What Is History Now?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2018 Celebrating Our 45Th

Celebrating our 45th Anniversary, p. 2 Stowe Restoration Project, pgs. 3-4 The Trevelyans of Wallington Hall, pgs. 5-6 Spring 2018 1 | From the Executive Director Dear Members & Friends, THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 2018 marks Royal Oak’s 45th Anniversary. We Churchill’s studio at Chartwell give tangible 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org will celebrate this in many ways—more with a expression to the many new interpretive focus on where we are as an organization today programs that will excite visitors daily just as and what we hope for in the future. the exhibition did 35 years ago. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Honorary Chairman In reviewing some of the histories of Royal Other big news for 2018 is our appeal to help Mrs. Henry J. Heinz II Oak, I was surprised to find an event in 1983 the National Trust finish off a multi-year and Chairman that was noted as pivotal in transforming multi-task restoration effort for Stowe. Stowe Lynne L. Rickabaugh the Foundation’s relationship is one of the leading garden and Vice Chairman with the Trust from one of just landscape properties in England Prof. Susan S. Samuelson growing ‘friendship’ to one of a and has a wide significance in Treasurer serious fundraising partnership. the history of garden design in Renee Nichols Tucei The connections of this historic Europe, Russia and America (see Secretary event with what Royal Oak has pages 3-4). It is among the most Thomas M. Kelly more recently accomplished and visited Trust properties. -

Disraeli and the Early Victorian ‘History Wars’ – Daniel Laurie-Fletcher

Disraeli and the Early Victorian ‘History Wars’ – Daniel Laurie-Fletcher FJHP Volume 25 (2008 ) Disraeli and the Early Victorian ‘History Wars’ Daniel Laurie-Fletcher Flinders University The American historian, Gertrude Himmelfarb, once put the question: ‘Who now reads Macaulay?’ Her own reply to the rhetorical question was: Who, that is, except those who have a professional interest in him–and professional in a special sense: not historians who might be expected to take pride in one of their most illustrious ancestors, but only those who happen to be writing treatises about him. In fact, most professional historians have long since given up reading Macaulay, as they have given up writing the kind of history he wrote and thinking about it as he did. i The kind of history and thinking Himmelfarb was referring to is the ‘Whig interpretation of history’ which is one based on a grand narrative that demonstrated a path of inevitable political and economic progress, a view made famous by the Whig politician and historian Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859). ii In his History of England: From the Accession of James II (1848-1860), Macaulay maintained that the development of political institutions of the nation had brought increased liberties accompanied by the growth of economic prosperity. Macaulay’s study was begun when the educated classes of early Victorian Britain held a widespread fear of a French-style revolution during a time of extensive social, economic and political change. Many, in order to cope with such changes, looked to British history to yield role models as well as cautionary tales of what to avoid in creating a better society. -

Some Pages from the Book

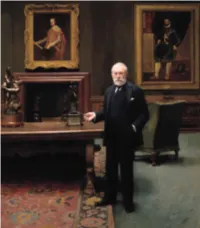

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009

PHILANTHROPY / EVENT TRANSCRIPT The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009 By Irving Kristol Edited by Gertrude Himmelfarb February 2, 2011 Panel Discussion of The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009 By Irving Kristol Edited by Gertrude Himmelfarb Wednesday, February 2, 2011 Table of Contents Ken Weinstein 1 Amy Kass 1 Charles Krauthammer 3 Irwin Stelzer 7 Leon Kass 11 William Kristol 15 Q&A 23 Gertrude Himmelfarb (“Bea Kristol”) 30 Speaker Biographies 31 © 2011 Hudson Institute Hudson Institute is a nonpartisan, independent policy research organization. Founded in 1961, Hudson is celebrating a half century of forging ideas that promote security, prosperity, and freedom. www.hudson.org Ken Weinstein Good afternoon. I’m Ken Weinstein, CEO of Hudson Institute. I’d like to welcome everyone to today’s Book Forum on the newly published The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays 1942- 2009, by Irving Kristol, which has been edited by the redoubtable Gertrude Himmelfarb. The book is available for sale in the back at the discounted price of $20, and I urge all of you to get one before you leave. This is a truly remarkable book, one that shows the breadth and the depth of Irving Kristol’s thought over some 67 years, which you’ll be hearing about shortly. My colleagues and I frankly feel privileged that Hudson Institute is the venue for today’s book forum, and I should thank the book’s editor, Gertrude Himmelfarb, for giving us this auspicious honor. (Applause.) We have a truly distinguished panel, who will offer their reflections shortly, but before we get underway I should note that this is Hudson Institute’s 50th anniversary year, and to mark this occasion, the Institute has begun a 50th anniversary seminar series, and today’s exceptional Book Forum is the second event in this series. -

Postmodern Theory of History: a Critique

Postmodern Theory of History: A Critique Trygve R. Tholfsen Teachers College, Columbia University 1. Among the more striking spinoffs of postmodernism in the past fifteen years or so has been an arresting theory of history. On the assumption that "the historical text is an object in itself, made entirely from language, and thus subject to the interrogations devised by the sciences of language use from ancient rhetoric to modern semiotics"1, postmodernists have set out to enlighten historians about their discipline. From that perspective, they have emphasized the intrinsic fictionality of historical writing, derided the factualist empiricism that purportedly governs the work of professional historians, dismissed the ideal of objectivity as a myth, and rejected the truth claims of traditional historiography. Historians have been invited to accept the postmodern approach as a means to critical self reflection and to the improvement of practice. Some postmodern theorists have taken a more overtly anti-histori• cal line that bears directly on important questions of theory and prac• tice. Rejecting the putative "autonomy" claims of professional histo• riography, they dismiss the notion of a distinctively "historical" mode of understanding the past. On this view, the study of origins and de• velopment is of limited analytical value; and the historicist principle of historical specificity or individuality is the remnant of a venerable tradition that has been displaced. It follows that historians ought to give up their claim to special authority in the study of the past. This article will concentrate on the postmodern rejection of the notion that the past has to be understood "historically." 1 Hans KELLNER, "Introduction: Describing Re-Descriptions" in Frank ANKERSMIT and Hans KELLNER (eds.), A New Philosophy of History, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. -

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Postmaster and the Merton Record 2019

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2019 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Edited by Timothy Foot (2011), Claire Spence-Parsons, Dr Duncan From the Acting Warden......................................................................4 Barker and Philippa Logan. JCR News .................................................................................................6 Front cover image MCR News ...............................................................................................8 St Alban’s Quad from the JCR, during the Merton Merton Sport ........................................................................................10 Society Garden Party 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Hockey, Rugby, Tennis, Men’s Rowing, Women’s Rowing, Athletics, Cricket, Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Awards Additional images (unless credited) 4: Ian Wallman Clubs & Societies ................................................................................22 8, 33: Valerian Chen (2016) Halsbury Society, History Society, Roger Bacon Society, 10, 13, 36, 37, 40, 86, 95, 116: John Cairns (www. Neave Society, Christian Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, johncairns.co.uk) Tinbergen Society 12: Callum Schafer (Mansfield, 2017) 14, 15: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Interdisciplinary Groups ....................................................................32 16, 22, 23, 24, 80: Joseph Rhee (2018) Ockham Lectures, History of the Book Group 28, 32, 99, 103, 104, 108, 109: Timothy Foot -

Historical Argument and Practice Bibliography for Lectures 2019-20

HISTORICAL ARGUMENT AND PRACTICE BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR LECTURES 2019-20 Useful Websites http://www.besthistorysites.net http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/index.html http://www.jstor.org [e-journal articles] http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/ejournals_list/ [all e-journals can be accessed from here] http://www.historyandpolicy.org General Reading Ernst Breisach, Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983) R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946) Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998) Donald R. Kelley, Fortunes of History: Historical Inquiry from Herder to Huizinga (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003) R. J. Evans, In Defence of History (2nd edn., London, 2001). E. H. Carr, What is History? (40th anniversary edn., London, 2001). Forum on Transnational History, American Historical Review, December 2006, pp1443-164. G.R. Elton, The Practice of History (2nd edn., Oxford, 2002). K. Jenkins, Rethinking History (London, 1991). C. Geertz, Local Knowledge (New York, 1983) M. Collis and S. Lukes, eds., Rationality and Relativism (London, 1982) D. Papineau, For Science in the Social Sciences (London, 1978) U. Rublack ed., A Concise Companion to History (Oxford, 2011) Q.R.D. Skinner, Visions of Politics Vol. 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge, 2002) David Cannadine, What is History Now, ed. (Basingstoke, 2000). -----------------------INTRODUCTION TO HISTORIOGRAPHY---------------------- Thu. 10 Oct. Who does history? Prof John Arnold J. H. Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction (2000), particularly chapters 2 and 3 S. Berger, H. Feldner & K. Passmore, eds, Writing History: Theory & Practice (2003) P. -

History 80020 – Literature Survey – European History Tuesdays, 6:30-8

History 80020 – Literature Survey – European History Tuesdays, 6:30-8:30pm (classroom TBA) Professor Steven Remy ([email protected]) Weekly office hour: Tuesdays 5-6 (room TBA) This course has two purposes: (1) to introduce you to recent scholarship on the major events, themes, and historiographical debates in European history from the Enlightenment to the present; and (2) to prepare you to take the written exam in this field. Each week you will read - and come to class prepared to summarize and discuss - a different title. The titles are assigned below. Each student will write a 700-900 word summary of the book s/he has been assigned and bring a paper copy for me and for each of his/her classmates. I will determine your final course grade as follows: 60% book summaries and 40% in class discussions. Written book summary and class participation requirements are found at the end of the syllabus. A word about the titles I’ve selected: I have selected high-quality scholarship reflecting the temper and direction of current research on and methodological approaches to modern European history. I have also emphasized literature that situates European developments in global contexts. An expanded list of titles for further reading is attached to the syllabus. In addition to keeping up with scholarly journals in your area of interest, I encourage you to stay current by tracking reviews and debates in the following publications: Journal of Modern History, The New York Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books, aldaily.com, H-Net reviews, The Nation, Jewish Review of Books, and Chronicle of Higher Education book reviews. -

We All Global Historians Now? an Interview with David Armitage

Itinerario http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI Additional services for Itinerario: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage Martine van Ittersum and Jaap Jacobs Itinerario / Volume 36 / Issue 02 / August 2012, pp 7 28 DOI: 10.1017/S0165115312000551, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0165115312000551 How to cite this article: Martine van Ittersum and Jaap Jacobs (2012). Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage. Itinerario, 36, pp 728 doi:10.1017/S0165115312000551 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI, IP address: 128.103.149.52 on 02 Nov 2012 7 Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage BY MARTINE VAN ITTERSUM AND JAAP JACOBS The interview took place on a splendid summer day in Cambridge, Massa- chusetts. The location was slightly exotic: the interviewers had lunch with David Armitage at Upstairs at the Square, an eatery which sports pink and mint green walls, zebra decorations, and even a stuffed crocodile. What more could one want? Armitage was recently elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. At the time of the interview, he was just about to take over as Chair of the History Department at Harvard University. His long-awaited Foundations of Modern International Thought (2013) was being copy-edited for publication.1 Granted a sneak preview, the interviewers can recommend it to every Itinerario reader. In short, it was high time for Itinerario to sit down with one of the movers and shakers of the burgeoning field of global and international history for a long and wide-ranging conversation. -

Chief Justice John Roberts Is a Robot

CHIEF JUSTICE JOHN ROBERTS IS A ROBOT Ian Kerr* and Carissima Mathen** I Introduction The title of this article is not pejorative. It is suggestive. It asks readers to imagine the following counterfactual. Around the globe, people awaken to some very strange news. In different languages, the same headline thunders: "Chief Justice John Roberts is a Robot". Rendered unconscious during an ambush and attempted kidnapping while attending a conference at the House of Lords, Chief Justice Roberts’ captors boldly deliver-him- up to the Royal London Hospital and speed off. In urgent and unusual circumstances—and in breach of US and international protocols—a team of emergency surgeons cut him open to save his life. That is when they discovered that his biology only runs skin deep. The Chief Justice, it turns out, was a robot. Despite heroic efforts, the surgical staff was unable to revive the Chief. Several renowned teams of surgeons, computer scientists and experts in the fields of cybernetics and artificial intelligence were subsequently consulted with numerous further unsuccessful attempts to reanimate him. Devout practitioners of Kabbalah were called in. They offered various incantations but, upon failure to resurrect JR-R, concluded that the robot, like the great Golem of Prague, had outlived its divine purpose. After weeks of follow-up investigations and interviews, it is learned that "John Roberts" did indeed graduate from Harvard Law School in 1979 and that "his" legal career unfolded exactly as documented in public life. However, John Roberts, Robot (JR-R) was in fact a highly advanced prototype of the US Robots and Mechanical Men Corporation, developed during the period chronologically corresponding with what * Canada Research Chair in Ethics, Law & Technology, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Philosophy, School of Information Studies, University of Ottawa ([email protected]).