CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the 3Rd GBIF Science Symposium Brussels, 18-19 April 2005

Proceedings of the 3rd GBIF Science Symposium Brussels, 18-19 April 2005 Tropical Biodiversity: Science, Data, Conservation Edited by H. Segers, P. Desmet & E. Baus Proceedings of the 3rd GBIF Science Symposium Brussels, 18-19 April 2005 Tropical Biodiversity: Science, Data, Conservation Edited by H. Segers, P. Desmet & E. Baus Recommended form of citation Segers, H., P. Desmet & E. Baus, 2006. ‘Tropical Biodiversity: Science, Data, Conservation’. Proceedings of the 3rd GBIF Science Symposium, Brussels, 18-19 April 2005. Organisation - Belgian Biodiversity Platform - Belgian Science Policy In cooperation with: - Belgian Clearing House Mechanism of the CBD - Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences - Global Biodiversity Information Facility Conference sponsors - Belgian Science Policy 1 Table of contents Research, collections and capacity building on tropical biological diversity at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences .........................................................................................5 Van Goethem, J.L. Research, Collection Management, Training and Information Dissemination on Biodiversity at the Royal Museum for Central Africa .......................................................................................26 Gryseels, G. The collections of the National Botanic Garden of Belgium ....................................................30 Rammeloo, J., D. Diagre, D. Aplin & R. Fabri The World Federation for Culture Collections’ role in managing tropical diversity..................44 Smith, D. Conserving -

Five Hundred Plant Species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java a Checklist Including Sundanese Names, Distribution and Use

Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman © 2010 Center for International Forestry Research. All rights reserved. Printed in Indonesia ISBN: 978-602-8693-22-6 Priyadi, H., Takao, G., Rahmawati, I., Supriyanto, B., Ikbal Nursal, W. and Rahman, I. 2010 Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java: a checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia. Photo credit: Hari Priyadi Layout: Rahadian Danil CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] www.cifor.cgiar.org Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) CIFOR advances human wellbeing, environmental conservation and equity by conducting research to inform policies and practices that affect forests in developing countries. CIFOR is one of 15 centres within the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). CIFOR’s headquarters are in Bogor, Indonesia. It also has offices in Asia, Africa and South America. | iii Contents Author biographies iv Background v How to use this guide vii Species checklist 1 Index of Sundanese names 159 Index of Latin names 166 References 179 iv | Author biographies Hari Priyadi is a research officer at CIFOR and a doctoral candidate funded by the Fonaso Erasmus Mundus programme of the European Union at Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

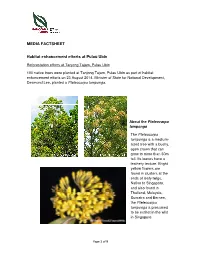

MEDIA FACTSHEET Habitat Enhancement Efforts at Pulau Ubin

MEDIA FACTSHEET Habitat enhancement efforts at Pulau Ubin Reforestation efforts at Tanjong Tajam, Pulau Ubin 100 native trees were planted at Tanjong Tajam, Pulau Ubin as part of habitat enhancement efforts on 23 August 2014. Minister of State for National Development, Desmond Lee, planted a Pteleocarpa lamponga. About the Pteleocarpa lamponga The Pteleocarpa lamponga is a medium- sized tree with a bushy, open crown that can grow to more than 30m tall. Its leaves have a leathery texture. Bright yellow flowers are found in clusters at the ends of leafy twigs. Native to Singapore, and also found in Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo, the Pteleocarpa lamponga is presumed to be extinct in the wild in Singapore. Page 1 of 9 Aphanamixis polystachya (Common names: Pasak Lingga, Amoora, Cikih, Kasai Paya, Kulim Burung) Growing up to 20m tall, the leaves of the Aphanamixis polystachya are oblong and leathery. Its sweetly scented flowers are cream, yellow or bronze in colour. Oil extracted from its seeds have medicinal properties and used externally for rheumatism. However, its fruits are poisonous. The Aphanamixis polystachya is classified as endangered in Singapore. Erythroxylum cuneatum (Common names: Wild Cocaine, Baka, Beluntas Bukit, Cinatamula, Inai Inai, Mahang Wangi, Medang Lenggundi, Medang Wangi) Page 2 of 9 Growing up to 45m tall, the Erythroxylum cuneatum Has flattened green twigs. Its tiny flowers grow in clusters of 1-8, and are white to light green in colour. Its fruits are bright red when ripe, and are eaten by mammals and porcupines. The Erythroxylum cuneatum is classified as common in Singapore and can be found in Changi, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and St John’s Island. -

In China: Phylogeny, Host Range, and Pathogenicity

Persoonia 45, 2020: 101–131 ISSN (Online) 1878-9080 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2020.45.04 Cryphonectriaceae on Myrtales in China: phylogeny, host range, and pathogenicity W. Wang1,2, G.Q. Li1, Q.L. Liu1, S.F. Chen1,2 Key words Abstract Plantation-grown Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) and other trees residing in the Myrtales have been widely planted in southern China. These fungal pathogens include species of Cryphonectriaceae that are well-known to cause stem Eucalyptus and branch canker disease on Myrtales trees. During recent disease surveys in southern China, sporocarps with fungal pathogen typical characteristics of Cryphonectriaceae were observed on the surfaces of cankers on the stems and branches host jump of Myrtales trees. In this study, a total of 164 Cryphonectriaceae isolates were identified based on comparisons of Myrtaceae DNA sequences of the partial conserved nuclear large subunit (LSU) ribosomal DNA, internal transcribed spacer new taxa (ITS) regions including the 5.8S gene of the ribosomal DNA operon, two regions of the β-tubulin (tub2/tub1) gene, plantation forestry and the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) gene region, as well as their morphological characteristics. The results showed that eight species reside in four genera of Cryphonectriaceae occurring on the genera Eucalyptus, Melastoma (Melastomataceae), Psidium (Myrtaceae), Syzygium (Myrtaceae), and Terminalia (Combretaceae) in Myrtales. These fungal species include Chrysoporthe deuterocubensis, Celoporthe syzygii, Cel. eucalypti, Cel. guang dongensis, Cel. cerciana, a new genus and two new species, as well as one new species of Aurifilum. These new taxa are hereby described as Parvosmorbus gen. -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia Submitted in accordance with Foreign Assistance Act Sections 118/119 February 20, 2004 Prepared for USAID/Indonesia Jl. Medan Merdeka Selatan No. 3-5 Jakarta 10110 Indonesia Prepared by Steve Rhee, M.E.Sc. Darrell Kitchener, Ph.D. Tim Brown, Ph.D. Reed Merrill, M.Sc. Russ Dilts, Ph.D. Stacey Tighe, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures............................................................................................................................... vii Acronyms....................................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... xvii 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................1- 1 2. Legislative and Institutional Structure Affecting Biological Resources...............................2 - 1 2.1 Government of Indonesia................................................................................................2 - 2 2.1.1 Legislative Basis for Protection and Management of Biodiversity and -

The Impact of Anchored Phylogenomics and Taxon Sampling on Phylogenetic Inference in Narrow-Mouthed Frogs (Anura, Microhylidae)

Cladistics Cladistics (2015) 1–28 10.1111/cla.12118 The impact of anchored phylogenomics and taxon sampling on phylogenetic inference in narrow-mouthed frogs (Anura, Microhylidae) Pedro L.V. Pelosoa,b,*, Darrel R. Frosta, Stephen J. Richardsc, Miguel T. Rodriguesd, Stephen Donnellane, Masafumi Matsuif, Cristopher J. Raxworthya, S.D. Bijug, Emily Moriarty Lemmonh, Alan R. Lemmoni and Ward C. Wheelerj aDivision of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA; bRichard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA; cHerpetology Department, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; dDepartamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociencias,^ Universidade de Sao~ Paulo, Rua do Matao,~ Trav. 14, n 321, Cidade Universitaria, Caixa Postal 11461, CEP 05422-970, Sao~ Paulo, Sao~ Paulo, Brazil; eCentre for Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; fGraduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; gSystematics Lab, Department of Environmental Studies, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, India; hDepartment of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA; iDepartment of Scientific Computing, Florida State University, Dirac Science Library, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4120, USA; jDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA Accepted 4 February 2015 Abstract Despite considerable progress in unravelling the phylogenetic relationships of microhylid frogs, relationships among subfami- lies remain largely unstable and many genera are not demonstrably monophyletic. -

View Preprint

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 30 March 2017. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/3077), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Oliver PM, Iannella A, Richards SJ, Lee MSY. 2017. Mountain colonisation, miniaturisation and ecological evolution in a radiation of direct-developing New Guinea Frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) PeerJ 5:e3077 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3077 Mountain colonisation, miniaturisation and ecological evolution in a radiation of direct developing New Guinea Frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) Paul M Oliver Corresp., 1 , Amy Iannella 2 , Stephen J Richards 3 , Michael S.Y Lee 3, 4 1 Division of Ecology and Evolution, Research School of Biology & Centre for Biodiversity Analysis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 3 South Australian Museum, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 4 School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia Corresponding Author: Paul M Oliver Email address: [email protected] Aims. Mountain ranges in the tropics are characterised by high levels of localised endemism, often-aberrant evolutionary trajectories, and some of the world’s most diverse regional biotas. Here we investigate the evolution of montane endemism, ecology and body size in a clade of direct-developing frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) from New Guinea. Methods. Phylogenetic relationships were estimated from a mitochondrial molecular dataset using Bayesian and maximum likelihood approaches. Ancestral state reconstruction was used to infer the evolution of elevational distribution, ecology (indexed by male calling height), and body size, and phylogenetically corrected regression was employed to examine the relationships between these three traits. -

Two New Frog Species from the Foja Mountains in Northwestern New Guinea (Amphibia, Anura, Microhylidae)

68 (2): 109 –122 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2018. 28.5.2018 Two new frog species from the Foja Mountains in north western New Guinea (Amphibia, Anura, Micro hylidae) Rainer Günther 1, Stephen Richards 2 & Burhan Tjaturadi 3 1 Museum für Naturkunde, Invalidenstr. 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] — 2 Herpetology Department, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia; [email protected] — 3 Conservation Inter- national – Papua Program. Current address: Center for Environmental Studies, Sanata Dharma University (CESSDU), Yogyakarta, Indonesia; [email protected] Accepted January 18, 2018. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/vertebrate-zoology on May 28, 2018. Editor in charge: Raffael Ernst Abstract Two new microhylid frogs in the genera Choerophryne and Oreophryne are described from the Foja Mountains in Papua Province of Indonesia. Both are small species (males 15.9 – 18.5 mm snout-urostyle length [SUL] and 21.3 – 22.9 mm SUL respectively) that call from elevated positions on foliage in primary lower montane rainforest. The new Choerophryne species can be distinguished from all congeners by, among other characters, a unique advertisement call consisting of an unpulsed (or very finely pulsed) peeping note last- ing 0.29 – 0.37 seconds. The new Oreophryne species belongs to a group that has a cartilaginous connection between the procoracoid and scapula and rattling advertisement calls. Its advertisement call is a loud rattle lasting 1.2 – 1.5 s with a note repetition rate of 11.3 – 11.7 notes per second. Kurzfassung Es werden zwei neue Engmaulfrösche der Gattungen Choerophryne und Oreophryne aus den Foja-Bergen in der Papua Provinz von Indonesien beschrieben. -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

Repeated Evolution of Carnivory Among Indo-Australian Rodents

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12871 Repeated evolution of carnivory among Indo-Australian rodents Kevin C. Rowe,1,2 Anang S. Achmadi,3 and Jacob A. Esselstyn4,5 1Sciences Department, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Australia 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Research Center for Biology, Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Cibinong, Jawa Barat, Indonesia 4Museum of Natural Science, 119 Foster Hall, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 5Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 Received February 1, 2015 Accepted January 12, 2016 Convergent evolution, often observed in island archipelagos, provides compelling evidence for the importance of natural selection as a generator of species and ecological diversity. The Indo-Australian Archipelago (IAA) is the world’s largest island system and encompasses distinct biogeographic units, including the Asian (Sunda) and Australian (Sahul) continental shelves, which together bracket the oceanic archipelagos of the Philippines and Wallacea. Each of these biogeographic units houses numerous endemic rodents in the family Muridae. Carnivorous murids, that is those that feed on animals, have evolved independently in Sunda, Sulawesi (part of Wallacea), the Philippines, and Sahul, but the number of origins of carnivory among IAA murids is unknown. We conducted a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of carnivorous murids of the IAA, combined with estimates of ancestral states for broad diet categories (herbivore, omnivore, and carnivore) and geographic ranges. These analyses demonstrate that carnivory evolved independently four times after overwater colonization, including in situ origins on the Philippines, Sulawesi, and Sahul. In each biogeographic unit the origin of carnivory was followed by evolution of more specialized carnivorous ecomorphs such as vermivores, insectivores, and amphibious rats.