Chapter I the Bard Maclean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brae Lochaber Gaelic Oral Tradition and the Repertoire of John Macdonald, Highbridge

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRAE LOCHABER GAELIC ORAL TRADITION AND THE REPERTOIRE OF JOHN MACDONALD, HIGHBRIDGE Andrew Esslemont Macintosh Wiseman A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Celtic Department Faculty of Arts The University of Glasgow October 1996 © A.E.M. Wiseman 1996 ProQuest Number: 10992213 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992213 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

The Last Man"

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2016 Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man" Kathryn Joan Darling College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Darling, Kathryn Joan, "Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man"" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 908. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/908 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The apocalypse has been written about as many times as it hasn’t taken place, and imagined ever since creation mythologies logically mandated destructive counterparts. Interest in the apocalypse never seems to fade, but what does change is what form that apocalypse is thought to take, and the ever-keen question of what comes after. The most classic Western version of the apocalypse, the millennial Judgement Day based on Revelation – an absolute event encompassing all of humankind – has given way in recent decades to speculation about political dystopias following catastrophic war or ecological disaster, and how the remnants of mankind claw tooth-and-nail for survival in the aftermath. Desolate landscapes populated by cannibals or supernatural creatures produce the awe that sublime imagery, like in the paintings of John Martin, once inspired. The Byronic hero reincarnates in an extreme version as the apocalyptic wanderer trapped in and traversing a ruined world, searching for some solace in the dust. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

Nova Scotia Inland Water Boundaries Item River, Stream Or Brook

SCHEDULE II 1. (Subsection 2(1)) Nova Scotia inland water boundaries Item River, Stream or Brook Boundary or Reference Point Annapolis County 1. Annapolis River The highway bridge on Queen Street in Bridgetown. 2. Moose River The Highway 1 bridge. Antigonish County 3. Monastery Brook The Highway 104 bridge. 4. Pomquet River The CN Railway bridge. 5. Rights River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. 6. South River The Highway 104 bridge. 7. Tracadie River The Highway 104 bridge. 8. West River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. Cape Breton County 9. Catalone River The highway bridge at Catalone. 10. Fifes Brook (Aconi Brook) The highway bridge at Mill Pond. 11. Gerratt Brook (Gerards Brook) The highway bridge at Victoria Bridge. 12. Mira River The Highway 1 bridge. 13. Six Mile Brook (Lorraine The first bridge upstream from Big Lorraine Harbour. Brook) 14. Sydney River The Sysco Dam at Sydney River. Colchester County 15. Bass River The highway bridge at Bass River. 16. Chiganois River The Highway 2 bridge. 17. Debert River The confluence of the Folly and Debert Rivers. 18. Economy River The highway bridge at Economy. 19. Folly River The confluence of the Debert and Folly Rivers. 20. French River The Highway 6 bridge. 21. Great Village River The aboiteau at the dyke. 22. North River The confluence of the Salmon and North Rivers. 23. Portapique River The highway bridge at Portapique. 24. Salmon River The confluence of the North and Salmon Rivers. 25. Stewiacke River The highway bridge at Stewiacke. 26. Waughs River The Highway 6 bridge. -

The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century

THE VIKINGS IN SCOTLAND AND IRELAND IN THE NINTH CENTURY - DONNCHADH Ó CORRÁIN 1998 ABSTRACT: This study attempts to provide a new framework for ninth-century Irish and Scottish history. Viking Scotland, known as Lothlend, Laithlinn, Lochlainn and comprising the Northern and Western Isles and parts of the mainland, especia lly Caithness, Sutherland and Inverness, was settled by Norwegian Vikings in the early ninth century. By the mid-century it was ruled by an effective royal dyna sty that was not connected to Norwegian Vestfold. In the second half of the cent ury it made Dublin its headquarters, engaged in warfare with Irish kings, contro lled most Viking activity in Ireland, and imposed its overlordship and its tribu te on Pictland and Strathclyde. When expelled from Dublin in 902 it returned to Scotland and from there it conquered York and re-founded the kingdom of Dublin i n 917. KEYWORDS: Vikings, Vikings wars, Vestfold dynasty, Lothlend, Laithlind, Laithlin n, Lochlainn, Scotland, Pictland, Strathclyde, Dublin, York, Cath Maige Tuired, Cath Ruis na Ríg for Bóinn, Irish annals, Scottish Chronicle, battle of Clontarf, Ímar , Amlaíb, Magnus Barelegs. Donnchadh Ó Corráin, Department of History, University College, Cork [email protected] Chronicon 2 (1998) 3: 1-45 ISSN 1393-5259 1. In this lecture,1 I propose to reconsider the Viking attack on Scotland and I reland and I argue that the most plausible and economical interpretation of the historical record is as follows. A substantial part of Scotlandthe Northern and W estern Isles and large areas of the coastal mainland from Caithness and Sutherla nd to Argylewas conquered by the Vikings2 in the first quarter of the ninth centu ry and a Viking kingdom was set up there earlier than the middle of the century. -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

The Clan Gillean

Ga-t, $. Mac % r /.'CTJ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/clangilleanwithpOOsinc THE CLAN GILLEAN. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox, a Piccadilly, London. Colonel Sir PITZROY DONALD MACLEAN, Bart, CB. Chief of the Clan. v- THE CLAN GILLEAN BY THE REV. A. MACLEAN SINCLAIR (Ehartottftcton HASZARD AND MOORE 1899 PREFACE. I have to thank Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald Maclean, Baronet, C. B., Chief of the Clan Gillean, for copies of a large number of useful documents ; Mr. H. A. C. Maclean, London, for copies of valuable papers in the Coll Charter Chest ; and Mr. C. R. Morison, Aintuim, Mr. C. A. McVean, Kilfinichen, Mr. John Johnson, Coll, Mr. James Maclean, Greenock, and others, for collecting- and sending me genea- logical facts. I have also to thank a number of ladies and gentlemen for information about the families to which they themselves belong. I am under special obligations to Professor Magnus Maclean, Glasgow, and Mr. Peter Mac- lean, Secretary of the Maclean Association, for sending me such extracts as I needed from works to which I had no access in this country. It is only fair to state that of all the help I received the most valuable was from them. I am greatly indebted to Mr. John Maclean, Convener of the Finance Committee of the Maclean Association, for labouring faithfully to obtain information for me, and especially for his efforts to get the subscriptions needed to have the book pub- lished. I feel very much obliged to Mr. -

King of the Danes’ Stephen M

Hamlet with the Princes of Denmark: An exploration of the case of Hálfdan ‘king of the Danes’ Stephen M. Lewis University of Caen Normandy, CRAHAM [email protected] As their military fortunes waxed and waned, the Scandinavian armies would move back and forth across the Channel with some regularity [...] appearing under different names and in different constellations in different places – Neil Price1 Little is known about the power of the Danish kings in the second half of the ninth century when several Viking forces ravaged Frankia and Britain – Niels Lund2 The Anglo-Saxon scholar Patrick Wormald once pointed out: ‘It is strange that, while students of other Germanic peoples have been obsessed with the identity and office of their leaders, Viking scholars have said very little of such things – a literal case of Hamlet without princes of Denmark!’3 The reason for this state of affairs is two-fold. First, there is a dearth of reliable historical, linguistic and archaeological evidence regarding the origins of the so-called ‘great army’ in England, except that it does seem, and is generally believed, that they were predominantly Danes - which of course does not at all mean that they all they came directly from Denmark itself, nor that ‘Danes’ only came from the confines of modern Denmark. Clare Downham is surely right in saying that ‘the political history of vikings has proved controversial due to a lack of consensus as to what constitutes reliable evidence’.4 Second, the long and fascinating, but perhaps ultimately unhealthy, obsession with the legendary Ragnarr loðbrók and his litany of supposed sons has distracted attention from what we might learn from a close and separate examination of some of the named leaders of the ‘great army’ in England, without any inferences being drawn from later Northern sagas about their dubious familial relationships to one another.5 This article explores the case of one such ‘Prince of Denmark’ called Hálfdan ‘king of the Danes’. -

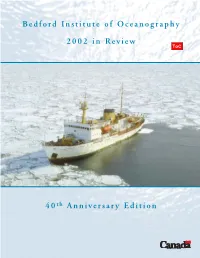

2002 in Review

Bedford Institute of Oceanography 2002 in Review 40th Anniversary Edition BIO-2002 IN REVIEW 1 Change of address notices, requests for copies, and other correspondence regarding this publication should be sent to: The Editor, BIO 2002 in Review Bedford Institute of Oceanography P.O. Box 1006 Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Canada, B2Y 4A2 E-mail address:[email protected] The cover image is the CSS Hudson in the Canadian Arctic in the late 1980s. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2003 Cat. No. Fs75-104/2002E ISBN: 0-662-34402-2 ISSN: 1499-9951 Aussi disponible en français. Editor: Dianne Geddes, BIO. Editorial team: Shelley Armsworthy, Pat Dennis, and Bob St-Laurent. Photographs: BIO Technographics, the authors, and individuals/agencies credited. Design: Channel Communications, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Natural Resources Canada Bedford Institute of Oceanography 1 Challenger Drive P. O. Box 1006 Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada B2Y 4A2 BIO web site address: www.bio.gc.ca INTRODUCTION Anniversaries, in this case our 40th, are an opportunity for both celebration and reflection. We very much enjoyed our year of celebrations. Open House 2002, the special lecture by David Suzuki, the Symposium on the Future of Marine Science, and the Symphony Nova Scotia concert all contributed to the sense of community that is a strong characteristic of the Institute. The lectures by Dale Buckley (during the opening ceremonies for open house) and by Bosko Loncaravic (the first lecture of our symposium) provided rich memories of research high- lights over four decades. Both talks emphasized the key role of scientific advice to the government of Canada (such as input to the Gulf of Maine boundary dispute decided upon at the World Court in The Hague and the Arrow oil spill in Chedabucto Bay).