The Fulani Jihad & Its Implication for National Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Pt.II: Colonialism, Nationalism, the Harem 19th-20th centuries” Week 11: Nov. 27-9; Dec. 2 “Northern Nigeria: from Caliphate to Colony” Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Early 19th C. Jihad established Sokoto Caliphate: • Uthman dan Fodio • Born to scholarly family (c.1750) • Followed conservative Saharan brotherhood (Qadiriyya) Northern Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1790s – 1804: growing reputation as teacher • Preaching against Hausa Islam: state we left in discussion of Kano Palace18th c. (Nast) • ‘corruption’: illegal imposition various taxes • ‘paganism’: continued practice ‘pre-Islamic’ rituals (especially Bori spirit cult) • Charged political opponent, Emir of Gobir as openly supporting: first ‘target’ of jihad Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1804: beginning of jihad • Long documented correspondence/debate between them • Emir of Gobir did not accept that he was ‘bad Muslim’ who needed to ‘convert’ – dan Fodio ‘disagreed’ • Declared ‘Holy War’ Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Drew in surrounding regions: why attracted? • marginalization vis-à-vis central Hausa provinces • exploited by excessive taxation • attraction of dan Fodio’s charisma, genuine religious fervour Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1817, Uthman dan Fodio died: • Muhamed Bello (son) took over as ‘caliph’ • nature of jihad changed fundamentally: became one of ‘the heart and mind’ • ‘conquest’ only established fragile boundaries of state • did not create the Islamic regime envisaged by dan Fodio Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • New ‘Islamic state’ carved out of pre-existing Muslim society: needed full legitimization • Key ‘tool’ to shaping new society -- ‘educating people to understand the Revolution’ -- was education Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nana Asma’u (1793 – 1864): - educated daughter of Uthman dan Fodio - fluent in Arabic, Fulfulbe, Hausa, Tamechek [Tuareg] - sister Mohamed Bello Nigeria: 19th-20th C. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12Th AH/18Th CE Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah Al-Dihlawi

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Islamic economic thinking in the 12th AH/18th CE century with special reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75432/ MPRA Paper No. 75432, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:58 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Center King Abdulaziz University http://spc.kau.edu.sa FOREWORD The Islamic Economics Research Center has great pleasure in presenting th Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12th AH (corresponding 18 CE) Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi). The author, Professor Abdul Azim Islahi, is a well-known specialist in the history of Islamic economic thought. In this respect, we have already published his following works: Contributions of Muslim Scholars to th Economic Thought and Analysis up to the 15 Century; Muslim th Economic Thinking and Institutions in the 16 Century, and A Study on th Muslim Economic Thinking in the 17 Century. The present work and the previous series have filled, to an extent, the gap currently existing in the study of the history of Islamic economic thought. In this study, Dr. Islahi has explored the economic ideas of Shehu Uthman dan Fodio of West Africa, a region generally neglected by researchers. He has also investigated the economic ideas of Shaykh Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab, who is commonly known as a religious renovator. Perhaps it would be a revelation for many to know that his economic ideas too had a role in his reformative endeavours. -

Soil Survey Papers No. 5

Soil Survey Papers No. 5 ANCIENTDUNE FIELDS AND FLUVIATILE DEPOSITS IN THE RIMA-SOKOTO RIVER BASIN (N.W. NIGERIA) W. G. Sombroek and I. S. Zonneveld Netherlands Soil Survey Institute, Wageningen A/Gr /3TI.O' SOIL SURVEY PAPERS No. 5 ANCIENT DUNE FIELDS AND FLUVIATILE DEPOSITS IN THE RIMA-SOKOTO RIVER BASIN (N.W. NIGERIA) Geomorphologie phenomena in relation to Quaternary changes in climate at the southern edge of the Sahara W. G. Sombroek and I. S. Zonneveld Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU ! World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued ! information available for consultation, following Fair Use ' Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the j Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the i originators. For questions please contact soil.isricOwur.nl \ indicating the item reference number concerned. ! J SOIL SURVEY INSTITUTE, WAGENINGEN, THE NETHERLANDS — 1971 3TV9 Dr. I. S. Zonneveld was chief of the soils and land evaluation section of the Sokoto valley project and is at present Ass. Professor in Ecology at the International Institute for Aerial Survey and Earth Science (ITC) at Enschede, The Netherlands (P.O. Box 6, Enschede). Dr. W. G. Sombroek was a member of the same soils and evaluation section and is at present Project Manager of the Kenya Soil Survey Project, which is being supported by the Dutch Directorate for International Technical Assistance (P.O. Box 30028, Nairobi). The opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication are the authors' own personal views, and may not be taken as reflecting the official opinion or policies of either the Nigerian Authorities or the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. -

Bauchi State

RAP FOR THE PROPOSED REHABILITATION OF 19 KM LIMAN KATAGUM – LUDA – LEKKA RURAL ROAD, BAUCHI STATE Public Disclosure Authorized RURAL ACCESS AND AGRICULTURAL MARKETING PROJECT (RAAMP), BAUCHI STATE (World Bank Assisted) Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) DRAFT FINAL REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED REHABILITATION OF THE 19KM Public Disclosure Authorized LIMAN KATAGUM – LUDA – LEKKA RURAL ACCESS ROAD IN BAUCHI STATE Bauchi State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) Rural Access and Agricultural Marketing Project (RAAMP) Public Disclosure Authorized OCTOBER, 2019. RAP FOR THE PROPOSED REHABILITATION OF 19 KM LIMAN KATAGUM – LUDA – LEKKA RURAL ROAD, BAUCHI STATE Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................................... vii ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 15 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................... -

Nigeria Hotspots Location by State Platform Cholera Bauchi State West and Central Africa

Cholera - Nigeria hotspots location by state Platform Cholera Bauchi State West and Central Africa Katagum Jigawa Gamawa Zaki Gamawa Yobe Itas Itas/Gadau Hotspots typology in the State Jama'are Jamao�oareAzare Damban Hotspot type T.1: High priority area with a high frequency Katagum Damban and a long duration. Kano Shira Shira Giade Hotspot type T.2: Giade Misau Misau Medium priority area with a moderate frequency and a long duration Warji Darazo Warji Ningi Darazo Ningi Hotspots distribution in the State Ganjuwa Ganjuwa 10 8 Bauchi Hotspots Type 1 Hotspots Type 2 Kirifi Toro Kirfi Gombe Bauchi Ningi Alkaleri Itas/Gadau Alkaleri Dass Shira Damban Katagum Kaduna Bauchi Ganjuwa Toro Darazo Misau Jama'are Warji Gamawa Toro Dass Kirfi Tafawa-Balewa Giade Dass Tafawa-Balewa Alkaleri Legend Tafawa-Balewa Bogoro Countries State Main roads Bogoro Plateau XXX LGA (Local Governmental Area) Hydrography Taraba XXX Cities (State capital, LGA capital, and other towns) 0 70 140 280 420 560 Kilometers Date of production: January 21, 2016 Source: Ministries of Health of the countries members of the Cholera platform Contact : Cholera project - UNICEF West and Central Africa Regionial Office (WCARO) Feedback : Coordination : Julie Gauthier | [email protected] Information management : Alca Kuvituanga | [email protected] : of support the With The epidemiological data is certified and shared by national authorities towards the cholera platform members. Geographical names, designations, borders presented do not imply any official recognition nor approval from none of the cholera platform members . -

Influence of Arabic Poetry on the Composition and Dating of Fulfulde Jihad Poetry in Yola* (Nigeria)

INFLUENCE OF ARABIC POETRY ON THE COMPOSITION AND DATING OF FULFULDE JIHAD POETRY IN YOLA* (NIGERIA) Anneke Breedveld** 1. Introduction One of the significant contexts of use of Arabic script in Africa is the large amount of manuscripts in Fulfulde, inspired especially by Sheehu Usman dan Fodio. The writings of this pivotal political and religious leader and his contemporaries have been revered by his followers, and thus ample numbers have survived until the present day. Being Muslims and inspired by Arabic poetry, Usman dan Fodio’s contemporaries have used the Arabic script and metre to write up their compositions in various languages. The power of the Fulbe states in West Africa was closely associated with the Fulbe’s ‘ownership’ of Islam. Their aversion to the colonial powers who undermined their ruling position has since also led to a massive rejection of Western and Christian education by successive generations of Fulbe (Breedveld 2006; Regis 1997). Most Muslim children do learn to read and write Arabic in the Qurʾanic schools, resulting in widespread use of the Arabic script in Fulbe societies until today. The aim of this paper is to present initial results from the investigation of the jihad poetry composed in Fulfulde which is now available in Yola, Nigeria, and is, for the purpose of this paper dubbed the Yola collection. This collection contains 93 manuscripts of copied Fulfulde poems by Usman dan Fodio and his contemporaries and is at present privately owned by a family (see below). First, the present paper gives a brief introduction to the main poet, Usman dan Fodio, and his contemporaries are named. -

The Problems of Nigerian Education and National Unity

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1980 The Problems of Nigerian Education and National Unity Osilama Thomas Obozuwa Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Obozuwa, Osilama Thomas, "The Problems of Nigerian Education and National Unity" (1980). Dissertations. 2013. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2013 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 Osilama Thomas Obozuwa THE PROBLEMS OF NIGERIAN EDUCATION AND NATIONAL UNITY BY OSILAMA THOMAS OBOZUWA A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 1980 (c) 1980 OSILAMA THOMAS OBOZUWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a usual practice to acknowledge at least the direct help that one has received in the writing of a dissertation. It is impossible to mention everyone who helped to make the writing of this dissertation a success. My sincere thanks to all those whose names are not mentioned here. My deepest thanks go to the members of my dissertation committee: Fr. Walter P. Krolikowski, S. J., the Director, who not only served as my mentor for three years, but suggested to me the topic of this dissertation and zealously assisted me in the research work; Drs. -

Redalyc.Characteristics of Irrigation Tube Wells on Major River Flood

Ambiente & Água - An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Science ISSN: 1980-993X [email protected] Universidade de Taubaté Brasil Abubakar Sadiq, Abdullahi; Abubakar Amin, Sunusi; Ahmad, Desa; Gana Umara, Baba Characteristics of irrigation tube wells on major river flood plains in Bauchi State, Nigeria Ambiente & Água - An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Science, vol. 9, núm. 4, octubre-diciembre, 2014, pp. 603-609 Universidade de Taubaté Taubaté, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=92832359004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Ambiente & Água - An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Science ISSN 1980-993X – doi:10.4136/1980-993X www.ambi-agua.net E-mail: [email protected] Characteristics of irrigation tube wells on major river flood plains in Bauchi State, Nigeria doi: 10.4136/ambi-agua.1314 Received: 12 Feb. 2014; Accepted: 05 Sep. 2014 Abdullahi Abubakar Sadiq1*; Sunusi Abubakar Amin1; Desa Ahmad2; Baba Gana Umara3 1Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATB), PMB 0248 Bauchi, Nigeria Agricultural and Bioresource Engineering Department 2Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Selangor, DE, Malaysia Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering 3University of Maiduguri, Nigeria Department of Agricultural and Environmental Engineering *Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Water for traditional irrigation on flood-plains in Bauchi State is obtained from the Jama’are, Gongola and Komadugu river systems. -

Local Government Areas of Bauchi State

International Journal of Engineering and Modern Technology ISSN 2504-8848 Vol. 1 No.8 2015 www.iiardpub.org An Overview of Lignocellulose in Twenty (20) Local Government Areas of Bauchi State 1Mustapha D. Ibrahim and 2Ahmad Abdurrazzaq 1Department of Chemical Engineering, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi, Bauchi State, Nigeria 2Department of Chemical Engineering Technology, Federal Polytechnic Mubi, Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria 1E-mail: [email protected], 2E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In the past few decades, there has been an increasing research interest in the value of lignocellulosic material. Lignocellulose biomass abundant holds remarkable high potentials that will go a long way in solving environmental, domestic and industrial problems if harnessed. The overview looked into only six (6) types of lignocellulose which comprised of sugar cane bagasse, corn stover, groundnut shell, sorghum residue, millet residue, and rice straw in Bauchi State. Research method adopted was by analysis of variance and percentile. The quantity of lignocelluloses studied i.e. Sugarcane bagasse, corn stover, groundnut shell, millet residue, sorghum residue and rice straw were found to be (936.7; 539,079.9; 144,352.0; 784,419.5; 905,370.6; and 73,335.5) tones/annum respectively. However, lignocellulose as a source of bioenergy in form of ethanol, the findings further revealed the estimated quantity of ethanol from sugarcane bagasse, corn stover, rice straw, sorghum, groundnut shell and millet to be at 142,462.7; 78,317,527.9; 9,339,055.9; 147,973,770.9; 18,022,347.2; and 62,322,129.3 liters/annum respectively. Keywords: lignocellulose; production capacity; energy; biomass; Bauchi INTRODUCTION Bauchi State; a state located between latitudes 9° 3´ and 12° 3´ north and longitudes 8° 50´ and 11° 0´ in the north-eastern part of Nigeria has a total land area of 49,119 km2 representing about 5.3% of the country’s total land mass and extents two distinct vegetation zones, namely the Sudan savannah and the Sahel savannah. -

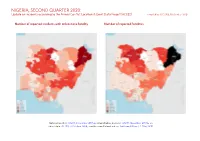

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 356 233 825 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 246 200 1257 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Protests 141 1 1 Explosions / Remote Methodology 3 77 67 855 violence Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 75 26 42 Strategic developments 18 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 913 527 2980 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.