History in the Making Kyle Barrowman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON NE VIT QUE DEUX FOIS. ( You Only Live Twice

ON NE VIT QUE DEUX FOIS. ( You Only Live Twice. ) 1967 Produit par : Albert R. Broccoli et Harry Saltzman Réalisé par : Lewis Gilbert Scénario de : Roald Dahl Musique de : John Barry Chanté par : Nancy Sinatra D'après l'œuvre de Ian Fleming. DISTRIBUTION Sean CONNERY James Bond 007 Donald PLEASENCE Ernst Stavro Blofeld Teru SHIMADA Osato Akiko WAKABAYASHI Aki Mie HAMA Kissy Susuki Karin DOR Helga Brandt Tetsuro TAMBA 'Tigre' Tanaka Charles GRAY Henderson Loïs MAXWELL Miss Moneypenny Bernard LEE «M» Desmond LLEWELYN «Q» Tourné au: - Japon, à Tokyo - Grande-Bretagne, aux studios Pinewood à Londres PRE-GENERIQUE La navette spatiale américaine, Jupiter 16, a mystérieusement disparue dans l'espace avec son équipage; elle semble avoir été avalée par un vaisseau plus grand, qui a atterri au Japon d'après les Services Secrets britanniques. Les Etats-Unis accusent l'Union Soviétique de ce détournement et menacent d'entrer en guerre si cela devait ce reproduire. Les britanniques proposent d'enquêter, mais il faut agir avant le prochain lancement... SYNOPSIS Les Services Secrets britanniques, voulant à tout prix empêcher une guerre nucléaire entre les 'Deux Grands', mettent leur meilleur agent sur cette affaire; car tout porte à croire qu'une puissance étrangère soit l'auteur de cette diabolique machination. James Bond est donc envoyé au Japon, où il prend contacte avec Henderson, mais ce dernier se fait tuer avant qu'il ne puisse révéler toutes ses informations à 007; Bond arrive cependant à remonter jusqu'au commanditaire du meurtre, le puissant industriel japonais, Osato. 'Tigre' Tanaka, le chef des Services Secrets japonais, et James Bond mettent en commun leurs informations, qui les amènent sur une île volcanique où d'étranges activités ont été signalées. -

Primed for 11 Th Cl

hUished .... eekly. Ent~red as 2nd class matter in post office at Los Angeles, Calll 01. 44 No.9 Los Angeles, California Published Every Friday-10c Friday, March 1, 1957 PRESIDENT'S CORNER: OREGO~'ANS Open letter to '57 ALBANY (CALIF.) "OTED HONORED FOR chapter presidents PRIMED FOR 11 TH \YARTIME SERVICE TO NISEI~ JACL Most of the new 1957 PORTLAND. - Three prominent by Nebi Sumida. chairman. as Chapter officers have C.L. KEG (LASSIC Oregenians were henored by the sisted by George Azumano, Martba Japanese American Cit i zen s Osaki, V.p.; Roy Maeda, treas.; now' bet>n elected. ALBANY.-A let of Nisei who de League last Sunday for their Alice Kida, rec. sec.; Flo Ana May I congratulate you little bowling .or cheose to engage "faith in Americans of Japanese zawa, cor. sec.; Mary Sasaki, in other sperts will find that New ancestry and (their) courage in hist.; Kimi Tambara. Dr. Tesh upon your election as a York is not the only state where .Jphelding the principles of demo Kuge, del.; T. Tomiyasu and T • local JACL Chapter pre· a city of this name exists. cracy". Yasueda, advisers. On the other hand. JACL bowl sident? This is one of the ers acress the country have been Natienal JACL scrolls .of appre Gresham-Troutdale elected Dr. most difficult and most planning since last year to make ciation were presented by Masae Joe Onchi, pres.; Frank Ande, 1st the Hth annual Natienal JACL 5etow: JACL director, of San V.p.; Geerge Onchi, 2nd v.p.; Negi responsible positions that Bowling Teurnament opening here Francisco te E. -

Introduction the Making of Decadence in Japan 1

Notes Introduction The Making of Decadence in Japan 1. Nakao Seigo, “Regendered Artistry: Tanizaki Junichiro and the Tradition of Decadence,” (Ph.D. Diss. New York U, 1992), p. 53. 2. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 122. 3. Ibid., p. 123. 4. Ibid., p. 130. 5. Kamishima Jirō, Kindai nihon no seishin kōzō [The Structure of the Modern Japanese Mind]. Tokyo: Iwanami, 1961, p. 183. Kamishima introduces the word “reiki” (encouraging reinforcement) to describe the acculturation pro- cess that appeared to further the social phenomenon of decadence in late Meiji Japan. He argues that individualism, the decay of conventional ethics, the corruption of public morals, and a collective neurosis, etc., were ubiqui- tous by the end of the Meiji period. According to Kamishima, these social fac- tors already existed in pre-Meiji Japan, but became more visible in the 1900s. These indigenous factors were not transplanted but simply “reinforced” through contact with the West. 6. In reality, Ariwara no Narihira lived in the ninth century (825–880). Ise Monogatari offers a fictional version of Narihira and places him in the context of the year 950 or thereabouts. Karaki traces Narihira’s decadent image not on the basis of biographical facts but via the fictional image created by the author of Ise Monogatari. See Karaki Junzō, Muyōsha no keifu. Tokyo: Chikuma, 1960, p. 10. 7. Fujiwara no Kusuko (?–810), a daughter of Fujiwara no Tanetsugu and the wife of Fujiwara no Tadanushi, was Emperor Heijō’s mistress. She and her brother, Fujiwara no Nakanari, vehemently opposed the Emperor’s decision to leave the throne. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

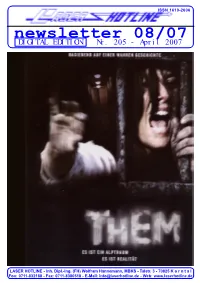

Newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 205 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 08/07 (Nr. 205) April 2007 editorial Gefühlvoll, aber nie kitschig: Susanne Biers Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, da wieder ganz schön viel zusammen- Familiendrama über Lügen und Geheimnisse, liebe Filmfreunde! gekommen. An Nachschub für Ihr schmerzhafte Enthüllungen und tiefgreifenden Kaum ist Ostern vorbei, überraschen Entscheidungen ist ein Meisterwerk an Heimkino fehlt es also ganz bestimmt Inszenierung und Darstellung. wir Sie mit einer weiteren Ausgabe nicht. Unsere ganz persönlichen Favo- unseres Newsletters. Eigentlich woll- riten bei den deutschen Veröffentli- Schon lange hat sich der dänische Film von ten wir unseren Bradford-Bericht in chungen: THEM (offensichtlich jetzt Übervater Lars von Trier und „Dogma“ genau dieser Ausgabe präsentieren, emanzipiert, seine Nachfolger probieren andere doch im korrekten 1:2.35-Bildformat) Wege, ohne das Gelernte über Bord zu werfen. doch das Bilderbuchwetter zu Ostern und BUBBA HO-TEP. Zwei Titel, die Geblieben ist vor allem die Stärke des hat uns einen Strich durch die Rech- in keiner Sammlung fehlen sollten und Geschichtenerzählens, der Blick hinter die nung gemacht. Und wir haben es ge- bestimmt ein interessantes Double- Fassade, die Lust an der Brüchigkeit von nossen! Gerne haben wir die Tastatur Beziehungen. Denn nichts scheint den Dänen Feature für Ihren nächsten Heimkino- verdächtiger als Harmonie und Glück oder eine gegen Rucksack und Wanderschuhe abend abgeben würden. -

Page 1 of 12 Moma | Press | Releases | 2000 | Exhibition Features

MoMA | press | Releases | 2000 | Exhibition Features Films from a Diversity of Genres ab... Page 1 of 12 EXHIBITION FEATURES FILMS FROM A DIVERSITY OF GENRES ABOUT WARS THAT NEVER TOOK PLACE For Immediate Release September 2000 The Imaginary War September 14–October 15, 2000 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters 1 and 2 The Imaginary War is an international selection of films about fictional wars that served as warnings or critiques of real wars. The exhibition includes a range of films, from Aelita (1924), Yakov Protazanov’s fantasy of a proletarian uprising on Mars, and the Marx Brothers’s anti- totalitarian burlesque Duck Soup (1933), to Stanley Kubrick’s atomic satire Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Barry Levinson’s prescient Wag the Dog (1997). The Imaginary War, part of The Museum of Modern Art’s Open Ends exhibition, is on view from September 14 to October 15, 2000. The program was organized by Joshua Siegel, Assistant Curator, Department of Film and Video. The Imaginary War was inspired by a comment Jean-Luc Godard made about his 1963 film Les Carabiniers, an anti-war allegory that shatters all conventions of the genre by blending documentary actuality and fanciful invention: “In dealing with war, I followed a very simple rule. I assumed I had to explain to children not only what war is, but what all wars have been …rather as if I were illustrating the many—yet always drearily familiar—faces of war by projecting imagerie sheets through a magic lantern, in the manner of the early cameramen who used to fabricate newsreels.” The Imaginary War features a diversity of genres—science fiction and fantasy, slapstick comedy and the political thriller, pseudo-documentary and experimental and animation works. -

Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature ETHNIC MINORITIES IN THE AMERICAN FILM INDUSTRY Diploma Thesis Brno 2006 Supervisor: Written by: Michael George, M.A. Lucie Pezlarová - 1 - Pod ěkování Děkuji všem u čitel ům Katedry Anglického jazyka a Literatury na Pedagogické fakult ě, kte ří ovlivnili mé názory na výuku cizích jazyk ů svými p řednáškami a seminá ři. Zvlášt ě bych cht ěla pod ěkovat vedoucímu mé diplomové práce Michealu Georgovi, M.A. za cenné rady a konstruktivní p řipomínky, které p řisp ěly ke kone čné podob ě této práce. Acknowledgements I would like hereby to take this opportunity to thank all the teachers of the Department of English Language and Literature at the Faculty of Education who have influenced opinions by their lectures and seminars about foreign language. My grateful thanks belong to the supervisor of my diploma thesis Michael George, M.A. for his valuable advice and constructive comments which contributed to the final form of this work. - 2 - Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci zpracovala samostatn ě a použila jen prameny uvedené v seznamu literatury. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykov ě univerzit ě v Brn ě v knihovn ě Pedagogické fakulty a zp řístupn ěna ke studijním ú čel ům. I proclaim that my diploma thesis is a piece of individual writing and that only the sources cited in the Bibliography list were used to compile it. I agree with this diploma thesis being deposited in the Library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with its being made available for academic purposes. -

Full Book PDF Download

TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page i The naval war film TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page ii TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iii The naval war film GENRE, HISTORY, NATIONAL CINEMA Jonathan Rayner Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page iv Copyright © Jonathan Rayner 2007 The right of Jonathan Rayner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7098 8 hardback EAN 978 0 7190 7098 3 First published 2007 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in 10.5/12.5pt Sabon by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath TNWA01 16/11/06 11:23 AM Page v For Sarah, who after fourteen years knows a pagoda mast when she sees one, and for Jake and Sam, who have Hearts of Oak but haven’t got to grips with Spanish Ladies. -

El Brand Placement Elemento Configurador De La Metamarca

UNIVERSIDAD DE VIGO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y DE LA COMUNICACIÓN Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y Comunicación Programa de Doctorado en Comunicación Tesis doctoral El brand placement, elemento configurador de la metamarca James Bond Presentada por: Vicente Badenes Plá Directora: Dra. Aurora García González Pontevedra - 2015 RESUMEN DE LA TESIS DOCTORAL La tesis pretende demostrar la capacidad configuradora de la técnica del brand placement en la marca James Bond, de modo que ésta deviene en metamarca, esto es, en una marca para las marcas. A través de un completo análisis de contenido de las 23 películas oficiales que conforman la marca-franquicia James Bond, se reseñan cerca de un millar de marcas integradas en sus películas a lo largo de 50 años, indicando el minuto en que aparecen y utilizando 5 categorías para la investigación, que son: Automóviles, Localizaciones, Bebidas, Moda y Complementos, Gadgets & TIC a las que se suma una sexta categoría por exclusión denominada Otros. El objeto de estudio de la tesis son las 23 películas y comprende un marco temporal de medio siglo, los 50 años comprendidos entre 1962, fecha de la primera entrega Agente 007 contra el Dr. No, y 2012, fecha de la 23ª y hasta la fecha última entrega Skyfall. Para alcanzar ese objetivo se ha recurrido al análisis de contenido y se ha utilizado el universo completo. Para localizar las marcas integradas se ha realizado un análisis cuantitativo, con indicación del número de marcas y de su distribución porcentual por categorías y un análisis cualitativo, con la revisión de los casos más destacados en cada entrega, lo que da lugar a un total de más de 60 casos. -

Hans J. Salter Papers PASC-M.0137

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft1v19n4t9 No online items Finding Aid for the Hans J. Salter Papers PASC-M.0137 Finding aid prepared by Rachel Curtis, 2009. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 March 12. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Hans J. Salter PASC-M.0137 1 Papers PASC-M.0137 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Hans J. Salter papers Creator: Salter, Hans J. Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0137 Physical Description: 90 Linear Feet(180 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1935-1982 Abstract: The collection consists of music, personal papers, correspondence, photographs, production materials, business papers and periodical clippings of one of Universal Pictures' film composers, Hans J. Salter. The various kinds of music are manuscript and published music including conductor's scores, orchestral parts, sheet music, published music books, and sound recordings on 7", 10", and 12" sound discs, 7" and 10" open reel analog tapes, and sound cassettes. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIO MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audio materials. For information about the access status of the material that you are looking for, refer to the Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements note at the series and file levels. -

List of Titles 1. ABRAHAM LINCOLN (1930, BW, 92 MIN)

© 2003 Trocadero Film Library -selected masters- Vidmast #5542810 List of titles 1. ABRAHAM LINCOLN (1930, BW, 92 MIN) Walter Huston, Una Merkel, Russell Simpson, Jason Robards, Sr., directed by D. W. Griffith. Huston portrays Lincoln from his early days as a country lawyer, his courting of Mary Todd through his quest for the presidency, the civil war and the assassination. Some great war scenes. 2. ABILENE TOWN (1946, BW, 89 MIN) Randolph Scott, Ann Dvorak, Edgar Buchanan, Rhonda Fleming, Lloyd Bridges, directed by Edwin L. Marin. In the years following the Civil War, the town of Abilene, Kansas is poised on the brink of an explosive confrontation. A line has been drawn down the center of the town where the homesteaders and the cattlemen have come to a very uneasy truce. The delicate peace is inadvertently shattered when a group of new homesteaders lay down their stakes on the cattlemen's side of town, upsetting the delicate balance that had existed thus far and sparking an all-out war between the farmers, who want the land tamed and property lines drawn, and the cowboys, who want the prairies to be open for their cattle to roam. 3. ADMIRAL WAS A LADY, THE (1950, BW, 90 MIN) Edmond O'Brien, Wanda Hendrix, Rudy Vallee, directed by Albert S. Rogell. Four war veterans with a passion for avoiding work compete for the attentions of an ex-wave. © 2003 Trocadero Film Library -selected masters- Vidmast #5542810 4. ADVENTURERS, THE (1950, BW, 82 MIN) Dennis Price, Siobhan McKenna. Four people, none of who trusts the other, set out to discover a cash of diamonds hidden in the African jungle. -

The Transnational Modern Dance of Itō Michio a DISSERTATION

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Altered Belonging: The Transnational Modern Dance of Itō Michio A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Theatre and Drama By Tara Rodman EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2017 2 © Copyright by Tara Rodman 2017 All Rights Reserved 3 Abstract This dissertation, “Altered Belonging: The Transnational Modern Dance of Itō Michio,” argues that Itō forged an artistic and social identity out of the very categories of racial and national difference typically used to exclude Japanese from Euro-American society. The strategies he employed provide a paradigm for how performing bodies marked as foreign claim freedom of mobility and a sense of belonging in their adopted communities. Addressing the full span of his career across five decades of performance in Europe, the U.S., and Japan, this dissertation restores the historic and analytic relationships among geographically distinct archives. By uncovering the linkages between his eurythmics training in Hellerau, Germany, his modernist collaborations in London, his nearly three decades dancing in New York and Los Angeles, and his Pan-Asianist activities under Japan’s wartime empire, I recover, for instance, how Itō’s experience of New York stage Orientalism later shadows his Pan-Asianist planned performances for Imperial Japan, and how the universalist ideals of his Hellerau training resurfaced as an ideology of community dance in Los Angeles. The trans-oceanic linkages thus rendered legible are relevant for understanding not only Itō’s career but also the integrated nature of twentieth-century modernism and the strategies by which modern artists refashioned alterity into a basis for creative freedom and freedom of movement.