Roman Roads to Prosperity: Persistence and Non-Persistence of Public Goods Provision∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culinary VCA 5 Days 2012

Culinary Cycle Adventure „Via Claudia Augusta“ Cycle along old Roman routes and enjoy ancient cuisine 2000 years ago the Roman emperor Claudius had this route from the Adriatic Sea to Augsburg built mainly for his supply troops and courier services. In the middle of the 1990s this Roman road has been revived. Nowadays thousands of travellers follow this Roman route by bike or foot on a more peaceful mission and in a more comfortable way. Thanks to numerous landmarks, museums, information centres and two historical milestones of Roman history they also get into Roman history. Not only the Roman road, but also ancient culinary art has been revived. The food and stimulants prevailing at the time of Emperor Augustus still make for a pleasurable culinary experience today. More than 30 chefs between Füssen and Nauders use Roman ingredients to whip up dishes that accompany you on a historic culinary journey. How about beef fillet, Roman style with golden wheat or a filet of wild hare with a barley- mushroom risotto? In a Nutshell / Distinctive Features Mostly paved cycling paths and rural roads as well as less travelled back roads and village roads; shuttle transfer to conveniently manage the two challenging mountain passes; also for children from the age of 12 (high amount of cycling enthusiasm required). Bookable as individual single tour, 5 days / 4 nights, approximately 130 kilometers Arrival Every Saturday from 19 May to 15 September 2012 Extra dates are available if group size exceeds 4 people Programme Day 1: Individual journey to Füssen or Landeck Respectively Visit the late medieval town of Füssen or Landeck, the westernmost town of the Tyrol, respectively. -

Attivita' Progettuali

Claudia Augusta è il nome dell’antica strada imperiale tracciata nel I sec.A.C. dal generale romano Druso e in seguito completata dal figlio, l’imperatore Claudio, allo scopo di mettere in comunicazione i porti adriatici con le pianure danubiane. Da Altino portava ad Augusta attraverso il Veneto, il Trentino, l’Alto Adige, il Tirolo e la Baviera. Per secoli essa ha costituito l’asse portante delle comunicazioni tra Sud e Nord, tra le regione adriatiche e le regione retiche, tra la cultura latina e quelle germanica. La costruzione di questa strada rese possibile uno scambio culturale ed economico oltre le Alpi e promosse mobilità, commercio ed economia in modo insistente. Il profilo storico e quello odierno della Via Claudia Augusta si riferiscono specialmente alla funzione di collegamento per lo sviluppo culturale, economico, turistico e sociale di territori e paesi lungo il suo percorso. Partendo da tale approccio è stato costruito il progetto Via Claudia Augusta, cofinanziato nell’ambito del Programma di iniziativa comunitaria Interreg IIIB – Spazio alpino cha ha per obiettivo la cooperazione transnazionale, lo sviluppo armonioso ed equilibrate dell’Unione, e l’integrazione territoriale. La strategia di bade del progetto Via Claudia Augusta è stata la promozione, su base transnazionale, del territorio interessato dall’antica strada romana coinvolgendo gli attori locali, le amministrazioni comunale e le associazioni nell’intendo di sviluppare un’immagine comune della Via, all’insegna dello sviluppo sostenibile e integrato delle risorse territoriali. L’obiettivo è stato pertanto quelle di promuovere e organizzare, nell’area attraversata da questa antica strada romana , azioni comuni in quattro settori di intervento; archeologia, cultura, turismo, marchio ed attività economiche. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Package Tours

Via Claudia Augusta Crossing the AlpsVia on the Claudia roman footsteps Augusta Crossing the Alps on the roman footsteps Package offers summer 2018 Package offers summer 2018 tour operator: inntours in collaboration with ... 2000 Jahre Gastlichkeit Via Claudia Augusta EWIV Transnational 2000 anni di ospitalità 0043.664.2.63.555 — [email protected] 2000 years of hospitality www.viaclaudia.org Overview Via Claudia Augusta – Initial Notes ................................................................................... 3 From Augsburg to Bolzano ................................................................................................ 4 - Variation “Classic“ .................................................................................. 4 - Variation “Sporty” ................................................................................... 6 From Augsburg to Riva del Garda ..................................................................................... 8 - Variation “Classic” .................................................................................. 8 - Variation “Sporty” ................................................................................. 10 From Augsburg to Verona ................................................................................................ 12 - Variation “Classic” ................................................................................ 12 - Variation “Sporty” ................................................................................. 14 From Augsburg via Verona -

Comment Franchir Les Montagnes Des Pyrénées Le Plus Aisément Possible

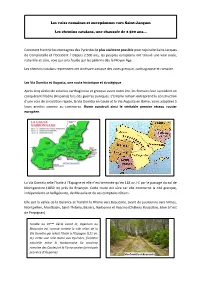

Les voies romaines et européennes vers Saint-Jacques Les chemins catalans, une chaussée de 2 500 ans… Comment franchir les montagnes des Pyrénées le plus aisément possible pour rejoindre Saint-Jacques de Compostelle et l’Occident ? Depuis 2 500 ans, les peuples européens ont trouvé une voie aisée, naturelle et sûre, voie qui sera foulée par les pèlerins dès le Moyen Âge… Les chemins catalans reprennent cet itinéraire antique des voies grecque, carthaginoise et romaine. Les Via Domitia et Augusta, une route historique et stratégique Après cinq siècles de colonies carthaginoise et grecque avant notre ère, les Romains leur succèdent en conquérant l’Ibérie (Hispanie) lors des guerres puniques. L’Empire romain entreprend la construction d’une voie de circulation rapide, la Via Domitia en Gaule et la Via Augusta en Ibérie, voies adaptées à leurs armées comme au commerce. Rome construit ainsi le véritable premier réseau routier européen. La Via Domitia relie l’Italie à l’Espagne et elle n’est terminée qu’en 118 av J-C par le passage du col de Montgenèvre (1850 m) près de Briançon. Cette route est sûre car elle contourne la cité grecque, indépendante et belligérante, de Massalia et de ses comptoirs côtiers. Elle suit la vallée de la Durance et franchit le Rhône vers Beaucaire, avant de poursuivre vers Nîmes, Montpellier, Montbazin, Saint-Thibéry, Béziers, Narbonne et Ruscino (Château Roussillon, 6 km à l’est de Perpignan). Fondée au VIIème siècle avant JC, Ugernum ou Beaucaire est connue comme la ville relais de la Via Domitia qui reliait l’Italie à l’Espagne (121 av. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Le Réseau Viaire Antique Du Tricastin Et De La Valdaine : Relecture Des Travaux Anciens Et Données Nouvelles Cécile Jung

Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles Cécile Jung To cite this version: Cécile Jung. Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles. Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise, Presse universitaire de la Méditerranée, 2009, pp.85-113. hal-00598526 HAL Id: hal-00598526 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00598526 Submitted on 7 Jun 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Le réseau viaire antique du Tricastin et de la Valdaine : relecture des travaux anciens et données nouvelles Cécile JUNG Résumé: À partir de travaux de carto-interprétation, de sondages archéologiques et de collectes de travaux anciens, le tracé de la voie d’Agrippa entre Montélimar et Orange est ici repris et discuté. Par ailleurs, l’analyse des documents planimétriques (cartes anciennes et photographies aériennes) et les résultats de plusieurs opérations archéologiques permettent de proposer un réseau de chemins probablement actifs dès l’Antiquité. Mots-clés: voie d’Agrippa, vallée du Rhône, analyse cartographique, centuriation B d’Orange, itinéraires antiques. Abstract: The layout of the Via Agrippa, between Montélimar and Orange, is studied and discussed in this article. -

Orbis Terrarum DATE: AD 20 AUTHOR: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Orbis Terrarum #118 TITLE: Orbis Terrarum DATE: A.D. 20 AUTHOR: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa DESCRIPTION: The profound difference between the Roman and the Greek mind is illustrated with peculiar clarity in their maps. The Romans were indifferent to mathematical geography, with its system of latitudes and longitudes, its astronomical measurements, and its problem of projections. What they wanted was a practical map to be used for military and administrative purposes. Disregarding the elaborate projections of the Greeks, they reverted to the old disk map of the Ionian geographers as being better adapted to their purposes. Within this round frame the Roman cartographers placed the Orbis Terrarum, the circuit of the world. There are only scanty records of Roman maps of the Republic. The earliest of which we hear, the Sardinia map of 174 B.C., clearly had a strong pictorial element. But there is some evidence that, as we should expect from a land-based and, at that time, well advanced agricultural people, subsequent mapping development before Julius Caesar was dominated by land survey; the earliest recorded Roman survey map is as early as 167-164 B.C. If land survey did play such an important part, then these plans, being based on centuriation requirements and therefore square or rectangular, may have influenced the shape of smaller-scale maps. This shape was also one that suited the Roman habit of placing a large map on a wall of a temple or colonnade. Varro (116-27 B.C.) in his De re rustica, published in 37 B.C., introduces the speakers meeting at the temple of Mother Earth [Tellus] as they look at Italiam pictam [Italy painted]. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Map 19 Raetia Compiled by H

Map 19 Raetia Compiled by H. Bender, 1997 with the assistance of G. Moosbauer and M. Puhane Introduction The map covers the central Alps at their widest extent, spanning about 160 miles from Cambodunum to Verona. Almost all the notable rivers flow either to the north or east, to the Rhine and Danube respectively, or south to the Po. Only one river, the Aenus (Inn), crosses the entire region from south-west to north-east. A number of large lakes at the foot of the Alps on both its north and south sides played an important role in the development of trade. The climate varies considerably. It ranges from the Mediterranean and temperate to permafrost in the high Alps. On the north side the soil is relatively poor and stony, but in the plain of the R. Padus (Po) there is productive arable land. Under Roman rule, this part of the Alps was opened up by a few central routes, although large numbers of mountain tracks were already in use. The rich mineral and salt deposits, which in prehistoric times had played a major role, became less vital in the Roman period since these resources could now be imported from elsewhere. From a very early stage, however, the Romans showed interest in the high-grade iron from Noricum as well as in Tauern gold; they also appreciated wine and cheese from Raetia, and exploited the timber trade. Ancient geographical sources for the region reflect a growing degree of knowledge, which improves as the Romans advance and consolidate their hold in the north. -

La Via Claudia Augusta in Veneto

La Via Claudia Augusta in Veneto La historia della Via Claudia Augusta, Storia e cultura, Natura e ambiente, Enogastronomia e turismo, Informazioni LA CITTA DI FELTRE ED IL FELTRINO............….....................................1 DA FELTRE AD TREVISO (Marca Trevigiana)........……......…….............4 TREVISO..........................................................................................…......15 DA TREVISO AD ALTINO...........…………………………………...............17 Per l'esattezza delle informazioni non è garanzia Le informazioni correnti sulla ammissione dei prezzi e pernottamento fondi disponibili attraverso Internet Links Gefördert aus Mitteln der Europäischen Union und des Freistaat Bayern, Programm LEADER+ im Rahmen eines transnationalen Kooperationsprojektes der Partner GAL Valsugana, Trentino,It. Und LAG Auerbergland, Bayern, D. LA CITTA DI FELTRE ED IL Contatto: Ass.ne il Fondaco per Feltre FELTRINO tel.0439/83879 (anche fax) dal martedì al venerdì dalle ore 9.30 alle ore 10.30 E-mail: INFOBOX fondacofeltre@ yahoo.it Ufficio Turistico Provinciale di Feltre Escursione Centro della Città Piazzetta Trento-Trieste 9 Via Mezzaterra, Piazza Maggiore e Palazzo I32032 Feltre – BL della Ragione Tel. 0439/2540 Da Porta Imperiale, chiamata anche Porta Fax 0439/2839 Castaldi, lungo la strada principale del e-mail feltre@ infodolomiti.it centro storico, Via Mezzaterra, con i www.infodolomiti.it bellissimi palazzi affrescati fino a Piazza Maggiore con il Palazzo della Ragione Parcheggi per autobus: visibile sulla destra. Lamon: ampio parcheggio -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath.