Learning Factors in Substance Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Juan County Adult Drug Court Participant Handbook

Participant Manual SEVENTH DISTRICT ADULT DRUG COURT MONTICELLO, UTAH Updated January 2018 Subject to Change 1 2 Welcome to the San Juan County Adult Drug Court This Handbook is designed to introduce you to the San Juan County Drug Court program, answer your questions and provide overall information about the Drug Court Program. As a participant, you will be expected to follow the instructions given in Drug Court by the Judge and comply with the treatment plan developed for you by the treatment team. If you are reading this Handbook it means that we are confident that Drug Court will help you to learn how to make successful choices free of the influence of drugs or alcohol. 3 Table of Contents Welcome to the San Juan County Adult Drug Court ...................................................................... 3 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Drug Court Team ........................................................................................................................... 7 Judge’s Role ........................................................................................................................... 7 San Juan County Attorney’s Role (Prosecutor) ....................................................................... 8 Defense Attorney Role (Your Attorney) ................................................................................... 8 Probation Officer’s Role ......................................................................................................... -

The Impact of NMR and MRI

WELLCOME WITNESSES TO TWENTIETH CENTURY MEDICINE _____________________________________________________________________________ MAKING THE HUMAN BODY TRANSPARENT: THE IMPACT OF NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING _________________________________________________ RESEARCH IN GENERAL PRACTICE __________________________________ DRUGS IN PSYCHIATRIC PRACTICE ______________________ THE MRC COMMON COLD UNIT ____________________________________ WITNESS SEMINAR TRANSCRIPTS EDITED BY: E M TANSEY D A CHRISTIE L A REYNOLDS Volume Two – September 1998 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 1998 First published by the Wellcome Trust, 1998 Occasional Publication no. 6, 1998 The Wellcome Trust is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 186983 539 1 All volumes are freely available online at www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Tansey E M, Christie D A, Reynolds L A. (eds) (1998) Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 2. London: Wellcome Trust. Key Front cover photographs, L to R from the top: Professor Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, speaking (NMR) Professor Robert Steiner, Professor Sir Martin Wood, Professor Sir Rex Richards (NMR) Dr Alan Broadhurst, Dr David Healy (Psy) Dr James Lovelock, Mrs Betty Porterfield (CCU) Professor Alec Jenner (Psy) Professor David Hannay (GPs) Dr Donna Chaproniere (CCU) Professor Merton Sandler (Psy) Professor George Radda (NMR) Mr Keith (Tom) Thompson (CCU) Back cover photographs, L to R, from the top: Professor Hannah Steinberg, Professor -

Narcotics Dangerous Drugs

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Ir I - This microfiche was produced from documents received for inclusion in the NCJRS data base. Since NCJRS cannot exercise control ovcr the physical condition of the documents submitted, the individual frame quality will vary. The resolution chart on this frame may be used to evaluate the document quality. 1.0 1.1 REFERENCE BOOK -- -- 111111.8 \\\\\1.25 111111.4 \\\\\1.6 NARCOTICS AND MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL" BUREAU '.F STANDARDS-\963-A DANGEROUS DRUGS Microfilming procedures used to create this fiche comply with i ! the standards set forth in 41CFR 101·11.504 " Compiled by Points of view or opinions stated in this document an I those of the 3uthorlsj and do not represent the official GLENDALE CRIME LABORATORY position or policies of the U.S. Department o,f Justice. 5909 N. Milwaukee River Parkway Glendale, Wisconsin 53209 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION" o NATIONAL CRiMINAL JUSTICE REFERENCE SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20531 ·00 Q a PRICE $'1 12/9/ 75 .,',' J INTRODUCTION This compilation has been taken from many sources primarily for '- use by participants in seminars and workshops on "Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs" conducted by the Glendale Crime Laboratory and for users of the Glendale Crime Laboratory Automated Teaching System programs on "Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs." This com pilation is not meant to be all inclusive. Your comments, criticisms and notation of errors would 'De ap preciated. Materials for inclusion in future revision would be ap preciated. -

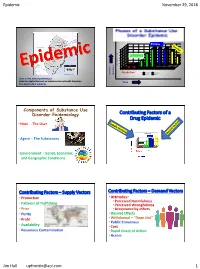

Epidemic November 29, 2018 Jim Hall [email protected] 1

Epidemic November 29, 2018 Phases of a Drug Epidemic Plateau 35 30 25 Expansion 20 15 10 Users & Problems X Users 1000 & Problems X 5 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Yr 10 Incubation Incubation Expansion & Problems # of Users Plateau Decline James N. Hall, Senior Epidemiologist Center for Applied Research on Substance Use and Health Disparities Time Nova Southeastern University Components of Substance Use Disorder Epidemiology Contributing Factors of a Drug Epidemic • Host - The User • Agent – The Substances • Environment - Social, Economic, and Geographic Conditions Contributing Factors – Supply Vectors Contributing Factors – Demand Vectors • Production •Attitudes: • Perceived Harmfulness • Patterns of Trafficking • Perceived Wrongfulness • Price • Acceptance by others • Purity • Desired Effects • Profit • Withdrawal – “Dope Sick” • Public Consensus • Availability • Cost • Poisonous Contamination • Rapid Onset of Action • Access Jim Hall [email protected] 1 Epidemic November 29, 2018 Reoccurring Patterns of Opioid Epidemics: 1880 - 2018 Opioids 1990 - 2018 Reoccurring Heroin & Fentanyls Patterns of 1955 - 1970 Rx Opioids Substance Use 1880 - 1900 Disorder Heroin Epidemics Morphine & Heroin 1880 – 2018 # # of users and level of consequences 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 The Morphine Molecule DEFINITION OF OPIOID • Binding to and activating “Similar to opium” the opioid μ receptors in the brain and spine Morphine and similar drugs derived from opium • Principal -

VII. MEDICATIONS to AVOID (Do Not Take These Medications)

ATTACHMENT #1 TO THE DOUGLAS COUNTY DUI/Drug COURT HANDBOOK VII. MEDICATIONS TO AVOID (Do not take these medications) WARNING: THIS LIST IS NOT INTENDED TO BE ALL INCLUSIVE. ALL MEDICATIONS MUST BE CLEARED THROUGH YOUR COUNSELOR PRIOR TO TAKING. Note: Drug Name® = Brand Name A Actiq® (fentanyl) Adipex-P® (phentermine) Adderall® (dextroamphetamine + amphetamine) alcohol (ethanol, ethyl alcohol) or anything containing ethyl alcohol including “Alcohol-Free” beer. Many over-the-counter liquid preparations such as cough syrups, cold medications, mouthwash, body washes or gels, etc. may contain alcohol and may produce a positive EtG (alcohol) urine drug screen. It is YOUR responsibility to read the labels on these preparations, or ask a pharmacist to make sure the products you use do not contain alcohol. alprazolam (Xanax®) ALURATE Ambien® (zolpidem) amphetamine or any product containing amphetamine or any of its derivatives, such as dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine®), benzphetamine (Didrex®), methamphetamine (Desoxyn®, speed, meth, ice, crystal, etc.), DOM, de- or di-methoxyamphetamine and others. AMYTAL NA. A.P.C. W/DEMEROL APPEDRINE ATARAX Ativan® (lorazepam) atropine or any product containing atropine AtroPen® or any other product containing atropine B B.A.C. BANCAP HC barbiturates, including but not limited to butabarbital (Butisol®), butalbital (Fiorinal® and others), mephobarbital (Mebaral®), phenobarbital (Nembutal®, yellow jackets, (Donnatal®), secobarbital (Seconal®, red devils, Xmas trees, rainbows), thiopental (Pentothal®) and any other -

A Mixed Methods Study of Antidepressant Use and Withdrawal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Collateral Damage: A Mixed Methods Study to Investigate the Use and Withdrawal of Antidepressants Within a Naturalistic Population By Susan Thrasher A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Psychology 2010 ii Abstract The use of modern antidepressants has flourished over the past few decades with the modern attribution of affective disorders such as depression to biomedical causation. However, recent re-examination of clinical trials has raised questions regarding antidepressant drug efficacy, and issues around side effects and dependency are prevalent. In spite of this, as many as 10% of us may be taking these medications (Szabo, 2009). This study examines responses to an anonymous online survey about antidepressant use and withdrawal. Participants included 176 current users, 181 currently withdrawing, 108 ex-users, and a control group of 44 participants who had never used antidepressants. Participant groups were compared quantitatively regarding attitude towards antidepressants use and perceived value, effect on well-being and mood, symptoms and side effects, and their perceived changes in themselves on and off the drugs. Participants were also given the opportunity to include spontaneous comments at the end of the survey which were analysed thematically. Key findings include: 1) Antidepressant users -

2014 NSDUH Field Interviewer Manual September 2013 I Table of Contents Table of Contents (Continued)

2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Field Interviewer Computer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 Field Interviewer:__________________________________________ FI ID No:__________________ 2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 Research Triangle Institute MISSION To improve the human condition by turning knowledge into practice. VISION To be the world’s leading independent research organization, recognized for solving critical social and scientific problems. VALUES Integrity - We perform with the highest ethical standards of individual and group honesty. We communicate openly and realistically with each other and with our clients. Excellence - We strive to deliver results with exceptional quality and value. Innovation - We encourage multidisciplinary collaboration, creativity and independent thinking in everything we do. Respect for the Individual - We treat one another fairly, with dignity and equity. We support each other to develop to our full potential. Respect for RTI - We recognize that the strength of RTI International lies in our commitment, collectively and individually, to RTI’s vision, mission, values, strategies and practices. Our commitment to the Institute is the foundation for all other organizational commitments. -

Organization and Development of a Computerized Drug-Drug Interaction File

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 1972 Organization and Development of a Computerized Drug-Drug Interaction File Charles Daniel Mahoney University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Mahoney, Charles Daniel, "Organization and Development of a Computerized Drug-Drug Interaction File" (1972). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 203. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/203 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ( ORGANIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF A COMPUTERIZED DRUG-DRUG INTERACTION FILE BY CHARLES DANIEL MAHONEY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE ( REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN PHARMACY UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 1972 ( ( MASTEH OF SCIENCE THESIS OF CHAHLES DANIEL MAHONEY Approved: Thesis Committee: ( Chairman fl(C , ~ ---·----''-'- Dean of the Graduate School UNIVERSITY OF HIIODE ISLAND 1972 ( ( TITLE ABSTRACT COMPUTERIZED DHUG-DRUG INTERACTION FILE ( ii ABS'J'.RACT ( The project was designed to organiz e and develop a comput erized drug-drug intera ction file. The methodology for the organ ization, storage and retrieval of drug-drug interaction information i s discussed. In order to accor.nplish this objective several requirements were met. Th8y are a s folimvs: (1) Seleciion and evaluation of clin ically significant drug-drug interactions from the scientific literature, (2) C reation of a computerized data bank for drug-drug interactions, and (3) Design and developme nt of a computerized printout which reports the i nformation in concise s ummaries. -

CNS-Targeting Pharmacological Interventions for the Metabolic Syndrome

CNS-targeting pharmacological interventions for the metabolic syndrome Kerstin Stemmer, … , Paul T. Pfluger, Matthias H. Tschöp J Clin Invest. 2019;129(10):4058-4071. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129195. Review Series The metabolic syndrome (MetS) encompasses medical conditions such as obesity, hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia that are major drivers for the ever-increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer. At the core of clinical strategies against the MetS is weight loss, induced by bariatric surgery, lifestyle changes based on calorie reduction and exercise, or pharmacology. This Review summarizes the past, current, and future efforts of targeting the MetS by pharmacological agents. Major emphasis is given to drugs that target the CNS as a key denominator for obesity and its comorbid sequelae. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/129195/pdf REVIEW SERIES: MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE METABOLIC SYNDROME The Journal of Clinical Investigation Series Editor: Philipp E. Scherer CNS-targeting pharmacological interventions for the metabolic syndrome Kerstin Stemmer,1,2 Timo D. Müller,1,2 Richard D. DiMarchi,3 Paul T. Pfluger,1,2 and Matthias H. Tschöp1,2,4 1Institute for Diabetes and Obesity, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Neuherberg, Germany. 2German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), Neuherberg, Germany. 3Department of Chemistry, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, USA. 4Division of Metabolic Diseases, Department of Medicine, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany. The metabolic syndrome (MetS) encompasses medical conditions such as obesity, hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia that are major drivers for the ever-increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer. -

The Amphetamine Years: a Study of the Medical Applications and Extramedical Consumption of Psychostimulant Drugs in the Postwar United States, 1945-1980

THE AMPHETAMINE YEARS: A STUDY OF THE MEDICAL APPLICATIONS AND EXTRAMEDICAL CONSUMPTION OF PSYCHOSTIMULANT DRUGS IN THE POSTWAR UNITED STATES, 1945-1980 A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Nathan William Moon In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History and Sociology of Technology and Science Georgia Institute of Technology December 2009 Copyright © Nathan William Moon 2009 THE AMPHETAMINE YEARS: A STUDY OF THE MEDICAL APPLICATIONS AND EXTRAMEDICAL CONSUMPTION OF PSYCHOSTIMULANT DRUGS IN THE POSTWAR UNITED STATES, 1945-1980 Approved by: Dr. Andrea Tone, Advisor Dr. Steven Usselman Social Studies of Medicine and School of History, Technology & Department of History Society McGill University Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Douglas Flamming Dr. John Krige School of History, Technology & School of History, Technology & Society Society Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Jonathan Metzl Date Approved: November 2, 2009 Women’s Studies Program and Department of Psychiatry University of Michigan For Michele ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Even if it has but a single author, a dissertation is the product of many people. This one is no exception, and I am extremely grateful to all of the people who made mine a reality. First, I wish to extend my sincere thanks to my advisor Andrea Tone. She has been a model mentor in every way imaginable. Andrea guided me through the scholarship and shepherded this dissertation project with the utmost diligence and care. Although she had many other responsibilities, Andrea never failed to make time for me. She read my chapters and conference paper proposals, attended my talks, and introduced me to leading scholars in our field. -

Historical Trends and Current Patterns of Methamphetamine Use in the U.S

Historical Trends and Current Patterns of Methamphetamine Use in the U.S. and 3 NDEWS Sentinel Sites Los Atlanta Angeles Texas Cocaine Pharmaceutical Stimulants Methamphetamine Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics 1880 – 2019 Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics:1880 - 2018 1975 - 2018 Cocaine 1880 - 1920 # of users and level of consequences level and # users of 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics:1880 - 2018 Pharmaceutical Stimulants 1929 - 1970 1994 - 2018 # of users and level of consequences level and # users of 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics:1880 - 2018 Illicit Methamphetamine 1970 - 1995 2008 - 2018 # of users and level of consequences level and # users of 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics: 1880 - 2018 Cocaine Pharmaceutical Stimulants Methamphetamine # of users and level of consequences level and # users of Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics:1880 - 2018 1975 - 2018 Cocaine 1880 - 1920 # of users and level of consequences level and # users of 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 Reoccurring Patterns of Stimulant Epidemics:1880 - 2018 Pharmaceutical Stimulants 1929 - 1970 1994 - 2018 # of users and level of consequences level and # users of 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2018 Pharmaceutical Amphetamines • 1887 – First produced in Germany • 1919 – Japan makes more powerful version: methamphetamine • 1929-1945 - First US Epidemic generated by pharmaceutical industry and medical profession • 1933 - Smith, Kline and French (SKF) patented amphetamine SKF marketed it as the Benzedrine Inhaler (325 mg of oily amphetamine base). -

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1982 Questionnaire

National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1982 United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Drug Abuse Data Collection Instrument is sponsored by Terms of Use These data are distributed under the following terms of use. By continuing past this page, you signify your agreement to comply with the requirements as stated below: Privacy of Research Subjects Any intentional identification of a research subject (whether an individual or an organization) or unauthorized disclosure of his or her confidential information violates the promise of confidentiality given to the providers of the information. Disclosure of confidential information may also be punishable under federal law. Therefore, users of data agree: To use these datasets solely for research or statistical purposes and not for re- identification of specific research subjects. To make no use of the identity of any research subject discovered inadvertently and to report any such discovery to CBHSQ and SAMHDA (samhda- [email protected]) Citing Data You agree to reference the recommended bibliographic citation in any of your publications that use SAMHDA data. Authors of publications that use SAMHDA data are required to send citations of their published works for inclusion in a database of related publications. Disclaimer You acknowledge that SAMHSA will bear no responsibility for your use of the data or for your interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Violations If CBHSQ determines that this terms of use agreement has been violated, then possible sanctions could include: Report of the violation to the Research Integrity Officer, Institutional Review Board, or Human Subjects Review Committee of the user's institution.