Rhodamnia Rubescens (Benth.) Miq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Hundred Plant Species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java a Checklist Including Sundanese Names, Distribution and Use

Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman © 2010 Center for International Forestry Research. All rights reserved. Printed in Indonesia ISBN: 978-602-8693-22-6 Priyadi, H., Takao, G., Rahmawati, I., Supriyanto, B., Ikbal Nursal, W. and Rahman, I. 2010 Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java: a checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia. Photo credit: Hari Priyadi Layout: Rahadian Danil CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] www.cifor.cgiar.org Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) CIFOR advances human wellbeing, environmental conservation and equity by conducting research to inform policies and practices that affect forests in developing countries. CIFOR is one of 15 centres within the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). CIFOR’s headquarters are in Bogor, Indonesia. It also has offices in Asia, Africa and South America. | iii Contents Author biographies iv Background v How to use this guide vii Species checklist 1 Index of Sundanese names 159 Index of Latin names 166 References 179 iv | Author biographies Hari Priyadi is a research officer at CIFOR and a doctoral candidate funded by the Fonaso Erasmus Mundus programme of the European Union at Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. -

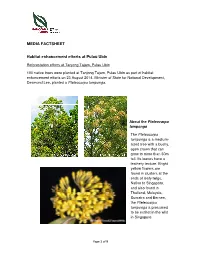

MEDIA FACTSHEET Habitat Enhancement Efforts at Pulau Ubin

MEDIA FACTSHEET Habitat enhancement efforts at Pulau Ubin Reforestation efforts at Tanjong Tajam, Pulau Ubin 100 native trees were planted at Tanjong Tajam, Pulau Ubin as part of habitat enhancement efforts on 23 August 2014. Minister of State for National Development, Desmond Lee, planted a Pteleocarpa lamponga. About the Pteleocarpa lamponga The Pteleocarpa lamponga is a medium- sized tree with a bushy, open crown that can grow to more than 30m tall. Its leaves have a leathery texture. Bright yellow flowers are found in clusters at the ends of leafy twigs. Native to Singapore, and also found in Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo, the Pteleocarpa lamponga is presumed to be extinct in the wild in Singapore. Page 1 of 9 Aphanamixis polystachya (Common names: Pasak Lingga, Amoora, Cikih, Kasai Paya, Kulim Burung) Growing up to 20m tall, the leaves of the Aphanamixis polystachya are oblong and leathery. Its sweetly scented flowers are cream, yellow or bronze in colour. Oil extracted from its seeds have medicinal properties and used externally for rheumatism. However, its fruits are poisonous. The Aphanamixis polystachya is classified as endangered in Singapore. Erythroxylum cuneatum (Common names: Wild Cocaine, Baka, Beluntas Bukit, Cinatamula, Inai Inai, Mahang Wangi, Medang Lenggundi, Medang Wangi) Page 2 of 9 Growing up to 45m tall, the Erythroxylum cuneatum Has flattened green twigs. Its tiny flowers grow in clusters of 1-8, and are white to light green in colour. Its fruits are bright red when ripe, and are eaten by mammals and porcupines. The Erythroxylum cuneatum is classified as common in Singapore and can be found in Changi, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and St John’s Island. -

In China: Phylogeny, Host Range, and Pathogenicity

Persoonia 45, 2020: 101–131 ISSN (Online) 1878-9080 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2020.45.04 Cryphonectriaceae on Myrtales in China: phylogeny, host range, and pathogenicity W. Wang1,2, G.Q. Li1, Q.L. Liu1, S.F. Chen1,2 Key words Abstract Plantation-grown Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) and other trees residing in the Myrtales have been widely planted in southern China. These fungal pathogens include species of Cryphonectriaceae that are well-known to cause stem Eucalyptus and branch canker disease on Myrtales trees. During recent disease surveys in southern China, sporocarps with fungal pathogen typical characteristics of Cryphonectriaceae were observed on the surfaces of cankers on the stems and branches host jump of Myrtales trees. In this study, a total of 164 Cryphonectriaceae isolates were identified based on comparisons of Myrtaceae DNA sequences of the partial conserved nuclear large subunit (LSU) ribosomal DNA, internal transcribed spacer new taxa (ITS) regions including the 5.8S gene of the ribosomal DNA operon, two regions of the β-tubulin (tub2/tub1) gene, plantation forestry and the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) gene region, as well as their morphological characteristics. The results showed that eight species reside in four genera of Cryphonectriaceae occurring on the genera Eucalyptus, Melastoma (Melastomataceae), Psidium (Myrtaceae), Syzygium (Myrtaceae), and Terminalia (Combretaceae) in Myrtales. These fungal species include Chrysoporthe deuterocubensis, Celoporthe syzygii, Cel. eucalypti, Cel. guang dongensis, Cel. cerciana, a new genus and two new species, as well as one new species of Aurifilum. These new taxa are hereby described as Parvosmorbus gen. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

Blair's Rainforest Inventory

Enoggera creek (Herston/Wilston) rainforest inventory Prepared by Blair Bartholomew 28-Jan-02 Botanical Name Common Name: tree, shrub, Derivation (Pronunciation) vine, timber 1. Acacia aulacocarpa Brown salwood, hickory/brush Acacia from Greek ”akakia (A), hê”, the shittah tree, Acacia arabica; (changed to Acacia ironbark/broad-leaved/black/grey which is derived from the Greek “akanth-a [a^k], ês, hê, (akê A)” a thorn disparrima ) wattle, gugarkill or prickle (alluding to the spines on the many African and Asian species first described); aulacocarpa from Greek “aulac” furrow and “karpos” a fruit, referring to the characteristic thickened transverse bands on the a-KAY-she-a pod. Disparrima from Latin “disparrima”, the most unlike, dissimilar, different or unequal referring to the species exhibiting the greatest difference from other renamed species previously described as A aulacocarpa. 2. Acacia melanoxylon Black wood/acacia/sally, light Melanoxylon from Greek “mela_s” black or dark: and “xulon” wood, cut wood, hickory, silver/sally/black- and ready for use, or tree, referring to the dark timber of this species. hearted wattle, mudgerabah, mootchong, Australian blackwood, native ash, bastard myall 3. Acmena hemilampra Broad-leaved lillypilly, blush satin Acmena from Greek “Acmenae” the nymphs of Venus who were very ash, water gum, cassowary gum beautiful, referring to the attractive flowers and fruits. A second source says that Acmena was a nymph dedicated to Venus. This derivation ac-ME-na seems the most likely. Finally another source says that the name is derived from the Latin “Acmena” one of the names of the goddess Venus. Hemilampra from Greek “hemi” half and “lampro”, bright, lustrous or shining, referring to the glossy upper leaf surface. -

Myrtle Rust Reviewed the Impacts of the Invasive Plant Pathogen Austropuccinia Psidii on the Australian Environment R

Myrtle Rust reviewed The impacts of the invasive plant pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment R. O. Makinson 2018 DRAFT CRCPLANTbiosecurity CRCPLANTbiosecurity © Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, 2018 ‘Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment’ is licenced by the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This Review provides background for the public consultation document ‘Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan’ available at www.apbsf.org.au Author contact details R.O. Makinson1,2 [email protected] 1Bob Makinson Consulting ABN 67 656 298 911 2The Australian Network for Plant Conservation Inc. Cite this publication as: Makinson RO (2018) Myrtle Rust reviewed: the impacts of the invasive pathogen Austropuccinia psidii on the Australian environment. Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra. Front cover: Top: Spotted Gum (Corymbia maculata) infected with Myrtle Rust in glasshouse screening program, Geoff Pegg. Bottom: Melaleuca quinquenervia infected with Myrtle Rust, north-east NSW, Peter Entwistle This project was jointly funded through the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre and the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. The Plant Biosecurity CRC is established and supported under the Australian Government Cooperative Research Centres Program. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This review of the environmental impacts of Myrtle Rust in Australia is accompanied by an adjunct document, Myrtle Rust in Australia – a draft Action Plan. The Action Plan was developed in 2018 in consultation with experts, stakeholders and the public. The intent of the draft Action Plan is to provide a guiding framework for a specifically environmental dimension to Australia’s response to Myrtle Rust – that is, the conservation of native biodiversity at risk. -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

Associations of Societies for Growing Australian Plants

Page 1 Associations of Societies for Growing Australian Plants – Rainforest Study Group – No.62 (7) June 2006 Associations of Societies for Growing Australian Plants ASGAP Rainforest Study Group NEWSLETTER No 62. (7) June 2006 ISSN 0729-5413 Annual Subscription $5, $10 overseas Photos: www.web-a-file.com Study Group Webpage (under construction): http://farrer.csu.edu.au/ASGAP/rainfor.html Email: [email protected] Address: Kris Kupsch, 28 Plumtree Pocket, Burringbar, Australia, 2483. Ph. (02) 66771466 Mob. 0439557438 Introduction ASGAP trip to Sydney Nov 2005 It has been a long while since I wrote a During my brief visit to Sydney in November newsletter, I apologise for taking so long. last year as part of an invitation to speak at a Since the last newsletter the family and I have SGAP meeting in Ermington, I got to do the moved back to the Wet Tropics. I now work following: as an Environmental Scientist undertaking 1. I was escorted by Cas Liber, ASGAP vegetation surveys and compiling Banksia Study Group leader. Cas environmental management plans for parts of toured me through the Botanic the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. This Gardens, his garden, among others. has been a rather large transition, leaving Many thanks to Cas and his family. behind my garden and all of my immediate 2. I visited Betty Rymers garden at plans in NSW; the job was too good to refuse. Kenthurst. Betty has a notable I wish everyone the best with their rainforest garden including a large endeavours and hope this newsletter was Brachychiton discolor, Dianella worth the wait. -

Australian Nursery Industry Myrtle Rust Management Plan 2011

Australian Nursery Industry Myrtle Rust (Uredo rangelii) Management Plan 2011 Developed for the Australian Nursery Industry Production Wholesale Retail Acknowledgements This Myrtle Rust Management Plan has been developed by the Nursery & Garden Industry Queensland (John McDonald - Nursery Industry Development Manager) for the Australian Nursery Industry. Version 01 February 2011 Photographs sourced from I&I NSW and Queensland DEEDI. Various sources have contributed to the content of this plan including: • Nursery Industry Accreditation Scheme Australia (NIASA) • BioSecure HACCP • Nursery Industry Guava Rust Plant Pest Contingency Plan • DEEDI Queensland Myrtle Rust Fact Sheets • I&I NSW Myrtle Rust Fact Sheets and Updates Preparation of this document has been financially supported by Nursery & Garden Industry Queensland, Nursery & Garden Industry Australia and Horticulture Australia Ltd. Published by Nursery & Garden Industry Australia, Sydney 2011 © Nursery & Garden Industry Queensland 2011 While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of contents, Nursery & Garden Industry Queensland accepts no liability for the information. For further information contact: John McDonald Industry Development Manager NGIQ Ph: 07 3277 7900 Email: [email protected] 2 Nursery Industry Myrtle Rust Management Plan - 2011 Table of Contents 1. Managing Myrtle Rust in the Australian Nursery Industry 4 2. Myrtaceae Family – Genera 5 3. Myrtle Rust (Uredo rangelii) 6 4. Known Hosts of Myrtle Rust in Australia 7 5. Fungicide Treatment 8 5.2 Myrtle Rust Fungicide Treatment Rotation Program 8 5.3 Fungicide Application 9 6. On-site Biosecurity Actions 9 6.1 Production Nursery 10 6.2 Propagation (specifics) 11 6.3 Greenlife Markets/Retailers 12 7. Monitoring and Inspection Sampling Protocol 12 7.1 Monitoring Process 12 7.2 Sampling Process 13 8. -

I Is the Sunda-Sahul Floristic Exchange Ongoing?

Is the Sunda-Sahul floristic exchange ongoing? A study of distributions, functional traits, climate and landscape genomics to investigate the invasion in Australian rainforests By Jia-Yee Samantha Yap Bachelor of Biotechnology Hons. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation i Abstract Australian rainforests are of mixed biogeographical histories, resulting from the collision between Sahul (Australia) and Sunda shelves that led to extensive immigration of rainforest lineages with Sunda ancestry to Australia. Although comprehensive fossil records and molecular phylogenies distinguish between the Sunda and Sahul floristic elements, species distributions, functional traits or landscape dynamics have not been used to distinguish between the two elements in the Australian rainforest flora. The overall aim of this study was to investigate both Sunda and Sahul components in the Australian rainforest flora by (1) exploring their continental-wide distributional patterns and observing how functional characteristics and environmental preferences determine these patterns, (2) investigating continental-wide genomic diversities and distances of multiple species and measuring local species accumulation rates across multiple sites to observe whether past biotic exchange left detectable and consistent patterns in the rainforest flora, (3) coupling genomic data and species distribution models of lineages of known Sunda and Sahul ancestry to examine landscape-level dynamics and habitat preferences to relate to the impact of historical processes. First, the continental distributions of rainforest woody representatives that could be ascribed to Sahul (795 species) and Sunda origins (604 species) and their dispersal and persistence characteristics and key functional characteristics (leaf size, fruit size, wood density and maximum height at maturity) of were compared.