General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Diameter and Depth of Lunar Craters - Course: HET 602, June 2002 Supervisor: Barry Adcock - Student: Eduardo Manuel Alvarez

Project: Diameter and Depth of Lunar Craters - Course: HET 602, June 2002 Supervisor: Barry Adcock - Student: Eduardo Manuel Alvarez Diameter and Depth of Lunar Craters Abstract The aim of this project is to find out the size and height of some features on the surface of the Moon from obtained observational field measures and the afterwards proper calculation in order to transform them into the corresponding physical final values. First of all it will be briefly described two different proceedings for the acquisition of the observational field measures and the theoretical development of the formulae that allow the conversion into the final required results. It will also be discussed the implicit theoretical errors that each method presents. Secondly, it will be described the actual applied measuring proceedings and the complete exposition of the field collected data, plus photos and sketches. Then it will be presented all the lunar related parameters corresponding to the same moments as when the measures were obtained, basically taken from the internet. After that, through the application of the proper formulae to each observational measure and the corresponding related parameters, it will be found out the required lunar features sizes and heights. Later the obtained final values will be compared to the actual values, analyzing the possible reasons of the differences, and suggesting improvements and special cares in the experimental application of the performed proceedings. Finally, an overall conclusion and the complete list of all the involved references will end this project report. 1) Theoretical considerations a) Measuring lunar surface sizes In order to measure the size of lunar features by telescopic observation from the Earth, it is necessary to firstly obtain some direct value related with its size and secondly apply the corresponding calculation that converts it into the desired actual length. -

Water on the Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity

Water on The Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity Arlin Crotts (Columbia University) For centuries some scientists have argued that there is activity on the Moon (or water, as recounted in Parts I & II), while others have thought the Moon is simply a dead, inactive world. [1] The question comes in several forms: is there a detectable atmosphere? Does the surface of the Moon change? What causes interior seismic activity? From a more modern viewpoint, we now know that as much carbon monoxide as water was excavated during the LCROSS impact, as detailed in Part I, and a comparable amount of other volatiles were found. At one time the Moon outgassed prodigious amounts of water and hydrogen in volcanic fire fountains, but released similar amounts of volatile sulfur (or SO2), and presumably large amounts of carbon dioxide or monoxide, if theory is to be believed. So water on the Moon is associated with other gases. Astronomers have agreed for centuries that there is no firm evidence for “weather” on the Moon visible from Earth, and little evidence of thick atmosphere. [2] How would one detect the Moon’s atmosphere from Earth? An obvious means is atmospheric refraction. As you watch the Sun set, its image is displaced by Earth’s atmospheric refraction at the horizon from the position it would have if there were no atmosphere, by roughly 0.6 degree (a bit more than the Sun’s angular diameter). On the Moon, any atmosphere would cause an analogous effect for a star passing behind the Moon during an occultation (multiplied by two since the light travels both into and out of the lunar atmosphere). -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

ANIC IMPACTS: MS and IRONMENTAL P ONS Abstracts Edited by Rainer Gersonde and Alexander Deutsch

ANIC IMPACTS: MS AND IRONMENTAL P ONS APRIL 15 - APRIL 17, 1999 Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research Bremerhaven, Germany Abstracts Edited by Rainer Gersonde and Alexander Deutsch Ber. Polarforsch. 343 (1999) ISSN 01 76 - 5027 Preface .......3 Acknowledgements .......6 Program ....... 7 Abstracts P. Agrinier, A. Deutsch, U. Schäre and I. Martinez: On the kinetics of reaction of CO, with hot Ca0 during impact events: An experimental study. .11 L. Ainsaar and M. Semidor: Long-term effect of the Kärdl impact crater (Hiiumaa, Estonia) On the middle Ordovician carbonate sedimentation. ......13 N. Artemieva and V.Shuvalov: Shock zones on the ocean floor - Numerical simulations. ......16 H. Bahlburg and P. Claeys: Tsunami deposit or not: The problem of interpreting the siliciclastic K/T sections in northeastern Mexico. ......19 R. Coccioni, D. Basso, H. Brinkhuis, S. Galeotti, S. Gardin, S. Monechi, E. Morettini, M. Renard, S. Spezzaferri, and M. van der Hoeven: Environmental perturbation following a late Eocene impact event: Evidence from the Massignano Section, Italy. ......21 I von Dalwigk and J. Ormö Formation of resurge gullies at impacts at sea: the Lockne crater, Sweden. ......24 J. Ebbing, P. Janle, J, Koulouris and B. Milkereit: Palaeotopography of the Chicxulub impact crater and implications for oceanic craters. .25 V. Feldman and S.Kotelnikov: The methods of shock pressure estimation in impacted rocks. ......28 J.-A. Flores, F. J. Sierro and R. Gersonde: Calcareous plankton stratigraphies from the "Eltanin" asteroid impact area: Strategies for geological and paleoceanographic reconstruction. ......29 M.V.Gerasimov, Y. P. Dikov, 0 . I. Yakovlev and F.Wlotzka: Experimental investigation of the role of water in the impact vaporization chemistry. -

Lunar Impact Basins Revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior

Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, Sean Solomon, David Smith, Frank Lemoine, Erwan Mazarico, Terence Sabaka, et al. To cite this version: Gregory Neumann, Maria Zuber, Mark Wieczorek, James Head, David Baker, et al.. Lunar im- pact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements. Science Advances , American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2015, 1 (9), pp.e1500852. 10.1126/sci- adv.1500852. hal-02458613 HAL Id: hal-02458613 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458613 Submitted on 26 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE PLANETARY SCIENCE 2015 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements 10.1126/sciadv.1500852 Gregory A. Neumann,1* Maria T. Zuber,2 Mark A. Wieczorek,3 James W. Head,4 David M. H. Baker,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 David E. Smith,2 Frank G. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics tive motion determines the type of boundary; convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative move- ment of the plates typically varies from zero to 100 mm annually.[2] Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This predic- The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century. tion of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some sup- porters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or grad- ual expansion of the globe.[3] Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth’s lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topog- raphy and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by the rotation of the globe and the tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative im- portance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate. -

GRAIL Gravity Observations of the Transition from Complex Crater to Peak-Ring Basin on the Moon: Implications for Crustal Structure and Impact Basin Formation

Icarus 292 (2017) 54–73 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus GRAIL gravity observations of the transition from complex crater to peak-ring basin on the Moon: Implications for crustal structure and impact basin formation ∗ David M.H. Baker a,b, , James W. Head a, Roger J. Phillips c, Gregory A. Neumann b, Carver J. Bierson d, David E. Smith e, Maria T. Zuber e a Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912, USA b NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA c Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA d Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA e Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: High-resolution gravity data from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission provide Received 14 September 2016 the opportunity to analyze the detailed gravity and crustal structure of impact features in the morpho- Revised 1 March 2017 logical transition from complex craters to peak-ring basins on the Moon. We calculate average radial Accepted 21 March 2017 profiles of free-air anomalies and Bouguer anomalies for peak-ring basins, protobasins, and the largest Available online 22 March 2017 complex craters. Complex craters and protobasins have free-air anomalies that are positively correlated with surface topography, unlike the prominent lunar mascons (positive free-air anomalies in areas of low elevation) associated with large basins. -

Four Hundred Years of Hits and Misses in Scientific Impact Crater Research

NIR Workshop, Gardnos − Gol, June 9th 2009 Four Hundred Years of Hits and Misses in Scientific Impact Crater Research Teemu Öhman Division of Geology, Department of Geosciences and Division of Astronomy, Department of Physical Sciences University of Oulu Finland Galileo Galilei Galileo Galilei (1564−1642) • First observer of lunar craters, late November 1609, Padua, Italy • Surface previously supposed smooth can be divided to dark lowlands (“large spots”) and bright highlands, which are covered with pits that have uplifted rims • A clear description of a central uplift Galilaei, D=15.5 km (LO) Johannes Kepler (1571−1630) • Supposed, like e.g. Plutarch in 1st century A.D., that the lunar lowlands are filled with water • Coined the terms “mare” and “terra” • Believed meteor(ite)s to have a cosmic origin(?) Kepler, D=32 km (LO) Robert Hooke (1635−1703) • Crater observer: Hipparchus, D=150 km Halley Micrographia, 1665 Lunar Orbiter Robert Hooke • First crater experimentalist: 1. Dropping bullets to a mixture of tobacco pipe clay and water: Æcraters “not unlike these of the Moon; but considering the state and condition of the Moon, there seems not any probability to imagine, that it should proceed from any cause analogus to this; for it would be difficult to imagine whence those bodies should come; and next, how the substance of the Moon should be so soft;” Robert Hooke 2. A pot of boiling alabaster: • When the boiling ceased, the surface was covered with craters • Compared these to terrestrial volcanoes Æ “…these pits in the Moon seem to -

About the Moon

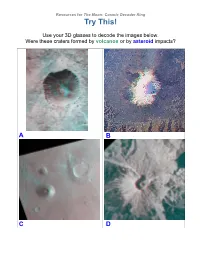

Resources for The Moon: Cosmic Decoder Ring Try This! Use your 3D glasses to decode the images below. Were these craters formed by volcanos or by asteroid impacts? A B C D Resources for The Moon: Cosmic Decoder Ring E F It can be difficult to tell them apart. Both volcanos and impact craters may have a high region in the center (a volcanic dome or an impact peak), and their rims can be higher than the surrounding area. One important difference is that the floor of an impact crater is lower than the ground surrounding the crater, while the bottom of a volcanic crater is still higher than the terrain. Answers: The asteroid impact craters are pictures A, E, and F; volcanic craters are shown in B, C, and D. Resources for The Moon: Cosmic Decoder Ring Websites for Further Exploration Connect to the Moon http://www.lpi.usra.edu/education/lprp/ This site includes paths for inquisitive adults, students, and formal and informal educators to find online resources, information, and opportunities for involvement in lunar science and exploration. Moon Zoo http://www.moonzoo.org/ Ways to Moon Zoo uses about 70,000 high resolution images gathered by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Citizen scientists are invited to categorize craters, boulders and more, including lava Get Involved channels and even all sorts of different spacecraft sitting on the Moon's surface. Lunar Science for Kids: Why is the Moon covered with craters? http://lunarscience.nasa.gov/kids/moon_craters This site, geared toward children ages 10 and up, features answers to a variety of questions about the Moon. -

Significance of Specific Force Models in Two Applications: Solar Sails to Sun-Earth L4/L5 and GRAIL Data Analysis Suggesting Lava Tubes and Buried Craters on the Moon

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations January 2016 Significance of Specific orF ce Models in Two Applications: Solar Sails to Sun-Earth L4/L5 and GRAIL aD ta Analysis Suggesting Lava Tubes and Buried Craters on the Moon Rohan Sood Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Sood, Rohan, "Significance of Specific orF ce Models in Two Applications: Solar Sails to Sun-Earth L4/L5 and GRAIL Data Analysis Suggesting Lava Tubes and Buried Craters on the Moon" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 1374. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1374 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 3414814237 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Rohan Sood Entitled Significance of Specific Force Models in Two Applications: Solar Sails to Sun-Earth L4/L5 and GRAIL Data Analysis Suggesting Lava Tubes and Buried Craters on the Moon For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Is approved by the final examining committee: Kathleen C. Howell Chair Henry J. Melosh James M. Longuski Dengfeng Sun To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Kathleen C. -

Morphology and Origin of Lunar Craters Von R

Morphology and origin of lunar craters Von R. S. Saunders, E. L. Haines, and J. E. Conel, Pasaderia" Summary: The general concensus among lunar geologists is th.at the majority of lunar craters, up to a few km in diameter, are of Impact origm. This conclusion is based on morphologie comparison with terrestrial meteorite craters, consideration of lunar regolrth formation by impact, direct observation of the morphology of smalI and microscopic craters on the lunar surface and experimental impact studtcs. Most Iarge craters are also interpreted to be ()f Impact origin. Although the morphology of unmodified craters changes somewhat with increasing size, these changes are completely gradational and there is no evidence to suggest that the predominant process of crater formation is different for large craters. However, selected craters of various sizes have been interpreted as volcanic. Understanding the origm of the multi-ring b asms presents greater difficulties. Theoretical treatments such as those of Bjork (1961) and Van Dorn (1969) seem to be the only approach. In such treatments it is nccessary to iriclude, in addition to hydrodynamic flow, large plastrc deformation arid br.it.tle failure of the target material, processes that are known to accompany Impact phenomena. Thus complete equations of state are required as well as a detailed microscopic (perhaps statistical) description of imperfections in rock mechanical properties. The required physical parameters arid the calculations are clearly formidable. Analysis of tracking data from Orbiter V has revealed positive graviational anomalies (mascons) over the circular maria (Mulle r und Sjogren, 1968). While a number of theories for the origin of the mascons has been proposed (see Kaula, 1969 for a summary), the nature of the anomalous masses remains in doubt as does the mechamsm whereby excess mass has been added to specific rcgtons, Resolution of these questions will tell us much about the thermal and struc tural history of the Moon.