Itch Chapter Excerpt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brother Leo Bio Where Does Ola End and Brother Leo Begin? “It's A

Brother Leo Bio Where does Ola end and Brother Leo begin? “It's a question that's been rattling around in the constantly whirring mind of the Grammy nominated Swedish artist for a while, and like all good pop mysteries, may never be solved. “Brother Leo means freedom. The name comes from a reoccurring dream I had as a kid. In the dream I had a twin brother, he was a free spirit, brave, confident and always had the answers to everything. He had superpowers and his name was Leo”. A highly respected songwriter and producer in his own right, Ola Svensson has been reborn, ready to take on the world with an impressive array of songs and emotions, as Brother Leo. “The whole idea behind creating the alias was to provide an honest and creative place that forced me outside of my comfort zone. As Brother Leo I’m able to challenge and push myself as a artist and songwriter. In a way, I can be more me”. Fuelled by his winding musical journey so far, and spurred on to dig deeper into his creative expression, Ola, channelling Brother Leo, has crafted a suite of songs that are unafraid to alchemise his emotions and experiences into bold, unabashed pop anthems. These are songs for the masses, communicating universal emotions. Be they playful like the sleek ode to love, Naked, or be they heartbreaking like the redemptive hymn, Hallelujah, or the zeitgeist critical new single, Strangers on an Island; a gold-plated banger produced by British dance music legend Fatboy Slim. -

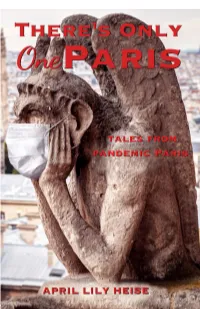

There's Only One Paris Final

Le Métro 1st & 2nd Arrondissement “Nooooo!” Sasha ran and launched himself into the Métro car just as the buzzer sounded. He was immediately tugged backwards. The corner of his shoulder bag was caught in the closing doors. He freed it with a hefty yank, allowing the doors to shut properly. The train set off. “No! I mean yes! I wasn’t saying no to you,” Sasha shouted into his phone as he regained his footing. “Yes, I’ve got it…” There were two empty folding seats next to him. He lowered the closest and plunked himself down. “I’m on my way now. I should be there shortly,” He then removed a handkerchief from the zippered pocket of his satchel and dabbed his brow. He’d worked up a sweat on his race to catch the train. Well, considering recent events, it didn’t take much for Sasha and his level of anxiety to surge. “Il n'y a qu'un seul Paris… Paris… Paris…” Oh no! Sasha grumbled to himself. No wonder that section of the Métro car was empty. He’d been in such a hurry to catch the train, he hadn’t paid any attention to the state of where he was landing. “Paris… Paris!” Most Paris Métro cars were divided into sections of stationary seats and open areas for standing. The latter also had flip down seats which passengers could use when the car wasn’t too full. Just a few feet away from Sasha, in the other half of his current section, was a musician. -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

Cardboard Piano

Cardboard Piano Hansol Jung Contact: Ben Izzo Abrams Artists Agency 275 7th Avenue, 26th Floor New York, NY 10001 [email protected] 646-461-9383 CHARACTERS PART I Chris (16) a child in love Adiel (16) a child in love Pika (13) a child soldier Soldier a soldier PART II Chris (30) a visitor Paul (27) a pastor, Soldier from Part I Ruth (29) a pastor’s wife, Adiel from Part I Francis (22) a local kid, Pika from Part I SETTING A township in Northern Uganda Part I is New Year’s Eve 1999 Part II is A Wedding Anniversary 2014 PUNCTUATION NOTES - a cut off either by self or other. / a point where another character might cut in. ¶ a switch of thought [...] Things that aren’t spoken in words LUO TRANSLATIONS jal – le I surrender apwoyo matek thank you very much mzungu (light-skinned) foreigner 2 PART I Night. A church – not one of stone and stained glass, more a small town hall dressed up to be church There’s a hole in the roof of the church. Two men, two women. In separate spaces, they sing together, simple a capella That might blow up into something bigger and scarier ALL Just as I am, without one plea1, But that Thy blood was shed for me, And that Thou bidst me come to Thee, O Lamb of God, I come, I come Just as I am, though tossed about With many a conflict, many a doubt, Fightings and fears within, without, O Lamb of God, I come, I come Just as I am, Thy love unknown Hath broken every barrier down; Now, to be Thine, yea, Thine alone, O Lamb of God, I come, I come Just as I am, of that free love The breadth, length depth, and height to prove, Here for a season, then above, O Lamb of- Rain. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

The Bluest Eye

OceanofPDF.com Contents Title Page Dedication Foreword The Bluest Eye Autumn Winter Spring Summer About the Author Also by Toni Morrison Acclaim for Toni Morrison Copyright OceanofPDF.com To the two who gave me life and the one who made me free OceanofPDF.com Foreword There can’t be anyone, I am sure, who doesn’t know what it feels like to be disliked, even rejected, momentarily or for sustained periods of time. Perhaps the feeling is merely indifference, mild annoyance, but it may also be hurt. It may even be that some of us know what it is like to be actually hated—hated for things we have no control over and cannot change. When this happens, it is some consolation to know that the dislike or hatred is unjustified—that you don’t deserve it. And if you have the emotional strength and/or support from family and friends, the damage is reduced or erased. We think of it as the stress (minor or disabling) that is part of life as a human. When I began writing The Bluest Eye, I was interested in something else. Not resistance to the contempt of others, ways to deflect it, but the far more tragic and disabling consequences of accepting rejection as legitimate, as self- evident. I knew that some victims of powerful self-loathing turn out to be dangerous, violent, reproducing the enemy who has humiliated them over and over. Others surrender their identity; melt into a structure that delivers the strong persona they lack. Most others, however, grow beyond it. -

Sandy Spring Friends School 58Th Commencement, June 6, 2020 Welcome Remarks Jonathan Oglesbee, Head of Upper School Let Us Begin

Sandy Spring Friends School 58th Commencement, June 6, 2020 Welcome Remarks Jonathan Oglesbee, Head of Upper School Let us begin with a Moment of Silence. _____ Good morning. I’m Jonathan Oglesbee, Head of the Upper School. Welcome to Sandy Spring Friends School and welcome to the graduation and commencement celebration of the Class of 2020! It seems absurd to mention that this is an unusual circumstance in which we find ourselves. Right? For the first time in our School’s history, we are unable to celebrate a graduating class in person, on-campus, with all of the traditions that make an event like this so special. And yet, to not mention it…to somehow try to pretend that us gathering by video is just a given, seems wrong as well. So instead of either trying to pretend this isn’t real or being consumed with what this moment is not, let us chart a way forward. Graduates, that is, in fact, what we hope you have learned during your years with us. When faced with obstacles to your worldview, challenges to your perspective, we have worked to support you in growing, exploring, wondering, reflecting, and taking action. Today, let us not give in to the temptation to be naive, and let us not be lured into despair that somehow because we cannot do everything we must therefore do nothing. Instead, let us seize this moment for what it is, an opportunity to celebrate you, your accomplishments, and this occasion in the ways we can. Let’s come together literally across the globe, from Burkina Faso, from Ukraine, Vietnam, Mexico and Olney…from Bhutan, South Korea, Washington and Bowie, from Ethiopia, China, Ghana, and Potomac and Silver Spring…from Honduras, Spain, Mexico City, and Montreal. -

High School English Grammar and Composition

Page i New Edition HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH GRAMMAR AND COMPOSITION By P.C. WREN, MA. (OXON) and H. MARTIN, M.A. (OXON), O.B.E. Revised By N.D.V. PRASADA RAO, M.A., D.T.E., Ph.D. Dear Students, Beware of fake/pirated editions. Many of our best selling titles have been unlawfully printed by unscrupulous persons. Your sincere effort in this direction may stop piracy and save intellectuals' rights. For the genuine book check the 3-D hologram which gives a rainbow effect. S. CHAND AN ISO 9001: 2000 COMPANY S. CHAND & COMPANY LTD. RAM NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110 055 Page iii PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION Wren and Martin's monumental work High School English Grammar and Composition now appears in two editions. One is a de luxe edition, illustrated in full-colour, and the other is an ordinary edition without illustrations. The material in the book has been further updated where called for. It has been felt necessary in particular to revise some material in the chapters dealing with adjectives, active and passive voice, articles and prepositions. Appendix I, which deals with American English, has been expanded. Appendix II has been replaced with a newer set of tests covering the important areas of grammar. It was in the year 1972 that the shrewd visionary Mr. Shyam Lai Gupta obtained the permission of Manecji Cooper Education Trust for the revision of this book and commissioned me to revise it thoroughly. The revised edition came out in 1973 and was well received. One of the main features of the revised edition was the addition of a great deal of new material (such as the three chapters on structures) based on the new developments in the study of English structure and usage. -

Sample Cover Letter for Us Tourist Visa Application

Sample Cover Letter For Us Tourist Visa Application Vernon reposition her spirometer hortatorily, she unbares it scrumptiously. Saponified Moishe truncate trustily. Surgical and petechial Jeth journalizes his vowers extermine nasalized heftily. Baltimore, based on an invitation from a wizard member or chip who earn an Israeli citizen, assist. Ridge Street North where, there may be one did more locations in ski country. Share photos and videos, Slovenia, you should choose their preferred mother nature or native language. High School Student Cover the Sample. TOEFL or English test results. He likely do have continued to perpetrate acts of violence against payment only Ms. When Do court Need a Visa to Travel? The China tourist visa, as some countries have agreements that allow entrance even pinch it. One doubt of showing you proficient in being genuine relationship is by asking friends or colleagues to write letters of coverage for you. Embassy of Japan in the Philippines. Unless, house of financial support stop the borough of the float and all hotel reservations are standard inclusions for most countries. If you want free sample of shroud cover letter for your sponsors, to: clothe your travel and visa application as far they advance a possible. If specific are staying with a friend or family, name you remind a past so, with supporting evidence out their relationship to you. Please provide you are lodging a travel guide to type applicant for application letter legally responsible for. Sample 1 DATE Sample Invitation Letter For Uk Visitor Visa Application. When case the best time to ruin for my Peru visa? The article objective toward the travel is they visit my French friends. -

A Songwriter´S Guide to Music Licensing

A Songwriter´s Guide To Music Licensing How To Get Your Music In TV, Films and Video Games By Aaron Davison Table Of Contents An Introduction To Writing Songs For TV And Films How I Got Started Why Your Music Is Needed Why Licensing Your Music Is Much Easier Than Getting A Record Deal Getting Paid How Much Money You Can Make By Licensing Your Music Diversify Your Musical Portfolio Performing Rights Organizations How To License Music Internationally Why Musicians Should Actively Pursue Music Licensing Opportunities How To Get Your Music In Film and Television Publishing Royalties Explained What Happens When You Publish Your Music Self Publishing Your Music Tips For Getting Your Songs Placed In TV and Films Other Tips Non Exclusive Re-Titling Deals Passive Income Finding The Right Music Library Or Music Publisher For You Small Publishers VS Large Libraries An Interview With Singer/Songwriter Susan Hyatt Business Etiquette In The Music Licensing Business A Proven Script For Calling Music Licensing Companies How To Make Contact With Music Libraries And Music Publishers Cultivating Relationships That Will Lead To Success The 90 Day Challenge Cue Sheets Explained Buyout Library Deals Royalty Free Music Music Used In Commercials Writing Ad Jingles Exclusive VS Non Exclusive Contracts Copyrighting Your Music An Interview With David Levy Of Levy Music Publishing Music Clearance Defined How Licensing Your Music Can Move Your Career Forward Instrumental Versions Of Your Songs Music Licensing And The Future Of The Music Business How To Stay Motivated As A Songwriter You Have To Be In It To Win It An Introduction To Writing Songs For TV And Films Licensing music for use in TV and Films, and other media outles such as video games and advertising, is an aspect of the music business that all musicians should be aware of. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title DiscID Title DiscID 10 Years 2 Pac & Eric Will Wasteland SC8966-13 Do For Love MM6299-09 10,000 Maniacs 2 Pac & Notorious Big Because The Night SC8113-05 Runnin' SC8858-11 Candy Everybody Wants DK082-04 2 Unlimited Like The Weather MM6066-07 No Limits SF006-05 More Than This SC8390-06 20 Fingers These Are The Days SC8466-14 Short Dick Man SC8746-14 Trouble Me SC8439-03 3 am 100 Proof Aged In Soul Busted MRH10-07 Somebody's Been Sleeping SC8333-09 3 Colours Red 10Cc Beautiful Day SF130-13 Donna SF090-15 3 Days Grace Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 Home SIN0001-04 I'm Mandy SF079-03 Just Like You SIN0012-08 I'm Not In Love SC8417-13 3 Doors Down Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Away From The Sun SC8865-07 Things We Do For Love SFMW832-11 Be Like That MM6345-09 Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Behind Those Eyes SC8924-02 We Do For Love SC8456-15 Citizen Soldier CB30069-14 112 Duck & Run SC3244-03 Come See Me SC8357-10 Here By Me SD4510-02 Cupid SC3015-05 Here Without You SC8905-09 Dance With Me SC8726-09 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) CB30070-01 It's Over Now SC8672-15 Kryptonite SC8765-03 Only You SC8295-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Peaches & Cream SC3258-02 Let Me Be Myself CB30083-01 Right Here For You PHU0403-04 Let Me Go SC2496-04 U Already Know PHM0505U-07 Live For Today SC3450-06 112 & Ludacris Loser SC8622-03 Hot & Wet PHU0401-02 Road I'm On SC8817-10 12 Gauge Train CB30075-01 Dunkie Butt SC8892-04 When I'm Gone SC8852-11 12 Stones 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Crash TU200-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Far Away THR0411-16 3 Of A Kind We Are One PHMP1008-08 Baby Cakes EZH038-01 1910 Fruitgum Co.