Alice Neel : Family 3 Alice Neel : Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice-Neel-Biography.Pdf

ALICE NEEL Biography 1900 Born in Merion Square, Pennsylvania 1984 Died in New York, NY Education 1925 Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design), Philadelphia, PA Solo Exhibitions 2022 Alice Neel: Un regard engagé, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (catalogue) 2021 Alice Neel: People Come First, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY 2019 Alice Neel: Freedom, David Zwirner, New York, NY (catalogue) Neel / Picasso, Sara Kay Gallery, New York, NY 2018 Alice Neel in New Jersey and Vermont, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels 2017 Alice Neel: The Great Society, Aurel Scheibler, Berlin (catalogue) Alice Neel, Uptown, David Zwirner, New York; traveled to Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2016 Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life, Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki; traveled to Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles; Deichtorhallen, Hamburg (catalogue) Alice Neel: The Subject and Me, Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (catalogue) 2015 Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors 1927-1978, David Zwirner, New York, NY (catalogue) Alice Neel, Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich [exhibition publication] Alice Neel, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels (catalogue) 2014 Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, Bennington Museum, Vermont Alice Neel: My Animals and Other Family, Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2013 Alice Neel: Intimate Relations, Drawings and Watercolours 1926-1982, Nordiska Akvarellmuseet, Skärhamn, Sweden (catalogue) People and Places: Paintings by Alice Neel, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul (catalogue) 2012 Alice Neel: Late Portraits & Still Lifes, David Zwirner, New York (catalogue) 2011 Alice Neel: Family, The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin (catalogue) Alice Neel: Men Only, Victoria Miro, London (catalogue) 2010 Alice Neel: Painted Truths, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas [itinerary: Whitechapel Gallery, London; Moderna Museet Malmö, Sweden] (catalogue) Alice Neel: Paintings, L.A. -

Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field

Painting the People Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field Fig. 1: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Fig. 2: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Julius Norton, ca. 1840 Sarah Elizabeth Ball, ca. 1838 Oil on canvas, 35 x 29 inches Oil on canvas, 35⅛ x 29¼ inches Bennington Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Harold C. Payson (Dorothy Norton) Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe by Jamie Franklin rastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) and Alice Neel (1900–1984) were masters of the portrait within their respective periods and cultural settings. Though separated by a hundred years and working in distinct styles and contexts, the portraits painted by Field, one of America’s best known nineteenth-century itinerant artists, and Neel, one of the most acclaimed portrait painters of the twentieth century, have a remarkable resonance with one another. Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, an exhibition at the Bennington Museum in Vermont, examines the visual, historic and conceptual relationships between the paintings of these two seemingly disparate artists. Critics, curators, biographers, friends of the artist, and the artist herself, have referenced the relationship between “folk” or “primitive” painting and Neel’s portraits. However, this is the first exhibition to examine this facet of Neel’s work directly. By looking closely at Field’s and Neel’s political, social, and artistic milieus and the subjects depicted in their portraits, the exhibition seeks to reexamine the relationship between modernism and its romantic notions of the “folk,” while providing us with a more nuanced understanding of these important artists and their work. -

THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: from Idea to Institution

4 THE JOURNAL OF THE THE MARY H. DANA WOMEN ARTISTS SERIES: From Idea to Institution BY BERYL K. SMITH Ms. Smith is Librarian at the Rutgers University Art Library During the 1960s, women began to identify and admit that social, political, and cultural inequities existed, and to seek redress. In 1966, a structural solidarity took shape with the founding of NOW (National Organization for Women). Women artists, sympathetic to the aims of this movement, recog- nized the need for a coalition with a more specific direction, and, at the height of the women's movement, several groups were formed that uniquely focused on issues of concern to women artists. In 1969 W.A.R. (Women Artists in Revolution) grew out of the Art Worker's Coalition, an anti- establishment group. In 1970 the Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee was formed, initially to increase the representation of women in the Whitney Museum annuals but later a more broad-based purpose of political and legal action and a program of regular discussions was adopted. Across the country, women artists were organizing in consciousness-raising sessions, joining hands in support groups, and picketing and protesting for the relief of injustices that they felt were rampant in the male-dominated art world. In January 1971, Linda Nochlin answered the question she posed in her now famous and widely cited article, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" Nochlin maintained that the exclusion of women from social and cultural institutions was the root cause that created a kind of cultural malnourishment of women.1 In June 1971, a new unity led the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists to threaten to sue the Los Angeles County Museum for discrimination.2 That same year, at Cal Arts (California In- stitute of the Arts) Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro developed the first women's art program in the nation.3 These bicoastal activities illustrate merely the high points of the women's art movement, forming an historical framework and providing the emotional climate for the beginning of the Women Artists Series at Douglass College. -

Drawing Upon Themselves: Women's Self-Portraits in A

DRAWING UPON THEMSELVES: WOMEN'S SELF-PORTRAITS IN A MAN'S WORLD Submitted by Monica Ann Mersch Department of Art In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 1996 CLEARANCE FOR ART HISTORY RESEARCH PAPER FOR M.F.A. CANDIDATES This paper must be completed and filed before the final examination of the candidate. This clearance sheet must be filled out and filed in the candidate's record. I have completed and filed the original term paper in art history in the Art Department office and I have given a copy to the course instructor. Course Number Year 0/tf I Yl~t1--~ Student signature Instructor signature ~a.~Adviser signature 1 Drawing Upon Themselves: Women's Self-Portraits in a Man's World A man can do well depending only upon himself and can brave public opinion; but a woman who has done well has only accomplished half her task; for what others think of her counts no less than what she in fact is (Radisch 441 ). As long as people who call themselves artists have depicted others, they have also created images of themselves. As far back as Hildegaard von Bingen in the twelfth century, and probably before, almost every artist or artisan who has picked up a pen, a brush, or a chisel has been concerned with the depiction of self. Male artists have had the ability to present themselves as they are, as subject and artist, without a division between the two. Women artists have historically traveled a slightly different, and considerably rougher path than their male counterparts. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St. -

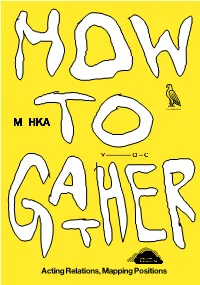

Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: the Individual HOW to GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions

Kunsthalle Wien Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: The Individual HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 3 21 Bart De Baere, Defne Ayas, Keren Cytter — Nicolaus Schafhausen — Note From Bed Background 23 9 Hanne Lippard — Marie Egger — Here’s it Editorial 25 Sergey Bratkov — Predictions on the Moon 33 Liam Gillick — Letters from Moscow 43 Li Mu — The Labourer 63 Ho Tzu-Nyen and Lee Weng-Choy — Curation is Also a Form of Transportation 77 Lee Weng-Choy — Three Degrees of Intimacy 81 Meggy Rustamova — Waiting for the Secret (Script) 85 Johanna van Overmeir — Janus 88 Janus Faced Freedom Marina Simakova Part II: In Relation Part III: Political Gestures HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 89 119 176 225 Peter Wächtler — Mián Mián and Konstantin Zvezdochotov — Anna Jermolaewa and Leather Man / Woman of Nicolaus Schafhausen — About Ezgin Altinses Vanessa Joan Müller — the Bistro Talkshow Political Extras 180 104 131 Inventing Ritual 237 Jimmie Durham — Communicative Failures Leon Kahane — A Stone and Defeats 186 Figures of Authority Andrey Shental Gabriel Lester — 108 MurMure 243 Donna Kukama — 132 Nástio Mosquito — The Cemetery for Bad Honoré δ’O and 195 SOUTH Behaviours Fabrice Hyber — Honoré δ’O — Telepathic Protocol The Ten Commandments 246 114 Saâdane Afif — On Intimacy 137 215 Play Opposite Maria Kotlyachkova, Nadia Qiu Zhijie — Vaast Colson — Gorokhova Map of the Third World Ten Side Notes as Warm Up 250 Rana Hamadeh — 140 219 Performance Script Augustas Serapinas — Andrey Kuzkin — Conversation Behind -

191 Figure 1. Elaine De Kooning, Black Mountain #16, 1948. Private Collection

Figure 1. Elaine de Kooning, Black Mountain #16, 1948. Private Collection. 191 Figure 2. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled, #15, 1948. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 192 Figure 3. Willem de Kooning, Judgment Day, 1946. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 193 Figure 4. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Untitled #15, 1948. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 194 Figure 5. Hans Hofmann, Ecstasy, 1947. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum. 195 Figure 6. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled 11, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 196 Figure 7. Elaine de Kooning, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 197 Figure 8. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 198 Figure 9. Elaine de Kooning, Detail, Self Portrait #3, 1946. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 199 Figure 10. Elaine de Kooning, Untitled 12, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 200 Figure 11. Elaine de Kooning, Black Mountain #6, 1948. Salander O’Reilly Galleries, New York. 201 Figure 12. Grace Hartigan, Frank O’Hara, 1966. National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 202 Figure 13. Elaine de Kooning, Kaldis #12, 1978. Private Collection. 203 Figure 14. Elaine de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, 1956. Private Collection. 204 Figure 15. Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, 1926-36. Whitney Museum of Art, New York. 205 Figure 16. Elaine de Kooning, Al Lazar #2, 1954. Private Collection. 206 Figure 17. Elaine de Kooning, Conrad #2, 1950. Private Collection. 207 Figure 18. Elaine de Kooning, JFK, 1963. -

Press Release (PDF)

s h f a p PRESS RELEASE: Front gallery: Madeline Donahue: Attachments paintings, drawings, & sculpture Rear gallery: Anne Harvey: Arabesques drawings September 4 – October 6, 2019 Opening reception: Wednesday, September 4th, 6- 8pm In our front gallery, SHFAP presents Madeline Donahue: Attachments, a collection of paintings, drawings, and sculpture from the Brooklyn based artist. In our rear gallery, we are showing Anne Harvey: Arabesques, drawings by the American expatriate and painter (1916-1967) who spent the majority of her life in Paris. Madeline Donahue did not see her perspective of motherhood in art so she created it. Her paintings explore the overwhelming absurdity, intimacy, and joy of caring for another person. She focuses on the surreal quality and physicality of the mother and child relationships. Her work features a maternal figure attempting to perform basic aspects of her day as her child clings to her hair and limbs, nonchalantly playing on her body. In an interview with Charlotte Jansen of Elephant Magazine, Donahue states, “At a certain point, instead of shaking off parenting in the studio, I just decided to go in and [say], “OK, this happened today, I’m going to draw it.” That turned into this really fun experience of drawing and painting my perception of motherhood.” Jansen states that “Donahue might not deliberately address the stigma of birth and motherhood in art, but it exists nonetheless. The names she mentions when I ask her which artists she admires who have made art about the subject are familiar: Louise Bourgeois, Alice Neel, Chantal Joffe, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Katherine Bradford, and ‘Marlene Dumas’s baby paintings.’” Madeline Donahue studied at Tufts University and The School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA. -

Alice Neel: an Instrumental Case Study

Alice Neel: An Instrumental Case Study Exploring a Mother’s Stylistic Elements in Artwork in Response to her Infant Child’s Death A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Johnna S. Butler in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Creative Arts in Therapy June 2008 ii Dedications With love and gratitude, I dedicate this thesis to my father John Butler. iii Acknowledgments I give thanks to Bobby. iv Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………..………….vi LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………………vii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………..………….......ix 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………… 1 2. LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………………………………………. 5 2.1. Infant Loss and Its Causes………………………………………………………………. 5 2.2. Grief………………………………………………………………………..……………. 6 2.2.1. Definition of Grief………………………………………………………………… 6 2.2.2. Stages of Grief and Grief Work…………………………………………………… 7 2.2.3. Normal Grief………………………………………………………………………. 8 2.2.4. Stages versus Tasks………………………………………………………………..12 2.2.5. Complicated Grief…………………………………………………………………15 2.2.6. Chronic Grief Reactions…………………………………………………………..15 2.2.7. Grief of Mothers after Infant Loss……………………………………………….. 16 2.2.8. Postpartum Depression……………………………………………………………18 2.2.7. Supporting Bereaved Parents within a Medical Setting…………………………. 21 2.3. Treatment of Grief due to Infant Loss…………………………………………………. 22 2.3.1. Creative Arts and Art Therapy Treatment in Bereavement……………………… 23 2.4. Alice Neel……………………………………………………………………………… 27 2.4.1. The Family………………………………………………………………………...28 2.4.2. After the Death of the Child………………………………………………………30 2.4.3. After Birth of Isabetta…………………………………………………………......31 2.4.4. After Loss of Child and Husband, Philadelphia Summer 1930, Breakdown……..33 2.4.5. After Hospitalization………………………………………………………………37 2.4.6. Isabetta…………………………………………………………………………….40 3. METHODOLOGY…………………………………………………………………………. 42 3.1. -

Alice Neel (American, 1900-84) – Artist Resources

Alice Neel (American, 1900-84) – Artist Resources Alice Neel Estate: biography, artwork, exhibitions, press and publications Neel at the Victoria-Munro Gallery in London Neel at David Zwirner Gallery in New York Listen to excerpts from interviews with Neel in 1971 and 1975 on Getty Podcasts Radical Women series “The road that I pursued, and the road that I think keeps you an artist, was that no matter what happened to me, you still keep on painting,” explains Neel in a 1979 televised interview conducted through the Inside New York’s Art World series. “You should just keep on painting no matter how difficult it is, because this is all part of experience.” Neel, 1980 Photograph: Frank Leonardo/New York Post/Getty Images Explaining her aversion to the wave of abstraction in New York in the 1950s, Neel tells critic and fellow artist Don Gray in a televised interview, “I wanted to do as I pleased. I think art is history. I like to paint what was around me…I’d rather do some other kind of work than make my art conform to make some kind of money.” “I try to capture the person, 100% the person, and then also the spirit of the age, the zeitgeist,” reveals Neel in a 1983 video interview at the Maryland Institute College of Art. In 2017, art critic Hilton Als curated a show at David Zwirner showcasing the portraits Neel painted while living in Spanish Harlem and the Upper Westside in New York, in which, according to Als, Neel was at her height of powers for representing the “drama of being.” The Centre Pompidou in Paris is scheduled to exhibit a comprehensive retrospective of Neel’s paintings in the Neel, 1944 summer of 2020, Un Regard Engagé. -

Neel, Alice Canary, Girl, Fire Escape

Date: October 4, 2011 EI Presenter: Mary Alice Dwyer Artwork Title: Canary, Girl and Fire Escape – Portrait Year Created: 1938 Artist: Alice Neel (1900-84) These are the 5 most essential aspects of this work of art: 1. Artist defiantly painted figurative work during the height of Abstract Expressionism 2. Drawing is first and foremost to the artist 3. Use of line and color to stress a psychological state or emotion 4. Suggests an identification with the small and powerless 5. Engages the emotions of the viewer Questions I would ask when viewing this object with visitors: 1. How did the artist use lines, color and texture? 2. How does this painting make you feel? Why? 3. What do you think the artist was trying to say here? 4. Is the window open? What else? 5. How many birds do you see? About the Artist: Alice Neel came of age at the height of the Women’s Suffrage Movement. In the 1970s she was hailed as an icon for the Feminist movement. She called herself “a collector of souls”. She met her first husband, Carlos Enriguez, at art camp while attending the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. After her graduation in 1925, they moved to Havana living with Carlos’ wealthy parents. Neel was embraced by the young avante-garde set of artists, musicians, and writers, and it was here that she developed her life-long political consciousness and her commitment to equality. After the birth of their first daughter, the family moved to NYC. Just before her first birthday the child died of diphtheria.In 1928, Isabetta was born.