The Transnational Modern Dance of Itō Michio a DISSERTATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

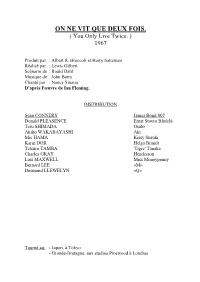

ON NE VIT QUE DEUX FOIS. ( You Only Live Twice

ON NE VIT QUE DEUX FOIS. ( You Only Live Twice. ) 1967 Produit par : Albert R. Broccoli et Harry Saltzman Réalisé par : Lewis Gilbert Scénario de : Roald Dahl Musique de : John Barry Chanté par : Nancy Sinatra D'après l'œuvre de Ian Fleming. DISTRIBUTION Sean CONNERY James Bond 007 Donald PLEASENCE Ernst Stavro Blofeld Teru SHIMADA Osato Akiko WAKABAYASHI Aki Mie HAMA Kissy Susuki Karin DOR Helga Brandt Tetsuro TAMBA 'Tigre' Tanaka Charles GRAY Henderson Loïs MAXWELL Miss Moneypenny Bernard LEE «M» Desmond LLEWELYN «Q» Tourné au: - Japon, à Tokyo - Grande-Bretagne, aux studios Pinewood à Londres PRE-GENERIQUE La navette spatiale américaine, Jupiter 16, a mystérieusement disparue dans l'espace avec son équipage; elle semble avoir été avalée par un vaisseau plus grand, qui a atterri au Japon d'après les Services Secrets britanniques. Les Etats-Unis accusent l'Union Soviétique de ce détournement et menacent d'entrer en guerre si cela devait ce reproduire. Les britanniques proposent d'enquêter, mais il faut agir avant le prochain lancement... SYNOPSIS Les Services Secrets britanniques, voulant à tout prix empêcher une guerre nucléaire entre les 'Deux Grands', mettent leur meilleur agent sur cette affaire; car tout porte à croire qu'une puissance étrangère soit l'auteur de cette diabolique machination. James Bond est donc envoyé au Japon, où il prend contacte avec Henderson, mais ce dernier se fait tuer avant qu'il ne puisse révéler toutes ses informations à 007; Bond arrive cependant à remonter jusqu'au commanditaire du meurtre, le puissant industriel japonais, Osato. 'Tigre' Tanaka, le chef des Services Secrets japonais, et James Bond mettent en commun leurs informations, qui les amènent sur une île volcanique où d'étranges activités ont été signalées. -

TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Toshiko Akiyoshi 穐吉敏子 (December 12, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 29, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript 97 pp. Brown: Today is June 29th, 2008, and this is the oral history interview conducted with Toshiko Akiyoshi in her house on 38 W. 94th Street in Manhattan, New York. Good afternoon, Toshiko-san! Akiyoshi: Good afternoon! Brown: At long last, I‟m so honored to be able to conduct this oral history interview with you. It‟s been about ten years since we last saw each other—we had a chance to talk at the Monterey Jazz Festival—but this interview we want you to tell your life history, so we want to start at the very beginning, starting [with] as much information as you can tell us about your family. First, if you can give us your birth name, your complete birth name. Akiyoshi: To-shi-ko. Brown: Akiyoshi. Akiyoshi: Just the way you pronounced. Brown: Oh, okay [laughs]. So, Toshiko Akiyoshi. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Akiyoshi: Yes. Brown: And does “Toshiko” mean anything special in Japanese? Akiyoshi: Well, I think,…all names, as you know, Japanese names depends on the kanji [Chinese ideographs]. Different kanji means different [things], pronounce it the same way. And mine is “Toshiko,” [which means] something like “sensitive,” “susceptible,” something to do with a dark sort of nature. -

Primed for 11 Th Cl

hUished .... eekly. Ent~red as 2nd class matter in post office at Los Angeles, Calll 01. 44 No.9 Los Angeles, California Published Every Friday-10c Friday, March 1, 1957 PRESIDENT'S CORNER: OREGO~'ANS Open letter to '57 ALBANY (CALIF.) "OTED HONORED FOR chapter presidents PRIMED FOR 11 TH \YARTIME SERVICE TO NISEI~ JACL Most of the new 1957 PORTLAND. - Three prominent by Nebi Sumida. chairman. as Chapter officers have C.L. KEG (LASSIC Oregenians were henored by the sisted by George Azumano, Martba Japanese American Cit i zen s Osaki, V.p.; Roy Maeda, treas.; now' bet>n elected. ALBANY.-A let of Nisei who de League last Sunday for their Alice Kida, rec. sec.; Flo Ana May I congratulate you little bowling .or cheose to engage "faith in Americans of Japanese zawa, cor. sec.; Mary Sasaki, in other sperts will find that New ancestry and (their) courage in hist.; Kimi Tambara. Dr. Tesh upon your election as a York is not the only state where .Jphelding the principles of demo Kuge, del.; T. Tomiyasu and T • local JACL Chapter pre· a city of this name exists. cracy". Yasueda, advisers. On the other hand. JACL bowl sident? This is one of the ers acress the country have been Natienal JACL scrolls .of appre Gresham-Troutdale elected Dr. most difficult and most planning since last year to make ciation were presented by Masae Joe Onchi, pres.; Frank Ande, 1st the Hth annual Natienal JACL 5etow: JACL director, of San V.p.; Geerge Onchi, 2nd v.p.; Negi responsible positions that Bowling Teurnament opening here Francisco te E. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

Slovenian Dances and Their Sources in California

SLOVENIAN DANCES AND THEIR SOURCES IN CALIFORNIA ELSIE IVANCICH DUNIN Slovenian dance repertoire in California is traced in two Slovenski plesni repertoar v Kaliforniji živi v dveh social contexts: international recreational folk dancing družbenih kontekstih: ob mednarodnih rekreacijskih events and Slovene/American community events. Dancers ljudskih plesnih dogodkih in ob dogodkih slovensko-ameriške in California Folk Dance Federation clubs dance to skupnosti. V klubih kalifornijskega Združenja za ljudske recorded music, while Slovene/American events feature local plese plesalci plešejo ob posnetkih glasbe, medtem ko ob accordion-based bands. Recorded music in the clubs offers slovensko-ameriških dogodkih gostijo lokalne harmonikarske a non-changing soundscape for the dancers, who conform zasedbe. Posneta glasba v klubih ponuja plesalcem uniformly to a taught sequence of a dance that fits the nespremenljivo zvočno podobo: plesalci se poenotijo in recording in contrast to greater dancing variance at Slovene/ uskladijo z naučeno plesno sekvenco, ustrezno glasbenemu American dance events. posnetku, kar je v nasprotju z veliko plesno variantnostjo v Keywords: California; Folk Dance Federation; Slovene/ slovensko-ameriških plesnih dogodkih. Americans; accordion bands; polka Ključne besede: Kalifornija, Združenje za ljudske plese, Slovenci/Američani, harmonikarski orkestri, polka PRELUDE My earliest introduction to dances of Slovenia was by Mirko Ramovš during the Folklore Summer School (Ljetna škola folklora), held at the sport’s center on Badija island (near the island of Korčula), August 1969, and then again on Badija in 1971. I remember his care- ful and well-organized instructions with background information on the dances. I recall thinking that his fine teaching had to do with his knowledge of Kinetography Laban, which is an excellent tool to perceive and to analyze dancing movements, but also to describe movements to those of us who were not familiar with the dance forms. -

Subjugation IV

Subjugation 4 Tribulation by Fel (aka James Galloway) ToC 1 To: Title ToC 2 Chapter 1 Koira, 18 Toraa, 4401, Orthodox Calendar Wednesday, 28 January 2014, Terran Standard Calendar Koira, 18 Toraa, year 1327 of the 97th Generation, Karinne Historical Reference Calendar Foxwood East, Karsa, Karis Amber was starting to make a nuisance of herself. There was just something intrinsically, fundamentally wrong about an insufferably cute animal that was smart enough to know that it was insufferably cute, and therefore exploited that insufferable cuteness with almost ruthless impunity. In the 18 days since she’d arrived in their house, she’d quickly learned that she could do virtually anything and get away with it, because she was, quite literally, too cute to punish. Fortunately, thus far she had yet to attempt anything truly criminal, but that didn’t mean that she didn’t abuse her cuteness. One of the ways she was abusing it was just what she was doing now, licking his ear when he was trying to sleep. Her tiny little tongue was surprisingly hot, and it startled him awake. “Amber!” he grunted incoherently. “I’m trying to sleep!” She gave one of her little squeaking yips, not quite a bark but somewhat similar to it, and jumped up onto his shoulder. She didn’t even weigh three pounds, she was so small, but her little claws were like needles as they kneaded into his shoulder. He groaned in frustration and swatted lightly in her general direction, but the little bundle of fur was not impressed by his attempts to shoo her away. -

March 2019 Highlights

Vol. 62, Issue 3 March 2019 HIGHLIGHTS To create the Beloved Community by inspiring and empowering all souls to live bold and compassionate lives. The Interim Journey The Unknown Journey By Rev. Kathleen Rolenz By Rev. John T. Crestwell, Jr. At my first service with you in January In August 2018 I had a biopsy to see if I 2018, then President Ken Apfel presented had prostate cancer. I do. Stage 1. It was me with a walking stick – the same walk- caught early enough to give me several ing stick given to me by the Fox Valley UU treatment options. I feel fine. In June and Unitarian Universalist Church of Annapolis Fellowship in Appleton, WI. That service July I will be receiving proton beam thera- marked the beginning of my 30 month py in Baltimore for eight weeks, Monday journey with you, knowing that our time through Friday. That’s 40 trips back and had a beginning, a middle and an end in forth to B-more and I bet it will be tedious. June 2020. I have that walking stick in my office as a vis- However, I will be taking some days off during the treat- ual reminder of what it means to live and work and walk ments; I don’t expect to miss any major time at church. through this interim time. That could change though—I really don’t know at this point. The metaphor of journey runs deep throughout reli- I expect to have a full recovery but I know my life will gious and spiritual traditions because all journeys have change in this process. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

4-28-18 Jazz Ensemble

Williams Jazz Ensemble Kris Allen, director Program Long Yellow Road – Toshiko Akiyoshi I Ain’t Gonna Ask No More – Toshiko Akiyoshi Kogun – Toshiko Akiyoshi Mobile – Toshiko Akiyoshi Mount Harissa – Duke Ellington Haitian Fight Song – Charles Mingus, arr. Sy Johnson Leilani’s Mirror – Geoff Keezer Bad Dream – Earl Macdonald Williams Jazz Ensemble Jonah Levy ’18, alto and soprano saxophone Jimmy Miotto ’18, trumpet Richard Jin ’18, alto saxophone Daniel Fisher ’18, trumpet David Azzara ’19, tenor and alto saxophone Stuart Mack, trumpet Jeff Pullano ’19, tenor and soprano saxophone Jared Berger ’21, trumpet Kris Allen, director, baritone saxophone Vijay Kadiyala ’20, trumpet Ananth Shastri ’21, flute Will Doyle ’19, trombone and tuba Andrew Aramini ’19, piano Jared Bathen ’20, trombone Peter Duke ’21, piano Kiersten Campbell ’21, trombone Jeff Pearson ’20, guitar Andrew Rule ’21, trombone Rachel Porter ’20, bass Sammy Rososky ’19, trombone Josh Greenzeig ’20, drumset Nick Patino ’21, drumset Saturday, April 28, 2018 8:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Please turn off cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. See music.williams.edu for full details and additional happenings as well as to sign up for the weekly e- newsletters. Upcoming Events Kurt Pfrommer ’18, tenor Sun Apr 29 | Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall | 3:00 PM | free Calvin Ludwig ’18, flute Sun Apr 29 | Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall | 5:00 PM | free Violin Studio Recital Sun Apr 29 | Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall | 7:00 PM | free Sitar and Tabla Studio Recital -

Acknowledgement to Reviewers of International Journal of Molecular

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 1336-1374; doi:10.3390/ijms16011336 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Editorial Acknowledgement to Reviewers of the International Journal of Molecular Sciences in 2014 IJMS Editorial Office, MDPI AG, Klybeckstrasse 64, CH-4057 Basel, Switzerland Published: 7 January 2015 The editors of the International Journal of Molecular Sciences would like to express their sincere gratitude to the following reviewers for assessing manuscripts in 2014: Abass, Khaled Agterberg, Martijn J. H. Aleman, Tomas S. Abbott, David H. Aguilar, Claudio Alexander, David Earl Abdelmohsen, Kotb Aguilar-Reina, José Alexander, Stephanie Abdraboh, Mohamed Agulló-Ortuño, M. Teresa Alexiou, Christoph Abe, Naohito Agyei, Dominic Alexis, Frank Abe, Toshiaki Ahmed, Khalil Alexopoulos, A. Abou Neel, Ensanya A. Ahmed, Salahuddin Alfandari, Dominique Abou-Alfa, Ghassan Ahn, Joong-Hoon Alhede, Morten Abraini, Jacques H. Ahn, Suk-Kyun Alisi, Anna Abram, Florence Aibner, Thomas Alison, Malcolm R. Abusco, Anna Scotto Aizawa, Shin-Ichi Al-Kateb, Huda Abzalimov, Rinat Ajikumar, Parayil Kumaran Allen, Randy Ackland, K. Akashi, Makoto Aller, Patricio Acuna-Castroviejo, Darío Akbar, Sheikh Mohammad Fazle Almagro, Lorena Acunzo, M. Akbarzadeh, A. H. Almeida, Raquel Adamcakova-Dodd, Andrea Akeda, Koji Alonso-Nanclares, Lidia Adeniji, Adegoke Akimoto, Jun Alpini, Gianfranco Adessi, Alessandra Aktas, C. Alric, Jean Adhikary, Amitava Akue, Jean Paul Altenbach, Susan B. Afseth, Nils Al Ghouleh, Imad Altmann, André Agalliu, Dritan Al-Ahmadie, Hikmat A. Alvarez Ponces, David Agarwal, Anika Alber, Birgit E. Alvarez-Suarez, José M. Ageorges, Agnès Albero, Cenci Alves, Artur Agorastos, Agorastos Alcaro, Stefano Amacher, David E. Agostini, Marco Alemán, José Amado, Francisco Int. -

Dancers: New Work by Borbála Kováts Dance in California: 150 Years of Innovation

USF Home > Library Home > Thacher Gallery The University of San Francisco’s Thacher Gallery presents January 13—February 23, 2003 Hungarian collage artist Borbála Kováts explores dance through computer- generated textures and imagery alongside a San Francisco Performing Arts Library & Museum (SFPALM) photo history of California Dance. Please join us Thursday, February 20, from 3 to 5 p.m. for the Closing Reception featuring an improvisational dance performance by the USF Dance Program at 4 p.m. Co-sponsored by SFPALM, USF’s Visual and Performing Arts Department and Budapest, Hungary Cultural Immersion Program. Dancers: New Work by Borbála Kováts Dance in California: 150 Years of Innovation Dancers: New Work by Borbála Kováts Following studies in fine arts and experimentation with traditional graphic arts, I first turned to photocopying and then to digital techniques. In recent years, I have engaged in preparing computer prints and have found that digital techniques are suitable for more than transmitting and perfecting photographic images of everyday life. I now use the computer to search for a language of representation that is unique to the digital medium. In my work the role of technique is far wider ranging than transmitting or retouching images; with the aid of computerized tools, I create a new pictures within the machine itself. My compositions are mostly non-figurative and work to create an integrated pictorial unity using various digital graphic surfaces. Starting from digital photographs, scanned material, or my own drawings, I create new surfaces and shapes using the computer so that the original pictures lose their earlier meanings.