Singapore Judgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

FIC-Prop-65-Notice-Reporter.Pdf

FIC Proposition 65 Food Notice Reporter (Current as of 9/25/2021) A B C D E F G H Date Attorney Alleged Notice General Manufacturer Product of Amended/ Additional Chemical(s) 60 day Notice Link was Case /Company Concern Withdrawn Notice Detected 1 Filed Number Sprouts VeggIe RotInI; Sprouts FruIt & GraIn https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers Cereal Bars; Sprouts 9/24/21 2021-02369 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. SpInach FettucIne; 02369.pdf Sprouts StraIght Cut 2 Sweet Potato FrIes Sprouts Pasta & VeggIe https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers 9/24/21 2021-02370 Sauce; Sprouts VeggIe Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. 3 Power Bowl 02370.pdf Dawn Anderson, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02371 Sprouts Farmers OhI Wholesome Bars Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 4 Market, Inc. 02371.pdf Brad's Raw ChIps, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02372 Sprouts Farmers Brad's Raw ChIps Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 5 Market, Inc. 02372.pdf Plant Snacks, LLC; Plant Snacks Vegan https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02373 Sprouts Farmers Cheddar Cassava Root Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 6 Market, Inc. ChIps 02373.pdf Nature's Earthly https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl ChoIce; Global JuIces Nature's Earthly ChoIce 9/24/21 2021-02374 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- and FruIts, LLC; Great Day Beet Powder 02374.pdf 7 Walmart, Inc. Freeland Foods, LLC; Go Raw OrganIc https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02375 Ralphs Grocery Sprouted Sea Salt Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 8 Company Sunflower Seeds 02375.pdf The CarrIngton Tea https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl CarrIngton Farms Beet 9/24/21 2021-02376 Company, LLC; Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Root Powder 9 Walmart, Inc. -

Irresistible Chinese Cuisine

1 Irresistible Chinese Cuisine By: Yidi Wang Online: <https://legacy.cnx.org/content/col29267/1.4> This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Yidi Wang. Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Collection structure revised: 2019/05/21 PDF Generated: 2019/05/21 21:33:04 For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see the "Attributions" section at the end of the collection. 2 This OpenStax book is available for free at https://legacy.cnx.org/content/col29267/1.4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Brief introduction 5 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 Eight Regional Cuisine 6 1.3 Culinary Culture 13 Index 19 This OpenStax book is available for free at https://legacy.cnx.org/content/col29267/1.4 1.1 Introduction 1 Brief introduction Exhibit 1.1 Chinese Eight Regional Cuisines. Introduction to Chinese Cuisinology If I need to choose what kind of food I will be fed for the rest of my life, I will choose Chinese cuisine without any hesitation. - Yidi Wang Learning Objectives: • Capacity to integrate knowledge and to analyse and evaluate a Chinese cuisine at a local and global levels, even when limited information is available. • Capacity to identify the general type of a Chinese dish. • Capacity to appreciate the differences between Western and Chinese culinary cultures. • Capacity to comprehend basic principles of Anhui Cuisine. • Capacity to recognize some unorthodox Chinese dishes. Links and contents 1.1 Eight Regional Cuisines 1.2 Culinary Culture 6 Chapter 1 Brief introduction Introduction Chinese cuisine is an important part of Chinese culture, which includes cuisine originating from the diverse regions of China, as well as from Chinese people in other parts of the world. -

Kitchen Side

KITCHEN SIDE OLD FASHION BEIJING SOUP |tofu, bamboo, carrot, 4,20 egg, shitake D A WONTON SOUP|homemade Wan Tan with Pork and coriander, L 4,90 mushroom, pak Choi, egg pancake stripes A S tofu,pak choi and mushroom 3,90 + TOFU SOUP | P CHINACY SALAD |tofuskin with carrot and paprika U 4,90 Edamame, Fungus O S SEAWEED SALAD SHANGHAI STYLE | 5,20 pickled seaweed GUA BAO BAO ZI THE CLASSIC PORK 4,50 XIAO LONG BAO (3 pcs.) 5,90 braised pork belly, cucumber, carrot, peanuts, pickled soup dumplings with pork vegetables JIANG BAO (3 pcs.) 6,20 CRISPY CHICKEN 4,50 porkbelly with fermented soybeanpaste CAI BAO (3 pcs.) 6,20 crispy chicken, cucumber, carrot, red cabbage, homemade Mayo smoked tofu with pak choi and shitake VEGGIE 4,50 CHA SIU BAO (3 pcs.) 6,20 grilled pork with cantonese BBQ sauce eggplant, crispy cracker, szechuan sauce, carrot BAO ZI TRIO (3 psc.) 6,20 1 psc.Jiang Bao,1 psc.Cai Bao und 1 psc.Cha Siu Bao Some of our food contains allergens. Please speak to a member of staff or more information. All prices are in Euros including VAT. TAPAS/SIDE DISHES OH! HONEY WINGS 6,20 chickenwings with homemade honey sauce POPCORN CHICKEN 6,80 crispy chicken balls with homemade Mayo KIMCHEESY RICE BALL (3 pcs.) 6,20 Kimchi,Gouda,Rice,Sesam and Homemade figs Mayonnaise CHILI & PEPPER CHICKEN 6,80 chicken thighs with cucumber, szechuan pepper, chili sauce and peanuts CHINACY NOODLES 5,90 homemade noodle with onion oil, roasted onions and soy sauce egg DAN DAN DON 5,90 porkbelly ,shitake,carrot with fermented soybeanpaste ,Kewpie Mayo,Yuk Song,Rice -

Board of Directors

HAWAII FOODBANK Board of Directors BOARD OFFICERS Mark Tonini Ashley Nagaoka Jason Haaksma Hawaii Foodservice Alliance Hawaii News Now Enterprise Holdings Jeff Moken Chair Jeff Vigilla Patrick Ono Michelle Hee Hawaiian Airlines Chef Point of View Matson Inc. ‘Iolani School Christina Hause James Wataru Tim Takeshita Ryan Hew First Vice Chair United Public Enterprise Holdings Hew and Bordenave LLP Kaiser Permanente Workers Union, AFSCME Local 646 Beth Tokioka Blake Ishizu David Herndon Kaua‘i Island Utility Hawaii Foodservice Second Vice Chair Jason Wong Cooperative Alliance Hawaii Medical Service Sysco Hawaii Association Sonia Topenio Crystine Ito Lauren Zirbel Bank of Hawaii Rainbow Drive-In James Starshak Hawaii Food Industry Secretary Association Laurie Yoshida Woo Ri Kim Community Volunteer Corteva Agriscience Girl Scouts of Hawai‘i EXECUTIVE Neill Char PARTNERS BOARD ALAKA‘I Reena Manalo Treasurer YOUNG LEADERS HDR Inc. First Hawaiian Bank Chuck Cotton iHeartMedia Toby Tamaye Del Mochizuki Ron Mizutani Chair UHA Health President & CEO Dennis Francis AT Marketing LLC Insurance Hawaii Foodbank Honolulu Star-Advertiser Hannah Hyun Nicole Monton BOARD OF DIRECTORS D.K. Kodama Marketing Committee MidWeek D.K. Restaurants Chair Scott Gamble Good Swell Inc. Jay Park LH Gamble Co. Katie Pickman Park Communications Hawaii News Now Christina Morisato Terri Hansen-Shon Events Committee Chair Kelly Simek Terri Hansen & EMERITUS Hawaiian Humane Society KHON2 Associates Inc. ADVISORY BOARD Maile Au Randy Soriano Denise Hayashi Cindy Bauer University of Hawaii The RS Marketing Yamaguchi Surfing the Nations Foundation Group Hawaii Wine & Food Festival Jade Moon Kelsie N. Cajka Kai Takekawa Community Volunteer Blue Zones Project – Zephyr Insurance Peter Heilmann Hawaii Co. -

Sichuanc Ookery

Simple Cooking ISSUE NO. 79 Annual Food Book Review FOUR DOLLARS SSICHUAN CCOOKERY Fuchsia Dunlop (Michael Joseph, £20, 276 pp.). In 1994, Fuchsia Dunlop went to the provincial capital, Chengdu, to study at Sichuan University. But she al- ready knew that her real interest was that area’s cook- ing, a subject that might not have been taught where she was officially enrolled but certainly was at a nearby short-listed famous cooking school, the Sichuan Institute of Higher SOUTHERN B ELLY: THE U LTIMATE F OOD L OVER’S C OMPANION Cuisine. So, one sunny October afternoon, she and a TO THE SOUTH, John T. Edge (Hill Street, $24.95, 270 college mate set out on bicycles to find it. pp.). Although the phrase might lend itself to misread- We could hear from the street that we had arrived. Fast, ing, I mean nothing but respect (and refer to nothing but regular chopping, the sound of cleavers on wood. Upstairs, culinary matters) when I call John T. Edge “The Mouth in a plain white room, dozens of apprentice cooks in white of the South.” There are reasons beyond this book say overalls were engrossed in learning the arts of sauces. this, but—so far as supporting evidence is required—it Chillies and ginger were being pulverized with pairs of will certainly do. In these pages you will not only be taken cleavers on tree-trunk chopping-boards, Sichuan to the most interesting and plainly best Southern eater- peppercorns ground to a fine brown powder, and the students scurried around mixing oils and spices, fine- ies, no matter how lowly or obscurely located, but you tuning the flavours of the rich dark liquids in their will learn pretty much all there is to know about them crucibles. -

EWC/EWCA 50Th Anniversary International Conference 2010 Honolulu, Hawai‘I | July 2 –5, 2010

Leadership and Community Building in the Asia Pacific Region EWC/EWCA 50th Anniversary International Conference 2010 Honolulu, Hawai‘i | July 2 –5, 2010 Hosted by the East-West Center and the East-West Center Association We are proud to support the East-West Center, commemorating fifty years of collaboration, expertise and leadership. ALA MOANA CENTER HYATT REGENCY WAIKIKI ROYAL HAWAIIAN HOTEL HILTON HAWAIIAN VILLAGE WHALERS VILLAGE THE SHOPS AT WAILEA WWW.TORIRICHARD.COM EWC/EWCA 50th Anniversary International Conference 2010 Honolulu, Hawai‘i | July 2 –5, 2010 Leadership and Community Building in the Asia Pacific Region Contents Welcome Letters 2 Overview Summary of Conference Schedule 6 East-West Center Day – Open House 9 Detailed Conference Schedule 11 Distinguished Alumni Awards 24 Outstanding Volunteer Awards 26 Outstanding Chapter Awards 27 East-West Center Association Makana Award 27 Co-chairs and Members of Conference Committee & Honor Roll 28 You Can Help Celebrate Our 50th Year 32 East-West Center Association (EWCA) Alumni Scholarship Fund 33 Sponsors 35 Conference Participants 36 Panel Presenters and Moderators 49 Past EWC/EWCA Conferences and Events 56 East-West Center Campus Location Map 57 Hawai‘i Convention Center Maps 58 2 3 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Tel: 808.944.7103 Fax: 808.944.7106 EastWestCenter.org July 2, 2010 Office of the President Dear East-West Center Alumni, Associates, and Friends: Welcome to our Golden Jubilee Conference! The conference committee has planned events that will celebrate the Center’s 50th Anniversary, invoke memories, provide us with new opportunities to build bridges across Asia Pacific cultures and to focus on significant issues in the region. -

Foundation Build Your

May + June 2014 www.kcourhealthmatters.com Build Your Health Firmon a FoundationTaking care of your bones and joints is one of the best things you can do for your body. Arthritis Type Conditions Impact Millions of People GET SMART — GRILL HEALTHY! Win Your Kids’ Heart — Make Summer FUN Still feeling chronic pain from your injury or surgery? Anyone can have chronic pain. Sometimes surgery, an injury, or an accident can result in chronic nerve pain. Nerve pain is often described as a shooting, burning or stabbing sensation. Some of the incidents that can result in this type of nerve pain include: Injuries Surgeries Accidents Falls Burns Our clinic is conducting a clinical research study to examine the safety and effectiveness of an investigational medication in reducing chronic nerve pain when compared with placebo (inactive substance). To find out more, please contact us at the number below. Kansas City Bone & Joint Clinic Call (Mon-DivisionFri): of913 Signature-381 Medical-5225 Group extof KC, PA351 10701 Nall Ave., Suite 200, Overland Park, KS 66211 207611 Study Flyer v1.0 US (English) 16July13 Phone:Contact (913) 381person:-5225 extJean 351 StudyDavidson Nurse | ClinicalR [email protected] Contents VOL. 9, ISSUE 3 DEPARTMENTS 12 CAREER SPotLIGHT Career Opportunities in Health Services Administration By OHM Staff Health administration positions are forecast to grow quickly over the next ten years. 20 HEALTH What Are Arthritic and Rheumatic Diseases? By OHM Staff According to the Centers for Dis- ease Control (CDC), 22.7 million 16 (9.8% of all adults) have arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity COVER STORY limitations. -

Group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data

group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data Business_ID Program Identifier PR0088142 MOD PIZZA PR0089582 ANCESTRY CELLARS, LLC PR0046580 TWIN RIVERS GOLF CLUB INC PR0042088 SWEET NECESSITIES PR0024082 O'CHAR CROSSROADS PR0081530 IL SICILIANO PR0089860 ARENA AT SEATTLE CENTER - Main Concourse Marketplace 7 PR0017959 LAKE FOREST CHEVRON PR0079629 CITY OF PACIFIC COMMUNITY CENTER PR0087442 THE COLLECTIVE - CREST PR0086722 THE BALLARD CUT PR0089797 FACEBOOK INC- 4TH FLOOR PR0011092 CAN-AM PIZZA PR0003276 MAPLE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PR0002233 7-ELEVEN #16547P PR0089914 CRUMBL COOKIES PR0089414 SOUL KITCHEN LLC PR0085777 WILDFLOWER WINE SHOP & BISTRO PR0055272 LUCKY DEVIL LATTE PR0054520 THAI GINGER Page 1 of 239 09/29/2021 group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data PR0004911 STOP IN GROCERY PR0006742 AMAZON RETAIL LLC - DELI PR0026884 Seafood PR0077727 MIKE'S AMAZING CAKES PR0063760 DINO'S GYROS PR0070754 P & T LUNCH ROOM SERVICE @ ST. JOSEPH'S PR0017357 JACK IN THE BOX PR0088537 GYM CONCESSION PR0088429 MS MARKET @ INTENTIONAL PR0020408 YUMMY HOUSE BAKERY PR0004926 TACO BELL #31311 PR0087893 SEATTLE HYATT REGENCY - L5 JR BALLROOM KITCHEN & PANTRIES PR0020009 OLAFS PR0084181 FAIRMOUNT PARK ELEMENTARY PR0069031 SAFEWAY #1885- CHINA DELI / BAKERY PR0001614 MARKETIME FOODS - GROCERY PR0047179 TACO BELL PR0068012 SEATTLE SCHOOL SUPPORT CENTER/ CENTRAL KITCHEN PR0084827 BOULEVARD LIQUOR PR0006433 KAMI TERIYAKI PR0052140 LINCOLN HIGH SCHOOL Page 2 of 239 09/29/2021 group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data PR0086224 GEMINI FISH TOO -

Seoul Hot Chicken Steamed Baos 7.5 Fluffy Buns (Think: Deliciously Bouncy Clouds) Filled with Seoul Hot Chicken

ST. PETERSBURG, FL Rip.Rip. Dip.Dip. Repeat.Repeat. TwoTwo MalaysianMalaysian flatbreads,flatbreads, servedserved withwith aa sideside ofof ourour signaturesignature currycurry sauce.sauce. 55 HANDHELDS Seoul Hot Chicken Steamed Baos 7.5 Fluffy buns (think: deliciously bouncy clouds) filled with Seoul Hot Chicken Chicken Egg Rolls 5 Egg noodle wrap, cabbage, carrots Spring Rolls 4 Crisp wrap and shredded veggies Summer Rolls 4.5 Chilled rice wrap, noodles, lettuce, basil, mint and bean sprouts. add shrimp 1 DIM SUM Yi-Yi’s Chicken Dumplings 7 Our Auntie’s classic recipe hand-rolled daily, wok-seared or steamed, served with a sweet soy dipping sauce. Sichuan Wontons 8 Chicken, shrimp, peanut chili sauce Golden Wontons 7.5 Hand-made daily filled with chicken, shrimp and mushrooms, fried to a crisp and served with a sweet chili dipping sauce. MEAT + SEAFOOD Siu Yoke 8 Crisp pork belly, hoisin dipping sauce Char Siu 8 Pork shoulder, sweet soy, spring onions Street Skewers Flavored to perfection and cooked over a 1000° wood-burning grill. Your choice of: BULGOGI BEEF 9 BULGOGI CHICKEN 8 SATAY CHICKEN 8 Korean Twice Fried Wings 8.5 Sauced in garlic gochujang and topped with peanuts, sesame and cilantro. Hawkers Wings 7.5 BATTERED or NAKED Choice of sauce: sweet thai chili, hainanese , honey sriracha , spring onion ginger or rub: five-spice, chuan jerk Coconut Shrimp 8 with curry dipping sauce. LIGHT Hawker’s Delight 7 Saucy blend of wok-seared tofu, broccoli, carrots, napa (pro tip: the cabbage, not the city), bell peppers and straw mushrooms. Green Papaya & Shrimp Salad 8 Carrots, basil, cilantro, mango, fried shallots, roasted peanuts, Vietnamese vinaigrette Crispy Tofu Bites 6 Edamame 4 add chili and garlic 1 Five-Spice Green Beans 6 Lightly battered, fried to a crisp, tossed in our signature five-spice seasoning Viet Bún Salad 8.5 Lemongrass pork, fresh basil, rice noodles, golden wonton crisps, peanuts, veggies and a spring roll. -

J40668-UOB BI Dec FA2.Indd

OVER 2,000,000 REASONS TO CELEBRATE TURNING 20 2 Million Air Miles To Be Won. We’re turning 20 and are celebrating it by giving you a chance to tour the world. You and your loved one can now stand a chance to fl y to USA, Europe, South Africa, Japan or Australia and back, on fi rst class*. Simply charge S$50 to your UOB Card from now to 8 Feb 2009 for a chance to win. A Prize A Week, For 20 Weeks. Another celebration not to be missed. We’re giving away a prize every week, for 20 weeks. From LCD TVs, to a year’s supply of fuel from Shell or groceries from Cold Storage! Every S$50 charged to your UOB Card from 18 Sep 2008 to 8 Feb 2009, also earns you a chance to win in our weekly draw. Step Up The Celebrations. What’s more! We’ll be matching every S$5,000 you spend with 10 bonus chances and double chances for every S$50 spent overseas. So the more you use your UOB Card, the more chances you get! Visit uobgroup.com for full details. * Countries stated are for illustration purpose and subject to availability of tickets under Frequent Flyer Programme of the airlines. bonappetit Imperial Treasure Restaurants Festive Dining Complimentary $18 return-visit voucher with min. spend of $100 on food items Cantonese Cuisine (Great World City #02-06), Tel: 6732 2232 Cantonese Cuisine (Crowne Plaza T3 #01-02), Tel: 6822 8228 Teochew Cuisine (Ngee Ann City #04-20A/21), Tel: 6736 2118 Nan Bei Restaurant (Ngee Ann City #05-12/13), Tel: 6738 1238 La Mian Xiao Long Bao (Marina Square #02-138J), Tel: 6338 2212 Jing Chuan Hu Yang Noodle Restaurant (Suntec City Mall #B1-011), Tel: 6339 3118 • Valid from 8 Jan - 9 Feb 2009 • Voucher is redeemable with a min. -

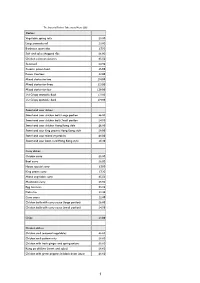

The Imperial Menu 2021

The Imperial Palace Take away Menu 2021 Starters Vegetable spring rolls £3.80 Large pancake roll £3.80 Barbecue spare ribs £7.50 Salt and spicy chopped ribs £6.80 Chicken satay on skewers £5.50 Seaweed £4.50 Sesame prawn toast £5.00 Prawn Crackers £2.00 Mixed starter for two £14.00 Mixed starter for three £21.00 Mixed starter for four £28.00 1/4 Crispy aromatic duck £11.00 1/2 Crispy aromatic duck £19.80 Sweet and sour dishes Sweet and sour chicken balls Large portion £6.80 Sweet and sour chicken balls Small portion £4.50 Sweet and sour chicken Hong Kong style £6.80 Sweet and sour king prawns Hong Kong style £8.00 Sweet and sour mixed vegetables £6.00 Sweet and sour bean curd Hong Kong style £6.30 Curry dishes Chicken curry £5.80 Beef curry £6.00 House special curry £7.00 King prawn curry £7.30 Mixed vegetable curry £5.50 Mushroom curry £5.50 Egg fried rice £3.60 Plain rice £3.30 Curry sauce £2.80 Chicken balls with curry sauce (large portion) £6.80 Chicken balls with curry sauce (small portion) £4.50 Chips £3.00 Chicken dishes Chicken and seasonal vegetables £6.60 Chicken and cashew nuts £6.60 Chicken with fresh ginger and spring onions £6.60 Kung po chicken (sweet and spicy) £6.60 Chicken with green peppers in black bean sauce £6.60 1 Chicken with mushrooms in black bean sauce £6.60 Chicken and satay sauce £6.60 Chicken Sze Chuan style (hot and spicy) £6.60 Chicken and mushrooms in oyster sauce £6.60 Chicken and lemon sauce £6.60 Sweet chilli chicken £6.60 Hon Fei chicken £6.60 Salt and spicy chicken £6.60 Chicken and yellow bean sauce