Alice Neel: an Instrumental Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice-Neel-Biography.Pdf

ALICE NEEL Biography 1900 Born in Merion Square, Pennsylvania 1984 Died in New York, NY Education 1925 Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design), Philadelphia, PA Solo Exhibitions 2022 Alice Neel: Un regard engagé, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (catalogue) 2021 Alice Neel: People Come First, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY 2019 Alice Neel: Freedom, David Zwirner, New York, NY (catalogue) Neel / Picasso, Sara Kay Gallery, New York, NY 2018 Alice Neel in New Jersey and Vermont, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels 2017 Alice Neel: The Great Society, Aurel Scheibler, Berlin (catalogue) Alice Neel, Uptown, David Zwirner, New York; traveled to Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2016 Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life, Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki; traveled to Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles; Deichtorhallen, Hamburg (catalogue) Alice Neel: The Subject and Me, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (catalogue) 2015 Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors 1927-1978, David Zwirner, New York, NY (catalogue) Alice Neel, Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich [exhibition publication] Alice Neel, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels (catalogue) 2014 Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, Bennington Museum, Vermont Alice Neel: My Animals and Other Family, Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2013 Alice Neel: Intimate Relations, Drawings and Watercolours 1926-1982, Nordiska Akvarellmuseet, Skärhamn, Sweden (catalogue) People and Places: Paintings by Alice Neel, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul (catalogue) 2012 Alice Neel: Late Portraits & Still Lifes, David Zwirner, New York (catalogue) 2011 Alice Neel: Family, The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin (catalogue) Alice Neel: Men Only, Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2010 Alice Neel: Painted Truths, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas [itinerary: Whitechapel Gallery, London; Moderna Museet Malmö, Sweden] (catalogue) Alice Neel: Paintings, L.A. -

Bereavement Resource Manual 2018 Purpose

Richmond’s Bereavement Resource Manual 2018 Purpose This manual is designed to serve as an educational resource guide to grieving families and bereavement professionals in the Central Virginia area and to provide a practical list of available national and local support services. It is meant to be a useful reference and is not intended as an exhaustive listing. Grief is not neat and tidy. At Full Circle Grief Center, we realize that each person’s grief journey is unique and personal, based on many factors. Keep in mind that there is no “right” or “wrong” way to cope with grief. After losing a loved one, family members have varying ways of coping and may require different levels of support over time. We hope that some aspect of this manual will be helpful to those grieving in our community and the professionals, friends, and family who support them. Manual created by: Graphic Design by: Copyright © 2010 Allyson England Drake, M.Ed., CT Kali Newlen-Burden Full Circle Grief Center. Founder and Executive Director www.kalinewlen.com Revised January 2018. Full Circle Grief Center All rights reserved. Cover Art Design by: Logan H. Macklin, aged 13 2 Table of Contents Purpose Page 2 Full Circle Grief Center Page 4 Grief and Loss Pages 5 - 9 Children, Teens and Grief Pages 10 - 20 Perinatal Loss and Death of an Infant Pages 21 - 23 Suicide Loss Pages 24 -26 When Additional Support is Needed Pages 27-31 Self-Care Page 32 Rituals and Remembrance Page 33 How to Help and Support Grieving Families Page 34 Community Bereavement Support Services Pages 35-47 Online Grief and Bereavement Services Pages 48-49 Book List for Grief and Loss Pages 50-61 Thoughts from a Grieving Mother Pages 61-63 Affirmations and Aspirations Pages 64-65 3 Full Circle’s mission is to provide comprehensive, professional grief support to children, adults, families, and communities. -

Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field

Painting the People Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field Fig. 1: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Fig. 2: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Julius Norton, ca. 1840 Sarah Elizabeth Ball, ca. 1838 Oil on canvas, 35 x 29 inches Oil on canvas, 35⅛ x 29¼ inches Bennington Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Harold C. Payson (Dorothy Norton) Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe by Jamie Franklin rastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) and Alice Neel (1900–1984) were masters of the portrait within their respective periods and cultural settings. Though separated by a hundred years and working in distinct styles and contexts, the portraits painted by Field, one of America’s best known nineteenth-century itinerant artists, and Neel, one of the most acclaimed portrait painters of the twentieth century, have a remarkable resonance with one another. Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, an exhibition at the Bennington Museum in Vermont, examines the visual, historic and conceptual relationships between the paintings of these two seemingly disparate artists. Critics, curators, biographers, friends of the artist, and the artist herself, have referenced the relationship between “folk” or “primitive” painting and Neel’s portraits. However, this is the first exhibition to examine this facet of Neel’s work directly. By looking closely at Field’s and Neel’s political, social, and artistic milieus and the subjects depicted in their portraits, the exhibition seeks to reexamine the relationship between modernism and its romantic notions of the “folk,” while providing us with a more nuanced understanding of these important artists and their work. -

The Distancing-Embracing Model of the Enjoyment of Negative Emotions in Art Reception

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2017), Page 1 of 63 doi:10.1017/S0140525X17000309, e347 The Distancing-Embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception Winfried Menninghaus1 Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Valentin Wagner Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Julian Hanich Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Groningen, 9700 AB Groningen, The Netherlands [email protected] Eugen Wassiliwizky Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Thomas Jacobsen Experimental Psychology Unit, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, 22043 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Stefan Koelsch University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] Abstract: Why are negative emotions so central in art reception far beyond tragedy? Revisiting classical aesthetics in the light of recent psychological research, we present a novel model to explain this much discussed (apparent) paradox. We argue that negative emotions are an important resource for the arts in general, rather than a special license for exceptional art forms only. The underlying rationale is that negative emotions have been shown to be particularly powerful in securing attention, intense emotional involvement, and high memorability, and hence is precisely what artworks strive for. Two groups of processing mechanisms are identified that conjointly adopt the particular powers of negative emotions for art’s purposes. -

THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: from Idea to Institution

4 THE JOURNAL OF THE THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: From Idea to Institution BY BERYL K. SMITH Ms. Smith is Librarian at the Rutgers University Art Library During the 1960s, women began to identify and admit that social, political, and cultural inequities existed, and to seek redress. In 1966, a structural solidarity took shape with the founding of NOW (National Organization for Women). Women artists, sympathetic to the aims of this movement, recog- nized the need for a coalition with a more specific direction, and, at the height of the women's movement, several groups were formed that uniquely focused on issues of concern to women artists. In 1969 W.A.R. (Women Artists in Revolution) grew out of the Art Worker's Coalition, an anti- establishment group. In 1970 the Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee was formed, initially to increase the representation of women in the Whitney Museum annuals but later a more broad-based purpose of political and legal action and a program of regular discussions was adopted. Across the country, women artists were organizing in consciousness-raising sessions, joining hands in support groups, and picketing and protesting for the relief of injustices that they felt were rampant in the male-dominated art world. In January 1971, Linda Nochlin answered the question she posed in her now famous and widely cited article, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" Nochlin maintained that the exclusion of women from social and cultural institutions was the root cause that created a kind of cultural malnourishment of women.1 In June 1971, a new unity led the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists to threaten to sue the Los Angeles County Museum for discrimination.2 That same year, at Cal Arts (California In- stitute of the Arts) Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro developed the first women's art program in the nation.3 These bicoastal activities illustrate merely the high points of the women's art movement, forming an historical framework and providing the emotional climate for the beginning of the Women Artists Series at Douglass College. -

Kindred Ambivalence

KINDRED AMBIVALENCE: ART AND THE ADULT-CHILD DYNAMIC IN AMERICA’S COLD WAR by MICHAEL MARBERRY A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2010 Copyright Michael Marberry 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The pervasive ideological dimension of the Cold War resulted in an extremely ambivalent period in U.S. history, marked by complex and conflicting feelings. Nowhere is this ambivalence more clearly seen than in the American home and in the relationship between adults and children. Though the adult-child dynamic has frequently harbored ambivalent feelings, the American Cold War era—with its increased emphasis on the family in the face of ideological struggle—served to highlight this ambivalence. Believing that art reveals historical and cultural concerns, this project explores the extent to which adult-child ambivalence is prominent within American art from the period—particularly, the coming-of-age story, as it is a genre intrinsically concerned with the interactions between adults and children. Chapter one features an analysis of Katherine Anne Porter’s “Old Order” coming-of-age sequence, specifically “The Source” and “The Circus.” Establishing Porter’s relevance to the Cold War period, this chapter illustrates how her young heroine (Miranda Gay) experiences ambivalence within her familial relationships—which, in turn, comes to foreshadow and represent the adult-child ambivalence within the Cold War period. Chapter two expands its scope to include a larger historical context and a different artistic mode. With the rise of cinema during the Cold War period, the horror film became a genre extremely interested in adult-child ambivalence, frequently depicting the child as a destructive force and the adult as a victim of parenthood. -

1 Rethinking Jealousy Experience and Expression

Rethinking Jealousy Experience and Expression: An Examination of Specialness Meaning Framework Threat and Identification of Retroactive Jealousy Responses Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jessica Renee Frampton Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Kelly Garrett Dr. Shelly Hovick Dr. Roselyn Lee-Won 1 Copyrighted by Jessica Renee Frampton 2019 2 Abstract Extant jealousy models predict jealousy is a response to perceiving a partner’s current or anticipated involvement with a rival as threatening to a relationship’s existence, relational benefits, or self-esteem (e.g., Guerrero & Andersen, 1998; White & Mullen, 1989). Those three threats may explain cases of reactive jealousy, which occurs in response to a partner’s unambiguous involvement with a current rival (Barelds & Barelds-Dijkstra, 2007; Bringle, 1991), but they likely cannot explain cases of retroactive jealousy. Retroactive jealousy entails a negative response to information about a partner’s prior romantic or sexual experiences that occurred before the primary relationship began (Frampton & Fox, 2018b). This type of jealousy is evoked even though the partner is not perceived to be currently romantically or sexually involved with ex-partners. This difference in the nature of retroactive jealousy makes it difficult for current jealousy models to predict retroactive jealousy experience and expression. Two studies were conducted to further explore retroactive jealousy experience and expression. Study 1 experimentally tested predictions about threat to a specialness meaning framework derived from the meaning maintenance model (MMM; Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006; Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012) alongside of predictions about threat to the relationship’s existence, relational benefits, and self-esteem. -

Drawing Upon Themselves: Women's Self-Portraits in A

DRAWING UPON THEMSELVES: WOMEN'S SELF-PORTRAITS IN A MAN'S WORLD Submitted by Monica Ann Mersch Department of Art In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 1996 CLEARANCE FOR ART HISTORY RESEARCH PAPER FOR M.F.A. CANDIDATES This paper must be completed and filed before the final examination of the candidate. This clearance sheet must be filled out and filed in the candidate's record. I have completed and filed the original term paper in art history in the Art Department office and I have given a copy to the course instructor. Course Number Year 0/tf I Yl~t1--~ Student signature Instructor signature ~a.~Adviser signature 1 Drawing Upon Themselves: Women's Self-Portraits in a Man's World A man can do well depending only upon himself and can brave public opinion; but a woman who has done well has only accomplished half her task; for what others think of her counts no less than what she in fact is (Radisch 441 ). As long as people who call themselves artists have depicted others, they have also created images of themselves. As far back as Hildegaard von Bingen in the twelfth century, and probably before, almost every artist or artisan who has picked up a pen, a brush, or a chisel has been concerned with the depiction of self. Male artists have had the ability to present themselves as they are, as subject and artist, without a division between the two. Women artists have historically traveled a slightly different, and considerably rougher path than their male counterparts. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St. -

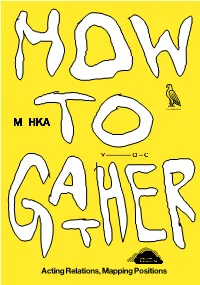

Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: the Individual HOW to GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions

Kunsthalle Wien Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: The Individual HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 3 21 Bart De Baere, Defne Ayas, Keren Cytter — Nicolaus Schafhausen — Note From Bed Background 23 9 Hanne Lippard — Marie Egger — Here’s it Editorial 25 Sergey Bratkov — Predictions on the Moon 33 Liam Gillick — Letters from Moscow 43 Li Mu — The Labourer 63 Ho Tzu-Nyen and Lee Weng-Choy — Curation is Also a Form of Transportation 77 Lee Weng-Choy — Three Degrees of Intimacy 81 Meggy Rustamova — Waiting for the Secret (Script) 85 Johanna van Overmeir — Janus 88 Janus Faced Freedom Marina Simakova Part II: In Relation Part III: Political Gestures HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 89 119 176 225 Peter Wächtler — Mián Mián and Konstantin Zvezdochotov — Anna Jermolaewa and Leather Man / Woman of Nicolaus Schafhausen — About Ezgin Altinses Vanessa Joan Müller — the Bistro Talkshow Political Extras 180 104 131 Inventing Ritual 237 Jimmie Durham — Communicative Failures Leon Kahane — A Stone and Defeats 186 Figures of Authority Andrey Shental Gabriel Lester — 108 MurMure 243 Donna Kukama — 132 Nástio Mosquito — The Cemetery for Bad Honoré δ’O and 195 SOUTH Behaviours Fabrice Hyber — Honoré δ’O — Telepathic Protocol The Ten Commandments 246 114 Saâdane Afif — On Intimacy 137 215 Play Opposite Maria Kotlyachkova, Nadia Qiu Zhijie — Vaast Colson — Gorokhova Map of the Third World Ten Side Notes as Warm Up 250 Rana Hamadeh — 140 219 Performance Script Augustas Serapinas — Andrey Kuzkin — Conversation Behind -

Sisters-In-Loss Roadmap to Healing

Road to Healing A E-book Guide to Healing from Pregnancy and Infant Loss and Infertility Welcome Sister in Loss, I am so sorry for your loss. I am not sure what brought you to me, but I'm thankful that you are here to learn, grow, and heal. Please know that the pain you are feeling is real, your loss is real, and you and your baby matter. God did not bring you to this e-book by accident, and you my Sister in Loss are loved, valued, resilient, and phenomenal. All of those tears you cried did not go unnoticed and all those prayers you prayed have been heard. I am not sure if you know Jesus Christ as your personal savior or if you have not prayed in a long while. No matter what your story is, God brought you to me for you to read this e-book, and give you a roadmap for healing. I started Sisters in Loss because I needed an outlet, a community of sisters who knew the pain I felt was real. I needed an outlet to express how my faith was shattered after my loss, and how I did not know how to exactly pray. I needed to know that God heard me even though I was mad and angry at him for taking my children so soon. This e-book is for you my Sister in Loss to lay a foundation, a roadmap toward healing, gain clarity and peace, and become victorious after loss. I have put together prayers, a devotional, and action plan for you to begin your healing now.