A Walk from Charing Cross to St Paul's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worldwide Hotel Listing May 2008

WORLDWIDE HOTEL LISTING MAY 2008 www.PreferredHotelGroup.com Master Chain Code: PV Preferred Hotels & Resorts (PH) Preferred Boutique (BC) Summit Hotels & Resorts (XL) Sterling Hotels (WR) www.PreferredHotels.com www.Preferred-Boutique.com www.SummitHotels.com www.SterlingHotels.com AFRICA GHANA MOROCCO SOUTH AFRICA Accra Marrakech Cape Town Fiesta Royale Hotel (WR) Es Saadi Hotel (WR) The Peninsula All-Suite Hotel (XL) Es Saadi Palace & Villas (PH) KENYA Le Pavillon du Golf (BC) Nairobi Les Jardins d’Ines (BC) The Sarova Stanley (XL) Palmeraie Golf Palace & Resort (PH) ASIA PACIFIC AustrALIA FRENCH PolyNESIA Yokohama Palm Cove Bora Bora Yokohama Royal Park Hotel (XL) Double Island (BC) Bora Bora Cruises (BC) KOREA Sydney INDIA Seoul Star City Hotel and Apartments (XL) Bharatphur Imperial Palace, Seoul (XL) CAMBODIA The Bagh (BC) The Shilla Seoul (PH) Siem Reap Hyderabad MALAysiA The Sothea Courtyard (Opening July 08) (BC) Leonia (WR) Kuala Lumpur CHINA Jaipur Hotel Istana (XL) Samode Palace (PH) Beijing New ZEALAND The Opposite House (Opening July 08) (PH) New Delhi The Imperial New Delhi (PH) Queenstown Guangzhou Azur (BC) DongFang Hotel (XL) The Metroplitan Hotel New Delhi (XL) Hong Kong Udaipur PHILIPPINES Harbour Plaza Hong Kong (XL) Devi Garh (PH) Manila Regal Airport Hotel (XL) INDONESIA Manila Hotel (XL) Regal Hongkong Hotel (XL) Jakarta SINGAPORE Regal Kowloon Hotel (WR) Hotel Mulia Senayan (PH) Singapore Regal Oriental Hotel (WR) JAPAN Goodwood Park Hotel (PH) Regal Riverside Hotel (WR) Sapporo Royal Plaza on Scotts (XL) The -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

2019 Guest Book

16 –17 OCTOBER 2018 OLYMPIA LONDON PRESENTED BY Insurance Brokers 2019 GUEST BOOK YOUR REVIEW OF THE UK’S LARGEST AND MOST ESTABLISHED BUSINESS EVENT FOR THE HOTEL COMMUNITY INDEPENDENT HOTEL SHOW 2019 GUEST DEMOGRAPHICS TOTAL VISITORS 6316 COMPANY ACTIVITY TRAVELLED FROM Hotel 59% London 35% Opening a new hotel 6% South East 29% Guesthouse / B&B 7% South West 8% Pub / Restaurant with rooms 3% Midlands 7% Serviced apartments 6% North 7% Other accommodation 12% East 2% Industry supporters / press 7% Wales 2% Scotland 2% Overseas 8% % % % % 83 80 89 91 intend to do business with one of visitors have direct of visitors said they of visitors will be or more of the exhibitors purchasing authority would recommend the returning in 2020 they met at the show within show to a friend the next 12 months or colleague ACCOMMODATION SIZE COMPANY STATUS 1–10 rooms 20% Independent 80% 11–25 rooms 18% Group owned 13% 26–50 rooms 19% Other 7% 50–100 rooms 18% 100+ rooms 25% 2 INDEPENDENTHOTELSHOW.CO.UK INDEPENDENT HOTEL SHOW 2019 THE SUPPLIER EXPERIENCE TOTAL EXHIBITORS 337 65% OF EXHIBITORS RE- BOOKED ONSITE FOR 2020 “The Independent Hotel Show is one of the “The Independent Hotel Show gave us “The Independent Hotel Show is a most important hotel shows in the country. the opportunity to engage face to face with key event in our calendar. There is no It attracts a very diverse group of people, a targeted audience and showcase our other trade show that offers the same level not just independent hoteliers, but also the products to key decision makers. -

1662 Hot Post Office London Hot

1662 HOT POST OFFICE LONDON HOT HOT WATER ENGINEERS-continued. Carlton h. (Jacques Krnemer, manager), Pall • GROSYENOR H. (THE) (The Gordon Hotels Maisonettes (The), f.h. (Carlo Antonio An Troy F. & Co. 194 & 1.96 Finchley road NW mall SW & Haymarket SW Ltd.), Buckingham palace road SW; tonelli, proprietor), 28 & 30 De V ere gar Twelve Hours Stove SyndicateLtd.258 Vaux Carter's h. Mrs. Annie Hug, 14 & 15 Albc adjoining Victoria station; dens, Kensington W hall bridge road SW marle street W central for Belgravia, Mandeville f.h. 8 & 10 Mandeville place W Wailer Thomas & Oo.46 Fish street hill E C & Cavendish h. Mrs. Rosa Lewi8, 81 to 83 Westminster & all parts Mansfleld h. Alfred Thomas·& Albert Edward 1 Wolseley street, Dockhead SE Jermyn street SW & 18 Duke street, St. of London; Tel. No. 9061 Gerrard; Davies, 135 Mansfleld road, Haverstock Werner, Pfieiderer & Perkins Ltd. Kingsway James' SW TA "Grosvenor Hotel, London" hill NW house, Kingsway WC CHARING CROSS HOTEL & RESTAUR· Grosvenor Court Hotel, 89 Davies street W Marsball Thompson's h. Arthur John Turk, Whitby Bros. 29, :!0 & :lOA, Eagle street WC & ANT(S.E.R.) (E.Neuschwander, manager), Guildhall tavern (Pimm's Ltd. proprietors), 28 & 29 Cavendish square W 124 Higbgate road NW Strand WC 81 & 83 GreshR.m st E C & 22 King street, McHropole h. (The GQnlon Hotels Ltd. White Henry & Sons, 55 Frith street, Soho W Charterhouse h. Charterhonse square E C Oheapside E C proprietors), Northumberland avenue WC ; Williams James 18 St. Ann's terrace, St. Cheshire Cheese h. Holloway & Myers, Half Moon h. -

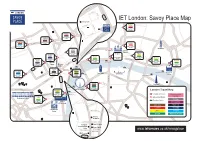

SP Location Map New 16.08.12

ND RA ST OW Y R S O A AV V S O Y A301 S T IET London: Savoy Place Map Savoy Hotel S A AY V Barbican Y W O AVO Y S H IL L Walking Distance C 29 mins A R T IN G E L C Holborn N LA Y P T VO EN SA M T NK Walking Distance EN BA Tottenham M M 7 mins K E Court Road N IA BA R M TO E IC IA V Oxford Circus Walking Distance R TO D ST 17 mins IC St. Paul’s OXFOR V Walking Distance Walking Distance 27 mins 22 mins ET ST The Gherkin Covent FLE Garden City Thameslink St. Paul’s R E G Cathedral Mansion E Walking Distance N Blackfriars House T 9 mins Leicester S T Square Temple Walking Distance Walking Distance Monument 15 mins UPP 28 mins Walking Distance ER THA Piccadilly MES S Circus 11 mins A4 Walking Distance T Tower Hill 10 mins Blackfriars Pier Walking Distance Leicester 32 mins ND Walking Distance RA W E Walking Distance Square Nelson’s T A G S T D L 17 mins I OW 40 mins E ER TH Column R R AMES ST B L O K O R Savoy Pier B Bankside Pier A Charing R London W A4 Cross ID H Charing Cross Embankment G T Green Park E U O Tower Millenium Pier S Tower Of Walking Distance Oxo Tower Tate Modern 7 mins T Walking Distance Festival Pier London L N Walking Distance AL D London Bridge City Pier M E 6 mins L R S E 25 mins L A3212 M OU A S G P K T R H D N W I A A A I RK R B B R S LY L T DI AL M F R E K E A M C E C A W C H I I T A P O R L T London B O T Waterloo Waterloo East C I The Shard V St. -

Background to the Formation of the Savoy Gastronomes Founded 1971

Background to the formation of The Savoy Gastronomes Founded 1971 Re-compiled by Founding Member Julian L Payne August 2014 Aim of the Amicale is “To foster the spirit of the Savoy Reception” Historical note To put this aim into context it is necessary to understand the background of the functioning of the Reception Office in earlier years. This department of the hotel had manual control over every arrival, departure and room allocation of the 526 rooms that the Savoy had. It was often the final department that aspiring hoteliers reached as part of their management training, having been through many other stages to reach this pinnacle. The daytime dress code was very formal. Stiff collars, subdued ties, waistcoats, tailcoats and pinstriped trousers, black lace up shoes and black socks. At 4.30 pm when the evening brigade arrived it was Black Tie, dinner jacket, with the two Night Managers wearing the same when they arrived at 11.30 pm. Those on the late brigade often met up in Southampton Street, just across the road, for a cup of tea from a small mobile tea stall and if the evening had been personally financially rewarding a bacon sandwich. Tips were pooled by the whole brigade and divided out at the end of the week on a points system. Brigades comprised of three or four young men who stayed in the department for at least a year; there was a very defined hierarchy with the “lowest” entrant stuck for hours “under the stairs” sharpening pencils or answering the very busy telephones. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

Historical Perspectives of Urban Drainage

Historical Perspectives of Urban Drainage Steven J. Burian* and Findlay G. Edwards* *Assistant Professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, University of Arkansas, 4190 Bell Engineering Center, Fayetteville, AR 72701 USA, Phone: (479) 575-4182; [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract Historically, urban drainage systems have been viewed with various perspectives. During different time periods and in different locations, urban drainage has been considered a vital natural resource, a convenient cleansing mechanism, an efficient waste transport medium, a flooding concern, a nuisance wastewater, and a transmitter of disease. In general, climate, topography, geology, scientific knowledge, engineering and construction capabilities, societal values, religious beliefs, and other factors have influenced the local perspective of urban drainage. For as long as humans have been constructing cities these factors have guided and constrained the development of urban drainage solutions. Historical accounts provide glimpses of many interesting and unique urban drainage techniques. This paper will highlight several of these techniques dating from as early as 3000 BC to as recently as the twentieth century. For each example discussed, the overriding perspective of urban drainage for that particular time and place is identified. The presentation will follow a chronological path with the examples categorized into the following four time periods: (1) ancient civilizations, (2) Roman Empire, (3) Post-Roman era to the nineteenth century, and (4) modern day. The paper culminates with a brief summary of the present day perspective of urban drainage. Introduction The relation of modern engineering to ancient engineering is difficult to comprehend considering that modern engineering is so highly specialized and technologically advanced. -

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission 1 Introduction ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’, 2017, by Simon Roberts, commissioned by Tideway This is a temporary commission located on the Thames Tideway Tunnel construction site hoardings at Victoria Embankment, 2017-19. Responding to the rich heritage of the Victoria Embankment, Simon Roberts has created a metaphorical ‘cabinet of curiosities’ along two 25- metre foreshore hoardings. Roberts describes his approach as an ‘aesthetic excavation of the area’, creating an artwork that reflects the literal and metaphorical layering of the landscape, in which objects from the past and present are juxtaposed to evoke new meanings. Monumental statues are placed alongside items that are more ordinary; diverse elements, both man-made and natural, co-exist in new ways. All these components symbolise the landscape’s complex history, culture, geology, and development. Credits Artist: Simon Roberts Images: details from ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’ © Simon Roberts, 2017. Archival images: © Copyright Museum of London; Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum; Wellcome Library, London; © Imperial War Museums (COM 548); Courtesy the Parliamentary Archives, London. Special thanks due to Luke Brown, Demian Gozzelino (Simon Roberts Studio); staff at the Museum of London, British Museum, Houses of Parliament, Parliamentary Archives, Parliamentary Art Collection, Wellcome Trust, and Thames21; and Flowers Gallery London. 1 About the Artist Simon Roberts (b.1974) is a British photographic artist whose work deals with our relationship to landscape and notions of identity and belonging. He predominantly takes large format photographs with great technical precision, frequently from elevated positions. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES the PILGRIMS LMA/4632 Page 1 Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE LMA/463

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 THE PILGRIMS LMA/4632 Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE LMA/4632/A/01/001 Minute book 1917 May - Signed minutes, includes lists of candidates 1932 Jul awaiting election to the Pilgrims, Annual General Meetings and reports of the Executive Committee, statements of costs of dinners and treasurer's reports, Finance Committee meetings. 1 volume Former Reference: Ad/E1 LMA/4632/A/01/002 Minute book 1932 Jul - Signed minutes includes lists of candidates 1947 Jul awaiting election to the Pilgrims, Annual General Meetings and reports of the Executive Committee, statements of costs of dinners and treasurer's reports, Finance Committee meetings. 1 volume Former Reference: Ad/E2 LMA/4632/A/01/003 Minute book 1947 Jul - Signed minutes, includes lists of candidates 1954 May awaiting election to the Pilgrims, Annual General Meetings and reports of the Executive Committee, statements of costs of dinners and treasurer's reports, Finance Committee meetings. 1 file Former Reference: Ad/E3 LMA/4632/A/01/004 Minute book 1954 Jun - Signed minutes, includes lists of candidates 1975 Jun awaiting election to the Pilgrims, Annual General Meetings and reports of the Executive Committee, statements of costs of dinners and treasurer's reports, Finance Committee meetings. 1 volume Former Reference: Ad/E4 LMA/4632/A/01/005 Minutes 1984 Aug - 1 file 2009 Sep Former Reference: Ad/E6 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 THE PILGRIMS LMA/4632 Reference Description Dates LMA/4632/A/01/006 Minutes and agendas working copies 1935 May - Includes list of officers and executive committee 1949 Jul members 1949 - 1952. -

London Brochure.Pub

Tiffany Circle International Weekend Friday 28 February – Sunday 02 March 2014 London, United Kingdom Welcome It is with great joy that we welcome you to the UK to meet with the members of the UK Tiffany Circle, and to cement the bonds among the Circles from all over the world. We hope you have an enjoyable visit to the UK. As many of you are extending your visit to take in what London has to offer, we have put together this guide of our recommended activities. It contains a list of the most famous restaurants, where to go for afternoon tea, and some of the most popular and world renowned art galleries and museums. London is also home to the West End and many famous theatre venues, so these are included here with information about what shows will be on during your stay. We do hope this guide is useful and will whet your appetite for your upcoming visit. Welcome 2 West End shows 17 Schedule of events 3 West End shows map 18 Welcome to London 4 Restaurants 19 Travel to and from Heathrow 5 Restaurants map 20 Map of area around the Savoy 6 Bars 21 Travel within London 7 Bars map 22 Seeing London 8 Afternoon Tea 23 London Underground map 9 Afternoon Tea map 24 The Savoy 10 Attractions 25 Museums 11 Attractions map 26 Museums map 12 Shopping and spas 27 Art galleries 13 Shopping map 28 Art galleries map 14 Spas map 29 Theatres 15 Day trips 30 Theatres map 16 Day trips map 31 Links, contact and thank you 32 2 Schedule of Events Monday-Thursday, February 24-27: Guests begin to arrive in London and check in to the Savoy. -

London Sustainable Drainage Action Plan 2016

LONDON SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE ACTION PLAN 2016 LONDON SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE ACTION PLAN COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority December 2016 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN Photographs © Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk This document is supported by: LONDON SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE ACTION PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 PART 1: WHY WE NEED AND WANT MORE SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE 3 Surface water management in London 4 Surface water management challenges 5 What is sustainable drainage? 8 International experience of sustainable drainage 11 The case for sustainable drainage in London 12 Sustainable drainage vision 13 PART 2: THE SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE ACTION PLAN 19 The Sustainable Drainage Action Plan 20 Understanding the opportunities and benefits of sustainable drainage 21 Delivering sustainable drainage through new developments via the planning system 23 Retrofitting sustainable drainage across London 25 What can you do? Delivering sustainable drainage through domestic and local neighbourhood measures 56 Funding opportunities and regulatory incentives 59 Monitoring 61 Appendix 1: Action plan by year 62 Appendix 2: References 71 LONDON SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE ACTION PLAN 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY London is outgrowing its drains and sewers. The combined sewer system originally built over 150 years ago by Joseph Bazalgette has served us well, but it was designed for a smaller city with more green surfaces. The combined challenges of London’s growing population, changing land uses and changing climate mean that if we continue to rely on our current drains and sewers, we face an increasing risk of flooding.