An Improved Cloud Gap-Filling Method for Longwave Infrared Land Surface Temperatures Through Introducing Passive Microwave Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Sensors for Applications

OVERVIEW OF SENSORS FOR APPLICATIONS Deepak Putrevu Head, MTDD/AMHTDG EM SPECTRUM Visible 0.4-0.7μm Near infrared (NIR) 0.7-1.5μm Optical Infrared Shortwave infrared (SWIR) 1.5-3.0μm Mid-wave infrared (MWIR) 3.0-8.0μm (OIR) Region Longwave IR(LWIR)/Thermal IR(TIR) 8.0-15μm Far infrared (FIR) Beyond15μm Gamma Rays X Rays UV Visible NIR SWIR Thermal IR Microwave P-band: ~0.25 – 1 GHz Microwave Region L-band: 1 -2 GHz S-band: 2-4 GHz •Sensors are 24x365 C-band: 4-8 GHz •Signal data characteristics X-band: 8-12 GHz unique to the microwave region of the EM spectrum Ku-band: 12-18 GHz K-band: 18-26 GHz •Response is primarily governed by geometric Ka-band: 26-40 GHz structures and hence V-band: 40 - 75 GHz complementary to optical W-band: 75-110 GHz imaging mm-wave: 110 – 300GHz Basic Interactions between Electromagnetic Energy and the Earth’s Surface Incident Power reflected, ρP Reflectivity: The fractional part of the radiation, P incident radiation that is reflected by the surface. Power absorbed, αP Absorptivity: the fractional part of the = Power emitted, εP incident radiation that is absorbed by the surface. Power transmitted, τP Emissivity: The ratio of the observed flux emitted by a body or surface to that of a P= Pr + Pt + Pa blackbody under the same condition. 푃 푃 푃 푟 + 푡 + 푎 = 1 푃 푃 푃 Transmissivity: The fractional part of the ρ + τ + α =1 radiation transmitted through the medium. At thermal equilibrium, absorption and emission are the same. -

Newsgathering Transmission Techniques

NEWSGATHERING TRANSMISSION TECHNIQUES Ennes Workshop – Miami, FL March 8, 2013 Kevin Dennis Regional Sales Manager 2 Vislink is Built on a Firm Foundation 3 Presentation Outline • Advancements in video encoding technology – H.264 versus MPEG-2 • Advancements in licensed microwave technology – Implementing HD/SD H.264 encoding – Modulation, FEC, high power Linear Amps • Advancements in bandwidth capacity of public access networks (Cellular and Wi-Fi) – 3G, 4G, LTE, WiMax – HD/SD Bonded Cellular Video Transmission • Comparison of strengths and weaknesses of licensed microwave transmission versus public network transmissions Newsgathering Transmission Techniques • Advancements in video encoding technology • Advancements in licensed microwave technology • Advancements in bandwidth capacity of public access networks (Cellular and Wi-Fi) • Comparison of strengths and weaknesses of licensed microwave transmission versus public network transmissions H.264 (MPEG-4 AVC / Part10) versus MPEG-2 • H.264/MPEG-4 AVC is a block-oriented motion-compensation based codec standard • First version of the standard was completed in 2003 • H.264 video compression is significantly more efficient than MPEG-2 encoding providing two-fold improvement as compared to MPEG-2 • H.264 HD encoding not excessively expensive to implement as compared to first MPEG-2 encoders H.264 (MPEG-4 AVC) vs. MPEG-2 H.264 is approximately twice as efficient as MPEG-2 Video quality comparison of H.264 (solid blue line with squares) and MPEG-2 (dotted red line with circles) as a function of bit rate compared to 100 Mbps source material. H.264 (MPEG-4 AVC) vs. MPEG-2 Low Motion Video - there is very little video quality difference between H.264 and MPEG-2 Video Images posted by Jan Ozer, Video Technology Instructor H.264 (MPEG-4 AVC) vs. -

Overcoming Barriers to Providing Mobile Coverage Everywhere

WHITE PAPER Overcoming Barriers to Providing Mobile Coverage Everywhere Published by © 2018 Introduction New international efforts to tackle digital While connecting the unconnected is an inequality have made expanding broadband important driver for expanding coverage, it’s not infrastructure a global priority. The United the only one. Operators in developing and Nations’ Broadband Commission for Sustainable developed countries are under pressure to build Development recently set ambitious targets for out infrastructure for a variety of business and 2025 to connect the remaining half of the regulatory reasons. Depending on the market, world’s population to the Internet. The goals operator requirements include meeting coverage include a mandate for all countries to establish obligations attached to spectrum licenses, funded national broadband plans, or broadband providing national emergency or disaster universal service requirements, as well as making recovery services, reducing roaming and leased affordable broadband services available in line costs and growing their customer base. developing countries (costing less than 2% of monthly gross national income per capita) by 2025. Mobile Internet connectivity will be key to “Mobile Internet achieving these broadband sustainable development goals that will bring economic and connectivity is key to social benefits to billions of people worldwide. There are two categories of unconnected achieving sustainable people: those that are covered by mobile broadband, 3G or 4G, infrastructure but do not development goals that use Internet services and those with no access to mobile networks at all. According to the will bring economic and GSMA, about 3.3 billion people are covered but not connected, while 1 billion people are not social benefits to billions covered. -

Digital Radio Broadcasting Network in the Arctic Region

______________________________________________________PROCEEDING OF THE 24TH CONFERENCE OF FRUCT ASSOCIATION Digital Radio Broadcasting Network in the Arctic Region Oleg Varlamov, Vladimir Varlamov, Anna Dolgopyatova Moscow Technical University of Communications and Informatics Moscow, Russia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Successful economic development of the Arctic 81°), where the geostationary orbit (GEO) is observed very low zone is impossible without creating a continuous information field above the horizon and only a small portion of it is visible, that covers its entire territory and is available not only at where the satellites of the required operator are not always stationary objects, but primarily in moving vehicles - ships, cars, present, providing information fields using satellites located on airplanes, etc. This information field must consist from the GEO is not possible. Approximately from 81 ° to the poles transmission of audio information (broadcasting programs), data (weather maps, ice conditions, etc.), navigation signals, alerts and GEO from the surface of the Earth is not visible even information about emergencies, and must be reserved from theoretically. different sources. As a backup system (and in the coming years, The most promising for the formation of the main the main one) it is advisable to use single-frequency digital information field in the Arctic zone can be considered satellite broadcasting networks of the Digital Radio Mondiale standard in the low frequency range. This is the most economical system for systems in highly elliptical (HEO) or low Earth (LEO) orbits. covering remote areas. For the use of these systems, have all the At the same time, the high cost of such systems, the long period necessary regulatory framework and standard high-efficiency of infrastructure deployment and the limited lifespan, combined radio transmitters. -

Microwave Receivers with Direct Digitization

Microwave Receivers with Direct Digitization Dmitri E. Kirichenko, Timur V. Filippov, and Deepnarayan Gupta HYPRES, Elmsford, NY, 10532, U.S.A. Abstract — Superconductor analog-to-digital converters integrated circuit (IC) technology with Niobium (Nb) (ADCs) and ultrafast digital circuitry enable processing of Josephson junctions (JJs), currently offer the best solution. microwave signals entirely in the digital domain. We have Superconductor ICs combine high-linearity, wideband ADCs designed and demonstrated a wide variety of continuous-time bandpass delta-sigma modulators using Josephson junction [2] and ultrafast digital logic, called rapid single flux quantum comparators. Featuring sampling frequencies up to 30 GHz, (RSFQ). A family of superconductor digital-RF receiver single-chip digital receivers have been demonstrated by (called ADR) chips (Fig. 1), comprising an ADC and a digital connecting a rapid single flux quantum (RSFQ) digital circuitry channelizer circuit, performing digital down-conversion and with these ADCs. These receiver chips, cooled to 4 K by cryogen- filtering, have been demonstrated. Notably, a digital-RF free refrigerators, have been used with room-temperature digital processors to demonstrate reception of microwave signals for X- receiver system, comprising a cryocooled ADR chip, was band satellite communications and Link-16 data links. To date, demonstrated reception of live satellite communication signals the highest frequency of direct digitization is 21 GHz for satellite in the X-band (7.25-7.75 GHz) [3]. In this paper, we focus on communication. We report recent advances in ADC design to ADCs for various microwave frequency bands ranging from 1 obtain higher dynamic range. GHz to 21 GHz. Index Terms — Analog-to-digital converter, RSFQ, cryogenic, Digital Output (I) SATCOM. -

High-Frequency Radiowa Ve Probing of the High-Latitude Ionosphere

RAYMOND A. GREENWALD HIGH-FREQUENCY RADIOWAVE PROBING OF THE HIGH-LATITUDE IONOSPHERE During the past several years, a program of high-frequency radiowave studies of the high-latitude ionosphere has been developed in the APL Space Department. Studies are now being conducted on the formation and motion of high-latitude ionospheric electron density irregularities, using a sophisti cated high-frequency radar system installed at Goose Bay, .Labrador. The radar antenna is also being used to receive signals from a beacon transmitter located at Thule, Greenland. This information is providing a better understanding of the spatial and temporal variability of high-latitude propagation channels and their relationship to disturbances in the magnetosphere-ionosphere system . INTRODUCTION turbances prior to their impingement on the magneto At altitudes above 100 kilometers, the atmosphere sphere is quite limited. Therefore, we still have only of the earth gradually changes from a predominantly limited success in forecasting sudden changes in the neutral medium to an increasingly ionized gas or plas high-latitude ionosphere and consequently in high ma. The ionization is caused chiefly by a combination latitude radiowave propagation. of solar extreme ultraviolet radiation and, at high lati In order for space scientists to obtain a better un tudes, particle precipitation from the earth's magne derstanding of the various interactions occurring tosphere. Because of its ionized nature between 100 among the solar wind, the magnetosphere, and the ion and 1000 kilometers, this part of the atmosphere is osphere, active measurement programs are conduct commonly referred to as the ionosphere. In this re ed in all three regions. -

Portable Shortwave Receivers

Portable Shortwave Receivers ● Longwave, AM, FM and Shortwave ELITE SATELLIT ● VHF Air Band ● HD Radio Reception ● RDS Display ● Superior Sensitivity and Selectivity ● Dual Conversion Design ● Huge 5.7 Inch Backlit Display ● Drift-free Digital Phase Lock Loop ● Direct Frequency and Band Entry ● Single Sideband Synchronous Detector ● Selectable Bandwidths ● High Dynamic Range ● Dual Programmable Clocks ● Dual Event Programmable Timers ● Stereo Line Level Input ● Stereo Line Level Output ● Earphone Jack ● Separate Bass and Treble Controls ● Adjustable AGC: Fast or Slow ● Telescopic Antenna AM/FM/SW ● Battery (4xD) or Included AC Adapter ● Scan and Search ● 1700 Total Memories (500 alphanumeric) ● Deluxe Carry Bag The Elite Satellit is simply the finest full-sized portable in the world. The Elite Satellit is an elegant confluence of performance, features and capabilities. The look, feel and finish of this radio is superb. The solid, quality feel is second to none. The digitally synthesized, dual conversion shortwave tuner covers all long wave, mediums wave (AM) and shortwave frequencies. HD Radio improves audio fidelity and adds additional programming without a subscription fee. Adjacent frequency interference can be minimized or eliminated with a choice of three bandwidths [7.0, 4.0, 2.5 kHz]. The sideband selectable Synchronous AM Detector further minimizes adjacent frequency interference and reduces fading distortion of AM signals. IF Passband Tuning is yet another advanced feature that functions in AM and SSB modes to reject interference. AGC is selectable at fast or slow. High dynamic range permits the detection of weak signals in the presence of strong signals. All this coupled with great sensitivity will bring in stations from every part of the globe. -

Hans Knot International Radio Report April 2016 Welcome to Another

Hans Knot International Radio Report April 2016 Welcome to another edition of the International Radio Report. Thanks all for your e mails, memories, photos, questions and more. Part of the report is what was left after the March edition was totally filled and so let’s go with this edition in which first there’s space for a story I wrote last months after again doing some research: ‘Ronan O’Rahilly, Georgie Fame and the Blue Fames. Where it really went wrong!’ On this subject I’ve written before but let’s go back in time and also add some new facts to it: ‘Was Ronan O’Rahilly the manager of Georgie Fame?’ I can tell you there was a problem with an important instrument. When in April 1964 Granada Television came with an edition of the ‘World in action’ series, which was a production from Michael Hodges, they informed the television public about a new form of Piracy, the watery pirates. Two radio ships bringing music and entertainment under the names of Radio Caroline and Radio Atlanta. Radio Caroline was the first 20th century Pirate off the British coast with programs, at that stage, for 12 hours a day. Interviews with the Caroline people were made in the offices of Queen Magazine in the city of London and included – among others – Jocelyn Stevens and the then 23-year old Irish Ronan O’Rahilly. During this documentary it became known, which we would also read in several newspapers in the then following weeks, that Ronan O’Rahilly had started his radiostation Caroline as he couldn’t get his artists played on stations like Radio Luxembourg. -

Downloaded 09/25/21 09:30 PM UTC

1434 JOURNAL OF HYDROMETEOROLOGY VOLUME 9 NASA Cold Land Processes Experiment (CLPX 2002/03): Local Scale Observation Site ϩ JANET HARDY,* ROBERT DAVIS,* YEOHOON KOH,* DON CLINE, KELLY ELDER,# RICHARD ARMSTRONG,@ HANS-PETER MARSHALL,@ THOMAS PAINTER,& ϩϩ GILLES CASTRES SAINT-MARTIN,** ROGER DEROO,** KAMAL SARABANDI,** TOBIAS GRAF, ϩϩ TOSHIO KOIKE, AND KYLE MCDONALD## *Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, Engineer Research and Development Center, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hanover, New Hampshire ϩNOAA/NWS/National Operational Hydrologic Remote Sensing Center, Chanhassen, Minnesota #USDA Forest Service, Fort Collins, Colorado @University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado &University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah **University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan ϩϩUniversity of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan ##NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California (Manuscript received 12 January 2007, in final form 19 March 2008) ABSTRACT The local scale observation site (LSOS) is the smallest study site (0.8 ha) of the 2002/03 Cold Land Processes Experiment (CLPX) and is located within the Fraser mesocell study area. It was the most intensively measured site of the CLPX, and measurements here had the greatest temporal component of all CLPX sites. Measurements made at the LSOS were designed to produce a comprehensive assessment of the snow, soil, and vegetation characteristics viewed by the ground-based remote sensing instruments. The objective of the ground-based microwave remote sensing was to collect time series of active and passive microwave spectral signatures over snow, soil, and forest, which is coincident with the intensive physical characterization of these features. Ground-based remote sensing instruments included frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radars operating over multiple microwave bandwidths; the Ground-Based Mi- crowave Radiometer (GBMR-7) operating at channels 18.7, 23.8, 36.5, and 89 GHz; and in 2003, an L-, C-, X- and Ku-band scatterometer radar system. -

Satellite Backhaul Vs Terrestrial Backhaul: a Cost Comparison

Satellite Backhaul vs Terrestrial Backhaul: A Cost Comparison A perfect storm 3 Network deployment comparison 4 Semi-rural terrestrial backhaul deployment 4 Rural terrestrial backhaul deployment 5 TCO Comparison 6 July 2015 LTE Backhaul over Satellite p. 2 ©2015 Gilat Satellite Networks Ltd. All rights reserved. A perfect storm The mobile industry and the satellite industry have worked in parallel for decades, occasionally targeting the same market but mostly not. While mobile operators satisfied the vast demand for personalized on- the-move connectivity in population centers, satellite focused on connectivity in remote regions. But then - two phenomena converged. One was that mobile traffic became increasingly data-driven. This meant that the throughput requirements for mobile networks would need to grow exponentially. As the diagram below shows, using the United States as an example, mobile network traffic is expected to double between 2015 and 2017. Figure 1: Mobile Traffic Forecasts The proliferation of data over mobile has spurred the adaption of higher communications standards such as 4G/LTE. While these standards have not yet been implemented everywhere, they are surely on their way, and standards with even higher capacity – 5G and beyond – will follow. At the same time, advances in the satellite industry have slashed the cost of bandwidth. High-Throughput Satellites (HTS) offer significantly increased capacity, reducing bandwidth costs by as much as 70 July 2015 LTE Backhaul over Satellite p. 3 ©2015 Gilat Satellite Networks Ltd. All rights reserved. percent. This breakthrough has helped position satellite communication as a cost-effective alternative for delivering broadband while reducing operating expenses. -

Where's the Interference? Finding out Helps Improve Wi-Fi Performance

Newsletter Article Where’s the Interference? Finding Out Helps Improve Wi-Fi Performance and Security What do microwave ovens, cordless phones, and wireless video surveillance cameras have in common? They all can create interference that affects the performance, reliability, and security of a school’s wireless network. “When schools limited their use of Wi-Fi to the library and administration areas, an occasional dropped connection caused by interference from a 2.4 GHz phone or a microwave oven wasn’t much of a problem,” says Sylvia Hooks, senior manager for mobility solutions at Cisco.. “It’s a different story when schools provide campuswide wireless connectivity for students, faculty, and staff.” In fact, many K-12 districts are in the process of expanding their wireless networks to provide high-performance 802.11n wireless for high-speed Internet access, web-based student information systems, and video for classroom learning and district meetings. Quickly Find Interference Sources The complication is that Wi-Fi operates in an unlicensed spectrum, shared by equipment ranging from cordless phones to baby monitors. Until recently, if teachers or students complained about wireless network performance, school IT teams could not readily identify the types and locations of the devices causing the interference, especially if the interference was intermittent. And when IT teams did find the source, which could be as benign as a neighboring building’s wireless network, mitigating the problem took specialized skills and time, both in short supply within school IT teams stretched thin. Easily Visualize Wireless Air Quality Now school IT teams have an easy way to visualize the wireless spectrum. -

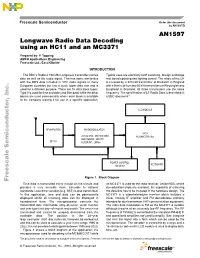

AN1597 Longwave Radio Data Decoding Using an HC11 and an MC3371

Freescale Semiconductor, Inc... microprocessor used for decoding is the MC68HC(7)11 while microprocessor usedfordecodingisthe MC68HC(7)11 2023. and 1995 between distinguish Itisnotpossible to 2022. and thiscanbeusedtocalculate ayearintherange1995to beworked out cyclecan,however, leap–year/year–start–day data.Thepositioninthe28–year available andcannotbeuniquelydeterminedfromthe transmitted and yeartype)intoday–of–monthmonth.Theisnot dateinformation(day–of–week,weeknumber transmitted the form.Themicroprocessorconverts hexadecimal displayed whilst allincomingdatacanbedisplayedin In thisapplication,timeanddatecanbepermanently standards. Localtimevariation(e.g.BST)isalsotransmitted. provides averyaccurateclock,traceabletonational Freescale AMCU ApplicationsEngineering Topping Prepared by:P. This documentcontains informationonaproductunder development. This to thecompanyleasingitforuseinaspecificapplication. available blocks areusedcommerciallywhereeachblockis other 0isusedfortimeanddate(andfillerdata)whilethe Type purpose.There are16datablocktypes. used foradifferent countriesbuthasamuchlowerdatarateandis European with theRDSdataincludedinVHFradiosignalsmany aswelltheaudiosignal.Thishassomesimilarities data using an HC11 and Longwave an Radio MC3371 Data Decoding Figure 1showsablock diagramoftheapplication; Figure data is transmitted every minuteontheand Time The BBC’s Radio4198kHzLongwave transmittercarries The BBC’s Ltd.,EastKilbride RF AMPLIFIERDEMODULATOR FM BF199 FILTER/INT.: LM358 FILTER/INT.: AMP/DEMOD.: MC3371 LOCAL OSC.:MC74HC4060