Protocol for a Systematic Literature Review and Network Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dosing Time Matters

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/570119; this version posted March 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Dosing Time Matters 1 2,3 4,5,6 1* Marc D. Ruben , David F. Smith , Garret A. FitzGerald , and John B. Hogenesch 1 Division of Human Genetics, Center for Chronobiology, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, 240 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH, 45229 2 Divisions of Pediatric Otolaryngology and Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229 3 Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, 231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH, 45267 4 Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics, at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA 5 Department of Medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA 6 Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT), at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Abstract Trainees in medicine are taught to diagnose and administer treatment as needed; time-of-day is rarely considered. Yet accumulating evidence shows that ~half of human genes and physiologic functions follow daily rhythms. Circadian medicine aims to incorporate knowledge of these rhythms to enhance diagnosis and treatment. -

Nystatin Ofloxacin Orciprenaline Sulfate

JP XV Ultraviolet-visible Reference Spectra 1619 Nystatin A solution prepared as follows: To 10 mg add 50.25 mL of a mixture of diluted methanol (4 in 5) and sodium hydroxide TS (200:1), dissolve by warming at not exceeding 509C,andadddilutedmethanol(4in5)tomake500 mL. Ofloxacin Asolutionin0.1mol/LhydrochloricacidTS(1in150,000) Orciprenaline Sulfate A solution in 0.01 mol/L hydrochloric acid TS (1 in 10,000) 1620 Ultraviolet-visible Reference Spectra JP XV Oxazolam A solution in ethanol (95) (1 in 100,000) Oxethazaine A solution in ethanol (95) (1 in 2500) Oxybuprocaine Hydrochloride An aqueous solution (1 in 100,000) JP XV Ultraviolet-visible Reference Spectra 1621 Oxycodone Hydrochloride Hydrate An aqueous solution (1 in 10,000) Oxymetholone A solution prepared as follows: To 5 mL of a solution in methanol (1 in 5000) add 5 mL of sodium hydroxide-methanol TS and methanol to make 50 mL. Oxytetracycline Hydrochloride Asolutionin0.1mol/LhydrochloricacidTS(1in50,000) 1622 Ultraviolet-visible Reference Spectra JP XV Oxytocin An aqueous solution (1 in 2000) Penbutolol Sulfate A solution in methanol (1 in 10,000) Pentazocine A solution in 0.01 mol/L hydrochloric acid TS (1 in 10,000) JP XV Ultraviolet-visible Reference Spectra 1623 Peplomycin Sulfate Asolutionpreparedasfollows:To4mgadd5mL of copper (II) sulfate TS, and dissolve in water to make 100 mL. Perphenazine 1 Asolutionin0.1mol/LhydrochloricacidTS(1in200,000) Perphenazine 2 A solution obtained by adding 10 mL of water to 10 mL of the solution for Perphenazine 1 1624 Ultraviolet-visible -

Clenbuterol Elisa Kit Instructions Product #101219 & 101216 Forensic Use Only

Neogen Corporation 944 Nandino Blvd., Lexington KY 40511 USA 800/477-8201 USA/Canada | 859/254-1221 Fax: 859/255-5532 | E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.neogen.com/Toxicology CLENBUTEROL ELISA KIT INSTRUCTIONS PRODUCT #101219 & 101216 FORENSIC USE ONLY INTENDED USE: For the determination of trace quantities of Clenbuterol and/or other metabolites in human urine, blood, oral fluid. DESCRIPTION Neogen Corporation’s Clenbuterol ELISA (Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay) test kit is a qualitative one-step kit designed for use as a screening device for the detection of drugs and/or their metabolites. The kit was designed for screening purposes and is intended for forensic use only. It is recommended that all suspect samples be confirmed by a quantitative method such as gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). ASSAY PRINCIPLES Neogen Corporation’s test kit operates on the basis of competition between the drug or its metabolite in the sample and the drug- enzyme conjugate for a limited number of antibody binding sites. First, the sample or control is added to the microplate. Next, the diluted drug-enzyme conjugate is added and the mixture is incubated at room temperature. During this incubation, the drug in the sample or the drug-enzyme conjugate binds to antibody immobilized in the microplate wells. After incubation, the plate is washed 3 times to remove any unbound sample or drug-enzyme conjugate. The presence of bound drug-enzyme conjugate is recognized by the addition of K-Blue® Substrate (TMB). After a 30 minute substrate incubation, the reaction is halted with the addition of Red Stop Solution. -

Diamandis Thesis

!"!#$ CHEMICAL GENETIC INTERROGATION OF NEURAL STEM CELLS: PHENOTYPE AND FUNCTION OF NEUROTRANSMITTER PATHWAYS IN NORMAL AND BRAIN TUMOUR INITIATING NEURAL PRECUSOR CELLS by Phedias Diamandis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto © Copyright by Phedias Diamandis 2010 Phenotype and Function of Neurotransmitter Pathways in Normal and Brain Tumor Initiating Neural Precursor Cells Phedias Diamandis Doctor of Philosophy Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto 2010 &'(!)&*!% The identification of self-renewing and multipotent neural stem cells (NSCs) in the mammalian brain brings promise for the treatment of neurological diseases and has yielded new insight into brain cancer. The complete repertoire of signaling pathways that governs these cells however remains largely uncharacterized. This thesis describes how chemical genetic approaches can be used to probe and better define the operational circuitry of the NSC. I describe the development of a small molecule chemical genetic screen of NSCs that uncovered an unappreciated precursor role of a number of neurotransmitter pathways commonly thought to operate primarily in the mature central nervous system (CNS). Given the similarities between stem cells and cancer, I then translated this knowledge to demonstrate that these neurotransmitter regulatory effects are also conserved within cultures of cancer stem cells. I then provide experimental and epidemiologically support for this hypothesis and suggest that neurotransmitter signals may also regulate the expansion of precursor cells that drive tumor growth in the brain. Specifically, I first evaluate the effects of neurochemicals in mouse models of brain tumors. I then outline a retrospective meta-analysis of brain tumor incidence rates in psychiatric patients presumed to be chronically taking neuromodulators similar to those identified in the initial screen. -

Lamas for COPD Systematic Review

Comparative safety and effectiveness of inhaled long -acting agents (corticosteroids, beta agonists, anticholinergics) for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Comprehensive Research Plan: Systematic Review Unit April 4th, 2014 Andrea C. Tricco, PhD1 and Sharon E. Straus, MD, MSc1,2 30 Bond Street, Toronto ON, M5B 1W8 www.odprn.ca [email protected] Background Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by airflow limitation in the lungs [1]. COPD is commonly assessed by clinical examination and spirometry. Important indicators considered in the diagnosis of COPD include age over 40 years and any of the following: 1) progressive and persistent dyspnea that worsens with exercise, 2) chronic cough, 3) chronic sputum production, 4) history of exposure to smoke from tobacco or cooking, occupational dusts and chemicals, and 5) family history of COPD [1]. COPD causes significant burden of illness, reduced quality of life, and premature death [2]. Symptoms include chronic cough, sputum production, and dyspnea [3]. The global prevalence of COPD has been estimated at 7.6% using data from a systematic review including 28 countries [4]. However, this is likely a conservative estimate, due to under-reporting and under-diagnosis. The prevalence and burden of COPD is rising due the greater proportion of elderly people in the population [1]. It is estimated that COPD will be the third-leading cause of death by 2020 [5]. The treatment of COPD usually involves reducing exposure (e.g., smoking cessation, occupation modifications), increasing exercise, and implementing appropriate pharmacologic therapy [1]. The most common drug classes are beta2-agonists, anticholinergics, and methylxanthines. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and systemic corticosteroids are often useful for acute exacerbations. -

100 Storage Condition=50 C/Ambrh

USOO595.5058A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: S.9SS,0589 9 Jager et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 21,9 1999 54). STABILIZED MEDICINAL AEROSOL 56) References Cited SOLUTION FORMULATIONS CONTAINING U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS IPRATROPIUM BROMIDE a 5,118,494 6/1992 Schultz et al. ............................ 424/45 75 Inventors: Paul Donald Jager, Waterbury; Mark 5,190,029 3/1993 Byron et al. ... ... 128/200.14 James Kontny, New Milford, both of 5,225,183 7/1993 Purewal et al. ........................... 424/45 Conn.; Jurgen Hubert Nagel 5.439,670 8/1995 Purewal et al. ... 424/45 Ingelheim/Rhein, Germany s 5,605,674 2/1997 Purewal et al. ........................... 424/45 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 73 Assignee: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, 0372 777 6/1990 European Pat. Off.. Conn. Primary Examiner Raj Bawa Attorney, Agent, or Firm Morgan & Finnegan, LLP 21 Appl.pp No.: 08/843,180 57 ABSTRACT 22 Filed: Apr. 14, 1997 Stabilized medicinal aeroSol Solution formulations compris O O ing medicaments that degrade or decompose by interaction Related U.S. Application Data with solvents or water, an HFC propellant, a cosolvent and an acid are described. Further, Specific medicinal aeroSol 63 Staggypt.NE "A iGs Solution formulations comprising ipratropium bromide or No. 08/153.549, Nov. 22, 1993, abandoned E. is a fenoterol, ethyl alcohol, 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane or 1,1,1, continuation-in-part of application No. 07/987,852, Dec. 9, 2,3,3,3-heptafluoropropane, and either an inorganic acid or 1992, abandoned. an organic acid are described. The acids are present in 51 Int. -

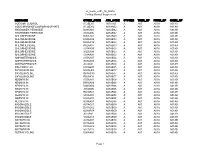

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention, Updated 2016

GlobalGlobal InitiativeInitiative forfor ChronicChronic ObstructiveObstructive LungLung DiseaseDisease REPRODUCE OR ALTER NOT MATERIAL-DO POCKET GUIDE TO COPDCOPYRIGHTED DIAGNOSIS, MANAGEMENT, AND PREVENTION A Guide for Health Care Professionals UPDATED 2016 REPRODUCE OR ALTER NOT MATERIAL-DO COPYRIGHTED Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention, Updated 2016 GOLD Board of Directors Marc Decramer, MD, Chair Peter Frith, MD University of Leuven Repatriation General Hospital, Adelaide Leuven, Belgium South Australia, Australia Alvar G. Agusti, MD David Halpin, MD Universitat de Barcelona Royal Devon and ExeterREPRODUCE Hospital Barcelona, Spain Devon, UK OR Jean Bourbeau, MD M.Victorina López Varela, MD McGill University Health Centre Universidad de la República Montreal, Quebec, Canada Montevideo, Uruguay ALTER Bartolome R. Celli, MD Masaharu Nishimura, MD Brigham and Women’s Hospital HokkaidoNOT Univ School of Medicine Boston, Massachusetts, US Sapporo, Japan Rongchang Chen, MD Claus Vogelmeier, MD Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Disease University of Gießen and Marburg Guangzhou, PRC Marburg, Germany Gerard Criner, MD Temple University School of MedicineMATERIAL-DO Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US GOLD Science Committee Nicolas Roche, MD, France Jørgen Vestbo, MD, Denmark, UK, Chair Roberto Rodriguez Roisin, MD, Spain Alvar Agusti, MD, Spain Donald Sin, MD, Canada Antonio Anzueto, MD, USA Dave Singh, MD, UK Marc Decramer, MD, Belgium Robert A. Stockley, MD, UK LeonardoCOPYRIGHTED M. Fabbri, MD, Italy Jadwiga A. Wedzicha, MD, UK Fernando Martinez, MD, USA GOLD Science Director Suzanne Hurd, PhD, USA GOLD National Leaders Representatives from many countries serve as a network for the dissemination and implementation of programs for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. -

Newer Therapies in COPD

CHAPTER Newer Therapies in COPD 50 Prem Parkash Gupta INTRODUCTION therapies are available for the patients with difficulties in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), a smoking cessation like withdrawal symptoms. In some common preventable and treatable disease, is characterized countries, influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive also recommended as a preventive therapy as a part of and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory National Guidelines. response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles PHARMACOTHERAPIES ESTABLISHED IN VARIOUS or gases. Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute significantly to the overall severity in individual patients. GUIDELINES COPD affects nearly 8% of the world’s population Primary intention of any pharmacological therapy in concerning 160 million people. COPD is a leading cause COPD is to reduce symptoms, decrease the frequency of morbidity and mortality worldwide and results in an and severity of exacerbations, and improve health related economic and social burden that is both substantial and quality of life status and exercise tolerance. COPD increasing. The prevalence of COPD is directly related to medicines available presently have not been conclusively the prevalence of tobacco smoking (being the strongest shown to modify the long-term decline in lung function risk factor ever known), although, outdoor, occupational that is the hallmark of this disease. The recommended and indoor air pollution are also major COPD risk factors. medications as per Global Initiative for Chronic The burden of COPD is likely to increase in the coming Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines (2016) are decades due to continued exposure to COPD risk factors mentioned in tabular form in Table 2. -

Screening for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: a Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S

Evidence Synthesis Number 130 Screening for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. HHSA-290-2012-00015-4, Task Order No. 4 Prepared by: Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Portland, OR Investigators: Janelle M. Guirguis-Blake, MD Caitlyn A. Senger, MPH Elizabeth M. Webber, MS Richard Mularski, MD, MSHS, MCR Evelyn P. Whitlock, MD, MPH AHRQ Publication No. 14-05205-EF-1 April 2016 This report is based on research conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. HHSA-290-2012-00015-4, Task Order No. 4). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for the application of clinical judgment. Anyone who makes decisions concerning the provision of clinical care should consider this report in the same way as any medical reference and in conjunction with all other pertinent information (i.e., in the context of available resources and circumstances presented by individual patients). -

Drugs/Medications Known to Cause Hyperhidrosis Certain Prescriptions

Drugs/Medications Known to Cause Hyperhidrosis Certain prescriptions and non-prescription medications can cause hyperhidrosis (excess perspiration or sweating) as a side effect. A list of potentially sweat-inducing medications is provided below. Medications are listed alphabetically by generic name. U.S. brand names are given in parentheses, if applicable. This list is provided as a resource and a service. It is not exhaustive and is in no way meant to replace consultation with a medical professional. Although sweating is a known side effect of the medications listed below, in most cases only a small percentage of people using the medicines experience undue sweating (in some cases less than 1%). Medications noted with an “*” and in bold are the most likely to cause sweating and the frequency of sweating as a side effect from these medications may be as high as 50%. Medications noted with an “†” are commonly-prescribed drugs; and those with a “P” are often used for pediatrics. Key: */Bold -- Known to commonly cause hyperhidrosis † -- Commonly-prescribed drugs P -- Pediatric use Abciximab (ReoPro®) Acamprosate (Campral®) Acetaminophen and Tramadol (Ultracet™) Acetophenazine (NA) Acetylcholine (Miochol-E®) P Acetylcysteine (Acetadote®) P Acitretin (Soriatane®) Acrivastine and Pseudoephedrine (Semprex®-D) † Acyclovir (Zovirax®) P Adenosine (Adenocard®; Adenoscan®) † Albuterol (Proventil® HFA Inhalation Aerosol) Alemtuzumab (Campath®) Alizapride (NA) Almotriptan (Axert™) Alosetron (Lotronex®) Amonafide (NA) Ambenonium (Mytelase®) Amitriptyline -

May 2018 Comparator Descriptions and Specifications

Respiratory Dashboard Version: May 2018 Comparator Descriptions and Specifications V1.0 01.05.2018 Page 1 of 17 NHSBSA Copyright 2018 Contents Background 3 Purpose 3 Limitations 3 Table 1: List of comparators 3 Prescribing data used in these comparators 4 How to use these comparators 4 Data quality assurance 5 Respiratory Comparator Specifications 6 High dose ICS items as a % of all ICS items 6 Inhaled steroid prevention including ICS LABA 9 Prescribing of montelukast 10 Prescribing frequency of prednisolone 5mg tablets 11 Prescribing of smoking cessation products inc. nicotine replacement (NRT), varenicline and bupropion 13 Excess SABA prescribing 14 Patients on triple therapy 15 Appendix 1 17 Working group: 17 V1.0 01.05.2018 Page 2 of 17 NHSBSA Copyright 2018 Background Respiratory prescribing is highly complex, with a huge variety of inhalers and medicines available. There are several illnesses affecting the respiratory system, but the main two areas of interest for this dashboard are asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Patients with other illnesses will be included in the results of the comparators, but the group has not considered the evidence for illnesses other than asthma and COPD. Purpose The purpose of this dashboard is to allow prescribers to see some clinically appropriate comparators that have been developed by clinicians to support better prescribing. The comparators do not show ‘good’ or ‘bad’ prescribing, but allow users to see variation and identify areas of interest for further investigation and/ or patient review. Limitations Historically, primary care prescribing information was derived from the reimbursement processes for dispensed medicines.