The Global Art Cinema of Jim Jarmusch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the Operating System Print//Document

IN STILL ROOMS CONSTANTINE JONES the operating system print//document IN STILL ROOMS ISBN: 978-1-946031-86-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020933062 copyright © 2020 by Constantine Jones edited and designed by ELÆ [Lynne DeSilva-Johnson] is released under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non Commercial, No Derivatives) License: its reproduction is encouraged for those who otherwise could not aff ord its purchase in the case of academic, personal, and other creative usage from which no profi t will accrue. Complete rules and restrictions are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ For additional questions regarding reproduction, quotation, or to request a pdf for review contact [email protected] Th is text was set in avenir, minion pro, europa, and OCR standard. Books from Th e Operating System are distributed to the trade via Ingram, with additional production by Spencer Printing, in Honesdale, PA, in the USA. the operating system www.theoperatingsystem.org [email protected] IN STILL ROOMS for my mother & her mother & all the saints Aιωνία η mνήμη — “Eternal be their memory” Greek Orthodox hymn for the dead I N S I D E Dramatis Personae 13 OVERTURE Chorus 14 ACT I Heirloom 17 Chorus 73 Kairos 75 ACT II Mnemosynon 83 Chorus 110 Nostos 113 CODA Memory Eternal 121 * Gratitude Pages 137 Q&A—A Close-Quarters Epic 143 Bio 148 D R A M A T I S P E R S O N A E CHORUS of Southern ghosts in the house ELENI WARREN 35. Mother of twins Effie & Jr.; younger twin sister of Evan Warren EVAN WARREN 35. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

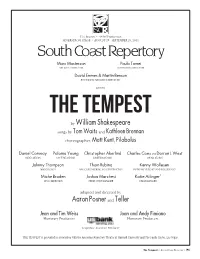

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Liste Dvd Consult

titre réalisateur année durée cote Amour est à réinventer (L') * 2003 1 h 46 C 52 Animated soviet propaganda . 1 , Les impérialistes américains * 1933-2006 1 h 46 C 58 Animated soviet propaganda . 2 , Les barbares facistes * 1941-2006 2 h 16 C 56 Animated soviet propaganda . 3 , Les requins capitalistes * 1925-2006 1 h 54 C 59 Animated soviet propaganda . 4 , Vers un avenir brillant, le communisme * 1924-2006 1 h 54 C 57 Animatix : une sélection des meilleurs courts-métrages d'animation française. * 2004 57 min. C 60 Animatrix * 2003 1 h 29 C 62 Anime story * 1990-2002 3 h C 61 Au cœur de la nuit = Dead of night * 1945 1 h 44 C 499 Autour du père : 3 courts métrages * 2003-2004 1 h 40 C 99 Avant-garde 1927-1937, surréalisme et expérimentation dans le cinéma belge * 1927-1937 1 h 30 C 100 (dvd 1&2) Best of 2002 * 2002 1 h 12 C 208 Caméra stylo. Vol. 1 * 2001-2005 2 h 25 C 322 Cinéma différent = Different cinema . 1 * 2005 1 h 30 C 461 Cinéma documentaire (Le) * 2003 2 h 58 C 462 Documentaire animé (Le). 1, C'est la politique qui fait l'histoire : 9 films * 2003-2012 1 h 26 C 2982 Du court au long. Vol. 1 * 1973-1986 1 h 52 C 693 Fellini au travail * 1960-1975 3 h 20 C 786 (dvd 1&2) Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. 01 * 1947-1984 2 h 40 C 3176 Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. -

AF Yo Bill Murray 051016.Indd

Primera edición, noviembre 2016 © Marta Jiménez © Ilustraciones: sus autores © Diseño de cubierta e ilustraciones en Momentos Murray: Pedro Peinado © Diseño de colección: Pedro Peinado www.pedropeinado.com Edición de Antonio de Egipto y Marga Suárez www.estonoesuntipo.com Bandaàparte Editores www.bandaaparteeditores.com ISBN 978-84-944086-8-7 Depósito Legal CO-1591-2016 Este libro está bajo Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento – NoComercial – SinObraDerivada (by-nc-nd): No se permite un uso comercial de la obra original ni la generación de obras derivadas. +info: www.es.creativecommons.org Impresión: Gráficas La Paz. www.graficaslapaz.com El papel empleado para la impresión de este libro proviene de bosques gestionados de manera sostenible, desde el punto de vista medioambiental, económico y social. Impreso en España A mi padre y a mi madre, que no recuerdan dónde han visto a Bill Murray RZA: Tú eres Bill Murray. Bill Murray: Lo sé, pero no se lo digas a nadie. GZA: ¿Qué quieres decir con que no lo cuente, Bill Murray? La gente vendrá, te verá, eres Bill Murray, es obvio, a menos que uses un disfraz o algo. Bill Murray: Estoy disfrazado. GZA: Maldición, eso es terrible, amigo. (Coffee and Cigarettes. Jim Jarmusch, 2004) THE EVERYDAY MAN por Javier del Pino Un humorista muy conocido suele decir que hay dos tipos de có- micos: los que tienen gracia y los que tienen que trabajar para tener gracia. Lo dice con resignación, porque pertenece a la segunda cate- goría. Nada le hubiera gustado más que haber nacido con las carac- terísticas indescriptibles que definen a ese minúsculo grupo de per- sonas que, en un universo tan multitudinario, tienen la pintoresca virtud de expresar sentimientos o provocar reacciones sin decir nada y sin hacer nada. -

Les Événements Au Cinéma Du Tnb Juillet 2019

LES ÉVÉNEMENTS AU CINÉMA DU TNB JUILLET 2019 JIM JARMUSCH SOPHIE LALY MÉLISSA PLAZA FÊTE DU CINÉMA ... Théâtre National de Bretagne Direction Arthur Nauzyciel 1 rue Saint-Hélier 35000 Rennes T-N-B.fr RÉTROSPECTIVE 03 07 — 20 07 © Sara Driver © Sara 2 (RE)DÉCOUVREZ LES FILMS DE Cette rétrospective propose de redécouvrir JIM JARMUSCH ses 6 premiers films : de Permanent Vacation, À L'OCCASION DE LA SORTIE EN VERSIONS film de fin d’école au charme fou, à Dead Man RESTAURÉES DES 6 PREMIERS FILMS relecture romantique du western ; de Stranger DE JIM JARMUSCH Than Paradise, Caméra d’or au festival de Cannes 1984, à Night on Earth, flâneries Retour sur la carrière exemplaire de Jim en taxi dans 5 grandes villes ; de Down by Law Jarmusch, cinéaste rock'n'roll par excellence, et ses pieds nickelés en cavale à Mystery Train marqué par la scène underground de la fin hanté par le fantôme d'Elvis. L’univers de Jim des années 70 dandy iconoclaste n'ayant Jarmusch c’est aussi une famille d’acteurs jamais dévié de ses convictions, resté attaché : John Lurie, Roberto Benigni, Isaach de aux mêmes passions et figures tutélaires Bankolé, Iggy Pop, Tom Waits, Eszter Balint, d’une Amérique mythique. D’un style Steve Buscemi que l’on retrouve dans The flottant et imperturbable mais aucunement Dead Don’t Die, son dernier film en salle. sententieux ni prétentieux, ses films Le cinéma de Jim Jarmusch et son éternelle possèdent une patte reconnaissable dès jeunesse sont à retrouver intactes grâce ses débuts : un minimalisme laconique, à des copies numériques restaurées un détachement souverain mais humaniste. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis MUSIK IST STENOGRAPHIE DER GEFÜHLE. Ein Versuch der Untersuchung der durch Musik und musikalischer Untermalung hervorgerufenen bzw. gestützten emotionalen Kommunikation in Filmen verfasst von / submitted by Katharina Köhle, bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 841 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Fritz (Friedrich) Hausjell INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINFÜHRUNG _____________________________________________ S. 4 2. THEMENGRUNDLAGEN _____________________________________ S. 6 2.1. FILM ..................................................................................................................... S. 6 2.1.1. Definition ............................................................................................... S. 6 2.1.2. Historischer Abriss ................................................................................. S. 14 2.1.3. Filmtheorie .............................................................................................. S. 18 2.2. MUSIK ................................................................................................................. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Politics Isn't Everything

Vol. 9 march 2017 — issue 3 iNSIDE: TOWNHALL TO NO ONE - POLITICS ISN’T EVERYTHING - COLD - why aren’t millennials eating pho - still drinking - BEST PUNK ALBUM EVER?? - ASK CREEPY HORSE - LOST BOYS OF THE RIGHT - misjumped - record reviews - concert calendar Town hall to no one Recently I was invited to attend a town hall meeting for our local representative to Congress, Rep. Bill Flores. In this day and age, you definitely want to have access to the person your district voted to send to 979Represent is a local magazine Washington and represent the interests of your home for the discerning dirtbag. area. 100 or so people turned out, submitted questions, gave passionate testimonials, aired grievances, ex- pressed outrage, even gave praise to Flores for a certain Editorial bored stance (though that was brief). Gay, straight, trans, white, other, Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, profession- Kelly Minnis - Kevin Still al, student, retired...a cross-section of the district’s diverse populace attended. Local police kept everything low key, local media showed to document the process. Art Splendidness Ivory is white, coal is black, water is wet...who cares, Katie Killer - Wonko The Sane right? This sort of thing happens all the time all over the country so what was so special about this event? Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us It was a townhall meeting with our congress- man...without the actual congressman in attendance. HENRY CLAYMORE - CREEPY HORSE - TIMOTHY MEATBALL He decided not to participate and instead flew to Mar-A- DANGER - MIKE L. DOWNEY - Jorge goyco - TODD HANSEN Lago to pull on Daddy Trump’s shirttail to beg of some EZEKIAL HENRY - Rented mule - HENRY ROWE - STARKNESS of the Orange Julius’s attention.