Eugene W. Wu Harvard University the Development of East Asian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,* 1 State Specialist Institute of Arts, Rezervnyy Proyezd, D.12, Moscow, 121165 Russia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Combining with Wu Guanzhong's learning experience, this paper analyzes Chinese oil painting art characteristics in different periods, and the method of integrating traditional Chinese ink and wash painting language with the western modern design language in the aspects such as modelling, colour and composition. Wu Guanzhong successfully used western painting method to show the Oriental artistic conception, and formed unique composition views and forms. With the use of concise and simple colors and free-writing lines, the painter's personal emotions, thoughts and standpoint and deep understanding of life can be expressed. On the basis of in-depth research on the essence, connotation and thought of Chinese and Western art, Wu Guanzhong found the "junction" of the integration of Chinese and Western art. Keywords: Wu Guanzhong, Hangzhou Academy of Art, Ink and wash painting, Oil painting, Integration of Chinese and Western art. 1. INTRODUCTION Wu Guanzhong entered Hangzhou Academy of Art to study Chinese and Western paintings. In the Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), the People's school, he received direct guidance from teachers Artist, Art Educator, and Professor of the Academy such as Li Chaoshi, Fang Ganmin, and Pan of Arts and Design of Tsinghua University, used to Tianshou. Li Chaoshi and Fang Ganmin are both be an executive director of the Chinese Artists teachers who have returned from studying in Association, a member of the Standing Committee France, but their styles of painting are different. -

Tidal Resonance in the Gulf of Thailand

Ocean Sci., 15, 321–331, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-321-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Tidal resonance in the Gulf of Thailand Xinmei Cui1,2, Guohong Fang1,2, and Di Wu1,2 1First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao, 266061, China 2Laboratory for Regional Oceanography and Numerical Modelling, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266237, China Correspondence: Guohong Fang (fanggh@fio.org.cn) Received: 12 August 2018 – Discussion started: 24 August 2018 Revised: 1 February 2019 – Accepted: 18 February 2019 – Published: 29 March 2019 Abstract. The Gulf of Thailand is dominated by diurnal 1323 m. If the GOT is excluded, the mean depth of the rest tides, which might be taken to indicate that the resonant fre- of the SCS (herein called the SCS body and abbreviated as quency of the gulf is close to one cycle per day. However, SCSB) is 1457 m. Tidal waves propagate into the SCS from when applied to the gulf, the classic quarter-wavelength res- the Pacific Ocean through the Luzon Strait (LS) and mainly onance theory fails to yield a diurnal resonant frequency. In propagate in the southwest direction towards the Karimata this study, we first perform a series of numerical experiments Strait, with two branches that propagate northwestward and showing that the gulf has a strong response near one cycle per enter the Gulf of Tonkin and the GOT. The energy fluxes day and that the resonance of the South China Sea main area through the Mindoro and Balabac straits are negligible (Fang has a critical impact on the resonance of the gulf. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Inception of the Modern Public Health System in China

Virologica Sinica www.virosin.org https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-020-00269-4 www.springer.com/12250 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) PERSPECTIVE Inception of the Modern Public Health System in China and Perspectives for Effective Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases: In Commemoration of the 140th Anniversary of the Birth of the Plague Fighter Dr. Wu Lien-Teh 1,2 2 1,3,4 1,2 Qingmeng Zhang • Niaz Ahmed • George F. Gao • Fengmin Zhang Received: 30 January 2020 / Accepted: 28 June 2020 Ó Wuhan Institute of Virology, CAS 2020 Infectious diseases pose a serious threat to human health insights into the effective prevention and control of and affect social, economic, and cultural development. emerging infectious diseases as well as the current world- Many infectious diseases, such as severe acute respiratory wide pandemic of COVID-19, facilitating the improvement syndrome (SARS, 2013), Middle East respiratory syn- and development of public health systems in China and drome (MERS, 2012 and 2013), Zika virus infection around the globe. (2007, 2013 and 2015), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19, 2019), have occurred as regional or global epidemics (Reperant and Osterhaus 2017; Gao 2018;Li Etiological Investigation and Bacteriological et al. 2020). In the past 100 years, the world has gradually Identification of the Plague Epidemic established a relatively complete modern public health in the Early 20th Century system. The earliest modern public health system in China was founded by the plague fighter Dr. Wu Lien-Teh In September 1910, the plague hit the Transbaikal region of during the campaign against the plague epidemic in Russia and spread to Manzhouli, a Chinese town on the Northeast China from 1910 to 1911. -

Understanding the Relative Impacts of Natural Processes and Human Activities on the Hydrology of the Central Rift Valley Lakes, East Africa

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. (2015) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.10490 Understanding the relative impacts of natural processes and human activities on the hydrology of the Central Rift Valley lakes, East Africa Wondwosen M. Seyoum, Adam M. Milewski* and Michael C. Durham Department of Geology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA Abstract: Significant changes have been observed in the hydrology of Central Rift Valley (CRV) lakes in Ethiopia, East Africa as a result of both natural processes and human activities during the past three decades. This study applied an integrated approach (remote sensing, hydrologic modelling, and statistical analysis) to understand the relative effects of natural processes and human activities over a sparsely gauged CRV basin. Lake storage estimates were calculated from a hydrologic model constructed without inputs from human impacts such as water abstraction and compared with satellite-based (observed) lake storage measurements to characterize the magnitude of human-induced impacts. A non-parametric Mann–Kendall test was used to detect the presence of climatic trends (e.g. a decreasing or increasing trends in precipitation), while the Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) analysis was used to assess the long-term, inter-annual climate variability within the basin. Results indicate human activities (e.g. abstraction) significantly contributed to the changes in the hydrology of the lakes, while no statistically significant climatic trend was seen in the basin, however inter-annual natural climate variability, extreme dryness, and prolonged drought has negatively affected the lakes. The relative contributions of natural and human-induced impacts on the lakes were quantified and evaluated by comparing hydrographs of the CRV lakes. -

The EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy and Its Impact on Asia-Europe Relations

The EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy and Its Impact on Asia-Europe Relations Bart Gaens INTRODUCTION The EU is gradually adapting to a more uncertain world marked by increasing geo- political as well as geo-economic competition. Global power relations are in a state of flux, and in Asia an increasingly assertive and self-confident China poses a chal- lenge to US hegemony. The transatlantic relationship is weakening, and question marks are being placed on the future of multilateralism, the liberal world order and the rules-based global system. At least as importantly, China is launching vast con- nectivity and infrastructure development projects throughout Eurasia, sometimes interpreted as a geostrategic attempt to re-establish a Sinocentric regional order. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in particular, focussing on infrastructure devel- opment and investments in over 80 countries, including some within Europe, has been causing concern at regional as well as global levels. At the most recent BRI summit in April 2019 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China had signed new deals amounting to 64 billion USD, underscoring Beijing’s continuing cheque book diplomacy.1 It is clear that these ongoing dynamics potentially have important ramifica- tions for Europe’s own prosperity, in terms of trade and economy but also security. Overall however, the EU has been slow to react, in particular in formulating a re- sponse to connectivity challenges. In September 2018 the EU published its first coordinated attempt to formulate the European vision on connectivity and infra- structure development, in the form of a European connectivity strategy for Asia, officially entitled a Joint Communication on “Connecting Europe and Asia – building blocks for an EU strategy”. -

China's Influence on Conflict Dynamics in South Asia

USIP SENIOR STUDY GROUP FINAL REPORT China’s Influence on Conflict Dynamics in South Asia DECEMBER 2020 | NO. 4 USIP Senior Study Group Report This report is the fourth in USIP’s Senior Study Group (SSG) series on China’s influence on conflicts around the world. It examines how Beijing’s growing presence is affecting political, economic, and security trends in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. The bipartisan group was comprised of senior experts, former policymakers, and retired diplomats. They met six times by videoconference over the course of 2020 to examine how an array of issues—from military affairs to border disputes, trade and development, and cultural issues—come together to shape and be shaped by Chinese involvement. The group members drew from their deep individual experiences working in and advising the US government to generate a set of top-level findings and actionable policy recommen- dations. Unless otherwise sourced, all observations and conclusions are those of the SSG members. Cover illustration by Alex Zaitsev/Shutterstock The views expressed in this report are those of the members of the Senior Study Group alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org First published December 2020. -

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies Organized by With support from from PRIMUS Visual Histories of South Asia Foreword by Christopher Pinney Edited by Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes and Marcus Banks This book wishes to introduce the scholars of South Asian and Indian History to the in-depth evaluation of visual research methods as the research framework for new historical studies. This volume identifies and evaluates the current developments in visual sociology and digital anthropology, relevant to the study of contemporary South Asian constructions of personal and national identities. This is a unique and excellent contribution to the field of South Asian visual studies, art history and cultural analysis. This text takes an interdisciplinary approach while keeping its focus on the visual, on material cultural and on art and aesthetics. – Professor Kamran Asdar Ali, University of Texas at Austin 978-93-86552-44-0 u Royal 8vo u 312 pp. u 2018 u HB u ` 1495 u $ 71.95 u £ 55 Hidden Histories Religion and Reform in South Asia Edited by Syed Akbar Hyder and Manu Bhagavan Dedicated to Gail Minault, a pioneering scholar of women’s history, Islamic Reformation and Urdu Literature, Hidden Histories raises questions on the role of identity in politics and private life, memory and historical archives. Timely and thought provoking, this book will be of interest to all who wish to study how the diverse and plural past have informed our present. Hidden Histories powerfully defines and celebrates a field that has refused to be occluded by majoritarian currents. – Professor Kamala Visweswaran, University of California, San Diego 978-93-86552-84-6 u Royal 8vo u 324 pp. -

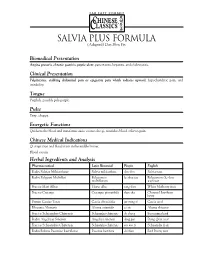

Salvia Plus Formula (Adapted) Dan Shen Yin

Far East Summit ®® Salvia Plus Formula (Adapted) Dan Shen Yin Biomedical Presentation Angina pectoris , chronic gastritis , peptic ulcer , pancreatitis, hepatitis, and cholecystitis. Clinical Presentation Palpitations , stabbing abdominal pain or epigastric pain which radiates upward , hypochondriac pain, and irritability. Tongue Purplish, possibly pale-purple. Pulse Deep, choppy. Energetic Functions Quickens the blood and transforms stasis, courses the qi, nourishes blood, relieves pain. Chinese Medical Indications Qi stagnation and blood stasis in the middle burner. Blood vacuity. Herbal Ingredients and Analysis Pharmaceutical Latin Binomial Pinyin English Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae Salvia miltiorrhiza dan shen Salvia root Radix Polygoni Multiflori Polygonum he shou wu Polygonum (he shou multiflorum wu) root Fructus Mori Albae Morus alba sang shen White Mulberry fruit Fructus Crataegi Crataegus pinnatifida shan zha Chinese Hawthorn berry Semen Cassiae Torae Cassia obtusifolia jue ming zi Cassia seed Rhizoma Alismatis Alisma orientale ze xie Alisma rhizome Fructus Schisandrae Chinensis Schisandra chinensis du zhong Eucommia bark Radix Angelicae Sinensis Angelica sinensis dang gui Dong Quai root Fructus Schisandrae Chinensis Schisandra chinensis wu wei zi Schisandra fruit Radix Rubrus Paeoniae Lactiflorae Paeonia lactifora chi shao Red Peony root Salvia Plus (cont.) Herbal Ingredients and Analysis (cont.) Pharmaceutical Latin Binomial Pinyin English Radix Scutellariae Baicalensis Scutellaria huang qin Scutellaria (huang qin) baicalensis root Lignum Santali Albi Santalum album tan xiang Sandalwood wood Fructus Amomi Amomum villosum sha ren Cardamon Amomum (sha ren) fruit Radix Aucklandiae Lappae Aucklandia lappa mu xiang Saussurea root Salvia nourishes blood, quickens the blood, dispels stasis, and relieves pain. Sandalwood, Cardamon and Saussurea rectify qi. Together these medicinals provide the main action of the formula by quickening blood, transforming stasis and rectifying qi. -

An Evolving ASEAN: Vision and Reality

Menon • Lee An Evolving ASEAN Vision and Reality The formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in was originally driven by political and security concerns In the decades that followed ASEAN’s scope evolved to include an ambitious and progressive economic agenda In December the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was formally launched Although AEC has enjoyed some notable successes the vision of economic integration has yet to be fully realized This publication reviews the evolution of ASEAN economic integration and assesses the major achievements It also examines the challenges that emerged during the past decade and provides recommendations on how to overcome them About the Asian Development Bank AN EVOLVING ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous inclusive resilient and sustainable Asia and the Pacifi c while sustaining its e orts to eradicate extreme poverty Established in it is owned by members— from the region Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue loans equity investments guarantees grants and technical assistance ASEAN: AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY VISION Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBER AND REALITY ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org 9 789292 616946 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBEr 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

Securing Canada's Place in Asia-Pacific

STANDING SENATE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE SECURING CANADA’S PLACE IN ASIA-PACIFIC: A FOCUS ON SOUTHEAST ASIA June 2015 Ce rapport est aussi disponible en français. Des renseignements sur le comité sont donnés sur le site : www.senate-senat.ca/AEFA.asp. Information regarding the committee can be obtained through its web site: www.senate-senat.ca/AEFA.asp. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... iii THE COMMITTEE .................................................................................................................. v ORDER OF REFERENCE ..................................................................................................... vii LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................ 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 3 RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 11 PART I: CANADA AND THE ASIA-PACIFIC ................................................................... 15 A. A Vibrant and Diverse Region ...............................................................................