The Imaginarium of Terry Gilliam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam

H-Film A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam Discussion published by Elif Sendur on Thursday, March 5, 2020 original authorship: [email protected] A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam Edited by Ian Bekker, Sabine Planka and Philip van der Merwe Terry Gilliam is not only popular for being part of the Monty Python-troup but also for the movies he has directed in his own style, such as Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Fisher King (1991), 12 Monkeys (1995) and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009). From dystopian to fantastic and magical settings, and worlds often populated by bizarre figures, Gilliam’s movies are united by their bizarreness in various ways. In this regard his oeuvre offers an incredibly fertile ground for critical examination, analysis and discussion. This anthology is designed to honour the year of Terry Gilliam’s eightieth birthday and is expected to be part of the A Critical Companion to Popular Directors series edited by Adam Barkman and Antonio Sanna. The goal is to showcase previously-unpublished essays that explore Gilliam’soeuvre from multidisciplinary perspectives. Contributions should focus on movies directed by Gilliam, starting with his debut (together with Terry Jones) Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), followed by his first solo debut Jabberwocky (1977), right up until his latest movie, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018). We are particularly interested in interdisciplinary approaches to the subject which can illuminate the diverse facets of this director’s work as well as his visual style. There are several themes worth exploring when analyzing Gilliam’s works, utilizing any number of theoretical frameworks of one’s choosing. -

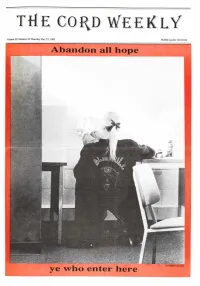

The Cord Weekly

THE CORD WEEKLY Volume 29, Number 25 Thursday Mar. 23,1989 Wilfrid Laurier University Abandon all hope ye who enter here Cord Photo: Liza Sardi The Cord Weekly 2 Thursday, March 23,1989 THE CORD WEEKLY |1 keliv/f!rent-a-car ; SAVE $5.00 ! March 23,1989 Volume 29, Number 25 ■ ON ANY CAR RENTAL ■ I Editor-in-Chief Cori Ferguson ■ NEWS Editor Bryan C. Leblanc Associate Jonathan Stover Contributors Tim Sullivan Frances McAneney COMMENT ■ ■ Contributors 205 WEBER ST. N. Steve Giustizia l 886-9190 l FEATURES Free Customer Pick-up Delivery ■ Editor vacant and Contributors Elizabeth Chen ENTERTAINMENT Editor Neville J. Blair Contributors Dave Lackie Cori Cusak Jonathan Stover Kathy O'Grady Brad Driver Todd Bird SPORTS Editor Brad Lyon Contributors Brian Owen Sam Syfie Serge Grenier Lucien Boivin Raoul Treadway Wayne Riley Oscar Madison Fidel Treadway Kenneth J. Whytock Janet Smith DESIGN AND ASSEMBLY Production Manager Kat Rios Assistants Sandy Buchanan Sarah Welstead Bill Casey Systems Technician Paul Dawson Copy Editors Shannon Mcllwain Keri Downs Contributors \ Jana Watson Tony Burke CAREERS Andre Widmer 112 PHOTOGRAPHY Manager Vicki Williams Technician Jon Rohr gfCHALLENGE Graphic Arts Paul Tallon Contributors Liza Sardi Brian Craig gfSECURITY Chris Starkey Tony Burke J. Jonah Jameson Marc Leblanc — ADVERTISING INFLEXIBILITY Manager Bill Rockwood Classifieds Mark Hand gfPRESTIGE Production Manager Scott Vandenberg National Advertising Campus Plus gf (416)481-7283 SATISFACTION CIRCULATION AND FILING Manager John Doherty Ifyou want theserewards Eight month, 24-issue CORD subscription rates are: $20.00 for addresses within Canada inacareer... and $25.00 outside the country. Co-op students may subscribe at the rate of $9.00 per four month work term. -

Sabina Stumberger

Divided God Sabina Stumberger Sabina Štumberger, visual anthropologist and video maker / researcher in the field of minority group issues; university lecturer in the field of visual art. Creative director and owner of an interactive media and video production company vmedia, Soho - London, UK, dealing with interactive media, DVD creation, screen design, graphic design and content production. She is actively managing the company since 2000, while remaining in the role of the designer and video content producer/maker. Some notable projects include Ghost in the Shell (Manga), Withnail and I (Handmade), Time Bandits (Handmade) inclusive of the documentary featuring work of Terry Gilliam and Michael Palin (Monty Python). Some notable clients include British Film Institute, Universal Films, Fox, Granada Television, Sony Pictures and Paramount. Some private projects: ‘We Have No Word for War’, 1995, featuring the culture of travelers; shown on festivals in Europe and overseas, NL; script and field collaboration; editor for the documentary ‘Bosnian Muslims – The Fate of World’, 1995, featuring the history of war in Bosnia; documentary projects of the Romani gatherings in Camargue, France; direction, script and edit, between 1990 and 1995. Part of the foundation group of the field project in the Romani settlements in Krsko, Slovenia in the capacity of anthropologist, researcher and video maker targeting the stereotypes between the settlers' and the Romani communities. By living within the community she became a cultural/social mediator between the two cultures and initiated the interactive creative projects in Romani settlements by using photographic and video camera as objects of communication and research.She is a visiting lecturer at the Communications for Illustrations department at the School of Art and Design, Derby since 2006 and a practicing visual artist focusing on site-specific and public art, exhibiting in the UK and overseas since 1990. -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

Switchblade Comb" by Mobius Vanchocstraw

00:00:00 Music Music "Switchblade Comb" by Mobius VanChocStraw. A jaunty, jazzy tune reminiscent of the opening theme of a movie. Music continues at a lower volume as April introduces herself and her guest, and then it fades out. 00:00:08 April Wolfe Host Welcome to Switchblade Sisters, where women get together to slice and dice our favorite action and genre films. I'm April Wolfe. Every week, I invite a new female filmmaker on—a writer, director, actor, or producer—and we talk in-depth about one of their fave genre films, perhaps one that influenced their own work in some small way, and today I'm very excited to have screenwriter/playwright Claire Kiechel with me. Hi, Claire! 00:00:28 Claire Guest I'm so happy to be here! Kiechel [Music fades out.] 00:00:30 April Host For those of you who aren't as familiar with Claire's work, please let me give you an introduction. Claire is a bi-coastal theatre-maker and film and TV writer. She earned her BA from Amherst College before jumping up to the New School of Drama for her MFA. Since then she's stayed very busy, receiving commissions from Actors Theatre of Louisville, South Coast Rep, and the Alley Theatre. Her plays include Paul Swan is Dead and Gone at the Civilians at Torn Page, Sophia at Alley Theatre All New Festival in 2019—with an upcoming world premiere at the Alley in 2020. She's also brought sci-fi to the stage with Pilgrims at the Gift Theatre, which got a spot on the Kilroys' The List in 2016. -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

Don Quijote Por Tierras Extranjeras

Coordinador: Hans Christian Hagedorn Don quijote por tierras extranjeras colecclón HUMANIDADES DON QUIJOTE POR TIERRAS EXTRANJERAS Estudios sobre la recepción internacional de la novela cervantina This One AASZ-32X-UKRJ DON QUIJOTE POR TIERRAS EXTRANJERAS Estudios sobre la recepción internacional de la novela cervantina Juan Bravo Castillo Ana Fe Gil Serra Hans Christian Hagedorn Georg Pichler Francisco M. Rodríguez Sierra Ramón García Pradas María Teresa Pisa Cañete Beatriz González Moreno Eduardo de Gregorio Godeo y Silvia Molina Plaza Ana Ma Manzanas Calvo y Jesús Benito Sánchez Ángel Mateos- Aparicio Martín- Albo Elena Elisabetta Marcello María Cristina Alonso Vázquez José María Ortiz Martínez Juan José Pastor Comín Lydia Reyero Flores Hans Christian Hagedorn (coord.) Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha Cuenca, 2007 DON QUIJOTE por tierras extranjeras : estudios sobre la recepción internacional de la novela cervantina / Juan Bravo Castillo ... [et al.] ; coordinador, Hans Christian Hagedorn- Cuenca : Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2007 376 p. ; 22 cm- (Humanidades ; 89) ISBN 978-84-8427-448-3 1 . Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de ( 1 547- 1616). Don Quijote de la Mancha - Influencia 2. Estética de la recepción 3. Literatura - Historia y crítica I. Bravo Castillo, Juan II. Hagedorn, Hans Christian, coord. III. Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, ed. IV. Serie 821.134.2 Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de 7 Quijote 1.07 82.09 Esta edición es propiedad de EDICIONES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA y no se puede copiar, fotocopiar, reproducir, traducir o convertir a cualquier medio impreso, electrónico o legible por máquina, enteramente o en parte, sin su previo consentimiento. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Lost in La Mancha

LOST IN LA MANCHA Available: C urrent Video : N/A Country: USA Distributor: Odeon Films Directors: Keith Fulton, Louis Pepe Running T ime: 89 min Rating: ON - AA AB - 14A "Making a film is essentially about two things: belief and momentum." Terry Gilliam Terry Gilliam first dreamt of making a film based on Don Quixote soon after completing the wonderfully zany THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN. At that time, he was suffering from what he has called "PMS" (Post Munchausen Syndrome), the fallout from the notorious 1989 production that cemented his reputation as a uncontrollable filmmaker. The proposed film would be called THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE and would tell the story of an arrogant ad executive (Johnny Depp, EDWARD SCISSORHANDS) who mysteriously stumbles into seventeenth-century Spain and meets Don Quixote (Jean Rochefort, READY TO WEAR). After a decade of development, production began in October 2000 - it was a fiasco. Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe's fascinating behind-the-scenes documentary, LOST IN LA MANCHA, follows Gilliam's doomed dream project from the final stages of pre- production through the first days of actual filming. Conveying a sense of QUIXOTE'S potential, LOST IN LA MANCHA is also a catalogue of crises: NATO jets buzzing over a seventeenth- century set; absent and injured star actors; fragile financing involving companies in England, Spain, France and Germany; and, underscoring the biblical proportions of it all, on the third day it rained — heavily. Watching Gilliam struggle with the problems of making a "studio-type" film with a relatively modest budget of $32 million, LOST IN LA MANCHA also serves as a compelling study of the clash between Hollywood's star-driven mode of production and a European model that serves the director. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Asides Magazine

2014|2015 SEASON Issue 5 TABLE OF Dear Friend, Queridos amigos: CONTENTS Welcome to Sidney Harman Bienvenidos al Sidney Harman Hall y a la producción Hall and to this evening’s de esta noche de El hombre de La Mancha. Personalmente, production of Man of La Mancha. 2 Title page The opening line of Don esta obra ocupa un espacio cálido pero enreversado en I have a personally warm and mi corazón al haber sido testigo de su nacimiento. Era 3 Musical Numbers complicated spot in my heart Quixote is as resonant in el año 1965 en la Casa de Opera Goodspeed en East for this show, since I was a Latino cultures as Dickens, Haddam, Connecticut. Estaban montando la premier 5 Cast witness to its birth. It was in 1965, at the Goodspeed Twain, or Austen might mundial, dirigida por Albert Marre. Se suponía que Opera House in East Haddam, CT. They were Albert iba a dirigir otra premier para ellos, la cual iba 7 About the Author mounting the world premiere, directed by Albert be in English literature. a presentarse en repertorio con La Mancha, pero Albert Marre. Now, Albert was supposed to direct another 10 Director’s Words world premiere for them, which was going to run In recognition of consiguió un trabajo importante en Hollywood y les recomendó a otro director: a mí. 12 The Impossible Musical in repertory with La Mancha, but he got a big job in Cervantes’ legacy, we at Hollywood, and he recommended another director. by Drew Lichtenberg That was me. STC want to extend our Así que fui a Goodspeed y dirigí la otra obra.