Legislation and the Built Environment in the Arab-Muslim City Center For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses An archaeological study of the Yemeni highland pilgrim route between San'A' and Mecca. Al-Thenayian, Mohammed Bin A. Rashed How to cite: Al-Thenayian, Mohammed Bin A. Rashed (1993) An archaeological study of the Yemeni highland pilgrim route between San'A' and Mecca., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1618/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 0-+.LiLl-IL IgiiitAA9 ABSTRACT Mohammed A. Rashed al-Thenayian. Ph.D. thesis, University of Durham, 1993. An Archaeological Study of the Yemeni Highland Pilgrim Route between San'a' and Mecca This thesis centres on the study of the ancient Yemeni highland pilgrim route which connects $anT in the Yemen Arab Republic with Mecca in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The two composite sections of this route, which are currently situated in the Yemen and Saudi Arabia respectively, are examined thoroughly in this work. -

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC)

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC) Volume 7, Issue 1, Spring 2017 ISSN: 2075-0943, eISSN: 2520-0313 Journal DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc Issue DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.71 Homepage: https://www.umt.edu.pk/jitc/home.aspx Journal QR Code: Article: Conceptual Framework of an Ideal Muslim Indexing Partners Capital: Comparison between Early Muslim Capital of Baghdad and Islamabad Author(s): Faiqa Khilat Fariha Tariq Online Pub: Spring 2017 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.71.05 Article QR Code: Khilat, Faiqa, and Fariha Tariq. “Conceptual framework To cite this of an ideal Muslim capital: Comparison between article: early Muslim capital of Baghdad and Islamabad.” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 7, no. 1 (2017): 71–88. Crossref This article is open access and is distributed under the terms of Copyright Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 4.0 International Information License A publication of the Department of Islamic Thought and Civilization School of Social Science and Humanities University of Management and Technology Lahore Conceptual Framework of an Ideal Muslim Capital: Comparison between Early Muslim Capital of Baghdad and Islamabad Faiqa Khilat School of Architecture and Planning, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Fariha Tariq School of Architecture and Planning, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract According to Islamic teaching the Muslim capital city should incorporate fundamental elements of socio- economic enrichment and also a hospitable glance for its visitors. Various cities in the history of Islamic world performed as administrative capitals such as Medina, Damascus, Kufa, Baghdad, Isfahan, Mash’had etc. -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Muslim Women's Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond

Muslim Women’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond This book investigates female Muslims pilgrimage practices and how these relate to women’s mobility, social relations, identities, and the power struc- tures that shape women’s lives. Bringing together scholars from different disciplines and regional expertise, it offers in-depth investigation of the gendered dimensions of Muslim pilgrimage and the life-worlds of female pilgrims. With a variety of case studies, the contributors explore the expe- riences of female pilgrims to Mecca and other pilgrimage sites, and how these are embedded in historical and current contexts of globalisation and transnational mobility. This volume will be relevant to a broad audience of researchers across pilgrimage, gender, religious, and Islamic studies. Marjo Buitelaar is an anthropologist and Professor of Contemporary Islam at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. She is programme-leader of the research project ‘Modern Articulations of Pilgrimage to Mecca’, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Manja Stephan-Emmrich is Professor of Transregional Central Asian Stud- ies, with a special focus on Islam and migration, at the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany, and a socio-cultural anthropologist. She is a Principal Investigator at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies (BGSMCS) and co-leader of the research project ‘Women’s Pathways to Professionalization in Mus- lim Asia. Reconfiguring religious knowledge, gender, and connectivity’, which is part of the Shaping Asia network initiative (2020–2023, funded by the German Research Foundation, DFG). Viola Thimm is Professorial Candidate (Habilitandin) at the Institute of Anthropology, University of Heidelberg, Germany. -

The Cairo Street at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Nabila Oulebsir et Mercedes Volait (dir.) L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4915 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2009 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902820 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference ORMOS, István. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 In: L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2009 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ inha/4915>. ISBN: 9782917902820. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4915. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 1 The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos AUTHOR'S NOTE This paper is part of a bigger project supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA T048863). World’s fairs 1 World’s fairs made their appearance in the middle of the 19th century as the result of a development based on a tradition of medieval church fairs, displays of industrial and craft produce, and exhibitions of arts and peoples that had been popular in Britain and France. Some of these early fairs were aimed primarily at the promotion of crafts and industry. Others wanted to edify and entertain: replicas of city quarters or buildings characteristic of a city were erected thereby creating a new branch of the building industry which became known as coulisse-architecture. -

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

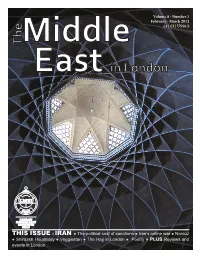

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility. -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

From Exclusivism to Accommodation: Doctrinal and Legal Evolution of Wahhabism

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 79 MAY 2004 NUMBER 2 COMMENTARY FROM EXCLUSIVISM TO ACCOMMODATION: DOCTRINAL AND LEGAL EVOLUTION OF WAHHABISM ABDULAZIZ H. AL-FAHAD*t INTRODUCTION On August 2, 1990, Iraq attacked Kuwait. For several days there- after, the Saudi Arabian media was not allowed to report the invasion and occupation of Kuwait. When the Saudi government was satisfied with the U.S. commitment to defend the country, it lifted the gag on the Saudi press as American and other soldiers poured into Saudi Arabia. In retrospect, it seems obvious that the Saudis, aware of their vulnerabilities and fearful of provoking the Iraqis, were reluctant to take any public position on the invasion until it was ascertained * Copyright © 2004 by Abdulaziz H. AI-Fahad. B.A., 1979, Michigan State University; M.A., 1980, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies; J.D., 1984, Yale Law School. Mr. Al-Fahad is a practicing attorney in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Conference on Transnational Connec- tions: The Arab Gulf and Beyond, at St. John's College, Oxford University, September 2002, and at the Yale Middle East Legal Studies Seminar in Granada, Spain, January 10-13, 2003. t Editors' note: Many of the sources cited herein are available only in Arabic, and many of those are unavailable in the English-speaking world; we therefore have not been able to verify them in accordance with our normal cite-checking procedures. Because we believe that this Article represents a unique and valuable contribution to Western legal scholarship, we instead have relied on the author to provide translations or to verify the substance of particular sources where possible and appropriate. -

Sinan and the Competitive Discourse of Earlymodern Islamic Architecture

GULRU NECIPOGLU CHALLENGING THE PAST: SINAN AND THE COMPETITIVE DISCOURSE OF EARLYMODERN ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE Oleg Grabar compared architecture in the formative pe As Spiro Kostof noted, "The very first monument of the riod of Islam, with its novel synthesis of Byzantine and new faith, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, was a pat Sasanian elements, to "a sort ofgraft on other living enti ently competitive enterprise" that constituted a conspic ties." "The Muslim world," he wrote, "did not inherit uous violation of the Prophet's strictures against costly exhausted traditions, but dynamic ones, in which fresh buildings. The Dome of the Rock and other Umayyad interpretations and new experiments coexisted with old imperial projects not only challenged the modest archi ways and ancient styles."I In this study dedicated to him I tecture of the early caliphs stationed in Medina, but at would like to show that a similar process continued to the same time invited a contest with the Byzantine archi inform the dynamics oflater Islamic architecture whose tectural heritage of Syria, the center of Umayyad power. history in the early-modern era was far from being a rep A well-known passage by the tenrh-century author etition of preestablished patterns constituting a mono Muqaddasi identifies the competition with Byzantine lithic tradition with fixed horizons. The "formation" of architecture, a living tradition associated with the great Islamic architecture(s) was a process that never stopped. est rival of the Umayyads, as the central motive behind Its parameters were continually redefined according to the ambitious building programs ofcAbd ai-Malik (685 the shifting power centers and emergent identities of 705) and al Walid 1(705-15):3 successive dynasties who formulated distinctive architec tural idioms accompanied by recognizable decorative The Caliph al-Walid beheld Syria to be a country that had modes. -

Dictionary of Islamic Architecture

DICTIONARY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE DICTIONARY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE Andrew Petersen London and New York First published 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1999 © 1996 Andrew Petersen All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-415-06084-2 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-21332-0 (pbk) ISBN 0-203-20387-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-20390-9 (Glassbook Format) Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix Entries 1 Appendix The Mediterranean World showing principal historic cities and sites 320 The Middle East and Central Asia showing principal historic cities and sites 321 Dedication This book is dedicated to my friend Jamie Cameron (1962–95) historian of James V of Scotland. Preface In one of the quarters of the city is the Muhammadan town, where the Muslims have their cathedral, mosque, hospice and bazar. They have also a qadi and a shaykh, for in every one of the cities of China there must always be a shaykh al- Islam, to whom all matters concerning Muslims are referred. -

Mamluk Studies Review Vol. V (2001)

MAMLU±K STUDIES REVIEW V 2001 MIDDLE EAST DOCUMENTATION CENTER (MEDOC) THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PLEASE NOTE: As of 2015, to ensure open access to scholarship, we have updated and clarified our copyright policies. This page has been added to all back issues to explain the changes. See http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/open-acess.html for more information. MAMLŪK STUDIES REVIEW published by the middle east documentation center (medoc) the university of chicago E-ISSN 1947-2404 (ISSN for printed volumes: 1086-170X) Mamlūk Studies Review is an annual, Open Access, refereed journal devoted to the study of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and Syria (648–922/1250–1517). The goals ofMamlūk Studies Review are to take stock of scholarship devoted to the Mamluk era, nurture communication within the field, and promote further research by encouraging the critical discussion of all aspects of this important medieval Islamic polity. The journal includes both articles and reviews of recent books. Submissions of original work on any aspect of the field are welcome, although the editorial board will periodically issue volumes devoted to specific topics and themes.Mamlūk Studies Review also solicits edited texts and translations of shorter Arabic source materials (waqf deeds, letters,fatawa and the like), and encourages discussions of Mamluk era artifacts (pottery, coins, etc.) that place these resources in wider contexts. An article or book review in Mamlūk Studies Review makes its author a contributor to the scholarly literature and should add to a constructive dialogue. Questions regarding style should be resolved through reference to the MSR Editorial and Style Guide (http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/msr.html) and The Chicago Manual of Style. -

Mediated Qur'anic Recitation and the Contestation of Islam In

Contestation of Islam in Contemporary Egypt Mediated Qur’anic Recitation and the Overview Islam in Egypt today is contested across a broad media spectrum from recorded sermons, films, television and radio programmes to newspapers, pamphlets and books. Print, recorded and broadcast media facilitate an ongoing ideological © Copyrighted Material debate about Islam – its nature and its normative social role – featuring a wide variety of discursive positions. known as Chapter 3 rooted in Islamic tradition and deeply felt by its practitioners (Nelson Can public Public Qur’anic recitation is immensely moving for Muslims. And yet, might expect the answer to be ‘no’, because the Qur’an’s linguistic content is Michael Frishkopf fixed and its recitation highly regulated.tilawa Nevertheless, scope for variation and stylistic variety.tilawa In the past, such divergence resulted from localised chains of transmission, shaped by contrastive contexts and did not typically convey widely significant ideological positions. However,) within thisover debate? the past tilawa century the mass media has generally facilitated the formation is and one circulation of Islam’s ofmost essential and universal practices, deeply more broadly recognisable and influential participate in ideological struggles to define Islam? Certainly, new edition of her book, rise of a Saudi style since the first edition appeared in 1985. This is precisely the period I am attempting, in part, to document here. My sincere thanks to Kristina Nelson, for her What is the role of Qur’anic recitation (generally groundbreaking study and insightfulThis chapter comments extends on the an seminalearlier draft, work to of Wael Kristina ‘Abd Nelson. al-Fattah, In the postscript to the Usama Dinasuri, Iman Mersal and Dr Ali Abu Shadi, for their critical insights and feedback, to staff at al-Azhar University, and to numerous Egyptians (reciters and others) with whom I’ve conducted countless informal discussions.