Oral History Interview with Margret Craver Withers, 1983-1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Combined Metalworking Techniques: Forged Elements and Chased Raised Shapes Bonnie Gallagher

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 1972 Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes Bonnie Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gallagher, Bonnie, "Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREATISE ON COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES i FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES TREATISE ON. COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES t FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES BONNIE JEANNE GALLAGHER CANDIDATE FOR THE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THE COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS OF THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUGUST ( 1972 ADVISOR: HANS CHRISTENSEN t " ^ <bV DEDICATION FORM MUST GIVE FORTH THE SPIRIT FORM IS THE MANNER IN WHICH THE SPIRIT IS EXPRESSED ELIEL SAARINAN IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER, WHO LONGED FOR HIS CHILDREN TO HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE THE EDUCATION HE NEVER HAD THE FORTUNE TO OBTAIN. vi PREFACE Although the processes of raising, forging, and chasing of metal have been covered in most technical books, to date there is no major source which deals with the functional and aesthetic requirements -

The Book Collection of Artist and Educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) Courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

YMeDaCa: READING LIST The book collection of artist and educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park. With special thanks to NAEA volunteers, Jane Carlton, Judith Padden, Sylvia Greenwood and Christine Parkinson. To visit: www.ysp.co.uk/naea BOOK TITLE AUTHOR Treasures of ancient America: the arts of pre-Columbian civilizations from Mexico to Peru S K Lothrop Neo-classical England Judy Marle Bronzes from the Deccan: Lalit Kala Nos. 3-4 Douglas Barrett Ancient Peruvian art [exhibition catalogue] Laing Art Gallery. Newcastle upon Tyne The art of the Canadian Eskimo W T Lamour & Jacques Brunet [trans] The American Indians : their archaeology and pre history Dean Snow Folk art of Asia, Australia, the Americas Helmuth Th. Bossert North America Wolfgang Haberland Sacred circles: two thousand years of north American Indian art [exhibition catalogue] Ralph T Coe People of the totem: the Indians of the Pacific North-West Norman Bencroft-Hunt Mexican art Justino Fernandez Mexican art Justino Fernandez Between continents/between seas: precolumbian art of Costa Rica Suzanne Abel-Vidor et al The art of ancient Mexico Franz Feuchtwanger Angkor: art and civilization Bernard Crosier The Maori: heirs of Tane David Lewis Cluniac art of the Romanesque period Joan Evans English romanesque art 1066-1200 [exhibition catalogue] Arts Council Oceanic art Alberto Cesace Ambesi 100 Master pieces: Mohammedan & oriental The Harvard outline and reading lists for Oriental Art. Rev.ed Benjamin Rowland Jr. Shock of recognition: landscape of English Romanticism, Dutch seventeenth-century school. American primitive Sandy Lesberg (ed) American Art: four exhibitions. -

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History

Proceedingsof the SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY 4 °4vv.es`Egi vI V°BkIAS VOLUME XXV, PART 1 (published 1950) PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY W. E. HARRISON & SONS, LTD., THE ANCIENT HOUSE, IPSWI611. The costof publishing this paper has beenpartially defrayedby a Grant from the Council for British Archeology. THE SUTTON HOO SHIP-BURIAL Recenttheoriesand somecommentsongeneralinterpretation By R. L. S. BRUCE-MITFORD, SEC. S.A. INTRODUCTION The Sutton Hoo ship-burial was discovered more than ten years ago. During these years especially since the end of the war in Europe has made it possible to continue the treatment and study of the finds and proceed with comparative research, its deep significance for general and art history, Old English literature and European archmology has become more and more evident. Yet much uncertainty prevails on general issues. Many questions cannot receive their final answer until the remaining mounds of the grave-field have been excavated. Others can be answered, or at any rate clarified, now. The purpose of this article is to clarify the broad position of the burial in English history and archmology. For example, it has been said that ' practically the whole of the Sutton Hoo ship-treasure is an importation from the Uppland province of Sweden. The great bulk of the work was produced in Sweden itself.' 1 Another writer claims that the Sutton Hoo ship- burial is the grave of a Swedish chief or king.' Clearly we must establish whether it is part of English archxology, or of Swedish, before we can start to draw from it the implications that we are impatient to draw. -

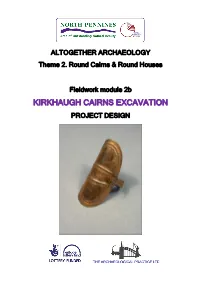

Kirkhaugh Cairns Excavation Project Design

ALTOGETHER ARCHAEOLOGY Theme 2. Round Cairns & Round Houses Fieldwork module 2b KIRKHAUGH CAIRNS EXCAVATION PROJECT DESIGN Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design. 2 Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design.. Contents General introduction 1. Introduction to the Kirkhaugh Cairns 2. Scope of this Document 3. Topography and Geology 4. Archaeological Background 5. Research Aims 6. The Cairns 7. Excavation objectives 8. Methods statement 9. Finds, Environmental Sampling and human remains 10. Report 11. Archive 12. Project team 13. Communications 14. Stages, Tasks and Timetable 15. Site access and on-site facilities 16. Health & Safety and Insurance 17. References Appendices (bound separately) 1. Altogether Archaeology standard Risk Assessment. 2. Kirkhaugh Cairns module-specific Risk Assessment. Front cover illustration. The gold ‘earring’, now considered more likely to have been worn as a hair braid or attached to clothing in some way, discovered by Herbert Maryon during his excavation of Kirkhaugh Cairn 1 in 1935. This is very rare find, and dates from the very earliest phase of metalworking in Britain, about 2,400BC. It is on display in the Great North Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne. 3 Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design. General introduction Altogether Archaeology, largely funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, is the North Pennines AONB Partnership’s community archaeology project. It enables volunteers to undertake practical archaeological projects with appropriate professional supervision and training. As well as raising the capacity of local groups to undertake research, the project makes a genuine contribution to our understanding of the North Pennines historic environment, thus contributing to future landscape management. -

Sciheritagecomplete

King’s Research Portal Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kandiah, M. D., & Cassar, M. (2014). Development of Science and Research applied to Cultural Heritage, 1947- 2007. Institute of Contemporary British History. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. -

Sutton Hoo Och Beowulf Lindqvist, Sune Fornvännen 94-110 Ingår I: Samla.Raa.Se SUTTON HOO OCH BEOWULF*

Sutton Hoo och Beowulf Lindqvist, Sune Fornvännen 94-110 http://kulturarvsdata.se/raa/fornvannen/html/1948_094 Ingår i: samla.raa.se SUTTON HOO OCH BEOWULF* Av Sune Lindqvist D'e.n 14 augusti 1939 godtog en engelsk domstol under handläggning av ett rättstall en bevisning av säregen art. Det gällde att avgöra äganderätten till ett planmässigt ur en forntida gravhög framgrävt fynd av utomordentligt vetenskapligt men också betydande materiellt värde. Vid Sutton Hoo, nära Ipswich på Suftolks kust, nordost om London, hade man uppdagat det rikaste gravinventarium, som över huvud grävts fram inom norra och mellersta Europa åtminstone allt sedan frankerkonungen Childerik 1:8 grav år 1653 öppnades vid Tournai i norra Frankrike. Ett klinkbyggt fartyg av 24 m:s längd och 4,5 m:s bredd — till for men närmast erinrande om den bekanta ekbåten från Nydam — hade sänkts ner i en ungefärligen mot dess djup svarande ränna, som man för ändamålet grävt i strandbräddens sand. I fartygets mittre del restes ett sadeltak av trä, stött mot relingarna, 5,8 m långt, i ömse ändar slutet av trekantiga gavelfält av trä, I övrigt hade hela skepps rummet fyllts ut till marknivån med den uppskottade sanden; det skedde förmodligen innan gravsättningen företogs. Allt gravgods, varav spår iakttagits, lades i varje fall samlat i kammaren, som efteråt doldes under en 20—24 m vid och 3 m hög kulle av grästorvor. Allt delta kunde noggrant iakttagas, ehuru träet upplösts och en dast efterlämnat en mörk avtärgning av kontaktytorna. Båtnitarna lågo kvar i tydliga rader. Gravrummet innehöll en rik vapenrustning — hjälm, sköld, svärd med gehäng, flera spjut och pilar in. -

Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw the Context of Invention in the Ancient World

Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw The Context of Invention in the Ancient World STEPHANIE DALLEY and JOHN PETER OLESON This article will present the cases for and against Archimedes as the origi- nal inventor of the most striking and famous device attributed to him, the water screw. It takes the form of a case study that focuses as much on the context and motives for the invention as on the possible inventor himself. In brief, an Archimedean water screw consists of a cylinder containing sev- eral continuous helical walls that, when the entire cylinder is rotated on its longitudinal axis, scoop up water at the open lower end and dump it out the upper end. Both Aage Drachmann and John Oleson have summarized the literary and archaeological evidence from the classical world suggesting that Archimedes (287–212 B.C.) was the first person to design and construct a mechanical water-raising screw, and they accept him as the inventor.1 Stephanie Dalley, on the other hand, reinterpreting a passage of cuneiform Akkadian and a statement by Strabo, has proposed that the water screw was Dr. Dalley is Shillito Research Fellow in Assyriology at the Oriental Institute and Somerville College, University of Oxford. She has published primary editions of cunei- form texts from excavations in Iraq and Syria and from museums in Britain, as well as specialized studies and more general books. She has translated all the Assyrian texts used in this article. Dr. Oleson is professor of Greek and Roman Studies at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. His areas of fieldwork and research include ancient hydraulic technology, Roman harbors and their construction, and the Roman Near East. -

Inside the Crucible

Historical Metallurgy Society News Issue 92 Summer 2016 Copper (with iron) and brass prills in a graphite crucible Editor Marcos Martinón-Torres Inside The Crucible Assistant Editors Loïc Boscher 2 �����������������������From the Chairman’s Desk Carlotta Gardner Matt Phelps 3 �����������������������Archaeometallurgy News María Teresa Plaza 10 ��������������������A Letter From��� Sudan Submissions Submissions to The Crucible are 12 ��������������������One Minute Interview - welcome at any time, but deadlines for each issue are 1st March, 1st July and �����������������������������María Filomena Guerra 1st November every year. Contributions can be sent in any format, but we prefer 14 ��������������������Meet Your Council - digital if possible. Jonathan Prius The Crucible thecrucible@hist-met�org 15 ��������������������Review c/o Marcos Martinón-Torres UCL Institute of Archaeology 31-34 Gordon Square 16 ��������������������Forthcoming Events London WC1H 0PY United Kingdom www.hist-met.org From the Chairman’s Desk he recent 2016 Annual General Meeting saw some will be made in the autumn edition. significant changes to the membership classes of HMS, T I have now received reports of the arrival of the reprinted as previewed in the last edition of The Crucible. As with copies of HM v47/2 and v48 on several continents, so I so much of the recent ‘behind-the-scenes’ activity, this is hope that all members have now received their copies. focused on the need to establish Historical Metallurgy Could any members for whom these are still missing online. It became clear during discussions with potential please contact me? All members are reminded to of the digital publishing partners that we needed to streamline need to keep the Membership Secretary informed of any our rather over-complex membership structure and lay changes of both postal and email addresses. -

The Column of Constantine at Constantinople: a Cultural History (330-1453 C.E.)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 The Column of Constantine at Constantinople: A Cultural History (330-1453 C.E.) Carey Thompson Wells The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2213 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE COLUMN OF CONSTANTINE AT CONSTANTINOPLE: A CULTURAL HISTORY (330-1453 C.E.) BY CAREY THOMPSON WELLS A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 CAREY THOMPSON WELLS All Rights Reserved ii The Column of Constantine at Constantinople: A Cultural History (330-1453 C.E.) By Carey Thompson Wells This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree in Master of Arts. _______________________ _____________________________ Date Dr. Eric Ivison Thesis Advisor _______________________ _____________________________ Date Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract The Column of Constantine at Constantinople A Cultural History (330-1453 C.E.) By Carey Thompson Wells Advisor: Dr. Eric Ivison This thesis discusses the cultural history of the Column of Constantine at Constantinople, exploring its changing function and meaning from Late Antiquity to the end of the Byzantine era. -

Dyeing Sutton Hoo Nordic Blonde: an Interpretation of Swedish Influences on the East Anglian Gravesite

DYEING SUTTON HOO NORDIC BLONDE: AN INTERPRETATION OF SWEDISH INFLUENCES ON THE EAST ANGLIAN GRAVESITE Casandra Vasu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Committee: Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Charles E. Kanwischer © 2008 Casandra Vasu All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Nearly seventy years have passed since the series of tumuli surrounding Edith Pretty’s estate at Sutton Hoo in Eastern Suffolk, England were first excavated, and the site, particularly the magnificent ship-burial and its associated pieces located in Mound 1, remains enigmatic to archaeologists and historians. Dated to approximately the early seventh century, the Sutton Hoo entombment retains its importance by illuminating a period of English history that straddles both myth and historical documentation. The burial also exists in a multicultural context, an era when Scandinavian influences factored heavily upon society in the British Isles, predominantly in the areas of art, religion and literature. Literary works such as the Old English epic of Beowulf, a tale of a Geatish hero and his Danish and Swedish counterparts, offer insight into the cultural background of the custom of ship-burial and the various accoutrements of Norse warrior society. Beowulf may hold an even more specific affinity with Sutton Hoo, in that a character from the tale, Weohstan, is considered to be an ancestor of the man commemorated in the ship- burial in Mound 1. Weohstan, whose allegiance lay with the Geats, was nonetheless a member of the Wægmunding clan, distant relations to the Swedish Scylfing dynasty. -

INSTITUTE of METALS and METALLURGICAL ABSTRACTS

? . l o O f a G Part 9 The Monthly Journal of the INSTITUTE OF METALS and METALLURGICAL ABSTRACTS CONTENTS ECMNIK Institute News and Announcements Institute of Metals and American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers Personal Notes Local Sections News International Association for Testing Materials 746. The Scientific O rganization of W orks. Autumn Lecture. By P. Chevenard 435 747. Methods for the Examination of Therm al Effects due to O rd er-D iso rd er Trans formations. By C. Sykes and F. W . Jones 469 748. The N atu re of the Solid Solution of A n ti mony in Lead. By N. W . Ageew and I. W. Krotov 493 Appointm ents Vacant and Required 502 Metallurgical Abstracts 337- 384 SEPTEMBER 1936 Copyright Entered at Stationers* Hall From our wide range we are able to supply refractory mat erials of high quality suitable for most industrial purposes. In our various works, which are modern in design and equipment, care is taken in every stage of manufacture to ensure that our products are maintained at a uniformly high standard. For fuller particulars, as, for our Pamphlet, No. 1■ 'B tU E B E L t; SCOTLAND Are you anxious when you test T When you are working to a strict specification, can you witness the tests with a tranquil mind, knowing that you have “ plenty to spare,” or are you conscious that your results are likely to he on the border line? \ our analysis may he right, your foundry technique beyond criticism, and yet your results may he only just passable, whereas your competitor sails through with flying colours. -

Beowulfkvädet

Diktverket Beowulf, som utspelar sig i Danmark och Sverige under 500-talet e. Kr, tillhör världslitteraturen. Det har bevarats på fornengelska i ett manuskript i Eng- land från omkring år 1000 och anses allmänt ha komponerats skriftligt av en kristen Bo Grä Bo fornengelsk diktare som en i huvudsak fiktiv berättelse. När frågan om bakgrunden till detta unika epos här för första gången utsätts för en ingående kritisk granskning ur ett samlat arkeologiskt, historiskt och språkligt perspektiv, framstår denna upp- fattning som ohållbar. Fram träder en ursprunglig muntlig hednisk dikttradition med Beowulfkvädet bakgrund i en faktisk verklighet på Själland och Gotland och i viss mån i Uppland S strax före, under och efter den stora klimatkatastrofen åren 536–550, folkvandrings- lu Den nordiska bakgrunden tidens slut. Beowulfkvädet har av allt att döma överförts som ett enhetligt muntligt N diktverk från östra Sverige till East Anglia omkring år 600 för att sedan under viss d kristen bearbetning traderas i skilda fornengelska dialektområden och till slut för- • evigas på manuskript på västsaxisk dialekt i södra England. Beowulfkvädet Bo Gräslund är professor emeritus i arkeologi vid Uppsala universitet. Bo Gräslund Distribution: eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-6358 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-27-9 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 149 OPIA 64 2 sid2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CXLIX OPIA 64 BO GRÄSLUND Beowulfkvädet Den nordiska bakgrunden UPPSALA 2018 4 Abstract Bo Gräslund, Beowulfkvädet. Den nordiska bakgrunden (Beowulf: The Scandinavian back- ground).