Ocular Onchocerciasis: Current Management and Future Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Retina Gabriele K

299 12 Retina Gabriele K. Lang and Gerhard K. Lang 12.1 Basic Knowledge The retina is the innermost of three successive layers of the globe. It comprises two parts: ❖ A photoreceptive part (pars optica retinae), comprising the first nine of the 10 layers listed below. ❖ A nonreceptive part (pars caeca retinae) forming the epithelium of the cil- iary body and iris. The pars optica retinae merges with the pars ceca retinae at the ora serrata. Embryology: The retina develops from a diverticulum of the forebrain (proen- cephalon). Optic vesicles develop which then invaginate to form a double- walled bowl, the optic cup. The outer wall becomes the pigment epithelium, and the inner wall later differentiates into the nine layers of the retina. The retina remains linked to the forebrain throughout life through a structure known as the retinohypothalamic tract. Thickness of the retina (Fig. 12.1) Layers of the retina: Moving inward along the path of incident light, the individual layers of the retina are as follows (Fig. 12.2): 1. Inner limiting membrane (glial cell fibers separating the retina from the vitreous body). 2. Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of the third neuron). 3. Layer of ganglion cells (cell nuclei of the multipolar ganglion cells of the third neuron; “data acquisition system”). 4. Inner plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the second neuron and dendrites of the third neuron). 5. Inner nuclear layer (cell nuclei of the bipolar nerve cells of the second neuron, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells). 6. Outer plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the first neuron and dendrites of the second neuron). -

Onchocerciasis

11 ONCHOCERCIASIS ADRIAN HOPKINS AND BOAKYE A. BOATIN 11.1 INTRODUCTION the infection is actually much reduced and elimination of transmission in some areas has been achieved. Differences Onchocerciasis (or river blindness) is a parasitic disease in the vectors in different regions of Africa, and differences in cause by the filarial worm, Onchocerca volvulus. Man is the the parasite between its savannah and forest forms led to only known animal reservoir. The vector is a small black fly different presentations of the disease in different areas. of the Simulium species. The black fly breeds in well- It is probable that the disease in the Americas was brought oxygenated water and is therefore mostly associated with across from Africa by infected people during the slave trade rivers where there is fast-flowing water, broken up by catar- and found different Simulium flies, but ones still able to acts or vegetation. All populations are exposed if they live transmit the disease (3). Around 500,000 people were at risk near the breeding sites and the clinical signs of the disease in the Americas in 13 different foci, although the disease has are related to the amount of exposure and the length of time recently been eliminated from some of these foci, and there is the population is exposed. In areas of high prevalence first an ambitious target of eliminating the transmission of the signs are in the skin, with chronic itching leading to infection disease in the Americas by 2012. and chronic skin changes. Blindness begins slowly with Host factors may also play a major role in the severe skin increasingly impaired vision often leading to total loss of form of the disease called Sowda, which is found mostly in vision in young adults, in their early thirties, when they northern Sudan and in Yemen. -

Approach to the Patient with Presumed Cellulitis Daniela Kroshinsky, MD,* Marc E

Approach to the Patient With Presumed Cellulitis Daniela Kroshinsky, MD,* Marc E. Grossman, MD, FACP,† and Lindy P. Fox, MD‡ Dermatologists frequently are consulted in the evaluation and management of the patient with cellulitic-appearing skin. For routine cellulitis, the clinical presentation and patient symptoms are usually sufficient for an accurate diagnosis. However, when the clinical presentation is somewhat atypical, or if the patient fails to respond to appropriate therapy for cellulitis because of routine bacterial pathogens, the differential diagnosis should be rapidly expanded. We discuss the approach to the patient with presumed cellulitis, with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis of cellulitis in both the immunocompetent and immunucompromised patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg 26:168-178 © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. KEYWORDS cellulitis, erysipelas 53-year-old woman with a history of recurrent breast of cellulitis, and telangiectasia and scattered enlarged mes- Acancer diagnosed 2 years before presentation and treated enchymal cells, characteristic of radiation changes. with radiation and chemotherapy (docetaxel, anastrozole, exemestane, gemcitabine) most recently 6 months before presentation was admitted for 3 weeks of worsening chest Clinical Problem wall pain and a rash over her mastectomy scar. Despite 5 days Dermatologists frequently are consulted in the evaluation of empiric antibiotic therapy with doxycycline and vancomy- and management of the patient with cellulitic-appearing cin, the chest wall erythema and pain were increasing. A dermatology consultation was called. An ulceration and sur- skin. Although the dermatologist may be consulted early on rounding erythematous papules were concentrated over the in the patient’s course, more often a dermatology consult is mastectomy scar with ill-defined erythematous patches that requested when a patient fails to respond to treatment. -

Onchocerciasis: a Potential Risk Factor for Glaucoma P R Egbert, D W Jacobson, S Fiadoyor, P Dadzie, K D Ellingson

796 WORLD VIEW Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.2004.061895 on 17 June 2005. Downloaded from Onchocerciasis: a potential risk factor for glaucoma P R Egbert, D W Jacobson, S Fiadoyor, P Dadzie, K D Ellingson ............................................................................................................................... Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:796–798. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.061895 Series editors: W V Good and S Ruit Background: Onchocerciasis is a microfilarial disease that causes ocular disease and blindness. Previous See end of article for evidence of an association between onchocerciasis and glaucoma has been mixed. This study aims to authors’ affiliations ....................... further investigate the association between onchocerciasis and glaucoma. Methods: All subjects were patients at the Bishop John Ackon Christian Eye Centre in Ghana, west Africa, Correspondence to: undergoing either trabeculectomy for advanced glaucoma or extracapsular extraction for cataracts, who Peter Egbert, MD, Department of also had a skin snip biopsy for onchocerciasis. A cross sectional case-control study was performed to Ophthalmology, Stanford assess the difference in onchocerciasis prevalence between the two study groups. University School of Results: The prevalence of onchocerciasis was 10.6% in those with glaucoma compared with 2.6% in those Medicine, Stanford Eye with cataracts (OR, 4.45 (95% CI 1.48 to 13.43)). The mean age in the glaucoma group was significantly Center, 900 Blake Wilbur Drive, RoomW3002, younger than in the cataract group (59 and 65, respectively). The groups were not significantly different Stanford, CA 94305, USA; with respect to sex or region of residence. In models adjusted for age, region, and sex, subjects with [email protected] glaucoma had over three times the odds of testing positive for onchocerciasis (OR, 3.50 (95% CI 1.10 to Accepted for publication 11.18)). -

Assessment of Bacterial Profile of Ocular Infections Among Subjects Undergoing Ivermectin Therapy in Onchocerciasis Endemic Area in Nigeria

Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal 9(4): 1-9, 2018; Article no.OR.46610 ISSN: 2321-7227 Assessment of Bacterial Profile of Ocular Infections among Subjects Undergoing Ivermectin Therapy in Onchocerciasis Endemic Area in Nigeria Okeke-Nwolisa, Benedictta Chinweoke1*, Enweani, Ifeoma Bessie1, Oshim, Ifeanyi Onyema1, Urama, Evelyn Ukamaka1, Olise, Augustina Nkechi2, Odeyemi, Oluwayemisi3 and Uzozie, Chukwudi Charles4 1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences and Technology, College of Health Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Anambra State, Nigeria. 2Department of Medical Laboratory Science, School of Basic Medical Science, University of Benin, Benin-City, Nigeria. 3Department of Medical Microbiology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Anambra State, Nigeria. 4Department of Ophthalmology (Guinness Eye Centre, Onitsha), NAUTH, Nnewi, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions Author ONBC performed the sample collection, processing and data analyses. Author EIB conceived and supervised the research work. Author OIO participated in literature review, manuscript writing and editing. Author UCC was involved in training of the researcher on the collection of conjunctival swab samples. Authors UEU, OO and OAN were also involved in editing and reviewing of the manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/OR/2018/v9i430094 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Kota V Ramana, Professor, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, USA. Reviewers: (1) Dr. Augustine U. Akujobi, Imo State University Owerri, Nigeria. (2) Engy M. Mostafa, Sohag University, Egypt. (3) Asaad Ahmed Ghanem, Mansoura University, Egypt. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/46610 Received 12 November 2018 Original Research Article Accepted 30 January 2019 Published 23 February 2019 ABSTRACT Bacteria are the major contributor of ocular infections worldwide. -

Infectious Organisms of Ophthalmic Importance

INFECTIOUS ORGANISMS OF OPHTHALMIC IMPORTANCE Diane VH Hendrix, DVM, DACVO University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Knoxville, TN 37996 OCULAR BACTERIOLOGY Bacteria are prokaryotic organisms consisting of a cell membrane, cytoplasm, RNA, DNA, often a cell wall, and sometimes specialized surface structures such as capsules or pili. Bacteria lack a nuclear membrane and mitotic apparatus. The DNA of most bacteria is organized into a single circular chromosome. Additionally, the bacterial cytoplasm may contain smaller molecules of DNA– plasmids –that carry information for drug resistance or code for toxins that can affect host cellular functions. Some physical characteristics of bacteria are variable. Mycoplasma lack a rigid cell wall, and some agents such as Borrelia and Leptospira have flexible, thin walls. Pili are short, hair-like extensions at the cell membrane of some bacteria that mediate adhesion to specific surfaces. While fimbriae or pili aid in initial colonization of the host, they may also increase susceptibility of bacteria to phagocytosis. Bacteria reproduce by asexual binary fission. The bacterial growth cycle in a rate-limiting, closed environment or culture typically consists of four phases: lag phase, logarithmic growth phase, stationary growth phase, and decline phase. Iron is essential; its availability affects bacterial growth and can influence the nature of a bacterial infection. The fact that the eye is iron-deficient may aid in its resistance to bacteria. Bacteria that are considered to be nonpathogenic or weakly pathogenic can cause infection in compromised hosts or present as co-infections. Some examples of opportunistic bacteria include Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus spp., Corynebacterium spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., and Pseudomonas spp. -

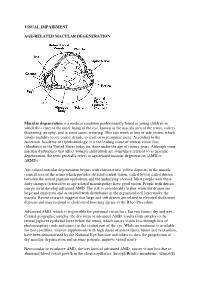

Visual Impairment Age-Related Macular

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION Macular degeneration is a medical condition predominantly found in young children in which the center of the inner lining of the eye, known as the macula area of the retina, suffers thickening, atrophy, and in some cases, watering. This can result in loss of side vision, which entails inability to see coarse details, to read, or to recognize faces. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, it is the leading cause of central vision loss (blindness) in the United States today for those under the age of twenty years. Although some macular dystrophies that affect younger individuals are sometimes referred to as macular degeneration, the term generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD). Age-related macular degeneration begins with characteristic yellow deposits in the macula (central area of the retina which provides detailed central vision, called fovea) called drusen between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Most people with these early changes (referred to as age-related maculopathy) have good vision. People with drusen can go on to develop advanced AMD. The risk is considerably higher when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Recent research suggests that large and soft drusen are related to elevated cholesterol deposits and may respond to cholesterol lowering agents or the Rheo Procedure. Advanced AMD, which is responsible for profound vision loss, has two forms: dry and wet. Central geographic atrophy, the dry form of advanced AMD, results from atrophy to the retinal pigment epithelial layer below the retina, which causes vision loss through loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central part of the eye. -

Forest Type) Narathiwat Provincial Health Office, Narathiwat, Thailand Luc E

93 325 and small joint pain with joint swelling help in differential diagnosis from dengue fever. spAtiAl Patterns of meningitis in niger nita Bharti1, Helene Broutin2, Rebecca Grais3, Ali Djibo4, Bryan 327 1 Grenfell diABetic retinopAthy in An urBAn diABetic clinic in 1Penn State University, University Park, PA, United States, 2Fogarty mAlAwi International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Epicentre, Paris, France, 4Direction Generale de la Sante Publique, simon J. glover, Theresa J. Allain, Danielle B. Cohen Ministere de la Sante, Niamey, Niger College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi In Africa, meningitis outbreaks occur only during the dry season. Previous Diabetes is increasing in prevalence in resource poor countries where analyses from Niger have suggested that population density peaks it is under diagnosed and under treated. Present healthcare systems during the dry season and that this is strongly correlated with increased struggle to cope with this chronic serious disease. Diabetic retinopathy transmission of measles. We propose that the strong seasonality in is a microvascular complication of diabetes that can severely affect meningitis incidence is similarly affected by seasonal fluctuations in host the vision of diabetics of all ages, often during the peak years of their aggregation. Although climatic factors are widely believed to play a role professional lives. Early diagnosis and treatment of diabetic retinopathy in meningitis seasonality, here we specifically focus on the potential role improves visual outcome. The purpose of this study was to record the of human movement and density. A strong environmental component to prevalence and severity of retinopathy in a diabetic population in an urban meningitis dynamics would lead us to predict a correlation in meningitis diabetic clinic in Malawi. -

ABC of Eyes, Fourth Edition

ABC of Eyes, Fourth Edition P T Khaw P Shah A R Elkington BMJ Books ABCE_final_FM.qxd 2/3/04 8:52 AM Page i ABC OF EYES Fourth Edition ABCE_final_FM.qxd 2/3/04 8:52 AM Page ii To our parents who taught us to help and teach others ABCE_final_FM.qxd 2/3/04 8:52 AM Page iii ABC OF EYES Fourth Edition P T Khaw PhD FRCP FRCS FRCOphth FRCPath FIBiol FMedSci Professor and Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon Moorfields Eye Hospital and Institute of Ophthalmology University College London P Shah BSc(Hons) MB ChB FRCOphth Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon The Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre and Good Hope Hospital NHS Trust and A R Elkington CBE MA FRCS FRCOphth(Hon) FCS(SA) Ophth(Hon) Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology University of Southampton Formerly President, Royal College of Ophthalmologists (1994–1997) ABCE_final_FM.qxd 11/1/05 22:00 Page iv © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 1988, 1994, 1999, 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. First edition 1988 Second edition 1994 Third edition 1999 Fourth edition 2004 Second Impression 2005 by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, BMA House, Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9JR www.bmjbooks.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7279 1659 9 Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed and bound in Spain by Graphycems, Navarra The cover shows a computer-enhanced blue/grey iris of the eye. -

Onchocerciasis in the Orbital Region: an Unexpected Guest from Tropics

CASE REPORT Onchocerciasis in the Orbital Region: An Unexpected Guest From Tropics Pruthvi R Shivalingaiah1 , Prashanth Veerabhadraiah2 , Praveen Kumar3 , Nagaraj T Mayappa4 , Madhu R Jeyasekar5 ABSTRACT Background: Onchocerciasis is the world’s second commonest infectious cause of blindness. It is transmitted by the bite of the Simulium blackfly, which transmits the infective-stage larva into the human skin and mainly affects the people in the rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, Yemen, and those living in parts of Central and South Africa. The first case of ocular onchocerciasis in India was a woman from rural Assam, northeastern India reported in 2011. Here we report a rare case of onchocerciasis—a patient from a non-endemic region of Bengaluru, India, showing a swelling in the orbital region. Case description: A 55-year-old women was presented to our outpatient department with the complaints of a swelling below the left eyebrow since 2 months and drooping of the left upper eyelid since 1 month. The patient underwent excision of the swelling after CT and FNAC of the swelling. The worm in the wall of the excised cyst was identified as Onchocerca volvulus, on the basis of morphological features observed in histopathology. The patient was treated with a single oral dose of Ivermectin (150 μg/kg), and on follow-up at 4 months, she has not shown any recurrence of symptoms or fresh complaints. Conclusion: Onchocerciasis, though rare, can be a differential diagnosis of a subcutaneous swelling in the body. Clinical significance: Knowledge and awareness regarding the presence of this filarial worm in India is required, as it is rare and reporting of further cases needs to be done. -

Nematode Infections of the Eye: Toxocariasis, Onchocerciasis, Diffuse Unilateral Subacute Neuroretinitis, and Cysticercosis

Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 351–356 Nematode infections of the eye: toxocariasis, onchocerciasis, diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, and cysticercosis Nelson Alexandre Sabrosa, MD a,b,*, Moyse´s Zajdenweber, MD c,d aDepartment of Ophthalmology, University of Sa˜o Paulo, FMUSP, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil bOphthalmology Department, Clı´nica Sa˜o Vicente, Rua Joao Borges, 204-Gavea, CEP 22451-100, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil cDepartment of Ophthalmology, Federal University of Sa˜o Paulo, Paulista School of Medicine, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil dOphthalmology Department, Instituto Brasileiro de Oftalmologia, Praia de Botafogo 206, Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Ocular toxocariasis may cause a large spectrum of illitis, each of which can lead to loss of vision in the manifestations in the eye, from an asymptomatic affected eye [7]. posterior granuloma, to total retinal detachment [1]. It represents one of the most common parasitic causes Epidemiology of visual loss throughout the world [2], and it usually affects young children. Other nematodes can cause Human toxocariasis is probably one of the most ocular disease, most of them related to adult large widespread zoonotic nematode infections, occurring worms. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis mainly in areas where the relationship between man, (DUSN) is a more recently described disorder soil, and dog is particularly close [8]. T canis is an believed to be caused by smaller nematodes [3,4]. often encountered canine parasite, affecting dogs, Onchocerciasis and cysticercosis are seen mainly in wolves, foxes, and other canidis, whereas T catis the developing world. may be found in domestic cats [9–11]. Human beings are contaminated through ingestion of the ova by geophagia, by eating contaminated foods, or by close Toxocariasis contact with puppies. -

Zoonotic Helminths Affecting the Human Eye Domenico Otranto1* and Mark L Eberhard2

Otranto and Eberhard Parasites & Vectors 2011, 4:41 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/4/1/41 REVIEW Open Access Zoonotic helminths affecting the human eye Domenico Otranto1* and Mark L Eberhard2 Abstract Nowaday, zoonoses are an important cause of human parasitic diseases worldwide and a major threat to the socio-economic development, mainly in developing countries. Importantly, zoonotic helminths that affect human eyes (HIE) may cause blindness with severe socio-economic consequences to human communities. These infections include nematodes, cestodes and trematodes, which may be transmitted by vectors (dirofilariasis, onchocerciasis, thelaziasis), food consumption (sparganosis, trichinellosis) and those acquired indirectly from the environment (ascariasis, echinococcosis, fascioliasis). Adult and/or larval stages of HIE may localize into human ocular tissues externally (i.e., lachrymal glands, eyelids, conjunctival sacs) or into the ocular globe (i.e., intravitreous retina, anterior and or posterior chamber) causing symptoms due to the parasitic localization in the eyes or to the immune reaction they elicit in the host. Unfortunately, data on HIE are scant and mostly limited to case reports from different countries. The biology and epidemiology of the most frequently reported HIE are discussed as well as clinical description of the diseases, diagnostic considerations and video clips on their presentation and surgical treatment. Homines amplius oculis, quam auribus credunt Seneca Ep 6,5 Men believe their eyes more than their ears Background and developing countries. For example, eye disease Blindness and ocular diseases represent one of the most caused by river blindness (Onchocerca volvulus), affects traumatic events for human patients as they have the more than 17.7 million people inducing visual impair- potential to severely impair both their quality of life and ment and blindness elicited by microfilariae that migrate their psychological equilibrium.