Riverside East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Request for Joint Petition to Amend to Delete TRANS-8

DOCKETED Docket Number: 09-AFC-06C Project Title: Blythe Solar Power Project - Compliance TN #: 232709 Document Title: Request For Joint Petition To Amend to Delete TRANS-8 Description: N/A Filer: Scott Galati Organization: DayZenLLC Submitter Role: Applicant Representative Submission Date: 4/10/2020 10:58:28 AM Docketed Date: 4/10/2020 BLYTHE SOLAR POWER PROJECT REQUEST FOR JOINT PETITION To AMEND DELETION OF TRANS-8 Submitted by: NextEra Blythe Solar Energy Center, LLC Submitted to: California Energy Commission April 2020 Prepared by: Section 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND NextEra Blythe Solar Energy Center, LLC (Blythe Solar), a wholly owned subsidiary of NextEra Energy Resources LLC, is the current owner of the Blythe Solar Power Project (BSPP). Blythe Solar files this Request For a Joint Petition To Amend1 (Petition) to delete Condition of Certification TRANS-8 which requires that Blythe Solar provide an avigation easement executed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). BLM will not encumber its land with such an avigation easement, therefore making it a legal impossibility for Blythe Solar to comply with TRANS-8. As discussed in this Petition, TRANS-8 was included in the original and amended Final Decisions in order to ensure compliance with a provision requiring an avigation easement in the Riverside County Airport Land Use Commission Airport Master Plan (Airport Master Plan). The requirement was determined to be a Law, Ordinance, Regulation, or Standard (LORS) and was not included to mitigate any potential environmental impact. Further research definitely proves that the requirements of the Airport Master Plan are inapplicable to BLM land and therefore should not have been applied to the BSPP as a LORS. -

A Memorial Volume Dedicated to Those Men and Women of Delaware

� '\§] y � � £R)� � � � � � £R) IN MEMORIAM � * 2; (iVi) � � d � � � � vw � * * F liiiil � A Memorial Volume � y � � @S Dedicated to those Men and Women vw � of Delaware � * who lost their lives � 25 � � During World War II � © � © � � � * � * � � @ � � � � � � 25 Compiled by the � � Public Archives Commission � State of Delaware � � � Dover, Delaware y 1944-1949 * � @5 £R) � � � � � � � f? �O�OlLW f?<C���Olro©f? (ro@ffa��[ro©W 1;:( �[ro�O@ f? STATE OF DELA.."W".ARE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT W".ALTER "'· BACON DOVER OOVER...�OR July 20, 1948 On March 14, 1944, I wrote to the Public Archives Commission expressing appreciation to them and to the volunteers who assisted them in the collection of data illustrative of Delaware's participation in World War II. At the same time I made the following request: "It occurs to me that your Commission could render further service to the State and its citizens by compiling information of all Delawareans who have, or may lose their lives while serving in the Armed Forces of the United States. It seems to me it would be appropriate to record the names of these honored dead in a memorial volume to be preserved in the State Archives as a heritage for future generations. If this suggested plan is acceptable to your Commission, I hope that this work may begin in the near future.n It is indeed gratifying to learn from a recent Report of the State Archivist that this work has progressed through the war years and is now nearing a completion. Efforts have not been spared to locate the next of kin of these deceased members of the Armed Forces from our State and to verify the facts contained in the biographical sketches on the following pages. -

W Military Service Report

West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: WAAG LAMONTE E. Address: 87 FLOHR AVENUE Service Branch:ARMY Rank: PVT Unit / Squadron: COMPANY "C", 728TH RAILWAY OPERATIONS BATTALION Medals / Citations: EUROPEAN-AFRICAN-MIDDLE EASTERN CAMPAIGN MEDAL Theater of Operations / Assignment: EUROPEAN THEATER Service Notes: Private Base Assignments: Miscelleaneous: The 728th Railway Operating Battalion consisted of many employees from the L&N (Louisville & Nashville) Railroad, and was instrumental in supporting the Allied advance through France in the months following D-Day / The L&N helped re-open and operate the railroad from Cherbourg, France to Paris The European-African-Middle Eastern (EAME) Campaign Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on 6 November 1942 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt / The medal was intended to recognize those military service members who had performed military duty in the European Theater (to include North Africa and the Middle East) and was awarded for any service performed between 7 December 1941 and 2 March 1946 / The European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal was awarded as a service ribbon throughout the entire Second World War 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: WADE LIONEL Address: Service Branch:NAVY Rank: SO.M. 3/C Unit / Squadron: USS PLOVER (YMS-442) Medals / Citations: EUROPEAN-AFRICAN-MIDDLE EASTERN CAMPAIGN MEDAL Theater -

File Date Location Aircraft Accident/Incio Nt Report

NATIJN~L TRANSPD~·ATI ~ETY BOARD WA5HlNGrON, D.C U594 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT/INCIO NT REPORT ORIU FGRMAT U.S. CIVIL AVIATION FILE DATE LOCATION AIRCRAFT DATA INJURIES FLIGHT PI LOT DATA F S M/N PURPOSE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~--------~---~-------~ 3-1834 6/7/77 RIVERSIDE,CA CESSNA 177RG CR 0 0 NONCOMMERCIAL PRIVAtE, AGE 49T 781 TIME - 2340 N1599H PX- 0 0 PLEASURE/PERSONAL TRANSP TOTAL HOURS, ·472 IN TYPE, DAMAGE-DESTROYED NOT INST~UMENT RATED. NAME OF AIRPORT - RIVERSIDE DEPARTURE POINT INTENDED DESTINATION RIVERSIDE,CA BLYTHE,CA ~YPE OF ACCIDENT PHASE OF OPERATtON COLLISION WITH GROUND/WATER: UNCONTROLLED IN FLIGHT: UNCON~ROLLED DESCENT PROBABLE CAUSE(S) PILOT IN COMMAND - SPATIAL DISORIENTATION FACTOR ( S) WEATHER - OBSTRUCTIONS TO VISION WEATHER BRIEFING - UNKNOWN/NOT REPORTED SKY CONDITION CE! LING AT ACCIDE:."T SITE PARTIAL OBSCURATION UNKNOWN/NOT REPORTED VISIBILITY AT ACCIDENT SITE PRECIPITATION AT ACCIDENT SITE 4 MILES OR LESS NONE OBSTRUCTIONS TO VISION AT ACCIDENT SITE WIND DIRECTION-DEGREES HAZE 260 WIND VELOCITY-KNOTS TYPE OF WEATHER CONDITIONS 5 VFR TYPE OF FLIGHT PLAN NONE PAGE 55 ,, ·~------------------------ .-------l~ATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD PAGE_l_OF~_l_PAGES ACCIDENT FILE CONTENTS ,,,4,// TRANSPORTATION MODE [ }{] AVIATION [ ] HIGHWAY [ ] PIPELINE NTSB FILE NO. [ ] INTERMODAL [ ] MARINE [ ] RAILROAD LAX 77-F-A050 IDENTIFICATION OF ACCIDENT Riverside, California 06-07-77 Cessna 177RG, N-1599H NO. OF PAGES ITEM DESCRIPTION OF ITEM NO. ooc. B&W COLOR PHOTO PHOTO 1. Factual Aircraft Accident Report - General Aviation, 9 NTSB Form 6120. 4 P-~pcv J <;/_t,,/-5 2. Witness Statements A. Kennith ~. Hart 1 B. Robert M. Skilling 1 C. James Clayton 1 D. Scott Bovee 2 E. -

Supreme Sacrifice, Extraordinary Service: Profiles of SDSU Military Alumni

1 Supreme Sacrifice, Extraordinary Service: Profiles of SDSU Military Alumni by Robert Fikes, Jr., Emeritus Librarian San Diego State University January 2021 2 Contents Preface…...…………………………………………….3 SDSU War Memorial Profiles……………………….5 World War II…………………………………..……6 Korean War……………………………………….74 Vietnam War………………………………………84 Iraq & Afghanistan..………………………….……110 Non-Combat Casualties…………….…….………115 Generals & Admirals………………………………124 Outstanding Aztecs………………………………. 153 SDSU Military Benchmarks……………….……...201 Top Military Honors………………………………..205 War Memorial Statistics…………………………..216 References…………………………………………..217 SDSU War Memorial Committee Photo………..219 3 Preface This tribute to San Diego State University’s military alumni started out as one of three sabbatical projects in the fall of 2005 and was intended to be a survey of the school’s contributions to the nation’s armed forces. The inspiration for attempting this occurred several years earlier when a colleague informed me of letters written by former students serving in the military during World War II to Dr. Lauren Post (right), a popular geography professor and football coach. Post’s brainchild was a newsletter, the only one of its kind in the nation, that was distributed worldwide and kept this group of alumni in contact with one another and with those left behind on the homefront. It is the often poignant, deliberately understated experiences told in the letters by young men and women, many of whom soon perished, that demands a retelling to this and future generations. Early in the project, I began to investigate the lives of a few of the fallen heroes listed on the university’s war monument in order to have some examples to cite in an essay, but as I looked closely at the abbreviated life of one deceased person after another the more I was fascinated with each of them as individuals. -

The Salton Sea Region, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 497 THE SALTON SEA REGION, CALIFORNIA A GEOGEAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDEOLOGIC EECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PLACES BY JOHN S. BROWN Prepared in cooperation with the DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES Or THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PBOCUBED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OV DOCUMENTS GOVEBNMENT PEINTINO OFFICE WASHINQTON, D. C. AT 60 CENTS PER COPY PUECHASEE AQEEES NOT TO EESELL OB DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOB PBOFTT. PUB. EES. 57, APPBOVED MAT 11, 1922 n CONTENTS. Fact. Preface, by 0. E. Meinzer................................................ xi Introduction......................... .................................... 1 Methods and scope of work............................................. 1 Acknowledgments.......................................... .......... 2 Oeneral features of the region............................................. 2 Location............................................................. 2 Name................................................................ 2 History.............................................................. 3 Early Spanish exploration and development........................ 3 Later explorations................................................ 4 Gold seekers..................................................... 5 Pacifier Railroad explorations..................................... 5 Colorado River -

Routes to Desert Watering Places in the Salton Sea Region, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JOHN BARTON PAYNE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 490 A ROUTES TO DESERT WATERING PLACES IN THE SALTON SEA REGION, CALIFORNIA BY JOHN S. BROWN WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 1920 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JOHN BARTON PAYNE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 490 A ROUTES TO DESERT WATERING PLACES IN THE SALTON SEA REGION, CALIFORNIA BY JOHN S. BROWN Prepared in cooperation with the DEPARTMENT OP ENGINEERING OP THE STATE OP CALIFORNIA WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1920 CONTENTS. Page. Preface, by O. E. Meinzer________________^___________ 1 Introduction_______________________________________ 5 Location of the region______________________________ 5 Scope of the report_______________________________ 5 Methods of field work__________________,_________ 5 Explanation of maps_____________________________ 6 Acknowledgments_______________________________ 7 Description of the region______________________________ 7 Physical features ______________________ 7 Settlements ________________________ 7 Roads___ -______________________- 8 Means of travel ________________________ 8 Suggestions to travelers _ _____________________ 8 General advice ___________ __ - 8 Teams, hay, and grain _______ __ 9 Special suggestions to motorists________________________ 10 Provisions__ _ _______________________ 11 Clothing and bedding______________________________ 12 Fuel______________-.__________________________ 12 Water______________________________________ -

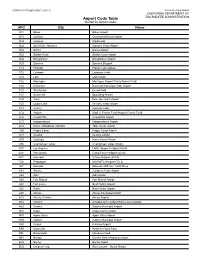

CDTFA-810-FTH Airport Code Table

CDTFA-810-FTH (S1F) REV. 1 (10-17) STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF Airport Code Table TAX AND FEE ADMINISTRATION (Sorted by Airport Code) APC City Name 0O2 Baker Baker Airport 0O4 Corning Corning Municipal Airport 0O9 Gasquet Ward Field 0Q3 Schellville / Sonoma Sonoma Valley Airport 0Q4 Selma Selma Airport 0Q5 Shelter Cove Shelter Cove Airport 0Q6 Shingletown Shingletown Airport 0Q9 Sonoma Sonoma Skypark 1C9 Hollister Frazier Lake Airpark 1O2 Lakeport Lampson Field 1O3 Lodi Lodi Airport 1O5 Montague Montague Airport (Yreka Rohrer Field) 1O6 Dunsmuir Dunsmuir Municipal-Mott Airport 1Q1 Strathmore Eckert Field 1Q2 Susanville Spaulding Airport 1Q4 Tracy New Jerusalem Airport 1Q5 Upper Lake Gravelly Valley Airport 2O1 Quincy Gansner Field 2O3 Angwin Virgil O. Parrett Field (Angwin-Parrett Field) 2O6 Chowchilla Chowchilla Airport 2O7 Independence Independence Airport 2Q3 Davis / Woodland / Winters Yolo County Airport 36S Happy Camp Happy Camp Airport 3O1 Gustine Gustine Airport 3O8 Coalinga Harris Ranch Airport 49X Chemehuevi Valley Chemehuevi Valley Airport 4C0* Los Angeles LAPD Hooper Heliport (4CA0) 4C3* Pleasanton Camp Parks Heliport (4CA3) 60C* Concord Q Area Heliport (60CA) 7C4* Bridgeport MCMWTC Heliport (7CL4) 9L2 Edwards Edwards AFB Aux. North Base A24 Alturas California Pines Airport A26 Adin Adin Airport A28 Fort Bidwell Fort Bidwell Airport A30 Fort Jones Scott Valley Airport A32 Dorris Butte Valley Airport AAT Alturas Alturas Municipal Airport ACV Arcata / Eureka Arcata Airport AHC Herlong Amedee Army Airfield (Sierra Army Depot) AJO Corona Corona Municipal Airport APC Napa Napa County Airport APV Apple Valley Apple Valley Airport AUN Auburn Auburn Municipal Airport AVX Avalon Catalina Airport BAB Marysville Beale Air Force Base BFL Bakersfield Meadows Field BIH Bishop Eastern Sierra Regional Airport BLH Blythe Blythe Airport BLU Emigrant Gap Blue Canyon - Nyack Airport CDTFA-810-FTH (S1B) REV. -

Countywide Water and Wastewater Municipal Service Review

Countywide Water and Wastewater Municipal Service Review Riverside Local Agency Formation Commission LAFCO 2019-01-1,2,3,4,5 Volume 3 Coachella Valley/Eastern Region Water and Wastewater Agencies City of Blythe, City of Coachella, City of Indio, City of Palm Springs, Chiriaco Summit County Water District, Coachella Valley Water District, Desert Water Agency, Imperial Irrigation District, Mission Springs Water District, Palo Verde Irrigation, Valley Sanitary District, County Service Area 51 (Desert Center/Lake Tamarisk), County Service Area 62 (Ripley), and County Service Area 122 (Mesa Verde) i Prepared For: Riverside Local Agency Formation Commission ___________________________________________________________ COMMISSIONERS Phil Williams, Special District Member Stephen Tomanelli, Vice Chair, Public Member Kevin Jeffries, County Member Jeff Hewitt, County Member Michael M. Vargas, City Member Steve Sanchez, Chair, City Member Nancy Wright, Special District Member ALTERNATE MEMBERS Randon Lane, City Member V. Manuel Perez, County Member Jim Love, Public Member STAFF Crystal Craig, Interim Executive Officer ii Countywide Water and Wastewater Municipal Service Review Volume 3 Riverside Local Agency Formation Commission Coachella Valley/Eastern Region Water and Wastewater Agencies Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ vi 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. -

Compliance Archaeology Has Tended to Focus on Specific Locations of Sites, While the Broader Landscape of Traditional Use Areas

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRAILS AND ETHNOGRAPHIC TRAILS: CAN THEY MEET? RUTH ARLENE MUSSER-LOPEZ ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE ASSOCIATES (RIVER AHA) STEVE MILLER BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, LAKE HAVASU FIELD OFFICE Compliance archaeology has tended to focus on specific locations of sites, while the broader landscape of traditional use areas, travel corridors, and places named in tradition is often overlooked. An opportunity for landscape-level analysis presented itself in a proposed large Off Highway Vehicle (OHV) open area adjacent to the Colorado River. While a continuous Salt Song Trail may not be physically manifest, researchers found evidence of a corridor including trail segments, stacked rock features (“prayer shrines”), and short-term camps. When taken into consideration with prehistoric events and places named in ethnographies and current traditional practices, these fragmented segments may be components of the Salt Song Trail. The Salt Song Trail and other ethnographic trails in the Mojave Desert are elements of very large- scale ethnographic landscapes. These landscapes include the land, its springs, passes, and notable peaks; the fossil traces of human behavior ranging from stone tool manufacture, sheltering, and ceremony; and the empirically observable tread or alignment of the trail itself (Figure 1). The difficulty lies in linking, or attempting to link, archaeological observations characterized by very specific locations to named ethnographic trails, which in most cases have only generalized provenience and which, in some cases, may not have an actual physical referent. The purpose of this paper is to share tentative findings of recent fieldwork in Standard Basin, Arizona, a large drainage situated on the eastern side of the Colorado River south of Lake Havasu City. -

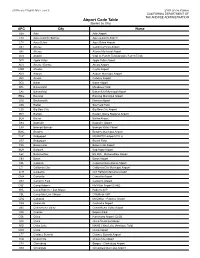

Airport Code Table

CDTFA-810-FTI (S1F) REV. 1 (10-17) STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TAX AND FEE ADMINISTRATION Airport Code Table (Sorted by City) APC City Name A26 Adin Adin Airport L54 Agua Caliente Springs Agua Caliente Airport L70 Agua Dulce Agua Dulce Airpark A24 Alturas California Pines Airport AAT Alturas Alturas Municipal Airport 2O3 Angwin Virgil O. Parrett Field (Angwin-Parrett Field) APV Apple Valley Apple Valley Airport ACV Arcata / Eureka Arcata Airport MER Atwater Castle Airport AUN Auburn Auburn Municipal Airport AVX Avalon Catalina Airport 0O2 Baker Baker Airport BFL Bakersfield Meadows Field L45 Bakersfield Bakersfield Municipal Airport BNG Banning Banning Municipal Airport O02 Beckwourth Nervino Airport O55 Bieber Southard Field L35 Big Bear City Big Bear City Airport BIH Bishop Eastern Sierra Regional Airport BLH Blythe Blythe Airport D83 Boonville Boonville Airport L08 Borrego Springs Borrego Valley Airport BWC Brawley Brawley Municipal Airport 7C4* Bridgeport MCMWTC Heliport (7CL4) O57 Bridgeport Bryant Field F25 Brownsville Brownsville Airport BUR Burbank Bob Hope Airport L62 Buttonwillow Elk Hills - Buttonwillow Airport C83 Byron Byron Airport CXL Calexico Calexico International Airport L71 California City California City Municipal Airport CLR Calipatria Cliff Hatfield Memorial Airport CMA Camarillo Camarillo Airport O61 Cameron Park Cameron Airpark C62* Camp Roberts McMillan Airport (CA62) SYL Camp Roberts / San Miguel Roberts AHP CSL Camp San Luis Obispo O’Sullivan AHP CRQ Carlsbad McClellan - Palomar Airport O59 Cedarville Cedarville Airport 49X Chemehuevi Valley Chemehuevi Valley Airport O05 Chester Rogers Field C56* Chico Ranchaero Airport (CL56) CIC Chico Chico Municipal Airport NID China Lake NAWS China Lake (Armitage Field) CNO Chino Chino Airport L77 Chiriaco Summit Chiriaco Summit Airport 2O6 Chowchilla Chowchilla Airport C14 Clarksburg Borges - Clarksburg Airport O60 Cloverdale Cloverdale Municipal Airport CDTFA-810-FTI (S1B) REV. -

Aviation & Airport Ground Access

TRANSPORTATIONAVIATION & AIRPORT GROUND SYSTEMACCESS SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION OF GOVERNMENTS APPENDIX ADOPTED I APRIL 2016 SCAG REGION AIRPORTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 SOCIO-ECONOMIC OVERVIEW 4 REGIONAL AIR PASSENGER DEMAND FORECAST 8 AIRPORT DEMAND FORECASTS 18 AIRPORT GROUND ACCESS 22 NOTES 37 APPENDIX TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM I AVIATION & AIRPORT GROUND ACCESS ADOPTED I APRIL 2016 AVIATION AND AIRPORT GROUND ACCESS SCAG REGION AIRPORTS Throughout the historic period reviewed, the domestic market accounted for the majority of origin and destination (O&D) traffic at the SCAG region airports. Although the international segment gained importance, domestic O&D traffic in 2013 still accounted for 73.4 percent INTRODUCTION of total O&D traffic, compared to 80.4 percent in 1990. In addition to O&D traffic, the airport system in the SCAG region also handles a substantial amount of connecting traffic. The As illustrated in EXHIBIT 1, the six counties of Southern California that make up the SCAG share of connecting passengers at the airports in the SCAG region has hovered around 17 region are home to an airport sywstem of more than 50 airports. The airport identifier codes percent of total enplaned and deplaned (E/D) passengers during the historic period reviewed. assigned by the Federal Aviation Administration to the region’s airports are listed in TABLE 1. Ten of the airports are commercial airports, of which six had schedule commercial airline services in 2012, and one (March Inland Port, RIV) is a joint-use military airfield. AIRPORT PROFILES Because Southern California is a region with multiple airports that have overlapping Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) is the busiest airport located in the SCAG region in catchment areas, travelers to and from the region can choose among several airports for their terms of passenger volume.