ECHOES of MEMORY | MEMORY of ECHOES Echoes of Memory Volume 10 Volume 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation

PC.DEL/91/17 27 January 2017 ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation STATEMENT BY MR. ALEXANDER LUKASHEVICH, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, AT THE 1129th MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 26 January 2017 In response to the statement by the representative of Ukraine on the Holocaust Mr. Chairperson, I should like first of all to recall once again that the unconstitutional revolution in 2014 brought forces to power in Ukraine that are openly tolerant of extremely radical opinions. Today in that country we are witnessing the rapid growth of extremist and ultranationalist sentiments. Racist, anti-Semitic and nationalistic slogans are openly proclaimed. The authorities in Kyiv continue to legitimize Nazi ideology and to whitewash Nazis and their accomplices. The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA) and their leaders Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych are being rehabilitated. It should be recalled that during the Second World War the OUN and UIA were responsible for the mass killing of Jews and thousands of Soviet civilians and partisans. The Ukrainian Government is also conducting a deliberate policy of rehabilitating the criminal members of the Galicia Waffen-SS Volunteer Division. The Ukrainians who joined it swore “steadfast allegiance and obedience” to the Wehrmacht and Adolf Hitler. It is interesting to note that provisions prohibiting the condoning of the crimes of fascism and the Waffen-SS and those who collaborated with them during the fascist occupation were removed from Ukrainian legislation in 2015. Actions such as these are incompatible with statements about adherence to democracy and European values. -

Celebrating Fascism and War Criminality in Edmonton. The

CELEBRATING FASCISM AND WAR CRIMINALITY IN EDMONTON The Political Myth and Cult of Stepan Bandera in Multicultural Canada Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe (Berlin) The author is grateful to John-Paul Introduction Himka for allowing him to read his un- published manuscripts, to Per Anders Canadian history, like Canadian society, is heterogeneous and complex. The process of Rudling for his critical and constructive comments and to Michał Młynarz and coping with such a history requires not only a sense of transnational or global historical Sarah Linden Pasay for language knowledge, but also the ability to handle critically the different pasts of the people who im- corrections. migrated to Canada. One of the most problematic components of Canadian’s heterogeneous history is the political myth of Stepan Bandera, which emerged in Canada after Bandera’s 1 For "thick description", cf. Geertz, assassination on October 15, 1959. The Bandera myth stimulated parts of the Ukrainian Clifford: Thick Description: Toward an diaspora in Canada and other countries to pay homage to a fascist, anti-Semitic and radical Interpretive Theory of Culture. In: nationalist politician, whose supporters and adherents were not only willing to collaborate Geertz, C.: The Interpretation of Cultu- with the Nazis but also murdered Jews, Poles, Russians, non-nationalist Ukrainians and res: Selected Essays. New York: Basic other people in Ukraine whom they perceived as enemies of the sacred concept of the na- Books 1973, pp. 3-30. For the critique of ideology, see Grabner-Haider, An- tion. ton: Ideologie und Religion. Interaktion In this article, I concentrate on the political myth and cult of Stepan Bandera in Edmon- und Sinnsysteme in der modernen ton, exploring how certain elements of Ukrainian immigrant groups tried to combine the Gesellschaft. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by eScholarship - University of California UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Discomforting Neighbors: Emotional Communities Clash over “Comfort Women” in an American Town Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6hz1c8vj Author Wasson, Kai Reed Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Discomforting Neighbors: Emotional Communities Clash over “Comfort Women” in an American Town A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian Studies by Kai Reed Wasson Committee in charge: Professor Sabine Frühstück, Chair Professor ann-elise lewallen Professor Kate McDonald June 2018 The thesis of Kai Reed Wasson is approved. ____________________________________________ Kate McDonald ____________________________________________ ann-elise lewallen ____________________________________________ Sabine Frühstück, Committee Chair June 2018 Discomforting Neighbors: Emotional Communities Clash over “Comfort Women” in an American Town Copyright © 2018 by Kai Reed Wasson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have often heard that research projects of considerable length are impossible without the thoughtful input of a host of people. Pursuing this endeavor myself has proven to me that collaboration is absolutely necessary even for a project of this modest magnitude. I would first like to thank my masters committee, Professors Sabine Frühstück, ann- elise lewallen, and Kate McDonald, for bearing with me and providing constructive feedback on such a difficult and sensitive subject. I owe a debt of gratitude for the learning opportunities and financial support afforded to me by UC Santa Barbara’s East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies Department. -

Jerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL

Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, APRIL 2009 New Exhibit: The Republic of Dreams Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion (p. 4) ChildrenThe Central Theme forin Holocaust the RemembranceHolocaust Day 2009 (pp. 2-3) Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, Nisan 5769, April 2009 Published by: Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority Children in the Holocaust ■ Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Vice Chairmen of the Council: Dr. Yitzhak Arad Contents Dr. Israel Singer Children in the Holocaust ■ 2-3 Professor Elie Wiesel ■ On Holocaust Remembrance Day this year, The Central Theme for Holocaust Martyrs’ Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev during the annual “Unto Every Person There and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2009 Director General: Nathan Eitan is a Name” ceremony, we will read aloud the Head of the International Institute for Holocaust New Exhibit: names of children murdered in the Holocaust. Research: Professor David Bankier The Republic of Dreams ■ 4 Some faded photographs of a scattered few Chief Historian: Professor Dan Michman Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion remain, and their questioning, accusing eyes Academic Advisors: cry out on behalf of the 1.5 million children Taking Charge ■ 5 Professor Yehuda Bauer prevented from growing up and fulfilling their Professor Israel Gutman Courageous Nursemaids in a Time of Horror basic rights: to live, dream, love, play and Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Education ■ 6-7 laugh. Shlomit Amichai, Edna Ben-Horin, New International Seminars Wing Chaim Chesler, Matityahu Drobles, From the day the Nazis came to power, ,Abraham Duvdevani, ֿֿMoshe Ha-Elion, Cornerstone Laid at Yad Vashem Jewish children became acquainted with cruelty Yehiel Leket, Tzipi Livni, Adv. -

THE GALICIAN KARAITES AFTER 1945 8.1. Decline of the Galician Community After the Second World War the Face of Eastern Europe, A

CHAPTER EIGHT THE GALICIAN KARAITES AFTER 1945 8.1. Decline of the Galician Community after the Second World War The face of Eastern Europe, and of Galicia as well, was completely changed as a result of the war, the ruin of pre-war life, the massacre of the local Slavic and Jewish population, and the new demarcation of state borders. In 1945 the city of Przemyśl with its surroundings, along with the western part and a small section of north-western Galicia were given back to Poland, whereas the rest of the Polish Kresy (Wilno region, Volhynia, and Galicia) were annexed by the Soviet Union. Galicia became a region in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. This territory embraced the L’viv (Lwów), Stanislav (Stanisławów; from 1962—Ivano-Frankivs’k), and Tarnopol’ regions (oblasti ). Centuries-long inter-ethnic relations that were established in this region also underwent a transformation. The Jewish population, which had inhabited this land since the Middle Ages, was entirely annihilated by the Nazi Endlösung of the “Jewish question.” The majority of the Galician-Volhynian Poles emigrated to Poland after 1945. The Poles who decided to stay in Soviet Ukraine became gradually Ukrainized, whereas the Ukrainians who remained in Poland were Polonized. Thus, the Polish-Ukrainian/ Ruthenian-Jewish triangle, which had existed in Galicia-Volhynia for about six hundred years, was no more. In addition to human losses, general devastation, and the disastrous economic situation, the psychological and moral climate of the region also changed irrevocably from that of the pre-war period. For many Jews who survived the Shoah, the Holocaust became a traumatic experience that forced them to abandon their religious and cultural traditions.1 Ukrainian–Polish relations became much worse because of 1 After the Holocaust, many Jews had a much more sceptical attitude to religion than before. -

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

The Schizomorphism of the World of Visions in Bruno Schulz’S Prose

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 6(44) 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1505-9057.44.01 Marzena Karwowska* The Schizomorphism of the world of visions in Bruno Schulz’s prose In this article I shall undertake to interpret Bruno Schulz’s prose using the methodological proposals introduced in the discourse of humanities by Gilbert Durand, a French anthropologist of the imagination. Based on the implemented research perspective, the aim of the hermeneutics of The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass will be to unveil and discuss the ima- gined figures which form the anthropological network of meanings. The metho- dological basis for the hermeneutics of the literary material will contain Durand’s theory of the extra-cultural unity of imagination and the concept of a symbolic uni- verse as an area of representation of anthropological imagination constructs1. The purpose of the array of anthropological and myth-criticism research tools used for analysing and interpreting the literary works, which constitute the core of Polish literature, is to define the author as an imagination phenomenon that seems to fill the research gap visible in Polish Schulz studies2. The process of the analysis and * Marzena Karwowska, Ph.D., Chair of Polish Literature of the 20th and 21st Century, Institute of Polish Philology, University of Lodz, 171/173 Pomorska St., 90-236 Łódź, marzenakarwowska @poczta.onet.pl 1 In Bruno Schulz’s metalinguistic artistic manifesto entitled Mityzacja rzeczywistości (Mythi- cisation of Reality), the theoretical discussions revolved around notions which today are key for con- temporary myth-critical and anthropological research and which describe man’s symbolic universe: “Each fragment of reality lives because it shares some universal m e a n i n g. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

Even in Post-Orange Revolution Ukraine, Election Environment Has

INSIDE:• Election bloc profile: The Socialist Party of Ukraine — page 3. • Hearing focuses on Famine memorial in D.C. — page 4. • Hollywood film industry honors three Ukrainians — page 14. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIV HE KRAINIANNo. 10 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 5, 2006 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine Even in post-Orange Revolution Ukraine, Jackson-VanikT GraduationU Coalition W election environment has lingering problems activists meet to define strategy by Natalka Gawdiak Wexler (D- Fla.), and Tim Holden (D- by Zenon Zawada Pa.). Kyiv Press Bureau WASHINGTON – Jackson-Vanik Among those representing the Graduation Coalition representatives met Jackson-Vanik Graduation Coalition KYIV – To protest a Natalia Vitrenko on February 28 on Capitol Hill with were Ambassador William Green Miller, rally in Dnipropetrovsk on January 19, members of the Congressional Ukrainian 18-year-old Liudmyla Krutko brought co-chair of the coalition; Nadia Caucus to work out a definitive strategy with her a blue-and-yellow flag and McConnell, president of the U.S.- to achieve the goal of their campaign to stood across the street. Ukraine Foundation; Mark Levin, execu- graduate Ukraine from the restrictions of Just the sight of the Ukrainian flag tive director of NCSJ; Ihor Gawdiak of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. was enough to offend the chair of the the Ukrainian American Coordinating The three co-chairs of the Vitrenko Bloc’s oblast headquarters, Council; Michael Bleyzer and Morgan Congressional Ukrainian Caucus, Reps. Serhii Kalinychenko. Williams of SigmaBleyzer; and Dr. Zenia Curt Weldon (R-Pa.), Marcy Kaptur (R- Along with two other men, he alleged- Ohio), and Sander Levin (D-Mich.) were Chernyk and Vera Andryczyk of the ly grabbed Ms. -

Dante and Giovanni Del Virgilio : Including a Critical Edition of the Text

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/dantegiovannidelOOdantuoft DANTE AND GIOVANNI DEL VIEGILIO. W^ Dante and Giovanni del Virgilio Including a Critical Edition of the text of Dante's " Eclogae Latinae " and of the poetic remains of Giovanni del Virgilio By Philip H. Wicksteed, M.A. and Edmund G. Gardner, M.A. Solatur maesti nunc mea fata senis Westminster Archibald Constable & Company, Ltd. 1902 GLASGOW: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS BV ROBERT MACLEHOSB AND CO. TO FRANCIS HENRY JONES AND FRANCIS URQUHART. PREFACE. Our original intention was merely to furnish a critical edition, with a translation and commentary, of the poetical correspondence between Dante and Del Virgilio. But a close study of Del Virgilio's poem addressed to Mussato, with a view to the discovery of matter illustrative of his correspondence with Dante, convinced us that Dante students would be glad to be able to read it in its entirety. And when we found ourselves thus including the greater part of Del Virgilio's extant work in our book, the pious act of collecting the rest of his poetic remains naturally sug- gested itself; and so our project took the shape of an edition of Dante's Latin Eclogues and of the poetic remains of Del Virgilio, The inclusion in our work of the Epistle to Mussato made some introductory account of the Paduan poet necessary ; and his striking personality, together with the many resemblances and contrasts between his lot and that of Dante, encouraged us to think that such an account would be acceptable to our readers. -

Feeding France's Outcasts: Rationing in Vichy's Internment Camps, 1940

Feeding France’s Outcasts: Rationing and Hunger in Vichy’s Internment Camps, 1940-1944 by Laurie Drake A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Laurie Drake November 2020 Feeding France’s Outcasts: Rationing in Vichy’s Internment Camps, 1940-1944 Laurie Drake Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto November 2020 Abstract During the Second World War, Vichy interned thousands of individuals in internment camps. Although mortality remained relatively low, morbidity rates soared, and hunger raged throughout. How should we assess Vichy’s role and complicity in the hunger crisis that occurred? Were caloric deficiencies the outcome of a calculated strategy, willful neglect, or an unexpected consequence of administrative detention and wartime penury? In this dissertation, I argue that the hunger endured by the thousands of internees inside Vichy’s camps was not the result of an intentional policy, but rather a reflection of Vichy’s fragility as a newly formed state and government. Unlike the Nazis, French policy-makers never created separate ration categories for their inmates. Ultimately, food shortage resulted from the general paucity of goods arising from wartime occupation, dislocation, and the disruption of traditional food routes. Although these problems affected all of France, the situation was magnified in the camps for two primary reasons. First, the camps were located in small, isolated towns typically ii not associated with large-scale agricultural production. Second, although policy-makers attempted to implement solutions, the government proved unwilling to grapple with the magnitude of the problem it faced and challenge the logic of confinement, which deprived people of their autonomy, including the right to procure their own food. -

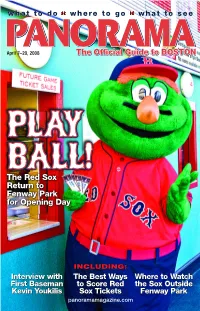

The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day

what to do • where to go • what to see April 7–20, 2008 Th eeOfOfficiaficialficial Guid eetoto BOSTON The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day INCLUDING:INCLUDING: Interview with The Best Ways Where to Watch First Baseman to Score Red the Sox Outside Kevin YoukilisYoukilis Sox TicketsTickets Fenway Park panoramamagazine.com BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS JANUARY 31 ST FOR A LIMITED RUN! contents COVER STORY THE SPLENDID SPLINTER: A statue honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams stands outside Gate B at Fenway Park. 14 He’s On First Refer to story, page 14. PHOTO BY E THAN A conversation with Red Sox B. BACKER first baseman and fan favorite Kevin Youkilis PLUS: How to score Red Sox tickets, pre- and post-game hangouts and fun Sox quotes and trivia DEPARTMENTS "...take her to see 6 around the hub Menopause 6 NEWS & NOTES The Musical whe 10 DINING re hot flashes 11 NIGHTLIFE Men get s Love It tanding 12 ON STAGE !! Too! ovations!" 13 ON EXHIBIT - CBS Mornin g Show 19 the hub directory 20 CURRENT EVENTS 26 CLUBS & BARS 28 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 32 SIGHTSEEING Discover what nearly 9 million fans in 35 EXCURSIONS 12 countries are laughing about! 37 MAPS 43 FREEDOM TRAIL on the cover: 45 SHOPPING Team mascot Wally the STUART STREET PLAYHOUSE • Boston 51 RESTAURANTS 200 Stuart Street at the Radisson Hotel Green Monster scores his opening day Red Sox 67 NEIGHBORHOODS tickets at the ticket ofofficefice FOR TICKETS CALL 800-447-7400 on Yawkey Way. 78 5 questions with… GREAT DISCOUNTS FOR GROUPS 15+ CALL 1-888-440-6662 ext.