At the Crossroads of Time – the Story of Operational Training Unit 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Search for Continental Security

THE SEARCH FOR CONTINENTAL SECURITY: The Development of the North American Air Defence System, 1949 to 1956 By MATTHEW PAUL TRUDGEN A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 12, 2011 Copyright © Matthew Paul Trudgen, 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the development of the North American air defence system from the beginning of the Cold War until 1956. It focuses on the political and diplomatic dynamics behind the emergence of these defences, which included several radar lines such as the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line as well as a number of initiatives to enhance co-operation between the United States Air Force (USAF) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). This thesis argues that these measures were shaped by two historical factors. The first was several different conceptions of what policy on air defence best served the Canadian national interest held by the Cabinet, the Department of External Affairs, the RCAF and the Other Government Departments (OGDs), namely Transport, Defence Production and Northern Affairs. For the Cabinet and External Affairs, their approach to air defence was motivated by the need to balance working with the Americans to defend the continent with the avoidance of any political fallout that would endanger the government‘s chance of reelection. Nationalist sentiments and the desire to ensure that Canada both benefited from these projects and that its sovereignty in the Arctic was protected further influenced these two groups. On the other hand, the RCAF was driven by a more functional approach to this issue, as they sought to work with the USAF to develop the best air defence system possible. -

Air Chief Marshal Frank Miller – a Civilian and Military Leader

HISTORY MILITARY DND Photo PL-52817 In 1951, Princess Elizabeth and The Duke of Edinburgh inspect RCAF Station Trenton and the commemorative gate to the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a wartime initiative of which Frank Miller was very much a part. Air Chief Marshal FranK Miller – A CIVILIAN AND Military LEADER by Ray Stouffer Introduction that such an exercise has not been undertaken previously says much about the lack of scholarly interest in the Cold War n Thursday, 28 April 1960, the Ottawa Citizen RCAF generally, and the dearth of biographies of senior wrote that Frank Miller, the former air marshal, Canadian airmen specifically. As remarkable as Miller’s career and, more recently, the Deputy Minister (DM) was is the fact that it is today largely unknown and therefore of National Defence, had become the unappreciated. Comprehending Miller’s military and civilian Diefenbaker Government’s choice as Chairman service not only explains why he was selected as Chairman of ofO the Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC), replacing General the COSC, it also addresses the larger question of military Charles Foulkes. Miller’s 24 years of service in the Royal leadership in peacetime. It is proposed that those responsible Canadian Air Force (RCAF) “…[had] given him a valuable for Miller’s selection felt that he possessed the requisite store of knowledge of all aspects of defence.” 1 As DM, Miller leadership capabilities and understanding of the needs of a was “…hailed as one of the keenest and most incisive minds in peacetime military better than his peers. the Defence Department.”2 In the same article, it was implied that changes were necessary in Canada’s military that demanded To support this argument, this article focuses upon two Miller’s experience, management skills, and leadership. -

Aviation Occurrence Report Collision with Snowbank Truro Flying Club Cessna Aircraft Company C152 C-GREJ Debert, Nova Scotia 17 December 1994

AVIATION OCCURRENCE REPORT COLLISION WITH SNOWBANK TRURO FLYING CLUB CESSNA AIRCRAFT COMPANY C152 C-GREJ DEBERT, NOVA SCOTIA 17 DECEMBER 1994 REPORT NUMBER A94A0242 MANDATE OF THE TSB The Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act provides the legal framework governing the TSB's activities. Basically, the TSB has a mandate to advance safety in the marine, pipeline, rail, and aviation modes of transportation by: ! conducting independent investigations and, if necessary, public inquiries into transportation occurrences in order to make findings as to their causes and contributing factors; ! reporting publicly on its investigations and public inquiries and on the related findings; ! identifying safety deficiencies as evidenced by transportation occurrences; ! making recommendations designed to eliminate or reduce any such safety deficiencies; and ! conducting special studies and special investigations on transportation safety matters. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. However, the Board must not refrain from fully reporting on the causes and contributing factors merely because fault or liability might be inferred from the Board's findings. INDEPENDENCE To enable the public to have confidence in the transportation accident investigation process, it is essential that the investigating agency be, and be seen to be, independent and free from any conflicts of interest when it investigates accidents, identifies safety deficiencies, and makes safety recommendations. Independence is a key feature of the TSB. The Board reports to Parliament through the President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada and is separate from other government agencies and departments. Its independence enables it to be fully objective in arriving at its conclusions and recommendations. -

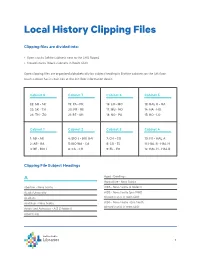

Local History Clipping Files

Local History Clipping Files Clipping files are divided into: • Open stacks (white cabinets next to the LHG Room) • Closed stacks (black cabinets in Room 440) Open clipping files are organized alphabetically by subject heading in 8 white cabinets on the 4th floor (each cabinet has its own key at the 4th floor information desk): Cabinet 8 Cabinet 7 Cabinet 6 Cabinet 5 22: SH - SK 19: PA - PR 16: LO - MO 13: HAL R - HA 23: SK - TH 20: PR - RE 17: MU - NO 14: HA - HO 24: TH - ZO 21: RE - SH 18: NO - PA 15: HO - LO Cabinet 1 Cabinet 2 Cabinet 3 Cabinet 4 1: AB - AR 4: BIO J - BIO U-V 7: CH - CO 10: FO - HAL A 2: AR - BA 5: BIO WA - CA 8: CO - EL 11: HAL B - HAL H 3: BE - BIO I 6: CA - CH 9: EL - FO 12: HAL H - HAL R Clipping File Subject Headings A Aged - Dwellings Agriculture - Nova Scotia Abortion - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia (2 folders) Acadia University AIDS - Nova Scotia (pre-1990) Acadians (closed stacks in room 440) Acid Rain - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia - Eric Smith (closed stacks in room 440) Actors and Actresses - A-Z (3 folders) Advertising 1 Airlines Atlantic Institute of Education Airlines - Eastern Provincial Airways (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Atlantic School of Theology Airplane Industry Atlantic Winter Fair (closed stacks in room 440) Airplanes Automobile Industry and Trade - Bricklin Canada Ltd. Airports (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Algae (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Canadian Motor Ambulances Industries (closed stacks in room 440) Amusement Parks (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Lada (closed stacks in room 440) Animals Automobile Industry and Trade - Nova Scotia Animals, Treatment of Automobile Industry and Trade - Volvo (Canada) Ltd. -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

The Story of Operational Training Unit 31 Debert

The Story Of Operational Unit 31, RCAF Station Debert , Under The British Commonwealth Training Plan By Major (Ret’d) G.D. Madigan Disclaimer The conclusions and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author cultivated in the freedom of expression and of an academic environment. Gerry (GD) Madigan, CD1, MA is a retired logistician, Canadian Armed Forces. Major (Retired) Madigan’s career spans 28 Years as a finance officer. His notable postings included time served at National Defence Headquarters, CFB Europe, Maritime Canada and the First Gulf War as comptroller in Qatar. He is a graduate of the Royal Military College of Canada, Kingston Ontario, and War Studies Program. 17 January 2011 This paper has been accepted for publication 19 January 2011 in the Canadian Aviation Historical Society Journal (Spring 2011) Major William Marsh Editor 1 Introduction In the hurly burly of early World War II, Canada helped lay the foundation of ultimate victory. Canada’s greatest contribution in that war was arguably the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). But really it was just one of three efforts; the others being the build up of the Royal Canadian Navy to the third largest in the world and the fielding of a Canadian Army in Western Europe and Italy. Canada’s war effort was therefore a triad of Canadian military power that greatly contributed to an Allied victory in World War II. Canadians often underrate that contribution. But it was a great sacrifice of national treasure in the cost of lives and money that was disproportionate to our population, geography, and economy at the time. -

THE NORAD EXPERIENCE: Implications for International Space Surveillance Data Sharing

THE NORAD EXPERIENCE: Implications for International Space Surveillance Data Sharing Full Report James C. Bennett Published 1 August 2010 Prepared for the Secure World Foundation This report was prepared by James Bennett under contract to Secure World Foundation. The contents within reflect the author's personal views and research and not necessarily those of Secure World Foundation. SECURE WORLD FOUNDATION The NORAD Experience | 2 Contents 1. Summary .................................................................................................................................... 5 2. History of NORAD .................................................................................................................. 10 2.1. The Airspace Situational Awareness Problem in the Mid-20th Century 10 2.1.1. The Formational Influences of NORAD's Founders 10 2.1.2. Airspace Situational Awareness Before and in World War II 11 2.2. The Postwar Period in the North American Context 15 2.2.1. A Clean Sheet of Paper: The Military Cooperation Committee and the Air Interceptor and Warning Plan of 1946 15 2.2.2. Legacies of Suspicion: Overcoming Historical Barriers to Close U.S.-Canada Cooperation 19 2.3. Response to Crisis: From Air Warning Plan to NORAD 29 2.3.1. From Theoretical to Perceived Threat: LASHUP and PERMANENT 29 2.3.2. The Canadian Gap 31 2.3.3. Extending Awareness - The Mid-Canada Line and the Distant Early Warning Line 33 2.3.4. The Obstacle of Divided Command 36 2.4. Formational History of NORAD: Lessons Learned 38 3. The Operational Experience of NORAD .............................................................................. 41 3.1. NORAD Adapts 41 3.1.1. The Shift from Bomber to Missile Attack as Primary Threat 41 3.1.2. Differences Between the United States and Canada in Concepts of Deterrence 42 3.1.3. -

Veterans Recognition Awards Recipients 2016 – Short Bios

Veterans Recognition Awards Recipients 2016 – Short Bios LCdr Rob Alain In 1985, LCdr Rob Alain enrolled in the Regular Force of the Royal Canadian Navy as a Supply Technician. Following basic training at HMCS Cornwallis, NS, and trade training at CFB Borden, ON, he was posted to CFB Halifax, NS. Posted aboard HMCS PRESERVER from 1987 until 1990, he also served at CFB Greenwood, NS, (1990-1994), CFB Gagetown, NB, (1994-2000), and CFB Cold Lake, AB, (2000-2004). Promoted to Petty Officer, 1st Class in 2003, he was reassigned to the Royal Canadian Air Force and posted back to CFB Greenwood. In 2006 he was promoted to Master Warrant Officer and served at 12 Air Maintenance Squadron (AMS), 12 Wing Shearwater, NS as the Supply Administration Officer. In 2007, he transferred to the Air Reserve and was commissioned to the rank of Captain, serving as the Logistics Officer at 12 AMS Shearwater. In 2008, he moved to Prince Edward Island, and in 2010 transferred to the Canadian Forces Maritime Command Primary Reserve List (MARCOM PRL) and was attach posted to HMCS QUEEN CHARLOTTE as the Ship’s Logistics Officer. Appointed Executive Officer (XO) in July 2013, in February 2014, he transferred from the RCN PRL to the Naval Reserve (NAVRES). In July 2015, he was appointed Commanding Officer of HMCS Queen Charlotte. LCdr Alain has also completed two UN tours to the Golan Heights, and currently serves as Honorary Aide-de-Camp for the Lieutenant-Governor of PEI. Major Jeff Barrett Major Jeff Barrett joined the Canadian Armed Forces as a Regular Force Signal Officer in 2001. -

USAF Combat Airfields in Korea and Vietnam Daniel L

WINTER 2006 - Volume 53, Number 4 Forward Air Control: A Royal Australian Air Force Innovation Carl A. Post 4 USAF Combat Airfields in Korea and Vietnam Daniel L. Haulman 12 Against DNIF: Examining von Richthofen’s Fate Jonathan M. Young 20 “I Wonder at Times How We Keep Going Here:” The 1941-1942 Philippines Diary of Lt. John P. Burns, 21st Pursuit Squadron William H. Bartsch 28 Book Reviews 48 Fire in the Sky: Flying in Defense of Israel. By Amos Amir Reviewed by Stu Tobias 48 Australia’s Vietnam War. By Jeff Doyle, Jeffrey Grey, and Peter Pierce Reviewed by John L. Cirafici 48 Into the Unknown Together: The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight. By Mark Erickson Reviewed by Rick W. Sturdevant 49 Commonsense on Weapons of Mass Destruction. By Thomas Graham, Jr. Reviewed by Phil Webb 49 Fire From The Sky: A Diary Over Japan. By Ron Greer and Mike Wicks Reviewed by Phil Webb 50 The Second Attack on Pearl Harbor: Operation K and Other Japanese Attempts to Bomb America in World War II. By Steve Horn. Reviewed by Kenneth P. Werrell 50 Katherine Stinson Otero: High Flyer. By Neila Skinner Petrick Reviewed by Andie and Logan Neufeld 52 Thinking Effects: Effects-Based Methodology for Joint Operations. By Edward C. Mann III, Gary Endersby, Reviewed by Ray Ortensie 52 and Thomas R. Searle Bombs over Brookings: The World War II Bombings of Curry County, Oregon and the Postwar Friendship Between Brookings and the Japanese Pilot, Nobuo Fujita. By William McCash Reviewed by Scott A. Willey 53 The Long Search for a Surgical Strike: Precision Munitions and the Revolution in Military Affairs. -

President's Words

Newsletter March 2009 Kingston Amateur Radio Club 2009 Executive President: Les, VE3KFS Newsletter Editor: Joan Clarke [email protected] [email protected] Vice-Pres: Robert, VE3RPF Repeater Committee: [email protected] VE3KFS, Les Lindstrom [email protected] Treasurer: Bill, VA3OL [email protected] VA3GST, John Snasdell-Taylor [email protected] Secretary: Chip, VA3KGB va3kgb@rac .ca VA3KGB, Chip Chapman [email protected] Past-Pres: Tom, VE3UDO [email protected] VE3JCQ, John Wood [email protected] 2009 Committee Chairs Two Meter Net Manager: VE3MNE, Don Gilroy [email protected] VE3CLQ, Bill Nangle [email protected] P.O. Box 1402 Kingston Ontario K7L 5C6 http://www.ve3kbr.com VE3KAR The 2nd Repeater is now VE3KBR Operational VE3UEL 147.090(+) MHz VE3KER 146.94(-) MHz News Kingston Amateur NOTE FROM THE PRESIDENT (Les, VE3KFS) Tom Lloyd VA3ZE/ VE3UDO Silent Key The passing of Tom has really struck the Amateur community here in Kingston as the flood of mail on the Free list has shown. As a long standing member of the KARC Tom could always be counted on to provide guidance and help to his fellow Amateur. His support and hard work on such club efforts as the repeater, field day, Emergency services and Club picnics to mention just a few, were instrumental in the KARC success over many years. The celebration of Tom's life was very well attended by a majority of KARC members. Thanks to all who were able to attend. Don't forget the next club meeting on Wednesday, April 1st, 2009 7: 00 pm. at Smitty's From the Editor: This is a much smaller newsletter than you've been getting – not many articles coming in. -

NEOCLASSICAL REALISM and the AVRO CF-105 ARROW a Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive NEOCLASSICAL REALISM AND THE AVRO CF-105 ARROW A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Bryn Rees Copyright Bryn Rees, June 2016. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A5 OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the key decisions made by the Diefenbaker government leading to the cancellation of the CF-105 Avro Arrow in 1958 and 1959, and more particularly the domestic factors that influenced those decisions. -

SPACE and NATIONAL SECURITY

SPACE and NATIONAL SECURITY . Symposium at Las Vegas An important highlight of the 1962 Air Force Association Convention at Las Vegas, Nev., was the Symposium on Space and National Security, held at the Las Vegas Convention Center September 21 under the auspices of the Aerospace Education Foundation. Panel moderator was Sen. Howard W. Cannon, Democrat of Nevada, who also served as Convention General Chairman. Panelists included Dr. Arthur Kantrowitz, Vice President of the Avco Corp., and Director of the Avco-Everett Research Laboratory, Everett, Mass.; Air Marshal C. Roy Slemon, Royal Canadian Air Force, Deputy Commander in Chief, North American Air Defense Command; Dr. Edward C. Welsh, Executive Secre- tary, National Aeronautics and Space Council; and Gen. Bernard A. Schriever, Commander, Air Force Systems Command. Panelists' formal presentations were followed by a lively question -and- answer period. Following is a slightly condensed version of the Symposium proceedings.—The Editors "Let us not explore the heavens at the risk of our survival as free men on earth. Let us agree that shooting at the moon, like disarmament, is a means to an end, not the end in itself." Can We Afford Medieval Thinking in the Space Age? By US SENATOR HOWARD W. CANNON HE other day I ran across a bit of satire diculously impossible? Well, yes, I suppose it is, pertinent to a symposium on space and if anything can be called ridiculously impossible. TF national security, a parody on a pro- I suppose this turnabout technique probably posal for a new anti-ICBM system. It is would qualify. Yet who can say how and where called the "turnabout technique." It is described the last laughs will fall as man pushes the state as follows: of the art? "Consider a large array of rigidly fixed rocket Historically, a lot of people have eaten the engines, uniformly distributed in a band about words "ridiculously impossible." So consider, for the earth's equator.