,368 21 47 Xiao Guodong 73,145 34 48 Gary Wilson 73,074 WORLD RANKINGS AFTER THE 2016 BAIC MOTOR CHINA OPEN Start Current Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Rankings 48 49 Andrew Higginson 72,858 46 50 Jamie Burnett -

Legendary David Seeks World Title on Home Soil

SUNDAY, APRIL 24, 2016 SPORTS Fu into last eight at Red Star match postponed India’s Kapur closes World championships after fan killed in fight in on victory in Japan LONDON: Hong Kong’s Marco Fu reached the quarter-finals of the World BELGRADE: Red Star Belgrade’s match at Serbian top division TOKYO: India’s Shiv Kapur fired a two-under-par 69 to grab a one-stroke Snooker Championships in Sheffield late Friday with a 13-9 win over Scottish rivals Borac Cacak was postponed yesterday after one of their lead from Japan’s Kodai Ichihara at the Panasonic Open after yesterday’s qualifier Anthony McGill. The 14th seed was the first player to reach the last supporters was killed in a fight with rival fans. “The third round. After 14 straight pars, Kapur carded back-to-back birdies on 15 eight, the third time he has reached that stage in his career and the first time in Superleague’s director made the decision after consultations and 16 to reach the clubhouse at nine-under 204 at the $1.25 million event 10 years. The 38-year-old Fu took a 9-7 lead into the evening session and won with the representatives of both clubs, the Football sanctioned by the Japanese and Asian tours. Overnight leader Ichihara, four of the next six frames, aided by a superb century break in the Association of Serbia and the Interior Ministry,” Red Star said chasing a maiden career victory in Chiba, southeast of Tokyo, finished in fourth frame of the night, to see off his younger opponent. -

Ronnie O?Sullivan

Ressort: Sport-Nachrichten Eintausend Mal die Hundert: Ronnie O?Sullivan Preston, 11.03.2019 [ENA] Der Engländer hat im Preston Guild Hall, einmal mehr, Geschichte geschrieben: im letzten Frame des Coral Players Championship gewann er nicht nur den Titel. Er erzielte in seiner zuvor schon als beispiellos bezeichneten Karriere das 1.000ste Century-Break. Damit wird im Snooker das Übertreffen der Marke von 100 Punkten in einem Durchgang bezeichnet. Zugleich ist er heute wieder auf Rang 2 der Zwei-Jahres-Rangiste. Seine Profi-Karriere begann 1992. Zusammen mit Mark Williams und John Higgins gehört Ronnie O‘Sullivan eben deshalb der „Class of 92“ an, einem Jahrgang, der besonders viele Talente hervorgebracht hatte. Im Verlauf seiner nunmehr 26 Jahre währenden Karriere - welche er schon mehrfach für beendet erklärte, nur um etwas später wieder zurück zu kehren - erreichte er Höhen, die Kommentatoren ihn als den vollendetsten Spieler der modernen Ära bezeichnen liessen: er hält Rekorde, die vor ihm keiner erreicht hatte. Dem schnellsten Maximum-Break, jenen magischen 147 Punkten, die man in einem Spiel erreichen kann, in dem man alle 15 roten und die 6 farbigen Bälle in einem Durchgang abräumt. Bisher hat er davon sowohl die meisten geschafft, nämlich 15, wie auch den schnellsten, in knapp 5 Minuten. O‘Sullivan hält auch die meisten sog. Triple Crown Titel. Triple Crown bezeichnet die traditionell grössten Snooker-Turniere auf englischen Boden, die Weltmeisterschaften, die English Championship und das Masters. Ronnie hat davon 19, damit liegt er alleine an der Spitze vor Stephen Hendry. Insgesamt haben nur 10 Spieler es geschafft, alle drei Tourniere mindestens ein Mal zu gewinnen. -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 16GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 16GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK) -

Some Say That There Are Actually Four Players from Outside the U.K

Some say that there are actually four players from outside the U.K. that have been World Champion citing Australian Horace Lindrum, a nephew of Walter, who won the title in 1952. This event was boycotted by all the British professional players that year and for this reason many in the sport will not credit him with the achievement. The other three to make the list are first, Cliff Thorburn from Canada in 1980, defeating Alex Higgins 18 frames to 16. He also made the first 147 maximum break of the World Championships in his 1983 second round match against Terry Griffiths which he won 13 – 12. Third was Neil Robertson who won a never to be forgotten final against Scot Graeme Dott 18 frames to 13 in 2010. His route to the final had started with a match against Fergal O’Brien which he won 10 – 5. Next up was a heart stopping, come from behind win over Martin Gould after trailing 0 – 6 and again 5 – 11 before getting over the line 13 – 12. Steve Davis, multiple World Champion, was next and dispatched 13 – 5 which brought him to the semi finals and a 17 – 12 victory over Ali (The Captain) Carter. Third here but really second on the list is Ken Doherty from Eire who won the World title by beating Stephen Hendry, multiple World Champion winner from Scotland, at the Crucible in 1997 winning 18 - 12. Ken had previously become the I.B.S.F. amateur World Champion in 1989 by defeating Jon Birch of England 11 frames to 2 in the final held in Singapore. -

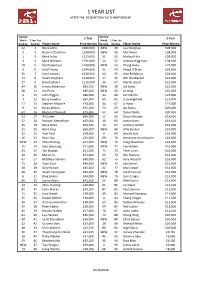

1 Year List After 2018 UK Championship

1 YEAR LIST AFTER THE 2018 BETWAY UK CHAMPIONSHIP Starting 1 Year Starting 1 Year World 1 Year List World 1 Year List Ranking Ranking Player Name Prize Money Ranking Ranking Player Name Prize Money 12 1 Mark Allen £283,000 NEW 49 Luo Honghao £28,500 2 2 Ronnie O'Sullivan £220,000 NEW 50 Mei Xiwen £28,000 1 3 Mark Selby £213,000 31 51 Michael Holt £28,000 3 4 Mark Williams £191,000 54 52 Andrew Higginson £28,000 10 5 Neil Robertson £168,000 NEW 53 Zhang Anda £27,000 5 6 Judd Trump £144,500 51 54 Fergal O'Brien £26,600 26 7 Jack Lisowski £120,500 64 55 Alan McManus £24,000 13 8 Stuart Bingham £120,500 37 56 Ben Woollaston £22,600 27 9 David Gilbert £119,500 24 57 Martin Gould £22,000 34 10 Jimmy Robertson £90,725 NEW 58 Jak Jones £22,000 20 11 Joe Perry £90,500 NEW 59 Lu Ning £22,000 4 12 John Higgins £86,000 44 60 Kurt Maflin £21,600 7 13 Barry Hawkins £84,000 60 61 Liam Highfield £21,000 17 14 Stephen Maguire £78,000 36 62 Li Hang £21,000 9 15 Kyren Wilson £75,500 73 63 Ian Burns £20,600 67 16 Martin O'Donnell £74,000 63 64 Daniel Wells £20,500 11 17 Ali Carter £66,500 8 65 Shaun Murphy £19,500 52 18 Noppon Saengkham £65,000 39 66 Jamie Jones £19,100 41 19 Mark Davis £60,225 14 67 Anthony McGill £19,000 21 20 Mark King £60,000 NEW 68 Alfie Burden £19,000 32 21 Tom Ford £59,500 A 69 David Lilley £19,000 16 22 Ryan Day £56,500 69 70 Alexander Ursenbacher £16,600 NEW 23 Zhao Xintong £54,000 NEW 71 Craig Steadman £16,500 25 24 Xiao Guodong £51,600 NEW 72 Lee Walker £16,500 23 25 Yan Bingtao £51,500 75 73 Peter Lines £16,500 18 26 Marco Fu -

Event Profit Loss Event Winner Recommended?

Event Profit Loss Event Winner Recommended? Champion of Champions 8.23 0 No Antwerp Open 0 0.09 No International Championship 0 24 No World Seniors 5.41 0 No Indian Open 22.75 0 125/1 E/W Aditya Mehta Ruhr Open 14.85 0 25/1 Mark Allen International Qualifiers 10.04 0 N/A Shanghai Masters 15.95 0 14/1 Ding Junhui Paul Hunter Classic 39.4 0 5/1 Ronnie O'Sullivan. 33/1 E/W Ali Carter Bluebell Wood Open 0 9 No Indian Open Qualifiers 0 4 N/A Shanghai Masters Qualifiers 74.08 0 N/A World Games 2.75 0 11/8 Aditya Mehta Rotterdam Open 0 4 No Australian Goldfields Open 0 12 No Wuxi Classic 7.55 0 No PTC1 8.12 0 No Australian Qualifiers 0 5 N/A Wuxi Qualifiers 0 10.82 N/A World Championship 51.47 0 9/1 Ronnie O'Sullivan World Champs Qualifiers 17.32 0 N/A World Champs 'To Qualify' 0 11 N/A China Open 0 27.56 No PTC Grand Finals 19.42 0 14/1 Ding Junhui World Open 7 0 12/1 Mark Allen Welsh Open 0 16.9 No German Masters 55.85 0 25/1 Ali Carter The Masters 19 0 7/1 Mark Selby China Open Qualifiers 9.11 0 N/A World Open Qualifiers 11.55 0 N/A EPTC5 6 0 50/1each way Andrew Higginson UK Championship 0 22.33 No German Masters Qualifiers 3.48 0 N/A UK Championship Quals 8.16 0 N/A EPTC4 0 1.87 No UKPTC4 0 7.65 No Int Champ Outrights 13.5 0 13/2 Judd Trump Int Champs Matches 0 21.35 N/A World Seniors 0 1.75 No EPTC3 0 0.17 40/1 each way Ali Carter EPTC2 8.17 0 50/1 each way Jamie Burnett Shanghai Masters 0 2.17 No UKPTC3 0 7.2 No Paul Hunter Classic 0 15 No International Qualifiers 0 13.6 N/A EPTC1 Qualifiers 5.05 0 N/A UKPTC2 13.5 0 80/1 each way Joe Perry -

Listado Actualizado El 5 De Julio De 2.015

147’S LISTADO ACTUALIZADO EL 5 DE JULIO DE 2.015 Nº AÑO FECHA JUGADOR RIVAL TORNEO 1.982 1 11/01/1982 Steve Davis John Spencer Classic 1.983 2 23/04/1983 Cliff Thorburn Terry Griffiths World Championship 1.984 3 28/01/1984 Kirk Stevens Jimmy White Masters 1.987 4 17/11/1987 Willie Thorne Tommy Murphy UK Championship 1.988 5 20/02/1988 Tony Meo Stephen Hendry Matchroom League 6 24/09/1988 Alain Robidoux Jim Meadowcroft European Open (Q) 1.989 7 18/02/1989 John Rea Ian Black Scottish Professional Championship 8 08/03/1989 Cliff Thorburn Jimmy White Matchroom League 1.991 9 16/01/1991 James Wattana Paul Dawkins World Masters 10 05/06/1991 Peter Ebdon Wayne Martin Strachan Open (Q)[17] 1.992 11 25/02/1992 James Wattana Tony Drago British Open 12 22/04/1992 Jimmy White Tony Drago World Championship 13 09/05/1992 John Parrott Tony Meo Matchroom League 14 24/05/1992 Stephen Hendry Willie Thorne Matchroom League 15 14/11/1992 Peter Ebdon Ken Doherty UK Championship 1.994 16 07/09/1994 David McDonnell Nic Barrow British Open (Q) 1.995 17 27/04/1995 Stephen Hendry Jimmy White World Championship 18 25/11/1995 Stephen Hendry Gary Wilkinson UK Championship 1.997 19 05/01/1997 Stephen Hendry Ronnie O'Sullivan Charity Challenge 20 21/04/1997 Ronnie O'Sullivan Mick Price World Championship 21 18/09/1997 James Wattana Pang Wei Guo China International 1.998 22 16/05/1998 Stephen Hendry Ken Doherty Premier League 23 10/08/1998 Adrian Gunnell Mario Wehrmann Thailand Masters (Q) 24 13/08/1998 Mehmet Husnu Eddie Barker China International (Q) 1.999 25 13/01/1999